Portrayals of “mental illness” in media are a long-standing controversial topic. How to avoid romanticizing, how to avoid stigmatizing, how to avoid triggering audience members who may share similar experiences—these are all valid concerns. But perhaps more importantly—and at the center of them all—who’s holding the narrative? And whose narrative does it align with?

Recently, I finished reading a memoir that encompassed subject matter including emotional abuse and eating disorders (EDs), both of which I have personal experience with. Initially, I was concerned about how the material might trigger me, so I was sure to continually check in with myself as I was reading. But despite graphic detail about self-induced vomiting, caloric restriction, extreme overexercising, and memories of abuse alarmingly similar to my own, I ended up being surprised: These were not the parts that I found triggering. The parts that I did find triggering were about the author’s recovery from their ED.

Why was this? Well, I am a psychiatric survivor with trauma from ED treatment and sanism. That could explain why the treatment-related parts bothered me, but not why the ED and abuse-related parts didn’t; those traumas didn’t cause my other traumas to disappear. I’ve read book reviews stating that this memoir was triggering for those with EDs. I realized that it would’ve been for me a few years ago, too, though I can’t say the difference is simply because I’m recovering now. There must be something deeper.

The Narrative

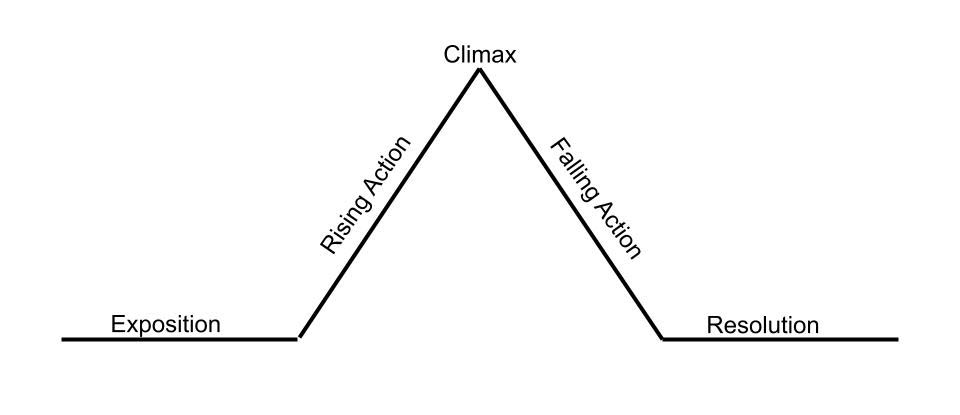

We talk about “the mainstream narrative of mental illness” all the time here in the critical psychiatry realm, yet we hardly ever bother to define it. So…what is it? Well, any narrative must have a proper narrative arc, of course. It goes something like this:

Exposition: Establish protagonist (main character), the afflicted.

Rising Action: Establish conflict: Symptom onset. Illness develops.

Climax: Protagonist confronts their obstacle, seeking professional help and receiving a clinical diagnosis.

Falling Action: Protagonist diligently attends therapy and/or takes medication, and starts to get better.

Resolution: Full recovery! Victory!

