In Part One of this article series, we reviewed the contemporary research into the links between psychosis, problematic family dynamics, and other forms of childhood trauma. After reviewing this research, we find that a very interesting and important question emerges: What do all of these have in common? In other words, is there some common denominator that all of these types of trauma and patterns of problematic family dynamics share, a single underlying factor that makes someone particularly vulnerable to experiencing a psychotic crisis? Indeed, I believe that there is.

In essence, I believe that in order to maintain wellbeing, we must ensure that certain core needs remain “well enough” met; and when this doesn’t happen, psychosis is likely to ensue. Furthermore, given the importance of our development throughout our earliest years in determining how well we do with regard to meeting these basic needs, and the importance of our family system in shaping our early development, we can connect the dots and say that problematic family dynamics can set the stage for our inability to adequately meet these basic needs, which in turn can lead to the vulnerability to experience a profound psychological crisis (i.e., psychosis). To better understand this, let’s start from the beginning.

As I’ve discussed at length in Rethinking Madness and elsewhere, we can see the very elaborate experience and understanding of our self and the world (our “personal paradigm”) as being akin to a tall skyscraper, with the very ground floor consisting of our most primal experience of self and the world and our most fundamental existential dilemma—the need to experience our “self” as a relatively secure and stable being living in a relatively secure and stable world, when the actual nature of the world and of our existence within it is not particularly stable and secure at all. Converging from numerous perspectives—spiritual, psychological, physical—is the recognition that the raw fabric of our world and of our experience is profoundly impermanent, interconnected and therefore fundamentally unitive—in other words, at the most basic levels, ultimately not consisting of discrete and permanent entities or selves. This is the basic fabric of existence to which many religions, spiritual traditions and even the current frontiers of Western science point to; and it is also these deepest waters of existence in which those who enter a psychotic process often find themselves desperately struggling not to drown.

Considering this “ground floor” existential dilemma from the perspective of a human being in the very early stages of development, we can say that as an infant emerges from the intra-uterine experience of relatively undifferentiated unity with the mother to the experience of a differentiated sense of self, he experiences an increasingly reified experience of both “self” and “other.” This experience in turn leads to the increasing importance of learning how to develop a relatively secure and enjoyable relationship between “self” and “other.” We can say that it is at this stage when the young person is developing the second floor of what will ultimately be the tall and elaborate skyscraper of his personal construct system of self and the world. I have referred to this second tier elsewhere as the “self/other dialectic,” or more appropriate to the context here, as the “autonomy/connection dialectic.”

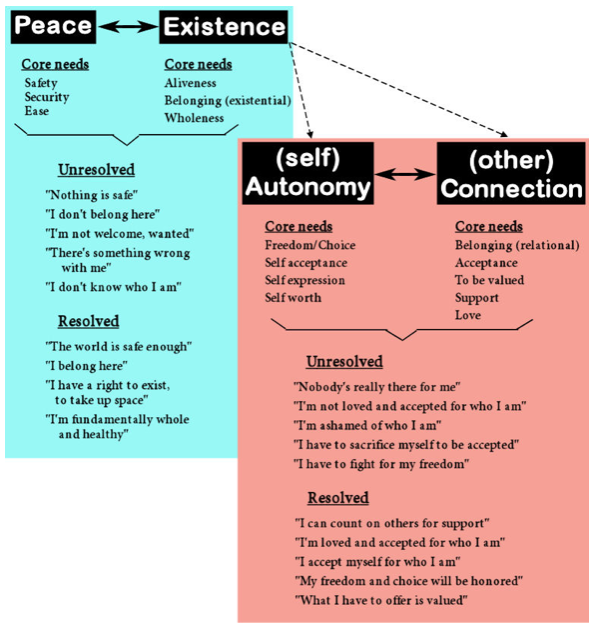

To summarize these two most foundational tiers of our development, then, we can say that as newborns emerging from the womb and into the world, we must first experience a “good enough” sense of safety, stability and a nurturing welcome (first tier needs) before having the capacity to properly venture into the risky business of differentiating into a unique “self” that is able to relate effectively with “others” (second tier needs). So generally speaking, safety (“It’s safe enough”) and belonging (“I belong here”; “My existence is welcomed”) can be seen as our most essential core needs, which are followed closely by our rapidly increasing needs for both autonomy and secure connection with others as our self/other differentiation increases (see Figure 1).

Focusing on this second tier, then, we can say that the autonomy/connection dialectic results from the universal human dilemma that, like it or not, we are profoundly relational beings. The nature and quality of our social relationships play a huge role in our wellbeing, and developing healthy, satisfying relations is generally very challenging for any of us, due in large part to this dilemma that we all share—one hand, we require a certain amount of healthy connection with others in order to survive and to ultimately thrive; and on the other hand, we also require a certain degree of autonomy (e.g., freedom, choice, personal power, self agency and a general sense of self worth). So the dilemma lies in the inherent difficulty of trying to develop healthy relationships with others in which we experience both secure enough nourishing connection and intimacy and also enough freedom and autonomy so that we can tolerate (and hopefully enjoy!) our existence; hence the term “autonomy/connection dialectic.”

The other key component of this term is “dialectic,” which is derived from the Hegelian notion of two apparently contradictory elements (the “thesis” and the “antithesis”) coming together to form a unified whole (the “synthesis”). So the autonomy/connection dialectic refers to the fact that on one hand, it can be challenging to find a balance between two seemingly contradictory needs, or drives—autonomy and connection—but on the other hand, we find that it’s possible to develop in such a way that these actually become mutually reinforcing—the more we develop a sense of genuine comfort and security with our autonomy and self worth, the more likely it is that we will feel at ease while connecting with others, and vice versa. So we find that it is possible to arrive at a state of “synthesis” or “resolution” in which we experience wholesome and nourishing relationships in which both autonomy and connection are satisfyingly met (see Figure 1).

While this dilemma of the autonomy/connection dialectic shows up within all of our social relationships—be they with siblings, friends, romantic partners, colleagues or other peers—it first shows up in our relationship with our parents (or other primary caretakers, which I’ll collectively refer to as simply “parents”). And not only does it merely show up in our relationship with our parents, but the degree of success we experience with regard to resolving this dilemma within these primary relationships powerfully influences how successful we are in developing into a mature, relatively happy human being. These first relationships form the foundations for the way that we feel and behave in all subsequent relationships with others, and also how we relate with ourselves.

This process of developing a healthy, wholesome relationship with ourselves, and the capacity to experience such relationships with others, is sometimes referred to as “individuation,” a term popularized by transpersonal psychologist Carl Jung, and a concept that has been further explored and expanded upon within Attachment Theory, as first developed by John Bowlby in the late 50s and 60s (Bowlby, 1969). To put this term into the context I’m presenting here, we can say that “individuation” essentially refers to our developing in such a way that we experience a “good enough” resolution of the autonomy/connection dialectic (which is in turn dependent upon our resolution of the more primal peace/existence dialectic), which then gives us the capacity to experience healthy, nourishing relationships with ourselves and others.

As we develop as children, while of course our entire childhood influences our process of individuation, it does appear that there are two particularly critical periods in this regard. The first period is more or less our first 2-3 years of life, in which we first develop attachment styles that are likely to remain relatively robust throughout our lives. These refer to habitual patterns of relating to others, and can be seen as corresponding directly to the autonomy/connection dialectic. During these very early years of our life, the way that our parents behave and relate to us profoundly shapes the personal lens through which we make sense of ourselves and others. If we experience an adequate degree of both secure connection and autonomy/validation, then the message that becomes imprinted deeply within our being is, “I’m welcome here, I can count on being supported, and I am loved and valued for who I am.” This experience of the world as generally nourishing and supportive is associated with the development of what is referred to within attachment theory as a secure attachment style, and can essentially be seen as indicating that the child has so far been successful in achieving a relatively sustainable and healthy resolution to the autonomy/connection dialectic, at least at this early stage of development.

