Psychiatrist Richard A. Friedman’s attempt, in his New York Times opinion piece (“Teenagers, Medication and Suicide,” August 3, 2015), to minimize the dangers of antidepressant drugs in causing suicidal thoughts and behavior is wrong on the facts. Friedman is wrong, even according to Friedman, when his argument and numbers are examined. Just consider two of his claims:

“What the public and some in the medical community … perhaps still don’t know — is that the risk of antidepressant treatment is minuscule: In the F.D.A. meta-analysis of some 372 clinical trials involving nearly 100,000 subjects, the rate of suicidal thinking and behavior was 4 percent in people taking antidepressants, compared with 2 percent in people taking a placebo.”

“One study found that a 1 percent increase in adolescent use of antidepressants was associated with a decrease of 0.23 suicides per 100,000 adolescents per year. (Of course, correlation cannot prove causality; other factors, like reduced rates of alcohol and drug use and more stringent gun safety regulations during this period, may have played a role, too.)”

A moment’s reflection makes these statements puzzling, at best.

Antidepressants Cause Suicidal Feeling, Thinking, and Behavior

First, consider his claim that the risk of antidepressant treatment is minuscule. As Friedman notes, the FDA meta-analysis of clinical trials of nearly 100,000 subjects established the fact that antidepressants double the rate of suicidal thinking and behavior from 2 percent to 4 percent. This is the unequivocal finding from “gold standard” research, that is clinical studies that use randomized control trials (RCT) to establish causal relationships. In RCT clinical trials, subjects are randomly assigned to either the drug group or a placebo. In this way, two groups that differ only on whether or not they received the drug can be compared to evaluate the drug’s true effect.

It is based on these RCT studies that the FDA decided to issue black-box warnings that antidepressants increase suicidal feeling, thinking, and behavior in adolescents and young adults. It is based on the same studies that Friedman makes his claim that there is only a 2 percent increase in suicidality due to antidepressants. While an increased risk of suicidal thinking and behavior of just 2 percent may seem small, we need to look at what this means in real lives.

In Adolescents

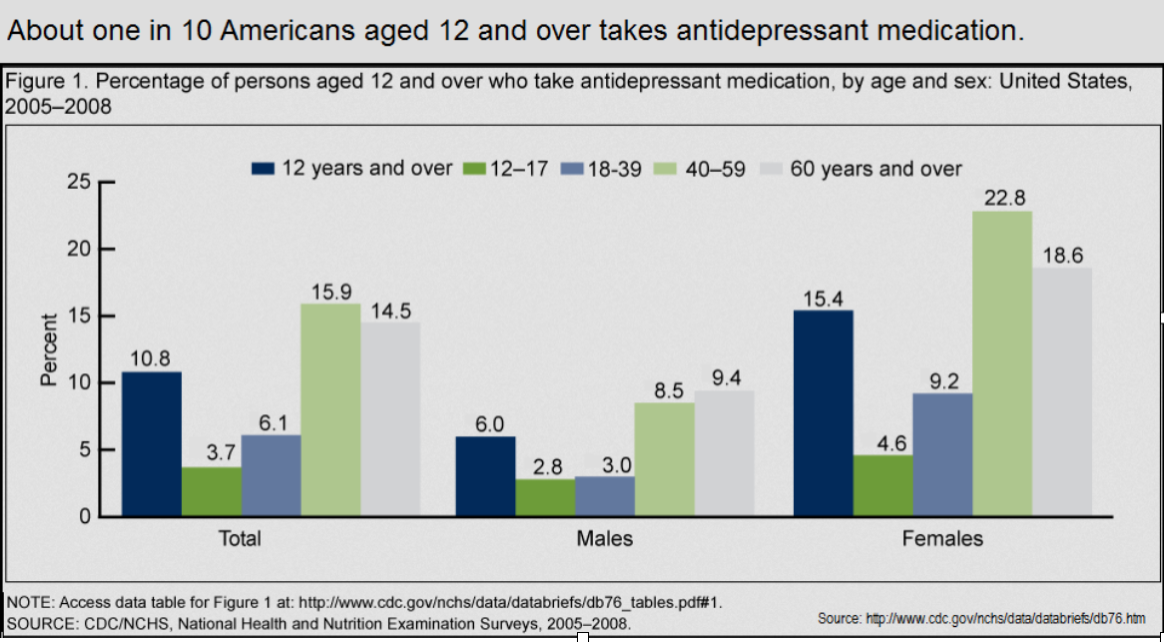

So let’s do the math. 12 to 19-year-olds make up just under 11% of the total U.S. population of over 319 million. Since more than five percent of this group of 34 million young people are taking antidepressants,1 and since Friedman acknowledges a related 2 percent increase in suicidal thinking and behavior, this means that about 34,000 adolescents experience antidepressant induced suicidality. Is that a minuscule risk?

