Last year I attended a prestigious international psychiatric conference at PGI Chandigarh, India, a medical school of considerable reputation in South Asia. The theme of the conference was public mental health. It was held over three whole days; 900 people from across the world had registered to attend, both face to face and virtually!

It was a star-studded event, with prominent figures from world psychiatry in attendance. This included Norman Sartorius (former director of the World Health Organization’s Division of Mental Health and former president of the World Psychiatric Association and of the European Psychiatric Association), Helen Herman (former president of the World Psychiatric Association), and Jonathan Campion (affiliated with UK’s NHS and advisor to the WHO). Elites of the global mental health movement such as Vikram Patel were also present and so were eminent Indian psychiatrists, especially from public sector teaching hospitals. Some, such as Patel, gave their talks virtually.

Having spent 10 years in the United States, I was well aware of the crises plaguing this discipline. I had become accustomed to news of the rampant abuses by the psy-disciplines (psychiatry, psychology, counseling), shady research practices, ineffective treatments and their adverse effects, scandals related to corruption and incompetence, unrelenting and misguided hubris, savage attacks from inside experts, and the discipline’s flailing excuses in the face of these embarrassments. I wasn’t sure what to expect from Indian psychiatry but I was not hopeful.

The reason I am writing about this conference—and why it’s relevant for a global audience—is because one of the leading trends in the psy-disciplines is the export of their knowledge and interventions to the rest of the world, especially low- and middle-income countries, alternatively known as the Global South. This is known as the Movement for Global Mental Health. When it emerged in early 2000s, it was brutally critiqued for its universalist assumptions and its tone-deafness to local realities. In response, the movement has taken a reflexive turn where it claims to have reformed itself. This conference allowed me to put those claims to the test. It also helped me observe the various iterations of psychiatry, how it changes shape and form, and how it is changed by indigenous knowledge.

In the end, I was both pleasantly surprised and eventually disappointed.

A Glimmer of Hope: Pharma on the Sidelines

As I entered the crowded makeshift courtyard to pick up my conference pass, I noticed multiple displays pointing to industry advertisements for numerous psychopharmaceuticals. I felt a tingle of excitement, a sense of a-ha! of a person who has caught red-handed someone they expected of grave wrongdoing. Stories of garish industry advertising and shady entertainment provided at early American Psychiatric Association (APA) conferences started running through my mind. Was I going to find attractive young women delicately touching the elbows of older eminent psychiatrists?

Thankfully, this was different, very different.

The pharmaceutical industry in this conference was treated like a creepy rich uncle who you must invite to the family reunion but then also strategically ignore. Unlike what I had read about the savviness of pharmaceutical representatives, reps here were only mildly interested in selling their products and knew even less about them. One rep told me “This is just the same drug with a different name. I don’t know why.”

The attendees of the conference seemed equally disinterested in pharma booths; however, I noticed that people frequenting these booths tended to be younger. Most hilariously, the pharma sessions were so sparsely attended that it almost made me feel pity for the presenters. At one session, I was the only real audience and the six other people in the room were all presenting a new medical device to each other.

Industry sessions were delegated to a separate building and took place in small, dingy rooms which were comically difficult to find. The session on an ADHD drug was on the wrong floor than the one specified in the conference pamphlet! Here is the kicker—or, as in Hindi we say, sone pe suhaaga—these sessions were scheduled during the lunch hour far away from the building where lunch was served.

In many medical conferences in the United States, industry sponsors fancy lunches and schedule their own sessions in the same hall at the same time ensuring maximum attendance. I feel that PGI’s status as a reputable public institute makes this distrust towards the industry understandable. Public sector doctors in India mostly prescribe drugs that are available in government clinics, making luring them with goodies rather difficult. Also, traditionally, there has been a suspicion of privatized healthcare (although this is rapidly changing in a neoliberal India) and associations with industry are frowned upon rather than seen as a symbol of status and repute.

Apart from sidelining the industry, the conference had other significant positive attributes. The public-sector Indian psychiatrists, who tended to be older, were deeply critical of overdiagnoses, overprescription, and polypharmacy, and instead spoke consistently about honoring a person’s story and not just seeing them as a set of symptoms.

“Look at the people—what diagnoses and what antidepressant—that’s all we do” was one such refrain. Another was: “Symptoms are a smoke-screen; look beyond the symptoms at the person.”