If our connection and/or autonomy needs are not adequately met during these early years, then according to attachment theory, we are likely to develop an insecure attachment style, a problematic relational style that is generally recognized as veering into one of three extreme relational directions. On one extreme, we become excessively fearful and avoidant of intimate contact, so experience an excessive fear of connection (what I like to refer to as engulfment anxiety, as in a fear of being “engulfed” or overwhelmed by the other), and this is typically referred to as an avoidant insecure attachment style. On the other extreme, we become excessively clingy, so experience an excessive fear of autonomy (what I like to refer to as isolation anxiety or abandonment anxiety), and this is typically referred to as an ambivalent insecure attachment style. Finally, in the most extreme cases, we find that a person can swing radically from one of these extremes to the other, or even experience them both simultaneously (an excessive fear of both autonomy and connection), what is often referred to as a disorganized insecure attachment style.

When a person develops an insecure attachment style during this early stage of development, certain limiting core beliefs become imprinted deeply within one’s being, such as: “I’m not welcome here,” “Nobody cares about me,” or “I’ll be cared for, but only if I give up my freedom or suppress my authentic self.” And when reflecting upon the autonomy/connection dialectic, it’s easy to see how such beliefs, which initially emerged out of a failure to experience successful resolution with regard to this dialectic at this early stage, are then likely to interfere with the individual’s ability to achieve successful resolution of this dialectic during the second critical stage of this process occurring much later, in late adolescence (discussed below).

Research into links between attachment styles and psychosis has only recently begun to be carried out; however, we are already finding strong correlations between early insecure attachment styles and the later development of psychosis (Berry, Barrowclough & Wearden, 2007; Read & Gumley, 2008; Williams, 2011). I think to fully grasp the significance of this link it will help to bridge my own exploration of the fundamental existential and relational dialectics (the peace/existence and autonomy/connection dialectics, respectively) with Gregory Bateson’s work on the links between double binds and psychosis. Recall that Bateson describes a double bind essentially as that which occurs when we find ourselves torn between two injunctions that are placed in mutual opposition, so that following one injunction is likely to lead to punishment associated with betraying the other; and yet there is the possibility of finding a resolution to this dilemma, by either finding a way to shift from the impossible “either/or” dichotomy to a “both/and” solution and/or by transcending the system altogether. Closely related to this, I see the peace/existence and autonomy/connection dialectics as essentially representing such double binds that have been imposed upon us by our very existence, with our healthy development requiring that we find a way to transcend the possibility of becoming caught indefinitely in an impossible “either/or” dichotomy with regard to these, and to instead arrive at a workable “both/and” solution (i.e., developing a belief system and life strategy that allows us to have both enough peace and also enough meaningful/sustainable existence, and both enough autonomy and also enough nourishing connection with others). Figure 1 shows some common core beliefs likely to be associated with these dialectics being unresolved vs. resolved.

So using this framework, we can say that the degree of relational security we have achieved as indicated by our particular attachment style essentially represents the degree to which we have experienced resolution of these two core double binds that are inherent within our very existence. Bridging the works of Bateson, attachment theory, and my own explorations, then, we can say that while we all share these core existential dialectics/double binds, the family and social dynamics within which we are raised profoundly affects our ability to achieve a “good enough” resolution to these so that we may live enjoyable lives.

The second particularly critical period with regard to healthy individuation occurs in late adolescence and early adulthood. It is at this stage that healthy development requires that we undergo a transition in our primary attachment figures, from our parent(s), who have likely been our primary attachment figures up until this point, to a romantic partner, with a relatively secure and longstanding romantic relationship generally considered the most natural and optimal developmental aim in this regard. This transition is difficult for most children and parents to various degrees, but for some children and parents, the difficulty of this stage of individuation can be completely overwhelming, and therefore pave the way to the development of psychosis. I believe that this is why the large majority of people who experience psychosis first do so during this particular developmental stage—between mid/late adolescence and early adulthood. Some people do experience their first onset of psychosis much later in life, but from what I’ve seen in the literature and in my own clinical experience, I would say that the majority of these cases are still closely related to a problematic relationship with a primary attachment figure, but that the primary attachment figure is often a romantic partner rather than a parent. Furthermore, I suspect that in the majority of even these cases, the person likely had some pre-existing vulnerability as a result of earlier attachment issues stemming from childhood.

So why is this particular stage of individuation—that of young adulthood—so difficult for some people, children and parents alike, and why can it be so difficult as to sometimes lead to psychosis? In order to answer these questions, it will help to contemplate this stage of individuation as directly experienced from the two different perspective—that of the child and that of the parent:

The child’s perspective. For those of us who have already passed into adulthood, it will help to take a moment to reflect upon our own transition from childhood into adulthood. Most of us will be able to recall several very powerful drives that greatly influenced our behavior during this time. There is usually the drive to distance ourselves from our parents, and to spend an increasing amount of time with peers, including both friends and romantic partners. There is also the drive to come out from under the authority of our parents and to experience as much freedom and autonomy as possible. So in general we can see these as healthy drives pushing/pulling us towards mature adulthood, in which we make the transition to more equal footing in our relationship with our parents—ideally coming to see them more as supportive close friends than as authority figures—and from having our parents as our primary attachment figures to having a romantic partner take on that role.

But along with this pull we feel towards increasing autonomy, most of us also experience some fear associated with this. Will I be able to make it out there in the world without the support of my parents? Can I actually handle the self-responsibility that goes along with being an autonomous adult, taking full responsibility for all of my own actions? Will I be able to develop enough nourishment and satisfaction within my relationships with friends and romantic partners?

With some honest reflection, I think that all of us who have gone through this transition into adulthood should be able to recognize this dilemma—the ambivalence of wanting more freedom and autonomy on one hand, and on the other hand, feeling some degree of insecurity with regard to our ability to really handle these. And closely related to this is usually the concern associated with our ability to continue adequately meeting our connection and belonging needs as we transition away from the direct care of our parents and more fully into the fold of peers and lovers. Some of us struggle with this dilemma much more than others, and the reasons for this can be numerous, but it is clear that the nature of our relationship with our parents, both prior to and during this transition, plays a major role in how difficult this transition will be for us.

When this transition fails, the person essentially fails to achieve healthy individuation (i.e., to successfully resolve the autonomy/connection dialectic), and certain harmful core beliefs associated with this develop or are reinforced, such as: “There’s something wrong with me,” “I won’t be able to find someone who will love me for who I am,” “I have to choose between being authentic and being loved,” and “I can’t handle it out there.” The person then feels trapped in a very painful dilemma: on one hand, the experience of overwhelming engulfment by the parent(s) to whom they continue to feel so dependent upon, which is often associated with powerful feelings of anger and resentment towards them as a result of this; and on the other hand, the overwhelming fear of isolation and loneliness should they fail to develop secure and nourishing relations with others upon leaving home. And further stacked upon these feelings is often deep shame and even self loathing as a result of finding oneself so stuck within such a predicament.

This predicament, with so many painful feelings that go right to the core, has the potential to be powerful enough to push anyone over the edge, though we may each differ in just how much we can tolerate before this tipping point is reached. And unfortunately, many parents, wittingly or unwittingly, often directly exacerbate this predicament and increase the likelihood of the ultimate failure of their child’s individuation, due to their own ambivalent feelings.