In Adults

And the numbers are much worse for older people who, on average, use antidepressants at well over twice the rate of adolescents. And though the effect in this older group may not be as marked, these drugs are known to increase suicidality as well as violent acts in some adults without a prior history of inner or outer directed violent behavior. Since there are 236 million Americans age 20 or older, if over 10% are taking antidepressants, that makes well over 24 million users in the adult group. At a 2 percent rate of antidepressant caused suicidality, we would have to add an additional 480,000 people to the group afflicted with this “side effect,” bringing our total number to over ½ million. More than half a million people afflicted with suicidal thinking and behavior they wouldn’t otherwise experience is simply not a minuscule risk.

Now You See it; Now You Don’t

Next, consider the logical sleight of hand Friedman engages in. Davids Copperfield and Blaine could build entire careers on one magic trick as good as Friedman’s. In case you don’t know, one of the techniques of master magicians is misdirection: While you’re looking over there, the switch takes place over here. So let’s look at Friedman’s masterful legerdemain.

First, he acknowledges the well established fact that antidepressants increase suicidal thinking and behavior. Then, with a misdirecting flourish that would make any prestidigitator proud, Friedman makes the increased suicidality vanish only to be replaced by a beautiful but scantily clad statistic: Antidepressants were found in “one study” to be associated with a decrease in suicides. To his credit, Friedman follows this with an acknowledgment of the disclaimer found in that study: Correlation may not indicate causality and there were a number of other factors that could have accounted for the finding of decreased suicides. But by this point, many if not most readers may have been distracted from the fact that Friedman is now suggesting the exact opposite of what he had earlier conceded.

You see you can’t have your cake and eat it, too. Either the robust finding of an increased risk of suicidality associated with antidepressants that has been demonstrated by numerous gold standard, RCT studies is valid; or antidepressants decrease suicidality, as Friedman suggests by citing one correlational finding that he acknowledges doesn’t establish causality. Which is it? It can’t be both. When we have a finding based on abundant evidence using the gold standard — something that took many years to establish — why would we abandon that finding? Is there a hidden agenda motivating what appears to be intentional misdirection?

The Dangerous Implications of Biased Pseudo-science

On a deadly serious note, Friedman calls for the removal of the black-box warnings that he laments led to a 31% decrease in the use of antidepressants by adolescents (though he sees some good news in the gradual reversal of this trend). So, let’s do the math again. As noted above, according to the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics 5% of American teenagers (12- to 19-year-olds) use antidepressants. This translates into approximately 1.7 million teenage users. If that number were decreased by 31%, that would mean that 527,000 — over ½ million — teenagers didn’t receive these drugs and over ten thousand cases (2% of 527,000) of increased suicidality were prevented by the black-box warnings that Friedman wants to see removed.

But it’s a Risk Worth Taking

All medications incur some degree of risk. There is no free lunch. If you employ a drug that is powerful enough to have a real impact and improve a situation, its very power also makes it likely that, for some people, there will be a degree of harm. The risk of harm must then be weighed against the severity of the illness and the drug’s potential for ameliorating suffering. Is the likelihood of benefit worth taking the risk of the potential harm?

Friedman is clearly suggesting that with antidepressants there are benefits that outweigh the risks. However, in the case of suicidality, the gold standard data indicates there is no overall benefit; on average, there is only harm. In the groups that received the antidepressants, suicidality was doubled. If we want to keep suicidal thinking and behavior to an absolute minimum, evidence-based medical practice would not include the routine administration of these drugs to adolescents and young adults. Again, this is precisely the reason the FDA decided on the black-box warnings in the first place.

Beyond Suicide

But what if we look beyond suicide? Today, we are bombarded with drug ads. During each such ad, we hear warning after warning about a slew of side effects. So it is now commonplace knowledge that we take drugs aimed at alleviating suffering even if there is a risk of harm, including death. What about the suffering from depression that would be diminished by antidepressants? We have to take that into the risk-benefit analysis. Well here’s where Friedman’s recommendation becomes even more troubling.

