In their highly influential, best-selling book, The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure, Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt identify lies that they claim underlie America’s increasing social and personal dysfunction. Lukianoff is the president of the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE), which in many ways is replacing the ACLU as a leader in the fight to protect free speech. Haidt, a professor of social psychology at NYU, is also the best-selling author of The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided by Politics and Religion.

In The Coddling, Lukianoff and Haidt try to identify the causes of the increase in anxiety, suicidality, and general excessive fragility of American college students, especially since 2013. They conclude that the fragility they identify in iGens (members of the Internet Generation) is due to a number of causes: Helicopter parenting, a tendency to overreact to risks, and a general philosophy of “safetyism.” They show how the various forms of excessive protectionism don’t allow children to develop a sense of their own anti-fragility. But one cause of the problem that they leave out is the effect of pathologizing our children with psychiatric diagnoses, which in turn leads to the attempt to solve life’s problems by administering psychiatric drugs.

Anti-fragility and safetyism

Anti-fragility is developed through the experience of overcoming problems and obstacles. Like peanut allergies that are rare in children who ate peanuts when they were young—and thus relatively rare in China where food is often cooked in peanut oil—a child’s developing psyche needs to be exposed to challenges in order to develop a sense of their own vigor and competence when facing difficulties. Studies show that peanut avoidance in the attempt to prevent allergic reactions has led to a dramatic increase in serious peanut allergies. Just so with the attempt to overprotect children from stress.

Unrealistic safety concerns regarding horrible tragedies such as abduction by child molesters and catastrophic injuries have caused us to make normal, unsupervised childhood play unavailable to the middle and upper-class children who make up the bulk of today’s college students. Terrible tragedies do occur. But when we have media that focuses on such tragedies in a nation of 330 million people, horrific daily stories make it seem that catastrophe lurks around every corner. In fact, abduction, violent crimes, and injuries are much rarer today than when I was growing up and all the “free-range” kids on my block had virtually unlimited, unsupervised, free time. Yet today most people feel that the danger is greater than ever and free-range parenting has led to charges of neglect.

In developing a philosophy that honors strength and passionate living, Friedrich Nietzsche produced the aphorism, “What does not kill me makes me stronger.” Today’s central lie that Lukianoff and Haidt identify as causing the new fragility is the obverse of Nietzsche’s dictum: “What does not kill me makes me weaker.” As with peanut avoidance, rather than letting the psychological immune system develop a vigorous sense of self through the experience of overcoming challenges, children are protected and coddled. This is “preparing the road for the child rather than preparing the child for the road.”

The authors show how increasing fragility is the cause of cancel culture in which ideas that cause discomfort are seen as dangerous and are increasingly disallowed on college campuses. While a culture of respect that protects individuals from direct attack and intentional bullying needs to be created and maintained, the authors see the rash of disinvitation of speakers and the violent obstruction by college students of debate over ideas that may be challenging as symptoms of this excessive fragility.

They identify other sources of the increased vulnerability of recent college students. For example, inordinate hours on screens deprive young people of the innumerable interactions that are needed to develop an understanding of how to navigate through a social world in which conflict and cooperation are always seesawing. Furthermore, unrealistic presentations of self on the internet leave youngsters feeling inadequate and suffering from chronic FOMO.

Documenting these and other factors, Lukianoff and Haidt provide an insightful analysis of the increase of anxiety, depression, and suicidality on college campuses. However, they completely ignore another source of fragility that may account for much of the data they present.

Chemical crutches for the incompetent

We no longer live in a world in which distressing feelings are taken to indicate problems that can be solved through better understanding and changes in social relations. Anxiety and depression are increasingly seen as medical disorders, rather than as challenges to normal living that can be overcome by adaptive changes in understanding and behavior. Thus, there is a growing epidemic of prescribing psychiatric drugs for young people.

“This isn’t a problem you can handle. This isn’t a problem we need to address as a family or community. This is a biological dysfunction that can be ‘fixed’ by adjusting your broken biochemistry.”

Along with the increasing prevalence of “safetyism,” with its message that catastrophic danger is always lying in wait, the medicalized notion that one needs a chemical adjustment in order to cope increases a sense of incompetence and helplessness in the face of increasingly frightening problems.

And the crutches aren’t helping!