The parent’s perspective. As any parent knows, raising a child requires an enormous whole-being commitment typically lasting at least two decades, often entailing the sacrifice of deep personal ambitions in the process. This great sacrifice combined with the very natural tendency to become deeply attached to one’s children can make it very difficult to let them go when they come of age. To devote so many years and resources towards the life of this being, and then to simply let them go free into an unpredictable and frankly dangerous world . . . this is no easy task for any loving parent, and yet if we want our children to experience the fullness of mature adulthood, this is exactly what is called for. It’s no wonder that many parents really struggle with this, and in spite of what may be the best of intentions, may directly undermine their child’s individuation process.

Just as in the case of the child, the parent may find that she is harboring or reinforcing certain personal core beliefs that ultimately cause more harm than benefit to their child’s individuation process, such as: “There’s something wrong with my child,” “He’s not ready to handle the world,” “I have to protect her from the world,” “I have to protect him from himself.” And just as in the case of the child, the parent may struggle with very powerful and ambivalent feelings associated with this dilemma. On one hand, the parent probably really does want to see their child transition to an independent and enjoyable life, and may even genuinely desire a bit more personal space and freedom for themselves; and on the other hand, they may also fear for their child’s safety and/or fear becoming overwhelmed by their own feelings of loneliness and meaninglessness once the child leaves (the so called empty nest syndrome). While it’s natural for most parents to struggle with such mixed feelings, if these feelings are powerful enough and not adequately checked by the parent, they are likely to only reinforce their child’s own ambivalence about individuation and increase the likelihood of failure.

In Part Three, by taking guidance from the research we reviewed in Part One and the theoretical framework presented here in Part Two, we’ll look at practical ways that families and individuals struggling with such extreme states of mind can work towards greater harmony and wellness.

* * * * *

References:

(for all three parts of the article)

Bakhtin, M. (1984). Problems of Dostojevskij’s poetics. Theory and history of literature: Vol. 8. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

Bateson, G., D. Jackson, D., Haley, J., & Weakland, J. (1956). Toward a Theory of Schizophrenia. Behavioural Science 1, pp. 251-54.

Baumrind, D. (1989). Rearing competent children. In W. Damon (Ed.), Child development Today and Tomorrow. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Berry, K., Barrowclough, C., & Wearden, A. (2007). A review of the role of attachment style in psychosis: Unexplored issues and questions for further research. Clinical Psychology Review, 27(4):458-475.

Bola, J., & Mosher, L. (2003). Treatment of acute psychosis without neuroleptics: Two-year outcomes from the Soteria project. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 191(4), 219-229. doi:10.1097/00005053-200304000-00002

Bowen, M. (1960) A family concept of schizophrenia IN D.D. Jackson (Ed.) The Etiology of Schizophenia. New York: Basic Books.

Bowen, M. (1993). Family therapy in clinical practice. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and Loss, 3 vols. London: Hogarth, 75.

Brown, G.W., Bone, M., Palison, B. & Wing, J.K. (1966) Schizophrenia and Social Care. London: OUP.

Fromm-Reichmann, F. (1948) Notes on the development of treatment of schizophrenics by psychoanalysis and psychotherapy. Psychiatry, 11, 263-273.

Furnham, A., & Cheng, H. (2000). Perceived parental behavior, self-esteem, and happiness. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 34(10, 463-470.

Galambos, . L. (1992). Parent-adolescent relations. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 1, 146-149.

Goldstein, M. The UCLA High-Risk Project. Schizophrenia Bulletin 1987; 13(3):505-514.

Greenberg. J. (1964). I never promised you a rose garden. Chicago; Signet.

Janssen I, Krabbendam L, Bak M, Hanssen M, Vollebergh W, de Graaf R, et al. Childhood abuse as a risk factor for psychotic experiences. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 2004;109(1):38-45.

Karen, R. K. (1994). Becoming attached: First relationships and how they shape our capacity to love. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Laing, R.D. (1960) The divided self: An existential study in sanity and madness. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Laing, R.D. and Esterson, A. (1964) Sanity, madness and the family. London: Penguin Books.

Laing, R.D. (1967). The politics of experience. New York: Pantheon Books.

Miklowitz, J.P. (1985) Family interactions and illness outcomes in bipolar and schizophrenic patients. Unpublished PhD thesis, UCLA.

Mosher, L. R. (1999). Soteria and other alternatives to acute psychiatric hospitalization: A personal and professional review. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 187, 142-149.

Napier, A.Y. & Whitaker, C.A. (1978; 1988). The Family Crucible. New York: Harper & Row.

Neufeld, G., & Mate, G. (2014). Hold on to your kids: Why parents need to matter more than peers. New York: Ballantine Books.

Norton, J. P. (1982) Expressed Emotion, affective style, voice tone and communication deviance as predictors of offspring schizophrenic spectrum disorders. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, UCLA.

Read, J. (2004). Poverty, ethnicity and gender. In J. Read, L. R. Mosher, & R. P. Bentall, (Eds.), Models of madness: Psychological, social and biological approaches to schizophrenia(pp. 161-194). New York: Routledge.

Read, J., Fink, P., Rudegeair, T., Felitti, V., & Whitfield, C. (2008). Child maltreatment and psychosis: a return to a genuinely integrated bio-psycho-social model. Clinical Schizophrenia & Related Psychoses, 2(3), 235-254.

Read, J., & Gumley, A. (2008). Can attachment theory help explain the relationship between childhood adversity and psychosis? Attachment—New Directions in Psychotherapy and Relational Psychoanalysis, 2(1):1-35.

Resnick, M. D., Bearman, P. S., Blum, R. W., Bauman, K. E., Harris, K. M., Jones, J., … & Udry, J. R. (1997). Protecting adolescents from harm: findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. Jama, 278(10), 823-832.

Seikkula, J., Aaltonen, J., Alakare, B., Haarakangas, K., Keränen, J., & Lehtinen, K. (2006). Five-year experience of first-episode nonaffective psychosis in open-dialogue approach: Treatment principles, follow-up outcomes, and two case studies. Psychotherapy Research, 16(2), 214-228. doi: 10.1080/10503300500268490.

Seikkula, J., & Olson, M. E. (2003). The open dialogue approach to acute psychosis: Its poetics and micropolitics. Family process, 42(3), 403-418.

Selvini-Palazzoli, M., Boscolo, L., Cecchin, G., (1978). Paradox and counterparadox. New York: Jason Aronson.

Shelvin M, Houstin J, Dorahy M, Adamson G. Cumulative traumas and psychosis: an analysis of the National Comorbidity Survey and the British Psychiatric Morbidity Survey. Schizophr Bull 2008;34(1):193-99.

Siegel, D., & Hartzell, M. (2003). Parenting from the inside out: How a deeper self-understanding can help you raise children who thrive. New York: Tarcher/Penguin.

Siegel, D., & Payne, T. (2014). No-drama discipline: The whole-brain way to calm the chaos and nurture your child’s developing mind. London: Scribe.

Whitaker, R. (2010). Anatomy of an epidemic: Magic bullets, psychiatric drugs, and the astonishing rise of mental illness in America. New York, NY: Crown Publishers.

Williams, P. (2011). A multiple-case study exploring personal paradigm shifts throughout the psychotic process, from onset to full recovery. (Doctoral dissertation, Saybrook Graduate School and Research Center, 2011). Retrieved from http://gradworks.umi.com/34/54/3454336.html

Williams, P. (2012). Rethinking madness: Towards a paradigm shift in our understanding and treatment of psychosis. San Francisco: Sky’s Edge Publishing.

Wynne, L.C., Ryckoff, I.M., Day, J. & Hirsch, S.I. (1958) Pseudomutuality in the family relations of schizophrenics. Psychiatry, 21: 205-220.