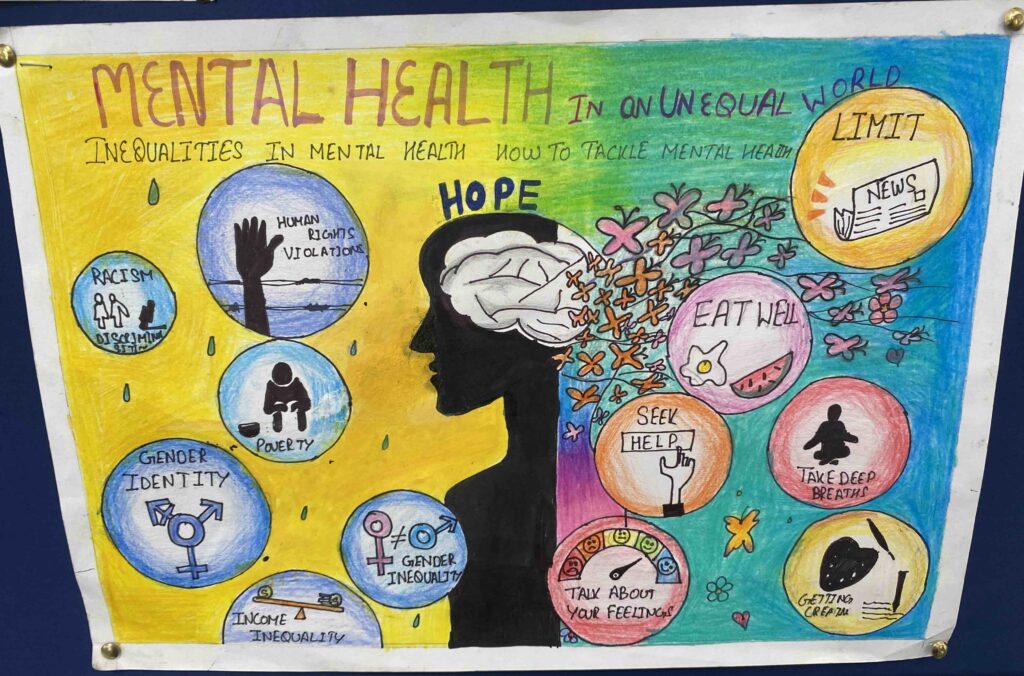

These speakers were cognizant of structural determinants of mental distress such as poverty, discrimination, and gender-based violence. A few openly and casually admitted that psychiatric diagnoses are simply provisional categories and “have no objective existence.” This claim was accepted without resistance among the rest of the panelists. I was left impressed, surprised, and mildly proud of my people and the work they do.

Additionally, the conference highlighted the work of numerous non-psychiatric, non-mainstream organizations that do trauma-informed work, provide financial and psychological help to the marginalized, mobilize legal resources for the victimized (mentally unstable people on death row), and so on. They discussed how psychiatric ignorance of comorbid physical issues often leads to misdiagnoses; for example, diagnosing children who have hearing or vision problems with dyslexia or ADHD.

One presenter openly addressed psychiatry’s role in torturing prisoners during Bush-era administration, centering a human rights approach towards patients. Another asserted that a person’s right to consent, dignity, and liberty trumps their right to treatment. A prominent female Indian psychiatrist spoke of medicalization of women’s problems, and how men often use psychiatric medication to quell to women’s legitimate responses to mistreatment and abuse.

Many South Asian psychiatrists spoke about the importance of good diet, healthy lifestyle, sleep, and exercise as central to mental health. “Everyone is into diagnoses and causes and not into helping and solving,” one speaker said. NGOs discussed systemic issues that cause psychological distress, such as inability to access government assistance for those who don’t have government IDs which leads to increased mental duress. Others noted the importance of building interventions based on what the community itself considers important and beneficial, not some outside experts.

After the first day, I was exhilarated. This was a place where structural determinants were featured front and center, where industry was treated like it was a dirty rag to be kept outside the house, and where overdiagnoses and polypharmacy were deeply problematized—all in a mainstream psychiatric conference! One wouldn’t be wrong in calling me giddy!

“It’s Complicated”: Empty Promises and Failed Agendas

By the second day, I started feeling something was amiss. Among the rhetoric on structural determinants (poverty, violence, exploitation, etc.) and how we must make care accessible to more people, no one clearly stated what this “care” was that merited desperate escalation. This is the central premise of the Movement for Global Mental Health—that limited and middle income countries are in abject need of psychiatric care but have a personnel shortage—a treatment gap. What was the treatment?

When I decided to ask this question individually to Jonathan Campion, he mumbled something about antidepressants, and how things are “complicated.” When I pushed about which “amazing treatments” needed scaling up and what about the role of culture-specific issues, I received a response that had multiple buzz-words but was essentially empty—how “antidepressants work right now but therapy takes time”, and how we need to improve primary care. Given that prominent experts have criticized both psychiatric screening and diagnoses by primary care physicians for leading to diagnostic inflation, this claim was a red flag.

The absurdity of fixing farmer suicides in India, caused by multiple systemic issues, with problematic antidepressants was probably not lost on them, which is why there was really no deep discussion on which treatments should be made affordable. This incited me to ask more presenters about the fixes we were offering for the systemic problems they had listed—over and over, I was told that things “were complicated.” This was a cop-out and it reminded me of Arthur Kleinman writing about numerous failures of the biomedical model and the gloomy future of academic psychiatry. He noted how embarrassing it was to hear psychiatrists hide behind “it’s terribly complicated.”