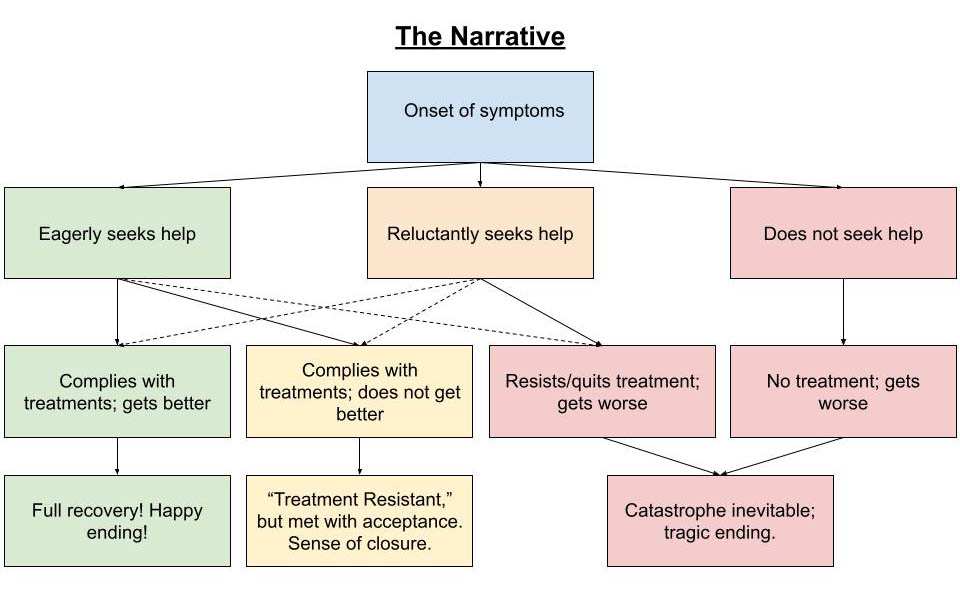

Evidently, this narrative does not leave very much wiggle room. There is good reason why the “Success Story” is the most dominant narrative endorsed by the Mental Health Industrial Complex (MHIC), society in general, and “mental health awareness” advocates: It encourages people to seek professional services with the underlying message that a desirable outcome from mental health treatment is guaranteed. Because it is such effective marketing, the Success Story is the compelling story arc that most of us psychiatric survivors initially thought we were signing up for.

However, since its treatments are only “effective” part of the time, the MHIC must find a way to account for any alternate routes that a patient’s journey may take. Rather than simply ignoring these alternate possibilities altogether, it is crucial for the MHIC to maintain control of these narratives as well. They generally take on one of three forms—the “Treatment Resistant,” the “Non-Compliant,” and the “Cautionary Tale.”

The Exposition, Rising Action, and Climax of the Treatment Resistant arc are identical to the Success Story. It differs after the Climax, something like this:

Falling Action: Protagonist is diligently attending therapy and/or taking medication. They may improve somewhat at first, but symptoms always seem to reappear. They try different combinations of different treatments. Still no luck.

Resolution: Protagonist is informed that their mental illness is treatment resistant. Though they will need to depend on treatments for the rest of their life to manage their symptoms, they may never make a full recovery. With this knowledge, they come to a point of acceptance about their condition.

The Treatment Resistant narrative is less widely known than the Success Story, and is typically thought of as a rare exception, only introduced to patients after they have already been seeking treatment for some time without improvement. Although the ending is not as satisfying as the Success Story’s, we still get a sense of closure. The protagonist is still regarded as a “Good Patient.” They did everything they were supposed to do: seeking help, trying hard to find the right treatment, and accepting everything their doctor told them. Even though mental health treatments failed them, it was conveniently reframed as a failure of the patient instead—not of their character, but of their biology—and they did not question or challenge this notion.

But what about when things still don’t go according to plan? What about when a patient does question or challenge the MHIC instead of accepting everything they’re told? How does the MHIC not only encourage people to use services, but also discourage people from not using services? Well, this is where the “Bad Patient” tales come into play: the Non-Compliant and the Cautionary Tale. In the Non-Compliant story arc, the protagonist is presented as not willing to face their problems. Though they may be reluctant to seek help, they eventually do, whether by choice or by force. However, their unwillingness persists throughout treatment, and they may eventually quit their medications or therapy suddenly. Their rash choices result in their own demise, causing disastrous consequences: potentially even violence, homicide, or suicide. The Cautionary Tale, on the other hand, ends similarly, though the primary difference is that the Non-Compliant refuses services that are offered, whereas the Cautionary Tale never obtains services in the first place. This framing presents the Cautionary Tale as a literal “cautionary tale” of “untreated mental illness.”

Both of these Bad Patient narratives, alongside the Good Patient narratives, serve an important purpose for the MHIC. There may be some variation on these prototypes (for example, one could start out reluctant to seek help but become compliant later on), but for the most part, they all weave together seamlessly into “The Narrative.” Although these are the prevailing narratives in which the patient takes center stage as the protagonist, in other versions of the story, the patient may play a side character—or even villain—in someone else’s story; usually a family member, romantic partner, or even a mental health professional. Their feelings, perceptions, and judgments about the patient are centered above the patient’s own. In any case, none of these narratives can leave room for a positive outcome from denying diagnosis and refusing treatment, or never seeking treatment in the first place, nor a negative outcome from accepting a diagnosis and complying with treatment. Any dissenting voices must be either consumed or silenced altogether.

Narrative and Power

It is often said that life imitates art. The media we consume plays a crucial role in shaping our cultural and personal narratives. The mental health narratives above are often what we see represented in movies, books, TV shows, and other media portrayals of those deemed “mentally ill.” In fact, many pro-mental health advocates might see those narratives as responsible portrayals of “mental illness.” Getting help equals recovery. Resisting, refusing, or failing to access help equals imminent destruction. After all, we wouldn’t want to romanticize mental illness, or stigmatize getting help, or trigger someone into a relapse, would we? But what exactly makes a piece of media triggering? And how could this explain why I unexpectedly found some parts of the aforementioned memoir triggering and not others? To answer these questions, we must first define “trigger.”