I appreciate your orientation away from drugs and the prominent psychiatric myths we all hate on this site, but your approach is doomed in our current society. Love and care, harmony? In a nation whose top officials say things like, “We droned a 16 year old boy to preempt his future danger to us. Yeah, he should have chosen a different father if he didn’t want to be assassinated.” A paraphrase, but you’ll find it’s accurate in tone and content. We might as well live in 30s Germany. Would you have had much chance of implementing your ideas in that milieu?

Reform of this society must be a priority and any work at reforming psychiatry has to take that into consideration.

Report comment

1930s Germany had already elected Hitler as leader. We haven’t elected Donald Trump yet 🙂

30s Germany later became a country where psychoanalytic-developmental thinking about emotional problems flourished, allowing many people to receive analysis and therapy in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s. Heinz Kohut and the followers of Jung and Freud lived and worked in post-war Germany, Austria, and Switzerland.

So maybe America will really change for the better, hard as it may be to imagine now.

Citing one quote from a “top official” (and where is the source anyway?) does not accurately represent the tone and content of all officials in America. Some of them ignorantly support a reductionist model of emotional problems, but not all; and most are simply ignorant or uninterested.

MadInAmerica’s existence, and the increasing public criticism of mainstream psychiatric diagnosing and drugging over the past several years, represent small positive steps and reasons to have hope for change.

Report comment

Hi

Myself, I think that if things don’t work out right at the start that it can still be possible to put things right later on. Though a good upbringing would be the best one.

Report comment

Hi Ann,

Excellent point–how do we develop harmonious, healthy families within these broader social systems that are so deeply troubled and broken? I couldn’t agree more with the importance of not losing sight of the broader social systems. Although in this article I am focusing on the family, I’m also a strong critic of the broader health system:

see http://www.madinamerica.com/2013/05/the-mental-illness-paradigm-itself-an-illness-that-is-out-of-control/

…and contemporary human society in general:

see http://www.madinamerica.com/2015/06/can-madness-save-the-world/

Thanks for not letting us lose sight of the bigger picture!

Paris Williams

Report comment

Paris,

This is another very good article. Your vision of human emotional development is basically the psychoanalytic model I had been referencing in the last article. This view includes the fundamental need for good, nurturing “objects” (other people), the need for a secure symbiotic relationship leading to a gradually greater differentiation and then individuation from others, the importance of trauma and fear in causing a developmental arrest and a frozenness/regression to a primitive relational stage… these are the things writers like Bowlby, Ronald Fairbairn, Melanie Klein, Harry Guntrip, James Masterson, Otto Kernberg wrote about.

I have written an article very analogous to this one and would like to share it:

https://bpdtransformation.wordpress.com/2015/10/19/27-the-kleinian-approach-to-understanding-and-healing-borderline-mental-states/

This is the Kleinian / psychoanalytic approach to extreme states; I am mostly discussing “borderline states”, but these states of mind develop from the same relational failures that cause psychotic states; borderline states could be viewed as the higher more functional segment of the continuum of psychotic states. Borderline states could be viewed as a minor form of psychosis in which a person has somewhat more success in relationships / functioning than a frank psychosis, but still struggles greatly with intimacy and autonomy.

This chart puts into a developmental picture the processes of increasing integration that you talked about:

https://bpdtransformation.files.wordpress.com/2015/10/parallelpsychmodels1.png

Paris, your thinking is right on and it is no surprise to me that it follows a developmental model that many psychoanalytic writers have previously written about. I always felt that this model, which emphasizes the primacy of positive relatedness between the child and caretaking figures, was intuitive and right-on. It is a great shame that fear of blaming parents and the need to profit by misleading people into thinking that developmental-relational problems are brain diseases have caused many, many people to be unable to understand an obvious point: most psychoses are failures of emotional development, i.e. failures of parents and peers to adequately support the developing person.

Report comment

Hi BPD Transformation,

I’ve only had a chance to peruse your article, but I’m impressed and intrigued by your work of integrating these various models, and I look forward to looking at your article more closely. It’s always a pleasure to come across someone like yourself who enjoys such integrative exploration. This reminds me of one of my favorite stories is of the blind men who come across an elephant for the first time. One comes across the tail and declares, “Ahh, an elephant is like a brush!” Another comes across a leg and declares, “No, it’s like tree trunk!” Another comes across the trunk and says, “No, an elephant is like a snake!” Of course they’re all “seeing” the same elephant, but each only seeing one small truth and missing the bigger truth; so by being open to multiple perspectives, we’re more likely to become aware of the shared universal “truths” to which they all point.

I’m really enjoying and appreciating your engagement with these articles.

Paris Williams

Report comment

Paris,

I like this story about the elephant. Although, if I elaborated upon the story, I would say that biological psychiatrists are not even feeling up the same elephant; if most people are trying to understand the same “elephant” on Earth, they are on some extrasolar planet touching one of the horrendous Aliens with which Lieutenant Ripley used to do battle. That’s how bizarre and detached from real people’s experiences their writing about diagnoses and psychiatric treatment sometimes sounds to me.

I have one criticism to make of your work. I think sometimes you are focused a bit too much on the “benefits” or “transformative potential” of extreme states. Some psychiatrists criticized the BPS report on Psychosis, and work like yours, by saying that it trivializes psychosis. I think that this charge is largely incorrect and motivated by their fear that their own conceptual model of psychosis as a brain disease will be exposed as completely baseless and harmful. But there may be a small kernel of reality in this criticism.

I think it’s important to emphasize that most experiences of psychosis are extremely painful and overwhelming, filled with annihilation anxiety, terror, rage, confusion, dread, etc. As Volkan wrote about it, the experience of completely losing one’s previously cohesive sense of self and descending into psychosis is a terrifying transition felt to be worse than death, as reported by his clients. Often psychosis is not at all positive… and as for transformation, it is often not really the psychotic experience that is transformative, but rather the helping relationships that provide the “salvation” from the psychotic experience, to use Fairbairn’s term for what the persecuted person needed.

If you know the writer James Grotstein, he conceptualized psychotic conditions as “black hole states” in which similar psychological principles to actual physical black holes predominate… i.e. the lack of boundaries, the sense of immense psychic pressure, of being swallowed up or engulfed, of time and space ceasing to have meaning… obviously these are very bad things when one’s experience becomes warped away from consensus experience in a loosely analogous way to how something is crushed when it enters a black hole. I believe he also wrote about the isolation and hopelessness of some psychotic states as being like “darkness on the face of the deep”, a very evocative description…

as Jeffrey Seinfeld said, the severely and chronically psychotic person experiences “The Death of God (God meaning the “object” or the mother/other preson, i.e. the psychological destruction of other people’s normal holding functions), and black hole depression, and ontological insecurity (the sense of a severe fragility in one’s core state of being, as R.D. Laing described) “.

I give these evocative quotes to bring home to other readers who may not have experienced them personally how severely overwhelming psychotic states can be and why people will do anything to avoid these catastrophic mental states. I favor emphasizing how difficult and painful psychotic states are, because I think psychoses are on balance the result of (far) more bad than good experiences. I think transformation and healing can come out of them, but given that psychoses are mainly caused by severe neglect, abuse, and trauma, the psychoses themselves (the results of adverse psychosocial factors) are not causing the transformation… rather, the activation and meeting of normal developmental needs for connection and love are what leads to transformation and salvation. Just my opinion.

By emphasizing the dark side of psychosis more heavily, but noting that it is still transformable, I think we can respond more strongly to biological psychiatric critics who assert that groups like the British Psychological Society are “trivializing psychosis” by (over)focusing on its lighter aspects. I try to emphasize a similar theme in my writing about borderline states by emphasizing how difficult they are without reifying them.

Report comment

One thing I find fascinating is how the same experience can be terrifying or awesomely good depending on how it is interpreted.