Yet, the chemical crutches are not improving things. Despite increasing psychotropic prescriptions, long-term outcomes have been worsening, not getting better. And most of the “improvement” seen after prescribing antidepressants is not due to the medication. Rather improvement that can seem to be due to the drugs, apparently has been mostly due to the placebo effect, ordinary life processes operating over the passage of time, and the selective withdrawal from treatment by those who are not helped and may even suffer from side effects. Yet, we are increasingly medicating more and more young people for depression.

From 2012, when 5% of 12 to 19 years were taking antidepressants to 2019 when 8% of 13 to 19 year-olds were taking antidepressants, there was an approximate 60% increase in antidepressant usage in just seven years. Today, given the increase in anxiety and depression during Covid, the number of young people taking antidepressants is probably well over 10%. That’s between 3.5 and 4 million young people taking antidepressants.

In the mid-1980s when my oldest sons attended Camp Becket, the longest running YMCA camp in the U.S., there surely were some boys taking prescribed drugs of various kinds. It was hard to tell how many. They would go to the infirmary where the nurse would hand out their medications. In the mid-2000s, in contrast, when my youngest sons attended the same camp, at mealtime there were two long tables, each with dozens of folders and a long line of boys waiting to get their meds.

Given the increase in their usage and the 2% increase in suicidality associated with antidepressants, the data indicates that today antidepressant usage induces suicidality in about 80,000 young people nationwide.

Lukianoff and Haidt noted the upsurge in the number of college students accessing mental health services for depression and anxiety. They cited an article in Psychology Today, which noted that:

Nationally, 22 percent of collegians now seek therapy or counseling each year, reports Daniel Eisenberg, an economist at the University of Michigan whose Healthy Minds Study annually samples 160,000 students around the country. The number of those in counseling varies from campus to campus depending on its culture—10 percent at some large schools, nearly 50 percent at some small, private ones. The figure has been steadily growing for two decades and shows no signs of slowing. … [O]ne in three students now starts college with a prior diagnosis of mental disorder. Academic or social stress, late-night cram sessions, any disruption of routine in the looser-than-home campus environment can shatter their stability. … Eisenberg’s Healthy Minds Study indicates that 19 percent of all college students regularly take psychotropic meds. … Distress on campus takes a variety of forms, but far and away the leading concern in 2015 is anxiety—54 percent of all college students report feeling overwhelming anxiety, up from 46.4 percent in 2010, according to the latest semiannual survey conducted by the American College Health Association. That wasn’t always the case.

And we can be pretty sure that among those young folks seen at college counseling centers, the percentage taking antidepressants is much higher than 10%.

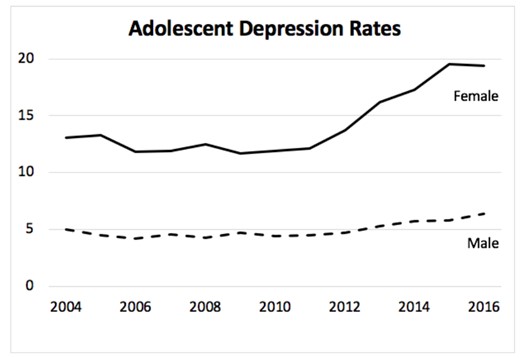

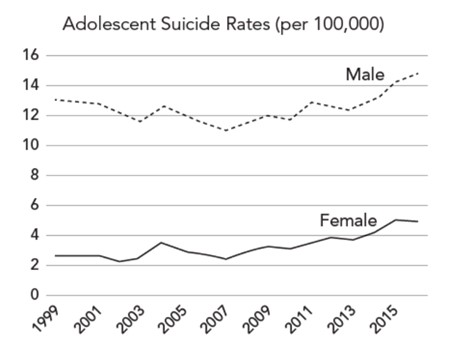

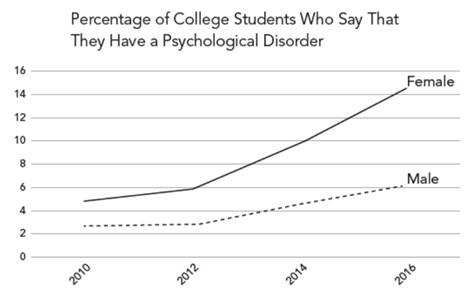

Lukianoff and Haidt’s concerns are summarized in three charts they present. Here they are:

Coddling and medicating: A synergistic runaway train

The Coddling of the American Mind is a deeply insightful and important book. Anyone who wishes to understand the cultural dysfunction afflicting America today will find this a worthwhile read.

