When I first entered a state of altered reality (called psychosis) at the age of 25, I was exhilarated. Then, when I could not return to consensual reality, I was terrified. I have been trying to understand ever since why my mind went to such an extreme state and why I could not return without heavy assistance (medication and hospitalization). I now feel I truly understand my altered state at a much deeper level. I hope this understanding will help others, as it is helping me. I think the more we explore these altered states, the more we will be able to guide people through them without medication or hospitalization.

My Insight (which I guess schizophrenics are capable of after all Dr. Torrey):

Recently, after a trip to Michigan, I awoke wondering where I was. This sometimes happens to me and to other frequent flyers after a trip. It causes me some anxiety. Usually I jump out of bed and start to explore my surroundings. This time, though, instead of jumping up in a slight panic, I decided to keep my eyes closed and started to ask myself a series of questions.

“Where was I yesterday?” I asked myself.

“I was in northern Michigan,” I answered.

“Am I still in Michigan?” I wondered.

“No, I seem to be in different place,” I answered.

“Had I flown last night?” I inquired of myself.

“Yes, I had been on a very late flight from Michigan to Boston,” I responded.

“That’s it, I am home in my own bed in Cambridge.” With that realization, I opened my eyes and it was true.

An Open Dialogue Interpretation of my Experience:

At that moment I felt I understood why the Open Dialogue description of psychosis makes sense. The Finnish developers of Open Dialogue (Seikkula, et al,2006) describe psychosis as monologue. They say that the healthy state of living is to be engaged in an ongoing dialogue with significant people in your social network. Through stress and trauma, sometimes a person in the social network may feel overwhelmed and as a result retreat into monologue (or we might describe it retreat into one’s own world).

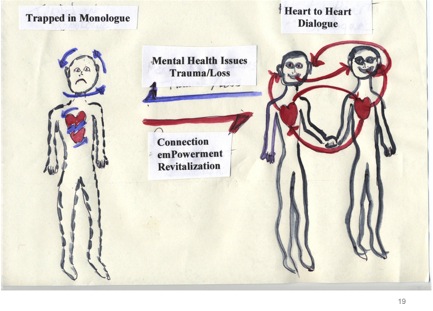

In this condition of monologue, one is no longer able to connect, especially on an emotional level with the persons in one’s social network. There is only one voice driving your actions. That voice seems to come from outside ones own self and controls one’s life. This description of psychosis so closely conforms to my own experience that I drew a picture of this process of going into psychosis and recovery from it as shown below:

If we look at the two people on the right, we see they are closely connected at both their verbal or cognitive level and nonverbal or heart level. In Open Dialogue terms, we would say they are engaged in dialogue. I call this heart-to-heart dialogue. Though this is drawn as just two people, who may be in love, in reality it is a social network of people similarly engaged. In dialogue, there are many voices contributing to the ongoing process of understanding the world around the network.

Perhaps at some point, the people in the network are subjected to trauma and loss. This stressor can cause one or more of its members to withdraw into their own world, which in Open Dialogue terms is called a state of monologue. The condition of the person in monologue is depicted in the drawing of the person on the left. The arrows circling about their head indicate thoughts that go around and around inside in a repetitive fashion. There is little communication between the person and their heart. In the words of one young man prone to periods of psychosis, the person’s heart stopped talking to them.

The young person told me that his heart stopped talking to him when he was isolated. He also reported that was when his heart stopped talking to him, he heard voices. He added that when he was with his friends, his heart talked to him again, and he stopped hearing voices. In other words if someone stays in a state of monologue too long and the monologue is too severe, psychosis can occur and one can hear voices.

EmotionalCPR: a form of emotional dialogue:

During the last 4 years, I and 20 other persons with lived experience of recovery have been developing a method for assisting persons in acute crisis to transition back from a state of monologue to dialogue. We call this approach emotionalCPR or eCPR. This activity involves a person Connecting with another person in a manner which facilitates their experience of emPowerment, and Revitalization. The person assists the person in monologue to return to dialogue through heart-to-heart resuscitation on an emotional heart level. This is analogous to CardioPulmonaryResusitation or CPR for the physical heart. In the figure above, the elements of eCPR are shown as vital to restoring a person’s engagement in dialogue.