I spoke with other attending mental health professionals (not psychiatrists) who were similarly perturbed by the fact that no one was addressing deeply and fully what to do and how to help—interventions and treatments. Did we offer treatments that were as systemic as the problems we listed? Could we advocate for better policies and debt relief for farmers? If we can point to rabid capitalism and social alienation as possible causes of student burnout and suicide, then do we have treatments to address these causes? The answer I received was “we can’t do everything,” “this is a wide-ranging question,” “it’s a complex issue.” As if the problems we had been discussing were ever simple!

Behind progressive sounding buzz-words such as “community,” “structural,” and “accessibility” were empty promises and hollow reformations. There was also a real chance of harm! Mental health interventions cost resources. Is it fair to take away financial and medical aid in already resource-poor countries, and reroute it towards interventions that don’t fit the causes—interventions such as psychopharmaceuticals that are under fire for both inefficacy and adverse effects, and are premised upon theories that are now all but discarded? As Dian Million has pointed out, mental health interventions, even when they appear progressive with their purported trauma-informed practices, can still be used to undercut people’s actual needs. For example, native people’s demands for land and water rights in Canada were met with responses that the wronged must receive trauma counseling instead.

Others write that community mental health care workers in rural India have essentially become medication enforcers, regularly dismissing complaints from patients and families about inefficacy and side effects. Is this how the global mental health movement is filling the treatment gap—having non-expert workers cajole or threaten poor rural people into taking medication when many of them haven’t seen a real psychiatrist in two years? Administering dangerous drugs like clozapine without conducting required regular blood tests? In many parts of the Global South, the side effects of psychotropic drugs are even more devastating than they already are in modern Western societies. Physical strength allows people to herd animals, bring water to their village, and so forth, and the adverse-effects of antipsychotics such as dullness and excessive sleep threaten survival.

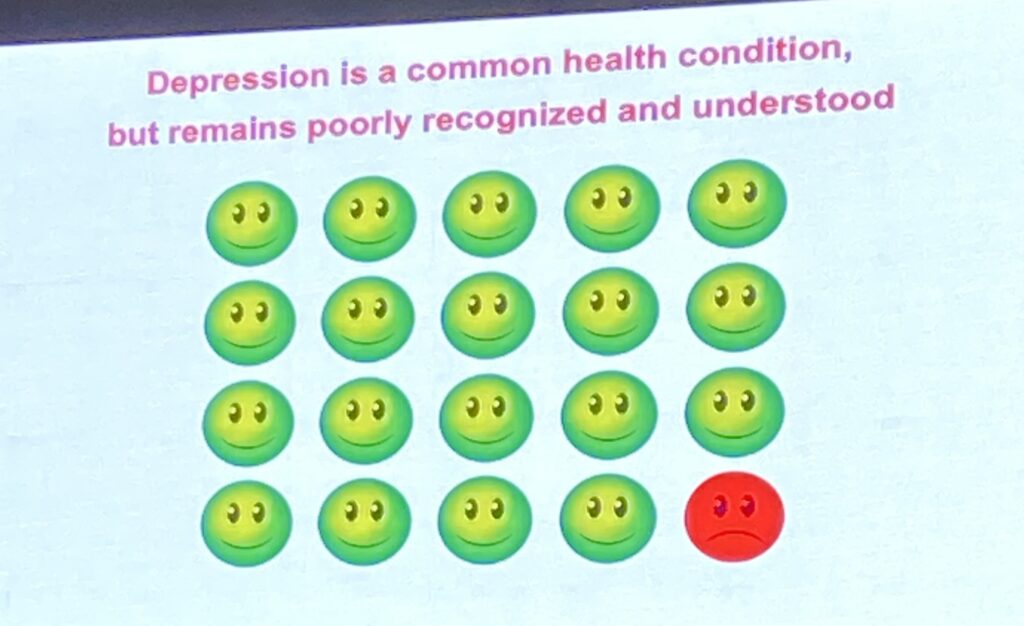

The conference was rife with discussions on stigma of mental illness, which is apparently much worse in the Global South (I sensed a hint of racism here). Nearly everyone mentioned how stigma stops people from seeking help, but no one noted that 1) the help we offer is not terribly safe or effective, 2) mental health stigma campaigns have been spectacular failures, and 3) biomedical psychiatric explanations have been consistently linked to worse stigma. The use of exaggerated statistics, and references to the problematic DALY index and the much-critiqued global burden of disease numbers seemed to point to a global emergency of mental health crisis. This was accompanied by stereotypical pictures of brown and black people, living in poverty, waiting for global saviors. I must mention here that the latter was specifically present in the talks of numerous international presenters (including Indian-origin ones) but thankfully absent from indigenous ones.