A trigger is typically defined as a stimulus that worsens mental health symptoms. A graphic depiction of violence may be considered triggering to someone diagnosed with PTSD. A graphic depiction of substance use may be considered triggering to someone who struggles with substance use. A graphic depiction of ED behaviors may be considered triggering to someone with a history of disordered eating. Or that’s how it’s typically thought of, at least.

But I would like to take this definition one step further. If we recognize that most “mental illnesses” are really symptoms of trauma (or coping behaviors to deal with trauma), then any “mental illness trigger” is really a trauma trigger. So we can reframe our definition from “a stimulus that worsens mental health symptoms” to “a stimulus that worsens symptoms of trauma.” Well then… how do we define trauma?

“Trauma” is another word that we hear quite often in both the mental health realm and the critical psychiatry realm alike, while rarely ever getting a proper definition. Most may think of trauma as “a really bad event in a person’s life” or “something that leaves psychological scars.” Both of these are fine definitions. After all, trauma means different things to different people. Perhaps it is best, in some ways, not to have a one-size-fits-all universal definition. But… why does trauma mean different things to different people? And why do certain triggers bother some people and not others?

Despite the lack of universality of trauma, I shall attempt a universal definition in a way that accounts for the lack of universality itself: Trauma is, at its core, a profoundly disempowering experience. It strips an individual of their autonomy, agency, and/or voice, rendering them functionally powerless. Trauma forces one to become the victim of a story that they did not write, choose, or consent to. One could say that trauma robs its victim of their narrative. Sure, trauma could also be a lot of other things; it isn’t only about disempowerment. Trauma can be about betrayal. Trauma can be about a lack of safety. Trauma can be about grief. But while not all forms of trauma may be about betrayal or safety or grief, I would argue that what all forms of trauma do have in common is disempowerment. Since everyone’s personal narrative is different, and therefore the narratives they encounter will impact them in different ways, this may explain why there is no universal definition, and different people experience trauma as different things. Not every clashing of narratives indicates trauma, however – multiple narratives can coexist – but trauma occurs specifically when one narrative is imposed upon another person at the cost of their own, accompanied by power imbalance and nonconsent.

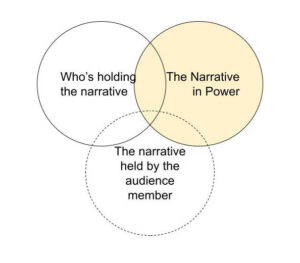

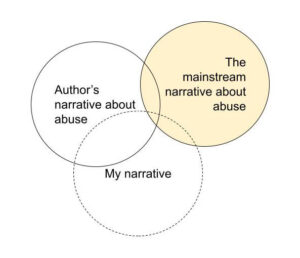

So if a “trigger” is defined as “a stimulus that worsens mental health symptoms,” and “mental health symptoms” can be understood as “trauma symptoms,” and “trauma” can be understood as “disempowerment” or “a robbing of one’s narrative,” then it would logically follow that a “trigger” can come to be understood as “a reinforcement or reenactment of a narrative that disempowers.” In other words, whether or not something will trigger someone depends less on what’s being portrayed, and more on how it’s being portrayed, namely 1) who’s holding the narrative, 2) the narrative in power, and 3) the narrative held by the audience member themselves. How these three narratives align or misalign will largely inform whether or not something will be experienced as disempowering – and therefore triggering – by a given audience member.

Example: The Memoir

In addition to the general “mental illness” narrative, the widely held narrative on EDs includes the idea that EDs are inherently competitive. This is the default justification for why detailed descriptions of ED symptoms or behaviors may be “triggering” to those with EDs. If an ED sufferer feels that their symptoms are not as bad as the symptoms being described (e.g. their weight or caloric intake is not as low), they may feel as though they are “not sick enough” by comparison, thus motivating them to engage in the described behaviors in order to feel valid.

Although I bought into this narrative myself for many years, I now believe it takes too many shortcuts, obscuring the real reason for this apparent “competitiveness”: the diagnostic criteria and setup of the MHIC itself. As I wrote in The “Sick Enough” Paradox in Eating Disorder Treatment, the arbitrary DSM criteria that determine whether or not someone may qualify for a diagnosis and/or ED-related healthcare necessitates that patients “prove” they are “sick enough” in order to obtain resources. Gatekeeping of resources brought on by a capitalist healthcare-as-business framework induces manufactured scarcity and subliminally encourages sufferers to “compete” with one another for access. If, for example, an individual is engaging in restrictive eating and experiencing mental and physical distress, yet they are not “clinically underweight” according to BMI, and when they seek help they are told they “don’t really have a problem”—and are perhaps even praised for their weight loss and “disciplined” eating and exercising regimen – what kind of response is that likely to elicit? Could that perhaps encourage someone to believe they need to lose more weight and engage in more behaviors in order to be taken seriously and get their needs met? Beyond the practical implications alone, there is the human desire for one’s pain to be seen and validated by others; the experience of being told it’s “not bad enough” can feel invisibilizing. However, like most issues within the MHIC—such as “treatment resistance” and “non-compliance”—this phenomenon is conveniently reframed as the fault of the patient or the nature of the illness itself.