The same loss of meaning, lack of boundaries, dissolution of self and the world that can be seen as so terrifying and hopelessness inducing to some, can also be experienced as liberation and as the divine by others, or by the same person at other times. Isabel Clarke does a good job of writing about this, see my review at http://recoveryfromschizophrenia.org/2011/07/madness-and-mystery/

So while I am all for empathizing with people that they may be experiencing something as truly awful, I’m very wary of viewing the awfulness as objective – because that cuts off the possibility that the person can learn to interpret it differently.

Or, as I’ve put it elsewhere, if we go too far in trying to avoid “trivializing” or “romanticizing” psychosis, then we instead “awfulize” it, and that keeps people trapped, because now they think something truly awful is happening to them, and this makes it less likely they can become open to the possibility that they are simply experiencing a dimension of reality or a perspective on reality (and the perspective in which “meaning” and “self” is seen as illusion is useful in some ways even as it is threatening in other ways.)

Report comment

Thank, you, Ron.

Report comment

Thanks, BPD Transformation and Ron, for your comments.

BPD…, thanks for expressing your critique, when you said: “I have one criticism to make of your work. I think sometimes you are focused a bit too much on the “benefits” or “transformative potential” of extreme states.” (…and Ron, I resonate with your response that it’s helpful to acknowledge the subjective response to a particular experience).

I suppose if you have only read my articles, I can understand how you may perceive my work in this light, as I do tend to emphasize the potential for positive transformation as a result of going through such experiences, mostly because I want to counter the all-too-pervasive tendency within mainstream discourse to fixate on the “pathological” aspect of such experiences and generally deny the possibility for any personal growth and healing from them at all. I do, however, make a point to regularly emphasize that such a process is extremely risky and haphazard, with a wholesome resolution definitely not being guaranteed, and with the experience of profound distress and overwhelm nearly ubiquitous within such experiences.

Also, if you’ve read my book about this, Rethinking Madness, you’ll see that I devoted much of it to formulating my thesis (based on similar works of others) that what we often call “psychosis” is directly related to a profound “self renewal” process, typically requiring that one has to pass through the profound terror associated with “death” and “disintegration of the self,” a terror nearly impossible to describe to those who haven’t experienced this, as you suggest. All six “case studies” included within it clearly revealed that everyone experienced tremendous suffering, distress and even overwhelming terror at times associated with their own processes, though they eventually came to appreciate the tremendous personal growth and healing that ultimately occurred for them as a result of having gone through this.

In my own “psychotic process,” when I try to describe what it was like to others, often the closest I can come is to say that it was like a terrifying nightmare from which I couldn’t awake, going on day after day, month after month, with my only really feeling as though I’ve fully awoken from the nightmare after several years; or even somewhat more accurately, for those who’ve had the misfortune to experience the terror and chaos of a “bad trip” on LSD, that it was like falling into such a “bad trip,” and then not being able to “snap out of it” for many months (years really), though the “trip” was interspesed with (all too rare) moments of profound expansiveness, equanimity and unitive experiences.

If you’re interested to hear a bit more about my own process, I’ve included bits of it within this guidebook I’ve compiled on “Working with Spiritual/Existential Crisis”:

http://www.rethinkingmadness.com/download/i/mark_dl/u/4007924736/4622658684/Working%20with%20Spiritual%20Crisis.pdf

Best regards,

Paris

Report comment

Thanks, Paris and Ron. These are interesting thoughts.

Paris, I did read Rethinking Madness from cover to cover when it first came out. However, I did not remember some of it since it’s been a while since 2012 (almost 4 years now!). Now that you remind me I see a bit more the balance of how you wrote it.

Report comment

In my search into schizophrenia due to my sons recent diagnosis, I am thankful to come across your article, as well as post comments, in this case the idea of “renewal.” All along while we have been witnessing my 25 year old adult sons delve into hard drugs and subsequent or perhaps precursing, psychosis. I have been holding on to this idea of transformation, a transformation that he covered up with drugs, and one that as he is now off of hard drugs, has begun to cause a new set of complications. Complications in form of anger, disorganized thinking and irrational interactions along with his need to feel safe. I am left wondering if, as for you, Paris, all will be well once

this all settles down. In the meantime, he is on meds, has the support and love of both parents, and a mother on a mission to become both familiar with alternatives as well as find the support of a community of like minded individuals. This site is the breath of fresh air for which I was searching.

Regards,

Mariska

Report comment

Hi Paris,

Thanks for next instalment. I find your writing very interesting. You’re very well prepared, I need to read you’re writing again and again to take it in completely (I always thought that parents invariably skrewed a child up one way or another – but that children often turned themselves out okay by default).

Report comment

Hi Fiachra,

I’m glad to hear you’re enjoying my articles (I realize that I am cramming a lot into these).

Your comment reminds me of something I read from one teacher (I believe it was the Buddhist teacher/writer/psychologist, Jack Kornfield), which said something to the effect of, “We spend the first few years of our lives getting banged up, and the rest of our lives trying to recover.” I think there’s something to that–and I’ve never ceased to be amazed by human resiliency, as you also allude to.

Best wishes,

Paris

Report comment

Thanks Paris,

I’ll read over and over the articles – they’re very informative.

Report comment

Hi Paris,

Thanks again Paris for sharing your thorough and compelling conceptualization of family dynamics and the development of psychosis.

I am wondering how you would predict young people who have difficulties associated with (mild) “autism” would vary from others without this challenge, according to your theory? It seems that having developmental challenges could add tremendous stress for young adults and that for them the world may be confusing, unwelcoming and unsafe in many ways, not only because of family dynamics and other factors, but because living in society, individuating and connecting to others is much more difficult for them.

My guess is that developmental difficulties would make the tasks of individuation and autonomy more complex and may increase the chances for the development of psychosis or a related experience. Feeling safe and having a sense of belonging are much more challenging for young people who find connecting to others so arduous.

Thanks for your work.

Report comment

Hi Truth in Psychiatry,

Great questions/comments. As someone who tends to look for the universal existential “truths”/dilemmas within human experience, I would say that regardless of a particular diagnosis of a person’s distress or disability, and even regardless of the particular etiology, I believe that ultimately, we all struggle with the same core existential and relational dilemmas/dialectics (as discussed in this article), although certain circumstances are likely to make it more difficult for some than others to experience “good enough” resolution to these.

“Autism” is a very controversial term, not unlike “schizophrenia” in many ways, and though it’s not an area that I have much experience with, I suspect that your points you’re making here are right on. If a person develops certain limitations (especially social limitations, such as what we often see in a person with the “autism” diagnosis), then I agree with you that it stands to reason that they may well struggle with these core dialectics more than the average person. But I think it’s also important not to lose sight of the resilience and core organismic wisdom of the human spirit–as is said, “where there’s a will, there’s a way.”

Best regards,

Paris

Report comment

Hi Paris,

Thanks for your response. I agree with your theory about how early attachment and later individuation probably plays a pivotal role in the development of psychosis for some people.

However, I encourage you to be careful about making comparisons or overgeneralizing about what I believe are both very broad and very different types of difficulties – “schizophrenia” and “autism.” I see these two labels as similar in that they are both labels that may reflect conditions that are diverse with varying causes and treatments. I also share your concern about the reductionism associated with the disease model of mental health conditions and think that trauma and attachment difficulties are often a big cause of emotional suffering.

I also shared in a previous post that my son, who has what has been called mild autism experienced psychosis and came through it with no neuroleptics or hospitalizations. Instead, our family used an Open Dialogue informed approach and advice and support from all of our trusted friends, including you to move through this difficult time. Your advice about honoring my son’s existential questions and his need to individuate were very helpful. You reminded us, his parents to support his individuation. Through Open Dialogue many family dynamics were put on the table and addressed.