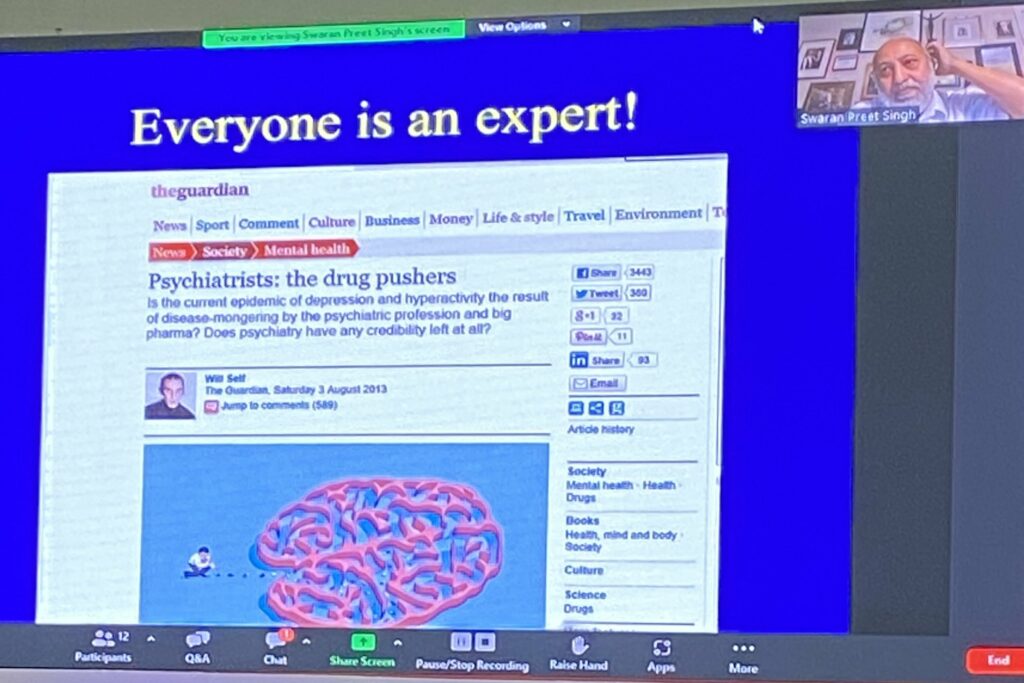

By the end of the third day, my enthusiasm had died and my hope was defeated. It was replaced with resignation, and occasional rage. This peaked with one of the final presentations by Swaran Preet Singh, a psychiatrist from the UK who considered any criticism of psychiatry to be propaganda. He even took issue with journalists writing about kickbacks and industry corruption in psychiatry, saying it was audacious that they thought of themselves as experts (The Guardian received special mention for such reporting).

Reiterating the now laughed-at diabetes metaphor (“mental illness is like diabetes that needs consistent management”), Singh admonished fellow psychiatrists for being internal critics of the discipline, and brought up Joanna Moncrieff and her writings as an example of what a traitor looks like. He clarified that psychiatrists have completely and fully answered all of anti-psychiatry’s questions and yet these critics still keep having issues.

At one point, Singh reiterated Ronald Pies’s disproven claim that no “well-informed” psychiatrist ever believed in the simplistic chemical imbalance theory by saying “I have never met a psychiatrist who said ‘oh, here comes a dysregulated dopamine receptor.’”

When I hear this dismissal from psychiatry, I am reminded of my American undergraduate students. I would ask them if they believed mental health problems were caused by faulty brain chemicals and most said yes. I would inquire who told them about this and most of them cited their primary care doctor or their psychiatrist. Lastly, we would discuss claims by psychiatrists denying that they ever believed in the chemical imbalance theory and I would watch betrayal dawn upon their faces as they realized that they had been lied to, and lied about. After Singh’s talk, there was absolute silence. I was pleased by how flat it fell on the audience.

What gave me hope was that indigenous public sector psychiatrists were deeply critical of the harms and transparent about the limitations of their discipline. They were cognizant of, and sensitive to the realities, of their communities. I am aware that this critical attitude is fast vanishing among the younger generation and private physicians. My colleagues in community healthcare often shared horror stories of meeting patients who had been prescribed 10ish drugs by their provider. This sensitivity was also absent in the international presenters who comfortably fell back into the white savior mode, flanked by pictures of “depressed” brown kids in refugee camps.

As I said at the start of this essay, this experience is not simply about a conference, but is reflective of a wider reflexive and reformative turn that the movement for global mental health says it has taken. In the face of multiple criticisms, the movement decided to incorporate structural determinants, cultural sensitivities, and dialogue with communities into its practices. I believe this is putting lipstick on a pig.

Unless we are open about the grave limitations of our treatments, like some global mental health advocates such as Kleinman have admitted to, we are putting band-aids (toxic band-aids?) on a gaping wound. Unless we decide to find solutions that are as complex and systemic as the problems we discuss, the claims of reformation are nothing more than empty promises. Unless we stop hiding behind phrases such as “it’s complicated,” we will remain an embarrassment. And no amount of forced internal agreement will save us from that.

***

MIA Reports are supported by reader subscriptions and by a grant from Open Excellence. Please subscribe to help fund our original journalism.

What does a scene like this tell me? That the field of so-called “mental health” can no longer hide its utter fecklessness, and, more to the point, its ultimate uselessness, no matter where in the world you find it.

Report comment

….because “depression” is a social condition, not a medical one.

Report comment

“Unless we decide to find solutions that are as complex and systemic as the problems we discuss, the claims of reformation are nothing more than empty promises. Unless we stop hiding behind phrases such as ‘it’s complicated,’ we will remain an embarrassment.”