Lets return to my morning of disorientation. At an earlier stage in my life, after traveling, I would wake up and experience a temporary disorientation. I would wonder where I was. I would know the place was not the place I was in yesterday. I would become anxious and not be able to think or remember how I got to this different place. I would have to get up and start exploring my surroundings because I would feel very alone in my quest. I would not ask questions of myself because there is no one to answer them. It is only I without a sense of myself. I was on a quest without questions.

This state of mind is technically called a hypnagogic state, which is a state of consciousness between being asleep and awake. I recall being in that state of mind for a prolonged period when I was in psychosis. It was like a waking dream. It was as if my dream world was spilling into my waking world. At first it was thrilling. I felt at one with the world about me. Temporary periods of such waking dreams can be very revealing and may be the states of mind of greatest creativity. They may be the periods of artistic creation and of creation of an integrated self. However, if they are accompanied by panic by oneself and the people around one then those states of mind can result in psychosis.

By this description then psychosis is a monologue state of mind during which it is difficult to return to everyday reality without the assistance of a trusted guide. In that monologue state of mind, there is an I but little capacity to experience a me inside to reflect or answer questions. The best guides for escorting people back from states of being trapped in monologue are peers who have experienced those states of mind and recovered a grip on the life of everyday reality.

Lessons Learned:

What I discovered during my morning of disorientation was another way to avoid psychosis. I discovered that I now have the capacity for inner dialogue, which I did not have when I was in my 20’s. Recently, when I was asking myself questions and then answering them I was experiencing my inner dialogue. Instead of my quest for understanding reality by only exploring my external world, I could carry out my quest through questions within my internal world. In psychology this is called the development of an observing ego or sense of self, which is greater than ones immediate experience.

Emotions play, I believe a vital role in the growth and the exercise of this self. In addition to the inner verbal dialogue, I also went through an inner emotional dialogue. In fact, the whole new line of dialogue was activated by my fear. Instead of running from my fear, causing it to grow to panic, however, I allowed myself to experience it. I then considered the fear an important signal that I needed to examine the situation more carefully. I think strong emotions help call our attention to undisclosed parts of our self. Then by experiencing the emotion, it is possible to understand where it came from and think differently about its cause. This sequence allows for the building up of a sense of self which at a future time will make it easier to engage in the self soothing dialogue essential to avoiding of repeated psychosis.

Ways Our Present Psychiatric System Interferes with Our Recovery and Development

Unfortunately, this whole learning experience is interfered with by our present psychiatric system. The mental health system presently regards the expression of almost any strong emotion as a symptom of some type of mental illness. Extreme fear, is labeled paranoia. Heavy sadness becomes depression. Temporary confusion becomes psychosis. Anger is mania. This pathological redefinition of emotions as symptoms is just an exaggerated form of our industrial, northern culture, which demands that everyone keep a stiff upper lip. It is a culture of dead men walking. When a person experiences emotions, which are uncomfortable for their social network, they are medicated. There is growing evidence, however, that early and prolonged medication actually interferes with recovery (Whitaker, 2010).

Parallels between Early Treatment of Polio and Present Day Treatment of Psychosis

Our treatment of psychosis is similar to the story of the treatments for polio, prior to polio vaccines in1952. The usual practice with polio victims was to immobilize the person’s limbs or whole body for months. This was followed by use of heavy braces, because the patient could not use their limbs without the braces. Then a nurse from the bush of Australia, Sister Elizabeth Kenny, developed an alternative approach. She found that the polio was not itself causing paralysis. Instead, she found that the treatment of immobilization and braces was causing paralysis because the immobilization and braces were causing muscle atrophy. She found that the poliovirus caused temporary muscle spasms, which could be treated with, warm compresses and stretching exercises.