Yet, I believe that his emotional pain and psychosis also related to his trauma and extra challenges in life which relate to what has been called his “autism.” As a child, he frequently misunderstood social situations, retreated into his own world to cope, experienced bullying and overwhelming feelings of inadequacy in a world that often rejected his differences. He continues to work to individuate and have all the things his brothers have, a girlfriend, a full social life, meaning and independence. None of these things come easy for him.

I would be very careful about comparing the label of autism to the label of schizophrenia, although I think both may be invalid. Schizophrenia may represent a large group of experiences related to adjustment and finding one’s place in the world as you suggest. However, from all of my heartfelt reading and research on “autism,” I have come to believe that it may be explained on one end with individual differences and eccentricities and on the rest of the continuum as neurological damage, often dating back to prenatal exposure to toxins. I am pasting an article from MIA which shows one such possibility. There are many more. The medication I took for 5 months for severe morning sickness with my son, Phenergan, is a type of neuroleptic known to cause neurological damage in fetuses. Had I known this at the time, I would have done anything to avoid this risk, something I was able to do with my later two pregnancies. Thus, research is showing more and more how toxins, including the skyrocketing use of pharmaceuticals during pregnancy probably account for much neurological damage and the dramatic increase in autism rates.

While we explore the psychodynamic roots of mental health conditions and extreme experiences, I think we should remain humble to the very real differences in possible causes of various conditions. We must be very careful not to suggest that parenting causes conditions that likely have a basis in exposure to toxins, such as autism. Antidepressants, neuroleptics and other drugs, including Thalidomide, used during pregnancy (see article below) have all been implicated in the development of autism.

Yes, each person must grow and does face the same challenges to individuate and build a life. Yet, having a condition similar to what we now label autism makes things much harder for individuals and their families and is not necessarily related to attachment issues.

Thanks again for your work Paris

Report comment

Here is the article I mentioned, https://www.madinamerica.com/2014/09/autism-deficit-super-sensitivity/

Report comment

Hi Truth in Psychiatry,

Thanks for adding more clarity to your situation, and for sharing more about your family’s difficulties.

You said some things that make me realize I should have been more clear about my comment.

You said: “We must be very careful not to suggest that parenting causes conditions that likely have a basis in exposure to toxins, such as autism.”

I think you point to a very important truth about our existence: We are multi-dimensional beings–biological, psychological, social, spiritual, etc.; and while I believe that there are these fundamental existential and relational dilemmas that we all must successfully grapple with in order to experience relative wellbeing, I am in full agreement with you that when someone does becomes overwhelmed with regard to these, we have to be very careful about jumping to conclusions about which factors were most impactful in leading to this overwhelm. I’m certainly not taking a stance of saying that parents must be held responsible when a child experiences such an overwhelm (as I discussed more on the comments beneath Part One of this article, and will discuss more in Part Three). Certainly, there are so many factors that can lead to such a kind of existential breakdown—sometimes these can be fairly clearly linked to familial problems, such as overt abuse, neglect, etc., and at other times, factors external to the family dynamics are perhaps more impactful, including at times clear physiologically-rooted disabilities, social oppression, psychoactive drug use, etc. However, regardless of the factors that lead a person to become vulnerable to existential/relational overwhelm, parents are often in the best position to support that person, both by supporting that person in the individuation process to the best extent possible, and also by connecting with one’s own natural fears, insecurities, etc., and doing one’s best to reduce any harmful impact of these on the child. Based on my understanding of this situation with your son, my sense is that he is very fortunate to have such a loving and well informed family, and that you all made the best (and continue to make the best) of a difficult situation. I’m very happy to hear that you found my own limited support helpful.

A second point of clarification I feel I should make:

I said: ““Autism” is a very controversial term, not unlike “schizophrenia” in many ways, though it’s not an area that I have much experience with…”

…and you said: “I would be very careful about comparing the label of autism to the label of schizophrenia, although I think both may be invalid. Schizophrenia may represent a large group of experiences related to adjustment and finding one’s place in the world as you suggest. However, from all of my heartfelt reading and research on “autism,” I have come to believe that it may be explained on one end with individual differences and eccentricities and on the rest of the continuum as neurological damage, often dating back to prenatal exposure to toxins.”

I am generally in agreement with you here, and actually this is essentially what I was pointing to with regard to the similarities of “autism” and “schizophrenia”: That many different kinds of experiences, behaviours, etc., with likely differing etiologies get lumped under the term, “Schizophrenia,” and likewise for the term, “autism” (though again, I want to emphasize that autism is not my area of specialty). And based on my general “common sense” feeling about the situation, given how prevalent neurotoxins have become within modern society (especially prenatal maternal drug use, as suggested by the article you mentioned), I tend to agree with you that that many people who do act in particularly eccentric manners and/or exhibit certain disabilities in such a way as to be assigned to one of these two “camps” may actually have experienced some kind of neurological/physiological injury that contributed to this in some way; and also (as you mentioned) I think it is very likely that many individuals so labelled are merely naturally “eccentric,” sensitive, overwhelmed, etc., without the need to imply that there must be any underpinning physiological disease.

Warm regards,

Paris

Report comment

Thank you again Paris. I highly value and respect (and agree with) your perspective and your work.

Report comment

Thanks for this piece – it strongly resonated with me on a personal level. My own first psychosis came later than is customary , just past 30. I would say that my greatest relationship challenges at the time involved friends and peers from whose lives mine had diverged, more than any romantic crisis. But the seeds had been planted well beforehand , in ways that your research corroborates.

Many mental health professionals will generally respond to points such as yours with the argument that trauma suffered during development only increases the likelihood that illness will be triggered, and amplifies symptoms. In other words, some in the population of those who are defective were lucky enough to have advantages in life that enabled them to prevent their defects from manifesting.

One might think that believing in psychiatry, or In a diagnosis (rightly or wrongly) could help an individual with a history of trauma / alienation to ward away beliefs (theirs and others’) that they lack strength or resiliency in the face of adversity. But instead, whether the individual feels helped by psychiatry or medication or not, seeking help from either serves as a badge of shame, in just about any environment. There is nothing redeeming to anyone about becoming a psychiatric patient.

As many have said here, and as other cultural practices and open dialogue have shown, and as your piece underscores, there is much that psychiatry can learn about how to listen to the substance of a person’s thoughts and beliefs, especially while in the throes of psychosis.

Report comment

Hi N.I.,

Thanks for sharing a little about your own story. I appreciate the insights that it sounds like you’ve gained as the result of a challenging personal journey. As you allude to, if we (the collective “we” including esp. MH professionals) can drop the “illness” model of human distress and transition to the “adaptation to challenging experiences” model, I truly believe that so many of the problems you allude to here would be fairly easily resolved. Yes, we are each born into this world with certain vulnerabilities and resilience that may vary dramatically to those of others; and yes, surely many of these are related to factors predating our birth (pre/perinatal experiences/nutrition, etc. of our mother while we’re in the womb, transgenerational trauma passed down to our parents psychosocially and epigenetically, our particular pocket of human society, with its various degrees of power differentials, resourcefulness, etc.). Yet by focusing on the idea of “illness,” we foster a kind of learned helplessness, the justified forceful use of psychiatric drugs, and general self fulfilling prophecy that most readers here are only all too familiar with. If on the other hand we can focus on the power and wisdom of human adaptation, I think it changes everything–we can learn how to work directly with this wisdom as deep and as old as the universe, rather than fighting against it, to offer real support to people in distress. Anyway, one step at a time…

Best regards,

Paris Williams

Report comment

Paris, I appreciate your exploration of mutual perspectives, and also regarding the complex and transformational passage into adulthood. Even though it was almost 40 years ago for me, I can still remember vividly sorting through that exact struggle of desperately desiring my independence and at the same time wondering if I could hack it. I was terrified of life, which is what initially sent me into counseling.