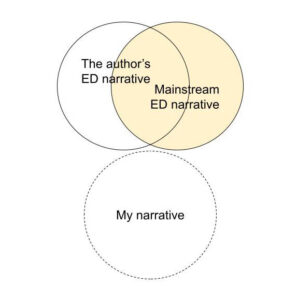

This is why, a few years ago, reading this memoir could’ve easily triggered me. Because my narrative was ruled by the mainstream narrative of EDs, and my ability to access care or even compassion was contingent upon how well I conformed to this narrative in the eyes of others, I was constantly plagued by this “not sick enough” imposter syndrome. Any narrative that reflected and conformed to the mainstream narrative “better” than I did—according to behaviors, symptoms, physical appearance, etc.—felt like competition. I would’ve even read stories like this as “motivation” to “help” me lose weight. Though I realized I was doing this, I would not have been able to articulate an explanation at the time, except by falling back on that which had conveniently been provided to me: It’s just my sick brain. Yet another narrative imposed upon me by the MHIC.

At the root of my psychiatric trauma was the disempowerment I experienced from the MHIC. This was reflected in the author’s descriptions of therapy, and even how others treated them regarding their ED. They described their partner threatening to break up with them if they did not seek professional help, their friends quietly surveilling them at meals, and their therapist forcing things that made them uncomfortable. However, none of this was portrayed as problematic. Their partner, friends, and therapist were all cast in a flattering light of simply being concerned. They were “good” and “right.” The ED was “bad” and “wrong.” Although these paternalizing, pathologizing, power-stripping dynamics sounded familiar to me, the author’s narrative of them very much did not align with my own. Instead, they aligned with the mainstream narrative. This misalignment catalyzed a mental reenactment of the initial disempowerment I felt from the MHIC, ED treatment, and sanism, reinforcing a dominant narrative that had eclipsed my own. In one word, I felt “triggered.”

The reason why these segments bothered me far more than the parts detailing emotional abuse is because the author clearly recognized the emotional abuse as being “bad,” and the person(s) enacting the abuse as “wrong.” Rather than triggering, this actually felt validating to my experience. Our narratives aligned. Although the mainstream narrative on abuse is generally condemnatory of it, emotional abuse in particular is often underrecognized. I’ve seen other portrayals of emotional abuse in media that do feel triggering, and this is typically because the behavior being portrayed is not even recognized as abusive or “wrong,” and may even be romanticized. Thus, seeing my own narrative represented in the author’s felt empowering.

Trigger Warnings vs Censorship

Nearly any media portrayal or discussion of “mental illness” or trauma is likely to be deemed “sensitive content,” oftentimes with a “trigger warning” applied accordingly. This awareness and sensitivity towards “mental health issues” may be considered progress on some fronts. However, since triggers can be so variable even amongst people with similar traumas or mental health labels, and they depend more on individual, authorial, and cultural narrative alignment than the actual subject matter itself, it calls into question the usefulness of such “trigger warnings” to those that they are, in theory, meant to protect.

Perhaps trigger warnings can sometimes be helpful to survivors in making informed decisions about the kind of content they consume during their recovery. However, “Trigger Warning: ED” or “TW: abuse” tells me very little about if and how much something will trigger me. Furthermore, as a survivor, I sometimes actively want to consume media about EDs, emotional abuse, psychiatric trauma, etc.—not as an act of self-sabotage, but as a recovery tool. Finding relatable art and stories—by survivors, for survivors—not only helps me feel less alone; it also helps heal the wounds of disempowerment by making me feel seen and heard while challenging the dominant narratives that invisibilized and silenced mine.

However, when these stories are sanitized for fear of bringing harm, they no longer hold the same power. Trigger warnings can be not only unhelpful, but even damaging to those they claim to protect, increasing stigma and reinforcing taboos. People forget that survivors can be more than passive audiences to these stories; we are often the storytellers ourselves. By putting trigger warnings on the content we consume, it implies that we must, in turn, place trigger warnings on what we share. This sends a subliminal message: that our stories are triggering, our bodies are triggering, our voices are triggering, our very existence is inherently triggering to others. So we fall back into invisibility and silence. We learn to self-censor for fear of causing harm, without consideration for the harm it is causing us, and the potential good that our unsuppressed truth could do for ourselves and others. This forces us to relive the dynamics of disempowerment and narrative-robbing that created our trauma in the first place. In short, trigger warnings are not always meant to protect the vulnerable: They are meant to protect the status quo.