When the patient was attended in this fashion, along with the hope and expectation of the persons treating that they would recover, they indeed did recover. Just like our recovery movement, the traditional medical establishment rejected Sister Kenny. But she came to the US in 1940 and three brave doctors at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota tried her technique. They proved that it worked and for 10 years they applied it at their clinic with excellent results. Once the polio vaccine was developed in the 1950’s her technique was no longer needed. However, the procedures she developed made a positive contribution to rehabilitation of a variety of neuromuscular conditions today.

The analogy between Sister Kenny’s approach to polio and the Finnish approach to psychosis is very compelling. Instead of viewing psychosis as a permanent condition, needing lifelong medications, a type of immobilization and brace to the mind, Open Dialogue views psychosis as a temporary condition. In this analogy, psychosis is a type of social spasm between the person and their social network. In Open Dialogue, the treatment is a massaging and stretching of the social network of the person in distress rather than their immobilization by medication and hospitalization. This enables the person affected to once again use their mind without the iatrogenic effects of lifelong diagnosis, medication, and hopelessness.

It appears that the facilitation of outer dialogue through Open Dialogue or eCPR can bring a person in distress out of the position of being trapped in monologue. But there is still the need on the person’s part to develop that inner voice and inner dialogue, which enables them to remain, connected dialogically with the people around them. I believe that we develop this inner dialogue by fashioning our self through our emotional connections with significant persons in our life. This, I believe is crucial to developing the resilience needed to avoid future relapses into psychosis. The expression and acceptance of strong emotions seems to be a critical component to this growth of self.

Voice and Dialogue Training May Help Build Resilience to Protect against Being Trapped in Monologue:

I believe this learning can be stimulated through role-plays, which are actually real plays. Such a real play occurred in a recent training or mutual learning I carried out in Michigan. The mutual learning experience is called Voice and Dialogue Training. It involves coaching peers to become facilitators of a process I call Recovery Dialogues. The purpose of the Recovery Dialogues is to help clinicians shift from a traditional monological, medical model culture to a dialogical, recovery-oriented culture.

This shift should ease the tension experienced by peers working in traditional clinical settings. A real-play of a Recovery Dialogue was set up in which two peers played the role of the typical clinicians, one played a drug rep and three peers played the role of peer specialists. The group picked the topic of hope. There were two dialogue-trained facilitators. During the first 20 minutes each person’s perspective on hope was stated. Those in the clinician role emphasizing that these are life-long conditions, for which life-long medication and clinical supervision of the person’s life were necessary. Maintenance was the best to hope for.

The peer specialists emphasized the importance of hope and self-determination in recovery. Then there was a more concentrated conversation between the person playing the role of a drug rep and peer. The peer said she had come off her medication and was doing well. The drug rep kept repeating that these illnesses are cyclical and that they will need to go on the medication again and again.

At that point the peer started to cry, though she continued to make her point that she wanted to continue off the medication and that she believed in herself. Though tearful, she remained resolute and the drug rep and the other traditionally oriented players visibly were moved. They started to listen in a new way. In the processing of the real play, those playing the traditional roles said they could feel a difference when the peer cried. It swayed their perspective.

To date these types of real plays seem safer among peers than between peers and clinicians. I have carried out such recovery dialogues at a community mental health center over the last 3 years. Such moments of emotional expression and shifting attitudes happen, though they are harder to achieve. The more we can learn about the process among peers, the easier it will be with others. In the future, I am hopeful they can be carried out for the general population in what we are calling Community Recovery Dialogues.

References:

Seikkula, J., Aaltonen, J., Alakare, B., Haarakangas, K., Keranen,P., and Lehtinen, K. Five-year experience of first-episode psychosis in open-dialogue approach. Psychotherapy Research. 16:214-228 (2006).

Whitaker, R. Anatomy of an Epidemic. Crown Publisher, NY. (2010).

This is good. Worthwhile. Thank you for a nice piece.

Report comment

I learned a lot from reading this. Thank you

Report comment

A truly wonderful essay Dan, and another fine example of a hopeful shift towards critique and curiosity about the true nature of psychosis? Was Plato right about madness as a divine gift, as we learn to be curious rather than fearful and critical?