“Depression is, on the whole, one of the psychiatric conditions with the best prognosis for eventual recovery, with or without treatment. Most depressions are self limited,” Jonathan Cole [Director of the Psychopharmacology Service Center at NIMH] wrote in 1964. … Indeed, as Dean Schuyler, head of the depression section at the NIMH, explained in a 1974 book … most depressive episodes “will run their course and terminate with virtually complete recovery without specific intervention.”2

Is it ethical to give drugs that will induce suicidal thinking and behavior to a group of young people suffering from a self-limited bout of unhappiness?

Furthermore, the evidence strongly indicates that these drugs provide virtually no benefit for those suffering from mild to moderate depression.3,4 When there is a risk of significant harm and no benefit, we should be trying to avoid such prescribing; young folks in this group will get better on their own and antidepressants provide no discernible benefit over placebo. In any ethical cost-benefit analysis, there is no justification for medicating such youngsters.

What about the severely depressed? There is some indication that the severely depressed may receive some benefit from antidepressants. However, the black-box warning that Friedman would have us remove does not prevent the prescription of these drugs to the severely depressed. The warning is worded precisely to make doctors think twice before automatically responding to signs of unhappiness with a prescription pad. Curtailing reflexive prescribing for millions of young people and reserving these drugs for only those suffering from severe depression would seem to be ethically necessary.

The New York Times

Finally, I must say I am troubled by the fact that The Times continues to publish opinion pieces based on a perspective heavily promoted by commercial interests without providing critical, alternative viewpoints. And this despite the fact that the editorial board at The Times is well aware of how commercial interests have come to dominate medicine:

“New evidence keeps emerging that the medical profession has sold its soul in exchange for what can only be described as bribes from the manufacturers of drugs . . . It is long past time for leading medical institutions and professional societies to adopt stronger ground rules to control the noxious influence of industry money on what doctors prescribe for their patients.” (The New York Times editorial: “Seducing the Medical Profession,” February 2, 2006)

Unfortunately, The Times isn’t able to use this awareness to consider publishing opinion pieces that challenge organized psychiatry.

Not only did they publish Friedman’s dangerous call for removing the protective black-box warning, for some reason, reader comments on Friedman’s piece were not enabled. Do they recognize the fact that Friedman’s view might call forth an outpouring of protest? Have they been convinced by organized psychiatry and Big Pharma that such an onslaught would come from crazy, psychiatric survivors and conspiracy theorists?

Well General Dwight Eisenhower was certainly no loose cannon or conspiracy theorist. In his parting words as president, he warned us of the corrupting power of huge economic interests. Today, the pharmaceutical industry is the third largest in the world (after energy and the military). When you ally it with medicine and health care, it becomes the largest commercial complex of all. So to paraphrase President Eisenhower:

We must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the [psychopharmaceutical]-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist. We must never let the weight of this combination endanger our liberties or democratic processes. We should take nothing for granted. Only an alert and knowledgeable citizenry can compel the proper meshing of the huge [medical and pharmaceutical] machinery … so that [the general well being may be promoted].5

How can a knowledgeable citizenry do that if one of the few remaining, quality sources of news and information cannot free itself from that very unwarranted influence?

* * * * *

References:

1. “The Medication Generation,” by Katherine Sharpe, The Wall Street Journal, June 29, 2012, stated that the “National Center for Health Statistics says that 5% of American 12- to 19-year-olds use antidepressants.” Since antidepressant usage has been increasing since 2012, the number today would be over 5%.

2. Robert Whitaker (2010). Anatomy of an Epidemic: Magic Bullets, Psychiatric Drugs, and the Astonishing Rise of Mental Illness in America, Crown, pp. 152-153.

3. Irving Kirsch (2010). The Emperor’s New Drugs: Exploding the Antidepressant Myth, Basic Books.

4. Robert Whitaker and Lisa Cosgrove (2015). Psychiatry Under The Influence: Institutional Corruption, Social Injury, and Prescriptions for Reform, Palgrave Macmillan.

5. From the final public speech of Dwight D. Eisenhower as President of the United States, delivered in a television broadcast on January 17, 1961. Only the bracketed words have been added.