“Romanticizing” vs “Stigmatizing”

“Romanticizing mental illness” or, on the other hand, “stigmatizing mental illness,” are also common talking points in the media portrayal debate. Any representation of “mental illness” outside of the dominant narrative seems to fall prey to these accusations. Like trigger warnings, however, these concerns masquerade as protecting the “mentally ill,” while in practice being weaponized against those most vulnerable. When we, survivors, share our experiences of madness in a positive way—especially more stigmatized experiences/behaviors, like voice hearing, self-harm, and suicidality—we are accused of “romanticizing” it. On the other hand, the “sane” are able to get away with glamorizing and commodifying our struggles all they want. When we share any negative experiences—especially of mental health treatment—we may be accused of perpetuating “stigma.” Meanwhile, the “sane” portray us as villains of horror movies and scapegoats for gun violence without criticism. There is a clear double standard here: Stories are far more scrutinized when the Mad tell them. But the thing is, when you romanticize or stigmatize what’s yours, that’s not “romanticization”/ “stigmatization,” that’s narrative reclamation. When you romanticize or stigmatize what isn’t yours to begin with, that’s narrative robbing. It matters who is holding these narratives: survivors or “experts,” patients or doctors, Mad or “sane,” those who’ve lived it or those who’ve studied it.

Closing Thoughts

Narratives hold power. The portrayals of “mental illness” we consume through media can be dangerous to those most vulnerable. But the solution isn’t censorship, nor is it simply more representation. To quote trans activist Alok Vaid-Menon: “I actually think we’re overrepresented in media by their projections, and we’re underrepresented in media by our realities. And the crisis of trans [or Mad] America is that we prioritize cis [or sane] people’s anxieties and insecurities about us over our actual lives.” Although this quote was originally said in regards to trans media representation, the same could be said of Mad media representation. “Sane” understandings of Mad experiences take precedence over Mad ones. “Sane” discomfort is prioritized over Mad suffering. Only the Mad who conform to sanist ideas of madness and recovery are allowed to participate in this monopoly of narrative. This is not to say that they do not have a right to share their stories. But they surely do not represent all of us. And sometimes, proximity to saneness and power can motivate some Mad people to silence the dissenting voices of other, less conforming, Mad people. Any alternative narratives may feel like a threat to their own, and therefore to the fragile stability afforded them by conditional sane acceptance. However, allowing space for narratives that fall outside these norms does not take away from theirs, but adds to it.

As Mad people and trauma survivors, sharing our stories (when safe to do so) can be a profoundly empowering experience. If the opposite of trauma is healing, then the opposite of narrative theft is narrative reclamation. We deserve and need to create our own representation through stories and art—for ourselves and each other—even if they don’t make it mainstream. Our voices matter. Narratives have the power to lock us up—sometimes literally. But they also have the power to set us free.

How has it come to pass that real, actual, exquisitely intelligent and complex things called human beings ever become so degraded that they have to be subject to this thing you call media portrayals of mental health? Now that’s insanity. It’s because the majority of people, including all heavily conditioned professions like media, psychiatry, business, law, policing and government, have had their brains utterly destroyed by ideologies, prejudices, social and ‘professional’ conditioning, conspiracy theories and every kind of propaganda. We talk of changing minds, as if this could be a solution, but ones whole brains, actions and lives become conditioned by these ideological lies and conspiracy theories. You can’t just fix it all with a magic wand. The 7 billion socially conditioned greed machines, the 7 billion self-fattening pigs that destroyed the Earth, will have to go, otherwise it is the whole of Mother Earth who goes, and every life system that lives on her. So how to preach sanity to a brain destroyed? See this truth and thereby destroy your own insanity.

Report comment

A Poem

A Way to Meet the Sky

A Way to See the Future

The phenomenon is just a wonderful in the All-Look’s gaze.

Wonderful we see that,

and wonderful we see each other,

and a panda is to us the moon

and a dog the starry sky.

Can you get there?

All life has eyes,

and oh the splash of healing there,

phenomenal.

You’re scaring us.

Mom, dad, and I are worried about you.

You’re not gonna abduct us, are you?

Who made the volcano?

Let’s start over.

How many notions can you make shake,

eight billion?

Each one of them should die

because they’re from outer space,

crapped on Mother Earth?

They did not come from her?

Where are you goin’?

They’re all stupid and you are too?

The lion is stupid

and the crocodile.

The elephant doesn’t see it either:

Mother Nature has eyes;

she’s an organism.

She’s put on her thinking top.