Your description of disorientation reminds me of my own experience of bipolar type 1’s mania, as a waking dream of elation fueled euphoric ecstasy? A strange place beneath my usual social dialogue, where a sharper waking sense of separation, glimmers, shimmers and threatens to dissolve? At its deepest level it feels like I’ve fallen within, perhaps subtle memories of “state,” awareness pre-birth?

On a functional level there is a new appreciation for the field of “out there” objective reality, with a re-born desire for approach and engagement, where previously wary avoidance had been my behavioral routine. Avoidance on a purely physiological level, rationalized in self-dialogue as fierce independence, although counter-dependence is a more accurate interpretation, beyond my need to soften a harsh existential reality? Being honest with myself, about myself can sometimes feel a bit brutal, and I appreciate with renewed compassion, ancient rights of passage, we modern educated super-men often consider, savage?

I guess my point here, is the subtle trap contained in our cognitive capacity and social dialogues, as an escape from the primary process reality of the body, and the very ground of our being? I think its a most pertinent question in our exploration of “psychosis,” which I suspect can only be further elaborated by those of us who know its actual experience, on a felt level?

Yet of coarse, when comes to translation into communicative dialogue, we’re still very much suck in the zeitgeist of clockwork logic, particularly in this black & white, written format? How do we go beyond cause and effect to embrace a paradigm shift into systemic awareness? That all at once fluid reality, in our experience of NOW?

Why does psychosis feel like a waking dream or nightmare?

“The Dream? A Container of Existential Reality?

Why do both the negative and positive experiences of psychosis feel like a waking dream or nightmare? Why is the dreaming state, considered the very crucible of Madness? Consider Jaak Panksepp’s brilliant, “Affective Neuroscience – The Foundations of Human and Animal Emotions,” and a chapter entitled;

“Sleep, Arousal, and Mythmaking in the Brain:

Shakespeare proposed one possible function of sleep when he suggested that it “knits up the raveled sleeve of care.” Each day our lives cycle through the master routines of sleeping, dreaming, and waking.

Although we do not know for sure what the various sleep stages do for us, aside from alleviating tiredness, we do know about the brain mechanisms that generate these states.

All of the executive structures are quite deep in the brain, some in the lower brain stem. To the best of our knowledge, however, the most influential mechanisms for slow wave sleep (SWS) are higher in the brain than the active waking mechanisms, while the executive mechanisms for REM sleep are the lowest of the three.

Thus, we are forced to contemplate the strange possibility that the basic dream generators are more ancient in brain evolution that are the generators of our waking consciousness.

The brain goes through various “state shifts” during both waking and sleep. Surprisingly, it has been more difficult for scientists to agree on the types of discrete states of waking consciousness than on those that occur during sleep. EEG clearly discriminates three global vigilance states of the nervous system–waking, SWS, and dreaming or REM sleep.

Some people have also thought that dreaming is the crucible of madness. Many have suggested that schizophrenia reflects the release of dreaming processes into the waking state. Schizophrenics do not exhibit any more REM than normal folks, except during the evening before a “schizophrenic break,” when REM is in fact elevated. There seem to be two distinct worlds within our minds, like matter and antimatter, worlds that are often 180 degrees out of phase with each other.

The electrical activity in the brain stem during dreaming is the mirror image of waking–the ability of certain brain areas to modulate the activity of others during waking changes from excitation to inhibition during REM. In other words, areas of the brain that facilitate behaviors in waking now inhibit those same behaviors. Many believe that if we understand this topsy-turvy reversal of the ruling potentials in the brain, we will better understand the nature of everyday mental realities, as well as the nature of minds that are overcome by madness.

Perhaps what is now the REM state was the original form of waking consciousness in early brain evolution, when “emotionality” was more important than reason in the competition for resources.”

Certainly in my own experience the dream like state of a euphoric mania, enabled me to overcome a highly defensive muscular posture, and approach others openly instead of in a self-defeating all to wary of threat, attempts at social engagement. Defeated by the unconscious signals to others about my fearful inner state, and kept in this unconscious pattern by signals to my own brain-nervous system, from my habitual muscular bracing. My birth trauma conditioned postural attitude to life?