I agree, the “mental health” industries’ “complex iatrogenesis” is not that “complicated.” The antidepressants and ADHD drugs can create the “bipolar” symptoms. And the “bipolar treatments,” which are largely the same as the “schizophrenia” treatments, can create the positive symptoms of “schizophrenia,” via anticholinergic toxidrome. And they can also create the negative symptoms of “schizophrenia,” via neuroleptic induced deficit disorder.

As one who unwittingly played our current “mental health” industries’ iatrogenic illness creation game, decades ago, so “mental health professionals” could cover up a “bad fix” on a broken bone, and the medical evidence of the sexual abuse of my very young child … at least long enough to prevent me from suing … although I did scare a school into closing forever, once the medical evidence of the child abuse was finally handed over.

I must agree, exporting these systemic “mental health” industries’ / big Pharma’s crimes to the rest of the world, is a really BAD idea.

Good God, they’re embarrassing for me to actually have to discuss.

Report comment

Something funny happened to me when I finally started paying attention to HOW I TRULY FELT taking “anti-depressants” or going to “therapy”:

I realized I DID NOT LIKE and DID NOT NEED to have ANYTHING TO DO with people who believe in “mental illness”.

And guess what? Things in many, many ways HAVE NEVER BEEN BETTER –

Report comment

…and what’s more, I didn’t have to fork over ridiculous amounts of money to talk to some fool or read their damn book, swallow psychiatry’s poison or travel to God knows where TO FEEL AS GOOD AS I DO NOW —

Report comment

“ Elites of the global mental health movement…”

What makes someone an “Elite” in mental health? The number of letters behind their names? The number of papers they have published? Their ability to pontificate endlessly about what is wrong? What exactly makes someone top of their field?

Their professional status is only meaningful to those in the same profession, not to those they purport to “treat”. I would say an “Elite” would be someone credentialed or not who has compassion and understanding that helps someone navigate their distress and despair.

Report comment

What makes someone an “Elite” in mental health?”

The amount of money they make.

P.S. Being “elite” in mental health means you live in an echo chamber.

Report comment

Ayurdhi, thank you for your balanced and important account. I gave a talk about a Far Eastern alternative to Western psychiatry at an international conference in Florence on psychiatry and philosophy. At lunch a young trainee psychiatrist from the UK said ‘Your talk this morning was interesting but it can’t be true.’ ‘Oh, why not?’ I said, ‘Because what you said was so simple and psychiatry is much more complicated than that.’ He had not understood a word.

Report comment

Thank you, Dr Dhar, for an excellent overview of the conference and indeed of contemporary psychiatry. My experience of mainstream psychiatry in the (so-called) ‘developed’ world, is very similar.

Carolyn Quadrio

Report comment

When I envision a world where ALL the money spent on “mental health care” AND “allopathic healthcare for chronic illness” is completely funneled into other areas (Besides the pockets of already rich people of course)

I then see that the need for mental and chronic illness healthcare decreases to practically zero.

But I’m not an “elite” professional.

Professional “elites” take people with insight out of commission by drugging them then telling others that the affects of those drugs mean those people lack insight and to not pay attention to them.

Toto is a very undervalued, under-appreciated, underrated and overlooked character in The Wizard of Oz. The writer made a little dog the one who pulls the curtain to expose fraud for a reason. Modern day version: The author would have Dorothy take him to the vet who puts him on Prozac for that incessant barking!

Report comment

“Professional ‘elites’ take people with insight out of commission by drugging them then telling others that the effects of those drugs mean those people lack insight and to not pay attention to them.”

Thank you for mentioning psychiatry’s standard protocol. It’s exactly how psychiatric residents are trained.

And yes, psychiatric drugs are an easy way to invisibly muzzle people.

Report comment

Another essential article Ayurdhi Dhar, thank you!

As I was reading this article, I wondered how some of the promising attitudes and positions held by various clinicians, were going to be disseminated back into vast communities? Unfortunately I’d been completely disabused of this concern by the time I finished the “it’s complicated” portion of the essay. Suffice to say, institutional mental health isn’t in the business of treating mental health, it’s in the “business” of applying silver bullets to the symptoms of mental health; which is to say invested in their own professional self interest at the expense of the welfare of their respective charge.

Report comment

I failed to mention that, even before institutional mental health begins treating the symptoms of mental and emotional suffering, it must, above all else, first control the narrative of what the mental/psyche, emotional problem/issue is: name it, define it, and control both through whatever means necessary. Hence the word “Disorder”, a word that, when deconstructed, and historically and socially recontextualized from its (political) myriad of decontextualized origins, is a weaponized word that subverts critical consciousness and substantive psychic and emotional progress.

Report comment

Oh, my goodness, if ONLY we could have had such utterly splendid reportage from Ayurdhi Dhar from the First Council of Nicaea, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_Council_of_Nicaea , faithfully recording for us how the Emperor Constantine did or did not ?foist ( https://www.etymonline.com/word/foist ) his doctrine of

homoousios, https://www.britannica.com/topic/homoousios , onto it, we might have such a VERY different world now.