She’s a thinking organism.

Man does that,

has reached that height of thought

she can see herself.

Conspiracy this, will yah?

Never mind it’s dumb thinking.

There’s a plan here,

an actual plan:

let it all hang out.

Shoot people and murder

and destroy the planet,

I could list a lot of dumb things.

I mean a buffalo would do it too

if they were in charge,

the apex species.

You think they’d just eat tall grass?

Wow, what’s goin’ on here?

Well the buffalo isn’t that smart

I’ll grant you that.

We are cavemen.

It’s all a big charade

we got technology;

we’re as dumb as they come

where we find notions for each other

and the Earth.

So we destroy,

or get so paranoid we do,

using excuses we’ve gathered in soups,

an internet cafe for example.

My, my, there are so many of us,

fattening pigs.

Is that the notion you wear?

They should all be killed

because that’s what you do with them,

and Mother Earth reigns?

Without her eyes that see at the top?

Without her plan

that gets a better man?

She’s evolvin’ you know,

and the cavemen on her now

can’t see past their own noses,

are limited thinkers in a limited field

that haven’t even discovered themselves yet.

They think they are separate in time.

Well Mr. Caveman,

do yah?

It’s all just a bunch of garbage, ain’t it,

conspiracy who-done-it,

meaning attributed to the whole?

It’s just all a waste.

Nothin’s done here.

Nothin’s bigger than us.

We are not on a globe that thinks and feels.

We see out our eyes,

not that globe,

or even larger fields.

Wham! Bam! Thank you ma’am!

we’re done.

Just finish us off,

or hate everybody and want to.

Like I said,

mom, dad, and I are worried about you.

You’re a big gun.

Now Mr. Caveman,

can you open your eyes and see

where we go to in consciousness?

Do you like study your dreams

and what they mean?

Done that with a group

over some long years?

A way to connect the dots from eye to eye.

Stumble upon that shared field,

at least in the restroom.

How could you know if you didn’t try?

And that mind of yours,

can you stop your thoughts?

Can you turn it on,

the state of emptiness,

and in that emptiness see the world arise

that sees all things

lock, stock, and barrel itself,

identifies with all?

How many people have seen that?

I have.

Now just go off and kill everybody

before you find the connections

you bad man.

Do you just want attention?

Are you just tryin’ to shock everybody?

Surely you can hold a child

and feel their worth.

Surely, surely,

you want to get out of caveman.

Report comment

Lovely

Report comment

Thank you.

Report comment

It is kinda late.

Just give me a second.

We meet each other in the morning

a field, a notion in the sky,

where we belong on earth together.

No time’s done.

In the poetry of this hour

I simply take your hand

Mr. Brother.

Can you see the revealing sky?

Thank you.

Report comment

This is so important. Thank you for writing this.

Report comment

Thank you for sharing your story/perspective, Jasmine. I agree, this is an important topic to discuss. As a fellow psych survivor, I can write my story as a hero’s journey story, that does not match any of the narratives you point out as the psych industries’ “narrative.”

“Exposition: Establish protagonist (main character), the afflicted,” would be me. A women who is supposed to be a “judge,” according to 40 hours of unbiased psychological career testing, an ethical banker’s daughter, a “tailor who sings with the Lord,” singing “that’s me in the spotlight losing my religion,” who hopes and prays we can all work our way towards healing … and eventually wisdom.

“Rising Action: Establish conflict: Symptom onset. Illness develops.” I will say distress, not “illness” developed, in my personal case … due to the worldwide distress of 9.11.2001 … which was my personal “Rising Action.”

“Climax: Protagonist confronts their obstacle, seeking professional help and receiving a clinical diagnosis.”

I did this, was a compliant patient, and was slowly weaned off of the majority of the psych drugs by my psychiatrist by 2005. Because once I’d stop seeing a pathological lying psychologist, my psychiatrist concluded I’d been misdiagnosed by that non-medically trained psychologist, which, of course, was true (a misdiagnosis of brain zaps, which weren’t known to the psych industries as a common withdrawal symptom of antidepressant discontinuation syndrome until 2005, but which was blatant malpractice according to the DSM-IV-TR at the time, and still should be).

“Falling Action: Protagonist diligently attends therapy and/or takes medication, and starts to get better.”

Well, I did “diligently attends therapy and/or takes medication.” But no, repeated anticholinergic toxidrome poisonings, made me much worse. However, I did start to get much better, as I was weaned off the anticholinergic toxidrome poisonings.

“Resolution: Full recovery! Victory!”

Well, not quite so simplistic … my “resolution”/”elixir” was getting off the psych drugs … but the withdrawal wasn’t at all easy, initially. And I did have to do a whole lot of research, and personal self healing. So I would say, I’m still on my healing journey, and will likely be my entire life, and I think I will spend my entire life working my way towards wisdom.