The dream state feeling of euphoric mania, acted as a container for an existential reality of innate fear-terror, which threatens to annihilate the conscious mind in any normal waking approach. Any normal conscious awareness which has not been conditioned by experience, to deal with this brutal aspect of our existential reality. In our modern world of assured survival, the ancient rituals of a young man’s right of passage have been been largely forgotten. Yet teaching the young man to face the reality of a life eats life survival, and its real-life possibility of shear terror, were once a vital experience for survival. What ancient trace memories are sometimes contained within our nightly dreams and nightmares?”

http://www.born2psychosis.blogspot.com/p/chp-12.html

Are we beginning to move away from all to quick negative judgement about psychosis experience, as people begin to resist the traditional cover-up, stimulated by fear of shame, and we learn to openly and honestly share our lived experience? Are we indeed falling into a new zeitgeist? (spirit of this age)

As JZ Knight implores of us, “are we indeed, fearless entities after a dream?” Or from Paris Williams brilliant dissertation;

“One might say that the Self wants to know itself, or that God is trying to discover himself, the Anthropos we are living in is trying to wake up, the collective unconscious is trying to express itself or the universe is evolving in such a way as to make us more aware of the meaning of life.” _ Mindell (2008)

Be well,

Dan.

Report comment

Thank you for your thoughtful reply. I will look up your references. The interplay of the different levels of the nervous system and their role in the sleep-wake cycle is very relevant to these altered states of reality. It seems that we need to be more aware of our emotional/social dimension of life. If we are not, individually and collectively, as is happening in today’s world, it bursts through as states of altered reality, waking us up to that deeper reality. Perhaps we are asleep when we are awake and truly awake to our true selves when we are dreaming. Certainly the Buddhists would say that.

Report comment

Hi Dan,

Thanks for your response, certainly a daily Buddhist practice has allowed me to sink deeper into the ground of my being (my body), with surprising shifts in my metaphors of self-interpretation. Although the shifts come from a joining of East & Western knowledge, as the objective discoveries of Western science are blended with the subtle awareness taught by the Prince of sense-ability.

A teacher so gifted that his real message is left behind in images of posture rather than words, spending hundreds of hours simply contemplating his postural messages has helped a shift of inner awareness, which could not be grasped by my cognitive capacity. His most potent image, is of a supremely calm face with a complete lack of muscular tension, indicating he was aware of what modern science is now discovering in the evolution of our human head and facial muscles, or what Stephen Porges calls the face-heart connection.

I was caught in two minds yesterday with your wonderful essay, and the graphic examples of the reality of heart to heart healing, much of which happens beneath our conscious awareness, in hidden brain-nervous system activity. I chose to address the dream like nature of active psychosis, while equally wishing to address a face-heart connection in healing and recovery.

Particularly because, on a pure science level “The Polyvagal Theory,” addresses all the issues of the recovery argument and provides a means of “inclusive” rather than exclusive dialogue. The kind of objective science fact, which might convince those less set in their ways psychiatrists, to turn further away from the medication only approach to healing and recovery? Consider;

“The muscles of the face and head influence both the expression and receptivity of social cues and can effectively reduce or increase social distance.

Neural regulation of these muscles can reduce social distance by making eye contact, expressing prosody in voice, displaying contingent facial expressions, and modulating the middle ear muscles to improve the extraction of human voice from background sounds.

• A face–heart connection evolved as source nuclei of vagal pathways shifted ventrally from the older dorsal motor nucleus to the nucleus ambiguus. This resulted in an anatomical and neurophysiological linkage between neural regulation of the heart via the myelinated vagus and the special visceral efferent pathways that regulate the striated muscles of the face and head, forming an integrated social engagement system.