Yet, it seems pretty clear that the fragility and dysfunction they are trying to explain could be induced by the psychiatric mindset that is conducive to feelings of helplessness, a lack of a sense of agency, and the damage induced by the drugs themselves. Lukianoff and Haidt are trying to explain depression and increased suicidality during a time period in which the documented 2% increase in suicidality caused by antidepressants could account for much if not most of the negative trend they are trying to explain.

There may be a synergistic interaction between the causes identified by Lukianoff and Haidt and the negative impact of psychotropic medication. The increased fragility, anxiety, and depression they are trying to explain apparently cause an increase in psychotropic interventions. And the increase in the use of psychotropic medication could account for the increase in learned helplessness and suicidality, which in turn causes an increase in the reliance on medication, which in turn…

As both a physician and a patient, this really resonates with me. Not only do I believe that medication alone is too often thought to be enough, but I am constantly researching my patients’ medications only to find that several of them counteract each other, or cause serious interactions with other drugs about which they didn’t know. From my own experience, I can tell you that addressing mental conditions from all sides (meds, counseling, sleep, treating other related medical conditions) is way more likely to be effective. We need to spend time working on re-framing our thoughts and responses to stress, especially in the wake of the pandemic. When it comes to feeling safe, the phrase “you can’t miss what you never had” certainly comes into play, especially when “fragility” is a result of the support and kindness you relied on gets pulled away from you without warning. Thank you for this piece.

Report comment

“But one cause of the problem that they leave out is the effect of pathologizing our children with psychiatric diagnoses, which in turn leads to the attempt to solve life’s problems by administering psychiatric drugs.”

Thank you for identifying the source of the problem. And the fact that the authors themselves did not mention this speaks to how blind even the “experts” are, and more troubling, how insidious psychiatrization really is.

Imo, society’s collective consciousness has been and continues to be contaminated by the media’s fascination with psychiatry’s lop-sided logic and now proven junk science, the result being no one need see a doctor to be inundated with psychiatry’s medicalized psychobabble as all you need to do is turn on the tv or get on the internet. So, it’s no wonder that adolescents’ developing sense of self osmotically absorbs the media’s inappropriate ideas and psych-lingo, the unfortunate consequence being many now have a hard time seeing their feelings as essentially normal and healthy. But that’s what happens when you label feelings as “disorders” and normalize drugging.

Report comment

This is an insightful and significant critique of Lukianoff and Haidt’s explanation for behavior trends in the current college-age generation. A relative of mine who worked as a counselor at an upper-middle-class summer camp recounted that fully 40% of the campers were on some kind of medication. Surely psychotropic dosing during development and influential psychological paradigms are factors that need to be addressed in any working theory of youth behavior. As both authors are known for their empiricism and openness to debate, I hope this article comes to their attention and that they test these ideas in future research.

Report comment

I would add that the presence of psychiatric drugs not only can do damage itself, but it also diverts young people (and older people) from other approaches that have been successful over time, both formally and informally. It may be the lack of developing support networks as much as drug side effects that are helping cause the deterioration of youth “mental health” today.

Report comment

“As both authors are known for their empiricism and openness to debate, I hope this article comes to their attention and that they test these ideas in future research.”

Somehow people who write entire books on the deterioration of teenagers’ “mental health” WITHOUT including the undeniable influence of psychiatry’s medical model paradigm AND the pharmaceutical industry’s increasingly proliferative advertising don’t strike me as particularly open-minded, to say nothing of being “empirical”. So it looks to me that these “researchers” don’t know how to do “research”. But more likely they’re afraid of debate. And I didn’t need to wait for some “researcher’s” “research” to reach THAT conclusion.

Report comment

Thank you, Dan, for pointing out the elephant in the room. (It’s the drugs, stupid.)

“Helicopter parenting, a tendency to overreact to risks, and a general philosophy of ‘safetyism.'” Always blaming the moms, instead of the scientific fraud based psycho pharmaceutical industries, themselves.

Report comment

I was drawn to the word “medicalization”. I am a fan of the brain inflammation theory, a medical understanding of the way our modern diet destroys the gut’s ability to make what neurochemicals in the brain need. I am not a doctor so excuse me if I summarize it ineptly. Anyway, brain inflammation in the masses due to toxic foods like sugar and carbs might account for some of the uptick on the graph of increasing psychological disability. The study of the way the gut is vital for brain homeostasis is a “medical” study. I think the word “medical” is not the bogeyman. Bad treatments come from bad behaviour at top levels. Bad behaviour that sanctions bad treatment is caused by bullying. And that can occur in any system. Getting rid of a system like the “medical” system would deprive people like me from accessing latest scientific medical research about the way our biology and brain is confounded by poisonous diets.