Your series reminded me of one of my favorite passages by Kahlil Gibran, from The Prophet. It’s a hard teaching, but I think a good one for parents to ponder, and also for children (whether youth or adult children), to consider, about themselves.

“Your children are not your children.

They are the sons and daughters of Life’s longing for itself.

They come through you but not from you,

And though they are with you yet they belong not to you.

You may give them your love but not your thoughts,

For they have their own thoughts.

You may house their bodies but not their souls,

For their souls dwell in the house of tomorrow,

which you cannot visit, not even in your dreams.

You may strive to be like them,

but seek not to make them like you.

For life goes not backward nor tarries with yesterday.

You are the bows from which your children

as living arrows are sent forth.

The archer sees the mark upon the path of the infinite,

and He bends you with His might

that His arrows may go swift and far.

Let your bending in the archer’s hand be for gladness;

For even as He loves the arrow that flies,

so He loves also the bow that is stable.”

To me, it speaks of our inherent freedom, so it makes me think about how we develop the illusion that we are NOT free. Where does that come from? And how can we heal that illusion, so that we actually can embrace our freedom without all that insecurity and fear about it bogging us down to the point where simply cannot enjoy and be more relaxed about life? I’m thinking that to be happy and at peace with ourselves, we need to feel in control of our own lives. And that would include children.

Report comment

Hi Alex,

I remember this passage! Beautiful… Thanks for sharing it.

Thanks again for your excellent insights–I appreciate your bringing up the importance of self responsibility and personal empowerment–yes, how to find the courage and confidence to put our hands firmly upon the “steering wheel” of our lives and drive!

Paris Williams

Report comment

“…how to find the courage and confidence to put our hands firmly upon the “steering wheel” of our lives and drive!”

Bullseye! 🙂

Report comment

Hi Paris,

I think a natural extension of your concepts would involve talking about how family members who see their young son, daughter, or relative “go mad” are put into a bind themselves.

That is, at that point if they pull back and simply respect the autonomy of the young person who is psychotic, they may allow disaster to happen. But if they jump in and try to save their relative, they easily fall into doing intrusive things that can be damaging and interfere with finding autonomy. It’s very hard at that time to find a middle ground.

And the mental health system itself often falls into these same binds, and fails to find a middle ground.

If the young person can be defined as “mentally ill” and not capable of handling life in a truly autonomous way, then this solves the bind – except that the person’s identity is left damaged. But then it is declared that this is simply “truth” so any damaging by labeling and by imposed definition is denied.

A better approach is to appreciate the bind and the way it really is unsolvable, then we can talk about a variety of possible approaches (none of which are complete “solutions”) and at least figure out something to do today. That of course is what’s done in Open Dialogue…..

Report comment

Hi Ron,

Great point about the double bind the parents are placed in when their child is acting in ways that are harmful, out of control and/or has received a frightening diagnosis. I’ll go into my thoughts on this much more in Part Three (including discussing some of the key principles in the Open Dialogue approach).

In general, as you mention, I agree that the key is to recognize that a “double bind” occurs at a particular level within a system, and that by trying to “solve” the problem when (a) we have tunnel vision that only allows us to see this particular level of that system, and (b) we are in the mindset of linear causality, thinking we have to “solve” the “problem,” then I think we are likely to remain stuck, stalemated by the double bind. But if we are able to take a step back, maintain a broader more open-minded perspective (practice “easygoing in the not knowing”), practice some patience, and a willingness to be open to a deeper wisdom that lies within ourselves and others and perpetually strives towards health and wholeness, then there is every possibility that the double bind can be “transcended” (in contrast to “solved”).

I think this is akin to the famous Zen koans, in which a student is given a “problem” that is simply irresolvable via linear cause/effect thinking from within the particular system; but by being willing to allow the koan to settle into one’s being, to sit with it openly and patiently, the student is likely to experience a “jumping out of the system,” and experience a resolution that simply cannot be reached by the linear-thinking rational mind. Bateson gives an example of such a incident with a zen student: his teacher stands over him with the stick and says, “If you say this stick is real, I will strike you with it. If you say this stick is not real, I will strike you with it. If you don’t say anything, I will strike you with it.” One resolution (not solution) is for the student to simply reach up and take the stick away from the master.

As you mention, I think this is where certain kinds of family systems therapies and complex systems theories in general can be so helpful. By creating the space for open dialogue, and letting go of overly simplified linear cause/effect reasoning and preconceived ideas, we open the possibility for something genuinely new to emerge, something that may transcend the limited system of the double bind altogether and make way for something unexpected but workable.

Thanks for your engagement,

Paris

Report comment

Maybe it’s just our unique experience, and maybe it doesn’t apply to other parents, but my husband and I had to cope with a young man who should have challenged us in childhood (normal?) and didn’t, due to his nature. So, we find ourselves intruding on his life as an adult, doing things that are damaging, and that interfere with his autonomy, as you correctly put it. With a different child, this could have been cleared up in childhood, when parents are expected to intrude on their child’s autonomy to prevent them from disaster happening. That child would have rebelled against too heavy a hand. Bravo to that child. Yes, it is indeed a bind. I wanted my son out the door at 18. He didn’t want to leave. I didn’t ask to be the interfering parent of an adult child.

Report comment

“To devote so many years and resources towards the life of this being, and then to simply let them go free into an unpredictable and frankly dangerous world . . . this is no easy task for any loving parent, and yet if we want our children to experience the fullness of mature adulthood, this is exactly what is called for.”

Being a good parent is quite the opposite of today’s me generation, ‘it’s all about just me,’ belief system. One’s job is pour one’s heart and soul into loving, training, and educating one’s children. Then selflessly render oneself “irrelevant to reality” to one’s beloved children, at the point they are ready for such a thing, not necessarily when mom is ready. But also not when psychiatrists have delusions this should occur, in my family’s case, when my children were the age of 3 and 6.

I was thankfully able to continue to function fairly well in my job as a loving mother and active volunteer, by keeping copious calendar notes, despite the psychiatric anticholinergic intoxication poisonings, to which I was subjected. It’s good such “psychosis” causing poisonings result in one being “hyperactive,” rather than “inactive” – resulting in my being one of the very active ‘super moms’ in my neighborhood. Also resulting in my having to let my children “go free into an unpredictable and frankly dangerous world” early, since our local school district was not “equipped to deal with the children who get 100% on their state standardized tests,” by the time my children reached the 8th grade. Although, I’m quite certain many people would not have been able survive the massive poisonings to which I was subjected, so such for profit psychiatric attacks on stay at home mothers, should end.

Being a parent is a counterintuitive job, given the fact it is a job, that should not end up being a life long profession. But so far, so good, my children are both fairly self sufficient and responsible, at their still young ages of 17 and 20. One graduated as valedictorian of his high school class, and is doing well in college. The other graduates this year, and is trying to figure out where she wants to further her education.

And I will say, my friends and I who did stay at home, volunteer in the schools, and actually work hard to be good parents, did definitely end up having the children who were the most emotionally stable and self confident, and our children were all in the top of their classes. So I disagree with our current society’s disrespect for stay at home parents, and the job they do. Parents are much better at raising their children, than the state, IMHO. I find it shameful today’s psychiatric industry is attacking stay at home moms with young children, claiming we are “irrelevant to reality,” “unemployed,” and “w/o work, content, and talent.” Ironically, my psych “professionals” children are drugged and doing poorly now.

Perhaps we should swing back to a society which is wise enough to understand that properly raising children is an important job, because properly raised children become good citizens. Improperly raised children, or drugged children, often become criminals and drug addicts, in other words, not particularly good citizens. It’s a shame the psychiatrists don’t understand this. But it seems currently, it is their job to drug up absolutely everyone who is not functioning as a debt slave and paying unconstitutional income taxes to the bankers who have taken over the US monetary system, and who have now made a complete mockery of our monetary system.