That’s not a bad thing, however I’m not certain it could be claimed to be “Full recovery! Victory!” either. But the Jungian psychologists do seem to see the wisdom of spending one’s life working their way towards wisdom. And hopefully, if we all collectively work our way towards wisdom, we can help heal humanity together. And that would be a true “Victory!”

Life’s a journey, a search for wisdom, for all of us.

Report comment

Ugh, I’m so glad you wrote this too—the brain zaps were very real. I got them from Cymbalta. What frustrated me most was how our concerns were brushed off as just symptoms of some half-invented pathology. Honestly, I’ve carried more trauma from being conditioned at a young age to believe I was “broken” than from any actual brokenness itself. They exploited that vulnerability for profit, then gaslit me when I brought up the black box warnings. I weaned off most of those meds in 2020—and I haven’t had a single suicidal thought since.

Report comment

“Honestly, I’ve carried more trauma from being conditioned at a young age to believe I was “broken” than from any actual brokenness itself.”

I feel the same. My family situation was “challenging”, to say the least, but the MHIC with its “meds” and misguided belief that grief is a “disorder” was far more traumatizing.

The MHIC seems to specialize in compounding whatever hell you may have already been through.

IMHO.

Report comment

Wow: this article packs alot in. I think there are at least 3 Phd thesis subjects here. Important stuff. But I object to the assumption, early on, that All mental illness, or every brain disorder (which I think is less judgemental) stems from trauma. In my experience surviving some aspects myself and or treating others, trauma is often the most compelling factor and in other cases trauma is nowhere evident. It seems we have mostly failed in humane or beneficial treatment either way.

Report comment

Yes, and I would add that the silencing and censoring of the vaccine injured, their families, and their loved ones may well be the social issue of our time.

Report comment

Ms. Marshall,

Well done.

Organizing these ‘lessons learned’ are so helpful when sorting out the (communal) past of the targeted and exploited …and identifying the eternal cynical & profitable patterns of behavior with the carefully adjusted, shifting language that propels the MHIC.

Their goals never change, only expand and harden.

I was able to parlay my own safety following a serious prescribing ‘error’, ‘negotiate’ a multi-year, doctor-guided withdrawal & written vacation of their ‘life-time’ bipolar 1/Arizona SMI diagnosis/certification…all because it occurred during an important ($) re-organization of the Arizona AHCCCS behavioral health provider’s C-suite paradigm , 2013-2016.

The result was that the existing CEO & newly minted (2013) CMO/VP quickly agreed to my terms…if I didn’t ‘introduce’ a legal representative/liability action.

They quickly jettisoned the MHIC iron-clad, no-exit/lifetime diagnoses and decade of drugging…sans any apologies that would infer responsibility for my independently (hospital) documented damage… first-year med-school, ‘garden variety’, often fatal Anaphylaxis.

Unfortunately for them, I had reported the 1st ADR, frantically requesting relief from a 2nd (!) Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome ‘event’…resulting in a different dosage of the same drug over my multiple objections…. ‘Take it….or decompensate, there’s the door’.

Anaphylaxis couldn’t be blamed on ME and ‘my worsening mental illness’, as the past decade of prescribed ‘treatment’ drug damage was characterized, which included cardiomyopathy… heart-failure.

A brain lesion had also manifested (Micrographia, duly reported/ignored) just before the Anaphylaxis.

My brain had endured enough & was frantic for relief.

The liability was All. On. Them.

They were aware of the mess THEY were in. Choices were offered, they accepted.

Ending the ‘treatment’ and changing my ‘lifetime diagnoses’ was financially, politically, & personally expedient.

MEDICAL SCIENCE was never referenced during our very polite meeting, discussing ‘our relationship’…and my future.

THEY made no pretense about immediately abandoning the APA, DSM, & Pharma dogma…if it threatened the long-game, the Big Picture (career & power) Paradigm of Arizona’s $2 billion dollar mental health budget…and their positions at the trough.

The CEO continues in 2025 to ‘manage’ & consult on a national level. The CMO/VP is still securely in place.

BTW, I turned down his texted request for a dinner date 2 months before I was finished withdrawing…I was ‘in his care’ when he sent it.

I kept ALL his texts.

I am deciding if they will be received and (1) assessed by the Arizona Medical Board appropriately….or (2) minimized as a non-issue…or (3) buried.

Yeah, it’s #3.

AZ Statutes described me as a “Vulnerable Adult”, under his direct care, drugged for the 2.5 years during withdrawal.

But psychiatric (sexual) coercion is such a troubling term.