Ditto of India had much of India managed to stay closer to the Emperor Ashoka, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ashoka – or had Ayurdhi managed to explain his thinking worldwide.

Perhaps Ayurdhi missed an opening welcome speech, perhaps like one to be given at the next such conference, wherein someone quoted from the Upanishads, before going on to rejoice that Eckhart Tolle –

“You do not become good by trying to be good, but by finding the goodness that is already within you, and allowing that goodness to emerge. But it can only emerge if something fundamental changes in your state of consciousness…” –

among others, has now taken us beyond even some of the Upanishads and explained with piercing clarity that, thus far, that we are indeed all equal, after all, even if those Founding Fathers did not and could not explain how, but still rather ?foisted the notion forward,

“The human condition: lost in thought…”

and that the psyche is not merely the mind, our thoughts and emotions,

but that, however infinitely significant it may be, the mind an infinitesimally tiny portion or aspect of the individual and collective awareness which can observe and learn to direct the individual and collective mind

(and that physical pain is not created or generated or sensed or perceived by certain nerve endings, but by the mind, whenever fear is activated

https://mail.google.com/mail/u/0/#search/schubiner+/KtbxLvhVdtvnKqhrWKRXJhdzPxPpFmPXpL?projector=1

and that the notions of “pain-receptors,” of “nociceptors” and of “nociceptive pathways” are erroneous, though still pervasive).

“As a caterpillar, having come to the end of one blade of grass, draws itself together and reaches out for the next, so the Self, having come to the end of one life and dispelled all ignorance, gathers in his facilities and reaches out from the old body to a new.

As a goldsmith fashions an old ornament into a new and more beautiful one, so the Self, having reached the end of the last life and dispelled all ignorance, makes for himself a new, more beautiful shape, like that of the devas or other celestial beings.

The Self is indeed Brahman, but through ignorance people identify with intellect, mind, senses, passions and the elements of earth, water, air, space, and fire. That is why the Self appears to be this and that, and appears to be everything.

As a person acts, so he becomes in life. those who do good become good; those who do harm become bad. Good deeds make one pure; bad deeds make one impure. You are what your deep, driving desire is. As your desire is, so is your will. As your will is, so is your deed. as your deed is, so is your destiny.”

“Not that which the eye can see, but that whereby the eye can see: know that to be Brahman the eternal, and not what people here adore;

Not that which the ear can hear, but that whereby the ear can hear: know that to be Brahman the eternal, and not what people here adore;

Not that which speech can illuminate, but that by which speech can be illuminated: know that to be Brahman the eternal, and not what people here adore;

Not that which the mind can think, but that whereby the mind can think: know that to be Brahman the eternal, and not what people here adore.”

Thank you, thank you, thank you, Ayurdhi Dhar and MIA for still more absolutely superb reporting.

Happy Independence Day, one and all – equally!

Tom.

Report comment

There is no good, bad or complicated: there is just the false, the untrue, the technocratic method used by society to manage problems of a profundity and complexity that goes far beyond their understanding, and I am talking of psychiatry. They live in a conceptual reality composed of nothing but words, but you do to, which is why your eyes don’t strip psychiatry and society naked and show their meat and bone machines inside. Otherwise, when you looked in the mirror they would do the same to you, and you would realize that you are society and psychiatry dominating a meat and bone machine inside. I’m afraid that I don’t exaggerate. It’s social and historical invention, proliferation, social ossification, neurological entrenchment, shaping the expression of all your thinking and life activity which recreates and maintains this society by turning you into an unhappy, striving egoist, a production line human being. If you were happy you wouldn’t strive. If you were happy you would be free, creative, not a production line human being, and therefore an impossible threat to society.

Because if your brain becomes whole, it has an intelligence vastly superior to society. What kind of intelligence can a divided and fragmented society and knowledge have compared to that which synthasises and mobilizes not just knowledge, but all perceptions and understandings that go beyond words? But if your brain was whole, it would be a threat to society. It would destroy the society in black flames. It would liberate or destroy each and every single one of us for eternity. The liberation or destruction is according to the judgement which you invented, or which were produced by social history which conditioned you to possess them, apply them.

I saw two presidents of the USA and I couldn’t tell what was soma and what was tumour. People like that belong in morgues or cemeteries. And if that is the flowering of 250 years of American empire, or more accurately, 900 years of British history, then it is proof that Britain and America are a disease that flowered into the civilization that’s destroyed the Earth today. And now it conditions your children to do exactly the same. You call this system democracy. Only when there is no love or freedom is there a need for a democracy and a rule of law. These are symptoms of disease and you hold them up as your highest values. And then you scatter into your many mouseholes.

Report comment

“But if your brain was whole, it would be a threat to society.”

Intelligent people often frighten the stupid.

Report comment

CORRECTION: Healthy people often frighten those who are not.

Report comment

People who have awakened often frighten those who have not, (imho).

Report comment

… and feelings of sorrow and worry can be signs of emotional health, (imho).

Report comment

Hi, Birdsong.