Report comment

Hi Someone Else,

Thanks for sharing your wisdom and life experience with us.

I think these are very important points you bring up. It’s true that contemporary society has become increasingly individualistic in so many ways, and I think there’s no doubt that his has wreaked havoc on the ability to raise our children in genuinely healthy and nurturing ways. It’s an inspiration to hear from someone such as yourself who has managed to resist the individualistic push from our society, and to remain so committed to your children.

Best regards,

Paris

Report comment

Paris – I really think you’re on to something with your unified theory – write on!

In terms of sub-optimal attachment, the impact on neurodevelopment is profound. (Dan Siegel comes to mind) especially the ability to tolerate distress and self-soothe can be compromised.

Looking forward to Part 3.

Report comment

Hi Wayne,

Thanks for your words of support. I’m a fan of Dan Siegel as well, who I see as someone pushing for a holistic organismic view of the human being, but simply entering through the neuroscience door.

Best regards,

Paris

Report comment

An intriguing and in my view extremely accurate and meaningful article. I have to say, though, I was surprised that you didn’t take the next step when talking about parents’ reaction to their children’s separation. It seems clear to me that parents who have their own issues with attachment have a much harder time with this, as they perceive abandonment and/or rejection by their own child/children, as well as having their identity as a parent, which for some is their primary identity, become increasingly obsolete. I experienced this to a degree with my own mom, though she appeared to show some uncharacteristic awareness of this and took some steps to make it a little easier on me. My wife experienced this phenomenon to a much more intense degree with hers. Her mom was literally in tears when she moved out, saying things like “You held the family together!” and “What will we ever do without you here?” It was quite appalling to me to hear about, partly because I was toward the end of my own course of quality therapy at the time and could see the awful bind she was putting her daughter in.

I like to think we’ve been able to avoid passing most of this on to our kids, but it is a very hard time for parents like us who haven’t had the greatest attachment experiences, and making it clear to parents that their pain is not caused by their kids leaving but by their own unresolved history seems like a very important point to keep in mind.

Thanks for sharing your insights and excellent writing skills!

—- Steve

Report comment

Excellent points, Steve. And thanks for sharing a bit about your own trials and tribulations as a child and as a parent. I’ll talk a bit more in Part Three about the implications of a parent’s own attachment wounds. As you may be aware, Dan Siegel has written a lot about these very issues, and how the research shows that one of the most helpful things that a parent can do to support their own child’s healthy relational development (i.e., develop secure attachment styles) is to work on resolving their own attachment wounds, esp. via developing a “coherent narrative” of one’s life and mindfulness practice.

Best wishes,

Paris Williams

Report comment

OK…no arguments regarding the emotional dialectics you mention…my focus is the broader context, which is at least as important as the particulars, which do contain echoes of Laing’s “Sanity, Madness & the Family” which I read long ago. It’s not clear whether these insights are considered to be primarily culture-bound or as transcending western culture.

… healthy development requires that we undergo a transition in our primary attachment figures, from our parent(s)…to a romantic partner, with a relatively secure and longstanding romantic relationship generally considered the most natural and optimal developmental aim in this regard.

But here we go with the “healthy”…so what is “generally considered” to be “healthy,” in other words, seems to be monogamy, am I right? (I think the term “romantic” needs to be looked at as well.) What of the consequences of living outside of what this undefined consensus deems “healthy”?

(Very thought-provoking btw, my responses are not intended to seem hostile.)

Report comment

Hi oldhead,

Your comments are not taken as hostile at all — to the contrary, I really appreciate your directness.

Great comment about our need to be cautious with our terminology and the assumptions implied therein. I actually fiddled with this particular sentence a few times before leaving it as you found it here in this article, not entirely comfortable with how I wrote it, but also not coming up with a way of saying it of which I felt more comfortable. So I’ll clarify my thoughts a bit more about this here. I said:

“The second particularly critical period with regard to healthy individuation occurs in late adolescence and early adulthood. It is at this stage that healthy development requires that we undergo a transition in our primary attachment figures, from our parent(s), who have likely been our primary attachment figures up until this point, to a romantic partner, with a relatively secure and longstanding romantic relationship generally considered the most natural and optimal developmental aim in this regard.”

By “romantic relationship,” I’m referring simply to the way that, as we mature into adulthood, most of us are “wired” to develop a deep attachment to a peer (as opposed to parent or family member) of both an emotional and a sexual nature. Notice that when I said, “a relatively secure and longstanding monogamous romantic relationship generally considered the most natural and optimal developmental aim in this regard,” I qualified this with the phrase, “generally considered”, meaning that within most human societies, this is considered the most “healthy” developmental aim; though certainly there are some cultures and subcultures with very different values and structures around this, and I don’t think it’s my place to directly challenge that.

As for my use of the term, “healthy development,” I’m defining “health” as simply the capacity to experience maximal wellbeing given the particular challenges of our current situation in life. Of course, wellbeing is a subjective experience–we have to honor each individual’s experience of this in their own life. But generally speaking, I think it’s safe to say that the majority of people experience maximal wellbeing when they are “securely attached” (in the context of the article here) to other human beings, with these typically being our primary caretakers when we’re children, and typically more peer-oriented romantic partners and/or close friends and family when we’re adults.

I appreciate your healthy skepticism around the use of certain terminology and the often hidden assumptions associated with them. I really value that. I kind of see this as the double-edged sword of language–on on hand, we need language and words to effectively communicate with each other; on the other hand, language/terminology can be very powerful in that it comes loaded with certain assumptions that are often well hidden. So I think it’s essential that we regularly “lift up the carpets” beneath the words we use, sweeping out these hidden assumption into the light of day.

Paris Williams

Report comment

I guess the only term I sort of tripped over was “romantic,” which is open to interpretation. The expectation that marriage should include “romance” in the storybook sense is relatively recent; economic factors were predominant throughout much of history.

So anyway:

I think it’s safe to say that the majority of people experience maximal wellbeing when they are “securely attached” (in the context of the article here) to other human beings, with these typically being our primary caretakers when we’re children, and typically more peer-oriented romantic partners and/or close friends and family when we’re adults.

That opens it up more. Ideally the autonomy/attachment dialectic could resolve in different ways, without social sanctions, with different proportions of autonomy and attachment as needed by different individuals to achieve their optimal psychic balance. Also the types and number of relationships which fulfill our attachment needs can vary widely.

Report comment

Hi Paris, thanks for these articles.

Part 1 was one of the best things I’ve ever read on the subject of what’s really causing mental health issues, and I’m sharing it around as much as I can. Thank you!

I just wanted to mention that I think God is the elephant in the room with the whole discussion of mental health. We’re rightly focusing on the fact that modern society has become such a breeding ground for bad character traits, fear, worry, anger, control issues, and all the other negative things that create the heady brew required for mental and emotional illness to thrive.

But a huge part of why society is becoming so rotten and ‘anti-social’ is because the focus has been placed on superficiality and materiality, instead of spiritual achievement, true purpose and striving.

I know God has been co-opted by many man-made religions with their own (materialistic) ends in mind, but that doesn’t mean that He doesn’t exist, or that the soul is not a fundamental part of the quest for human health and happiness at every level.

Ignoring God and the spiritual imperative that underlines the whole reason why we’re here in the first place, and why we have to suffer, and how we are meant to learn and grow from these experiences, means that any solution we arrive at is limited and partial, even with the best of intentions.

Anyway, wonderful articles, thanks again for putting them together, and pulling so much useful research into one place.

Rivka Levy

Jewish Emotional Health Institute

Report comment

Hi Rivka,