And Stockholm Syndrome is real…but, with alot of effort, I’ve fixed that. AND moved 2500 miles away.

Report comment

Thank you, Jasmine, for covering this critical topic in your compelling narrative. The role of narratives surrounding mental health is, imo, critical mass. Here’s one example of why I think so:

A few years ago, I was eating my lunch in my car, when the screams of an angry women pierced my closed windows. I looked up to find a screaming woman who also appeared economically challenged. Fifty-more yards away, I saw an unkempt 5? year old girl with a filthy looking blanket over her shoulder, staring into a vacated store window. The women, I took as the girl’s mother, further screamed for the little girl to “get over here now”. I then watched as the little girl slowly walked towards her mother, her head down and completely devoid of any discernable emotion if not spirit. When the little girl got within 20 feet of the mother, the mother walked ahead as if the little girl was little more than an afterthought nuisance.

I declined calling the cops or other authorities, but I feared the mother’s behavior suggested comprehensive abysmal conditions at home. In that scenario, I feared the little girl was likely coming of age in a home that wasn’t providing the fundamental tenants of attachment, connection, attunement, and several other developmental “relationship conditions” that are absolutely essential to becoming a healthy and grounded human being. In that disastrous parental void, the little girls’ parents were unlikely to be providing her with the time and activities that foster a child’s cognitive and organizational development (being read to, played with, et al). And what if the father was as emotionally disconnected and abusive, save worse or absent (a not unlikely scenario)? A child from this “narrative”-that I and my 4 siblings and millions of other people share-will begin school (socialization) with emotional and cognitive deficits (we) have no narrative of. And if (perceived) behavioral or social challenges present-or are just enough of an inconvenience to the assembly line, children like this little girl will be hard pressed to escape a psychiatric diagnosis, a predominantly drug narrative systematically incentivized to grow “and solidify” over time. Each diagnosis-narrative, be it ADHD, ODD, bi-polar, BPD, anxiety disorder, etc., will scarcely glance at the child’s developmental history; because all the answers for the child cum adults’ difficulties and their respective solutions are prepackaged narratives that presume (demand) to speak for everyone and “everything”.

What haunts me about this little girl was is that it looked like she was staring at her reflection in this abandoned storefront window as if desperately waiting for it to reflect something back of herself that countered the “missing” and invasive reflections from her mother-and likely her entire “home life”? But what haunts me more are the prospects of this little girl as she gets older, that if the narcissistic psychological injuries that incur in such situations lead her into the MHIC-as is not unlikely, the help she (likely) receives from the MHIC will be about as an “embodied” and reflective a human relationship as the defunct corporation and its abandoned storefront windows had once been for her…

Lastly, I find Jasmines definition of trauma the single most accurate and therapeutically instructive definition of trauma I’ve either heard or read; hands down. My only quibble is that I believe that combining the word Subject with victim (i.e., subject/victim to victim/subject), suggests a reframing of both as verbs rather than nouns; a linguistic turn with a few promising implications, I think?

Report comment

Thank you, Jasmine. This is the personal narrative I’ve been waiting for.

Nothing’s more triggering/disempowering to me than psychiatric trauma being framed as benevolent while its survivors are portrayed as “The Bad Patient”.

It kind of reminds me of the way I felt seeing the movie “Gaslight” for the first time, only more triggering because psychiatric trauma is NOT a movie.

Report comment

CORRECTION: Yours is the personal narrative I’ve been waiting for.

Report comment

Not enough can be said about what Jasmine’s blog brings up, namely the narrative theft perpetrated by the Mental Health Industrial Complex.

The good intentions of those who build careers in it does not absolve them of this crime.

Report comment

The worst thing about a therapist’s or psychiatrist’s narrative about you is how often they take just one thing you say, or just one observation they make, and build a story around it—filling in the blanks themselves, often arriving at the wrong conclusions. And if they give you a chance to correct them, they usually don’t believe you. They’re so sure of themselves.

And most think they have the right to be intrusive—the worst violation of all…

Report comment

“When you romanticize or stigmatize what’s yours that’s narrative reclamation. But when survivors speak with nuance or pride, they’re accused of being irresponsible.”

That’s only half the problem with narrative reclamation. The other half is The Savior Narrative.

It seems many who work in the MHIC tend to romanticize the role they play, leading more than few to regard themselves as saviors, on some level; it’s the recipe for its grandiosity.

In other words, the MHIC doesn’t just romanticize its version of recovery, it romanticizes itself, making it the protagonist in its own myth.

It’s a hotbed of institutional narcissism.

Report comment

Here’s the role most psychiatrists seem to believe their patients are born to play:

COMPLIANT PATIENT FOREVERMORE

Report comment