I balk at the terms “mental health,” “mental well being,” “mental illness,” mental disorder,” and “personality disorder.”

Can you define your term, “emotional health,” for us, please?

And, if it exists, does that mean that emotional ill-health, illness or disorders do, too?

Best wishes.l always!

Tom.

Report comment

Hi Tom,

That’s good question that I’m not quite sure how to answer. So, how does emotional equilibrium sound to you?

The term ’emotional health’ is one I try to stay away from because it implies that there’s an opposite, that being ’emotional illness’, a concept I don’t agree with. I must have been in a rush…

Report comment

What people need to understand about you Birdsong is that in every word you say, you are always BANG ON, which means you see and understand your reality. To the extent people don’t understand you, that’s there problem! 😀

Report comment

Why thank you, No-one. I think your answers are BANG ON, too! 🙂

Report comment

No-one, I tend to think a lot of people who don’t understand me actually do, but this becomes a problem for them when they can’t admit that they actually do. In other words, I tend to think there’s a lot of denial at play, which usually happens whenever you make someone question their world view and their place in it.

Report comment

“Only when there is no love or freedom is there a need for a democracy and a rule of law. These are symptoms of disease and you hold them up as your highest values. And then you scatter into your many mouseholes.”

Values and ideals are wonderful things. It’s what sets humans apart from the rest of the animal kingdom.

But humans are human, they are not gods, which means that things like selfishness and aggression (human nature) will always be present.

P.S. And there’s nothing wrong with mouseholes. We need them to survive.

Report comment

“The hearts of men are easily corrupted.” – J.R.R. Tolkien

“To Be hopeful in bad times is not just foolishly romantic. It is based on the fact that human history is not only a history of cruelty, but also of compassion, sacrifice, courage and kindness… The future is an infinite succession of presents, and to live now as we think that human beings should live—in defiance of all that is bad around us—is itself a marvelous victory.” – Howard Zinn

“What Is The Nature Of Human Nature”, in Values of the Wise

Report comment

Birdsong, in reply to your other comment (as I seem unable to reply directly above: sorry!),

“So, how does emotional equilibrium sound to you?”,

I would say “VERY interesting, indeed, thank you!”

Hasty or not, your comment on “emotional health” set me thinking anew these past two days, and to my immense reward, thank YOU, Birdsong!

I finally began to understand, I think, that perhaps no emotional high is ever experienced without some payback.

For all I know, a neuroscientist MIGHT suggest that the very metabolizing and excreting of the biochemicals involved in any emotional high tend to leave a toxic, hangover-like effect.

However Nature achieves it, we seem unable to have highs without lows.

So maybe those Founding Fathers condemned us to endlessly pursue happiness in roller-coaster rides when, had they only known it themselves, they might have advised or even taught us to find peace, and with it joy and beauty and creativity and inspiration…withIN?

However you did it, Birdsong – and I do fully acknowledge that your entire M.O. here seems to be to do all you can to help alleviate human suffering and persecution and to do ll you can to write to bring comfort and peace and joy and enlightenment – whether in haste or no, you CERTAINLY brought me abruptly to a most stunning and most immensely reassuring realization, the realization that I really can now quit seeking ANY emotional highs, and, instead, to rest content with growing peace and joy and acceptance of whatEVER Life throws me, instead!

Not so much the pearl-of-great-price, but the pearl-beyond-any-price, I reckon.

So thank YOU – very, VERY much, indeed, Birdsong!

And thank you for your haste!

Tom.

To err is divine; to forgive, human.

PS: Rather than dwell on human weakness and corruption, one of my favorite passages from “The Lord of the Rings” trilogy movie, and which you may tell me does not appear in the book, has to be a speech seeking to rally humans against our common enemy, Fear:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QdtmlfLFgWg

…and the other deals with what I see here daily in these very pages, the kindling of Human Hope, the lighting of great beacons for all humanity to see:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fyIjoXv6Y-0

Report comment

Tom, thank you for saying such kind things.

P.S. I wouldn’t knock happiness if I were you because imo it sure beats the alternative. Just make sure you don’t get carried away with it. That goes for the lows, too, btw.

Report comment

Spot on, No-one. Bleak and depressing but refreshingly true as well. Thank you. What you just said needs to be said, loudly, again and again, by more and more people. Maybe then, at least, humans won’t be put down so easily…

Report comment

Thank you so much, Ayurdhi, for this excellent report. I read it very sympathetically from day one where hope and gladness were there to day three where it had become rage and disappointment. I was reminded a lot of my own experiences with groups of people who are working within psychiatry to reform psychiatry on the one hand and the psychiatrists and doctors who work in more conservative tracks on the other – who both failed me terribly when I was seeking help.

Some of your detailed obsevations are very important for me because I share your perspectives even on the parts of psychiatry where people think their work is more helpful than the old routines and for example foster “trauma-informed” care. When actually they are depolitizising and psychiatrizing the experiences of people who have experienced violence and injustice.

What is surprising and not surprising for me at the same time: How it is described that the people trained in the clinical psy-disciplines at that conference actually do not know how they could be of real help and assistance to people who go through challenges of their mental health or whose struggles have become chronic.