11 % of the adult population of the USA is said to be taking antidepressants at the present juncture in time. I find such statistics less surprising than alarming. Unhappiness, apparently, is big business. You give 5 % as the percentage of school children taking these drugs. That is another no less alarming statistic. We’re talking children after all. What would removing black box labels achieve beside raising these percentages. Pulleeze, we don’t need this nonsense. Big Pharma is booming as is. Thank you for this post. The New York Times should tell this bozo to peddle his pills, and free of charge by the way, elsewhere. People are getting literally sick from all the drugs psychiatry is pushing down their throats. Less is so much more when it comes to drugs and health.

Report comment

I guess we should all write some scathing letters to the editor for publishing this bs. Btw, what are the conflicts of interest of this guy?

Report comment

I read Friedman’s NYT’s opinion piece when it was first published and, like you, was disturbed by it. It was thus a pleasure to read your excellent critique of the piece. I just want to emphasize one point. I do not feel that the NYT provides quality news and information, at least not in its reporting of health related studies (including psychiatric studies). The articles on these studies often read like press releases for the study authors. They exaggerate the benefits of treatments and drugs by reporting relative risk statistics instead of more meaningful measurements like number needed to treat to obtain the desired results. The reporters do not appear to have enough statistical knowledge to adequately question the study authors. And they often don’t report conflicts of interest. So Friedman’s op ed fits in very well with the unsatisfactory approach the NYT takes to its health reporting in general.

Report comment

I find NYT’s health reporting to be the least bad of the mainstream media. They recently ran a withdrawal diary of a woman struggling to free herself from psych drugs; a few years ago there was Marcia Angell’s report on the state of psychiatry that actually discussed the work of Robert Whitaker. A while back they ran a column by T. Luhrmann that enraged Dr. Lieberman. Compare the NYT to the Wall Street Journal which regularly trots out Fuller “Drug ‘Em Torrey” as its resident expert on mental health and proper treatment. Given the low bar set by consistently subpar mental health reporting across the board, I believe the NYT shines, comparatively speaking, of course.

Report comment

We also have to remember that in almost all RTCs, actively suicidal people are removed prior to the investigation beginning. So we’re seeing 4% increases in suicidal thinking in people who WERE NOT THINKING OF SUICIDE BEFORE TAKING THE DRUGS!!! How this doesn’t merit a warning of the most serious kind is beyond my comprehension.

— Steve

Report comment

If anything, black-box warnings should be strengthened to inform patients, parents and prescribing doctors that antidepressants may trigger mood swings or rage attacks that will be mischaracterized as juvenile bipolar illness, to be treated with neurotoxic cocktails that will destroy a young life in slow motion. These drugs should be banned for minors outright, but that is not likely to happen in the current state of affairs.

Report comment

Doing the same thing over and over and expecting a different result is a definition of insanity for some. So how do we call a society which insists on prescribing people more and more “anti-depressants” when it’s clear that they do not do anything against the “depression epidemic”? when do we start treating human emotions as normal responses to their lives instead of pathology?

Report comment

Your piece on anti-depressants is very enlightening and thought-provoking. There are also many points of truth. In light of this, I would like to mention an article I read today in this month’s AARP magazine. The author of the article speaks of her need for antidepressants. She tried several including Prozac and is now on Lexapro. According to her report; she states that she could not function without the anti-depressants. She had gone off of them and was alright for awhile working and raising her family. She then had trouble again and went back on the anti-depressants. She, according to the article, realizes what has been “drummed” into the general public during the past twenty or so years; many people need anti-depressants like many people are taking insulin. She does cite contact with personnel at NAMI. First, I have a question does AARP take money from BigPharma like many other non-profit organizations such as NAMI and others. Second, don’t you think it is rather spurious and slightly skewed from the point of AARP to print only one side of the story; especially when they report to a very vulnerable population medically; the over 50 and the over 65 and above age group. It is particularly suspect when reporting the medically vulnerable of the over 70 and age 75 age group. The author began her “journey” with anti-depressants at about age 26. Many of the readers would not begin their prescription, possibly until at least after age 50. The other thing that concerned about that the article was that the side effects were rather brushed under the rug and the side effects of an “aging” population is well documented and exceedingly harmful. I am very concerned. I am beginning to believe that AARP no longer has the best interests of the over 50 age group at heart and their concepts that there are “second chances” after age 50 are very very true; I don’t believe that one in the over 50 age group will find their second chance with AARP. It is all a sham to keep them in business. Sound familiar? Thank you.