Overall though I do like very much your article. I think it is grim that kids line up to get substances that prop them up.

There is a book called “Brain Energy” by Dr Palmer, a trailblazing Harvard professor and psychiatrist who has extensively studied the “medical” disaster caused by brain inflammation, and a metabolic disruption, that when treated by corrective nutrition resolves severe mental problems in many.

Humans do not like to think that profound psychological distress might be caused by a chocolate muffin.

Yet if you take dogs and cats to a vet when those betray signs of odd behaviour the first thing the vet asks is what the animal has been fed on. Humans are animals.

Report comment

Subliminal seduction via pharmaceutical advertising influences mindsets more than anything because it’s subliminal. And mindsets subliminally influenced are especially hard to identify and dislodge. Any psychologist (or PR person for that matter) worth his/her salt will tell you this, though this doesn’t necessarily mean that psychologists are aware of how much they’ve been subliminally seduced by their own biased educations. And subliminal messages work well because these don’t use “empirical data” to sway people, which makes people think they’ve arrived at conclusions all on their own. And that’s how advertising shapes the world we live in.

Report comment

I think it’s helpful to ask “Why?” until a root cause is found. Regardless of how many people are on drugs for conditions like depression and anxiety, the question is Why have the incidence rates of virtually every mental health condition been steadily increasing for decades and decades? One could perhaps attempt to argue that it all started with over-diagnosis, at which point we over-prescribed and exacerbated the problem even more. But this doesn’t do it for me. The totality of the evidence, from my perspective, points squarely at developmental trauma – both overt and covert.

(At the risk of blatant self-promotion, my article on MIA from a few months ago goes into more depth on this.)

Report comment

“The totality of the evidence, from my perspective, points squarely at developmental trauma – both overt and covert.”

I agree. However, the recent avalanche of arguably erroneous psychiatric assumptions leads people to erroneously believe that their uncomfortable reactions to life itself are the result of an organic illness/disorder/disease within themselves that unquestionably requires consuming potentially harmful psychotropic pharmaceuticals the rest of their lives, which is not only erroneous, but another trauma, in and of itself.

Report comment

Correction “undeniably erroneous”, not “arguably erroneous” —

Report comment

And regular medical doctors (non-psychiatric) have unfortunately acquired the careless habit of not doing what they’re trained to do, which is SEARCH FOR POSSIBLE PHYSICAL CAUSES that have NOTHING TO DO with psychiatry’s phantom “chemical imbalances”.

Report comment

You are so right. My post-psychiatry life has endured because I’ve grown more willing to advance myself by taking risks. Psychiatry causes so much destruction to people before they finally escape from it, that virtually ANY ordinary choice they make entails and excess of risk. A void of intuition, confidence, and optimism is created in a life when psychiatry consumes a person’s energy and time over a period of years or decades. Positive qualities such as those are produced by a variety of experiences, which typically can’t accommodate psychiatry’s dogma and demands. Without enough space for personal growth, a psychiatric “patient” becomes mired in a life of exponentially increasing dysfunction that is used as further “evidence” of their “mental illness”, not as evidence of unsafe “caregiving” relationships. It’s a vicious cycle that ends in death, unless the Mad person finally says, “NO!”.

Report comment

The ‘medicalization’ of the American mind? Why not call it the ‘psychiatrization’ of the American mind? But both mean essentially the same thing: framing and naming normal (though sometimes extreme) reactions to difficult or even traumatic experiences as “disorders” or “illness”. And this has undeniably succeeded in convincing people (especially young ones) that they’re incapable of coping without the aid of prescriptions for any number of psychotropic drugs. And this conveniently eliminates considering the possibility of earlier developmental trauma that nowadays includes the overwhelming influence of social media.

And for those who have a habit of saying “correlation is not causation”, I would suggest that for things “psychological”, framing is everything. So perhaps they should entertain the novel idea that correlation often leads to causation, and from there take the flying leap of faith that perhaps traditional methods of scientific inquiry may not be ideally suited to the eternally fuzzy world of “psychology”.

Report comment

J says: “Without enough space for personal growth, a “psychiatric” patient becomes mired in a life of exponentially increasing dysfunction that is used as further “evidence” of their “mental illness”, not as evidence of unsafe “caregiving” relationships.”

And THAT describes “psychiatric treatment” in a nutshell!!!

Report comment