Because my experience was just that. That they have nothing what works.

I was lucky that I had the chance to try medication and talk therapy for my chronic episodic depression and debilitating social anxiety. From doing that I found out soon and from my own experience that compared with an hour of yoga a day, a depression self-help group and a self-led anxiety desensitivization training with the advice for the Tibetan woman warrior they were fairly useless or worse, harmful.

That said, I think it is sad that the psy-experts of India know so little of the psychological theories and practices to foster balance and peace within the mind and bring about an inner liberation from suffering that were brought forward by the ascetics and sages of their own country.

I am currently reading “Living This Life Fully. Stories and teachings of Munindra (Barua)” authored by Mirka Knaster about one of the most important vipassana (insight meditation) teachers of the 20th century who mainly tought in Bodh Gaia. He was very important for the global vipassana movement because he was a key teacher for making the meditation practices and the Buddhist teachings from the Southern schools available again or accessible to people from India and Bangladesh, and North and South America, Europe and East Asia.

I am studying and practicing with some teachers who were his students or a generation younger. I can recommend it very much. As long as psychiatry can’t offer us a fix I think everyone should at least give yoga and other “spiritual” practices like prayer and meditation a shot.

I put “spiritual” in quotation marks because I think we should rather call them housekeeping for the heart and mind. These practices are actually really down to earth and unfold a healing effect already after the first lesson.

Report comment

“I put “spiritual” in quotation marks because I think we should rather call them housekeeping for the heart and mind.” – love it! If so called ‘spiritual’ people understood this point they wouldn’t be the over-excited absurdities in cloud cuckoo land that they generally have become today. I’m not criticising – I’m in cloud cuckoo land too, but knowing as much means I’m not also in lala land at the very same time. Anyway, I’ll send you a postcard Lina to your nice little American abode in Sane City. I know only you and Birdsong live there, so do send Birdsong my regards.

Report comment

At any Earthly world ophthalmology conference, one might expect to learn about and even to witness demonstrations of the latest techniques to preserve or restore vision, preferably 20:20 vision.

At any Earthly world conferences on orthopedics, oncology etc., one might expect to learn about new approaches to old problems, and for helping restore full, painfree locomotion, function…

At any Earthly world psychiatric conference, some foolish – some other-worldly-unwise but otherwise intelligent – alien being might be expected to expect to learn what a fully functioning, “normal-standard” humanoid might be expected to resemble – at least from the point of view of Planet Earth’s psychiatrists.

That alien might fully expect to see a Ramana Maharshi, Jiddhu Krishnmurti, Mohandas Gandhi, Dolly Parton, Judy Tenuta, Desmond Tutu, Taylor Swift, Teresa of Avila, “Julian” of Norwich, Viktor Frankl (even if he was a psychiatrist), Paramahansa Yogananda, Jesus of Nazareth, Joan of Arc, John Steinbeck or some such, or the chair of some DSM committee wheeled on as a model form of what supposedly full function looks like.

That alien might be mightily disappointed and reasonably ask “What gives, guys?” or “So, what passes for ‘100% normal’ here, please?”

At our old vet college in Dublin Ireland, dear old (professor of large animal surgery) John Patrick O’Connor endlessly pleaded with students never to get too proud:

“You’ll be treating animals for antibiotic-deficiency for the rest of your lives,”

(had he been lecturing medics, I guess he might have spoken of “‘antidepressant’-deficiencies”)

“Please, please, please, ladies and gentlemen,endlessly take every possible opportunity to try and familiarize yourselves with the NORMAL!,”

“God gave horses pairs of legs so that veterinary surgeons could compare one with the other,”

and he reminded us that

“THE worst animal diseases of all, ladies and gentlemen, is…the veterinary disease!” – meaning any injury inflicted on an animal by a vet, or any iatrogenic disease, such as a barbiturate-induced jugular slough.

Had John been lecturing medics, I guess he might have spoken of “psychiatric diseases.”

But even the great professor himself failed to ask Brian Brennan to lecture and to demonstrate what may one day become a normal behavior for vets, at least.

In fairness, Prof. O’Connor, perhaps he never heard about what had happened when Brian had walked into that horse box, the one in which stood the colt so crazed with fear that no one, but NO one, not even the most experienced “yardman” on the staff, had been able to approach him. It was said that anyone daring to enter that stable immediately found her/himself being maneuvered towards a corner wherein the flying hind hooves threatened to pulverize the trespasser.

But our classmate, Brian, was a horse whisperer. And Brian, it was told in disbelief, had calmly entered the stall, simply walked up to that horse’s head, and petted him.

“Why,” I asked another erstwhile classmate today, did no member of staff ask Brian to explain, demonstrate or teach this magic to all the College?”

And then it was, decades later, that it occurred to me:

“Why didn’t YOU, who shared an apartment with Brian, ask him, Tom Kelly?!”

Thanks, again, for such a tremendous report.

Tom.

“If the blind shall lead the blind, then both shall fall in the pit!”

Report comment