Report comment

I find this interesting especially in light of the fact that prescribing anti-psychotics for older adults is being brought to the forefront as a deadly action. Then there is the over prescribing that is cradle to grave. Big pharma shoring up it’s bottom line.

If it walks, talks and acts like a pharmaceutical ad it is. These charlatans are having to be a bit more creative in their direct marketing gimmicks as more people catch on.

Report comment

Looks like (yawn) another intellectual discussion of whether and how extensively children should be dehumanized and neurologically impaired.

Report comment

Oldhead; although with children, it is very alarming; since there minds and bodies are still growing and they are so vulnerable and innocent. It is like an abortion of the already born. But, this dehumanization and neurological impairment includes not only children and teenagers; but adults from young adults all the way to the elderly adult. And, who can we really verify that we actually do stop growing at age 18 or 25 or 30 years of age; as it seems the more we think we though about the body and mind of the human being, the less we know. And it is not only the neurological impairment; but impairment of the entire physical body, too. And, it has become so far reaching that it not only includes the fake science of psychiatry; but traditional medical science with all its specialties and sub-specialties that we have trusted and depended on all these many years and even centuries. Next to the threats from terrorism; such as ISIS and other groups; the “whole health care industry” is a definite and decided threat to our national security. This is a shame; because there really some good doctors and nurses, etc. but they are getting more and more lost or disaffected by the system. I wonder; could the “whole health care system” which not only includes the traditional delivery arenas; but of course, also, BigPharma, insurance, even Medicare and Medicaid, etc might be considered another form of domestic terrorism. It is nor coincendence that disability and death rates have risen from the iatragenic injury across all area. Please excuse my spelling. I was an excellent speller before the toxic, dehumanizing, addictive, drugs and other such stuff was coerced and forced on me like I was some sort of prisoner of war. Is that what we are dong to our most vulnerable; our children; making them prisoners of war? Thank you

Report comment

You seem to miss my point entirely, which is that entirely too much verbiage is wasted analyzing the obvious, and evaluating moral issues in pseudo-scientific terms.

Report comment

The issues that arise are our re-education regarding consciousness. The model of a segregative and conflicted self has been deeply learned over millennia. Friedman exemplifies the attempt to deceive and distort or deny true communication in asserting a personal private agenda of exercising power over others whilst posing as a credible scientist or public service. Now he may in some degree believe that power is the bottom line reality and that truth is a vanity phrase because power dictates the mainstream narrative, and he may believe that deceits are necessary evils in the larger institutional role of human and scientific progress against even worse evils it holds back – regardless any of its own. And he may believe he is a respectable and accomplished scientist. And he may cling to such beliefs in reinforcement with others who share their purpose because they protect him and them from what is feared enough to determine he makes the choices that he does.

De-constructing false arguments is time consuming but sometimes necessary and helpful. But to me I only have to begin reading Friedman to recognize a coercive agenda and hence do not regard it AS communication but propaganda. The corruption of science is within the blindspot of scientists’s beliefs about science and themselves – as is every corruption operating within self-righteousness and self-specialness.

Report comment

If I try to make Richard Friedman’s argument for him, it would go like this. Consider the teenagers who are severely depressed and seriously suicidal. Antidepressants are known to help at least severely depressed patients, so perhaps antidepressants will reduce the chance of suicide in this particular subset of the depressed teenage population. In a limiting case, suppose that there are teenagers who are definitely intending to commit suicide. Shouldn’t such teenagers try antidepressants?

I think that’s a defensible view, but I don’t see how any such argument (or anything else) can justify removing a warning of a known true side-effect. It seems to me that patients and MDs are entitled to be informed, ethically speaking, no matter what. I don’t see how anything can justify hiding this information from MDs and patients.

What I personally find the most disturbing about Friedman’s article is the implicit subliminal messages. Someone reading the article is likely to get a strong impression that the main risks of antidepressants are a minor risk of suicidal thoughts (for, otherwise, he would surely mention other risks) and a strong impression that antidepressants are the most effective treatment for depression (for, otherwise, surely Friedman would be insisting that teenagers should get more therapy, exercise, meditation, etc.).

– Saul

Report comment