• With increased cortical development, the cortex exhibits greater control over the brainstem via direct (eg, corticobulbar) and indirect (eg, corticoreticular) neural pathways originating in motor cortex and terminating in the source nuclei of the myelinated motor nerves emerging from the brainstem (eg, specifi c neural pathways embedded within cranial nerves V, VII, IX, X, and XI), controlling visceromotor structures (ie, heart, bronchi) as well as somatomotor structures (muscles of the face and head).” The Role of Social Engagement in Attachment and Bonding.

“Immobilization Without Fear:

Humans have three principal defense strategies—fight, flight, and freeze. We are familiar with fight and flight behaviors, but know less about the defense strategy of immobilization, or freezing. This strategy, shared with early vertebrates, is often expressed in mammals as “death feigning.” In humans, we observe a behavioral shutdown, frequently accompanied by very weak muscle tone.

The human nervous system, similar to that of other mammals, evolved not solely to survive in safe environments but also to promote survival in dangerous and life-threatening contexts. To accomplish this adaptive fl exibility, the human nervous system retained two more primitive neural circuits to regulate defensive strategies (ie, fight–fl ight and death-feigning behaviors). It is important to note that social behavior, social communication, and visceral homeostasis are incompatible with the neurophysiological states and behaviors promoted by the two neural circuits that support defense strategies. Thus, via evolution, the human nervous system retains three neural circuits, which are in a phylogenetically organized hierarchy. In this hierarchy of adaptive responses, the newest circuit is used first; if that circuit fails to provide safety, the older circuits are recruited sequentially.

In safe environments, autonomic state is adaptively regulated to dampen sympathetic activation and to protect the oxygen-dependent central nervous system, especially the cortex, from the metabolically conservative reactions of the dorsal vagal complex. However, how does the nervous system know when the environment is safe, dangerous, or life-threatening, and which neural mechanisms evaluate this risk?

Environmental components of neuroception

Neuroception represents a neural process that enables humans and other mammals to engage in social behaviors by distinguishing safe from dangerous contexts. Neuroception is proposed as a plausible mechanism mediating both the expression and the disruption of positive social behavior, emotion regulation, and visceral homeostasis. Neuroception might be triggered by feature detectors involving areas of temporal cortex that communicate with the central nucleus of the amygdala and the periaqueductal gray, since limbic reactivity is modulated by temporal cortex responses to the intention of voices, faces, and hand movements. Thus, the neuroception of familiar individuals and individuals with appropriately prosodic voices and warm, expressive faces translates into a social interaction promoting a sense of safety.

In most individuals (ie, those without a psychiatric disorder or neuropathology), the nervous system evaluates risk and matches neurophysiological state with the actual risk of the environment. When the environment is appraised as being safe, the defensive limbic structures are inhibited, enabling social engagement and calm visceral states to emerge. In contrast, some individuals experience a mismatch and the nervous system appraises the environment as being dangerous even when it is safe. This mismatch results in physiological states that support fi ght, fl ight, or freeze behaviors, but not social engagement behaviors. According to the theory, social communication can be expressed efficiently through the social engagement system only when these defensive circuits are inhibited.

Three Neural Circuits That Regulate Behavioral Reactivity:

Infants, young children, and adults need appropriate social engagement strategies in order to form positive attachments and social bonds. At the University of Illinois at Chicago, we have been developing a model that links social engagement to attachment and the formation of social bonds through the following steps:

1. Three well-defined neural circuits support social engagement behaviors, mobilization, and immobilization.

2. Independent of conscious awareness, the nervous system evaluates risk in the environment and regulates the expression of adaptive behavior to match the neuroception of an environment that is safe, dangerous, or life threatening.

3. A neuroception of safety is necessary before social engagement behaviors can occur. These behaviors are accompanied by the benefits of the physiological states associated with social support.

4. Social behaviors associated with nursing, reproduction, and the formation of strong pair bonds requires immobilization without fear.

5. Oxytocin, a neuropeptide involved in the formation of social bonds, makes immobilization without fear possible by blocking defensive freezing behaviors.” NEUROCEPTION: A Subconscious System for Detecting Threats and Safety, STEPHEN W. PORGES.

We tend to draw battles lines in this most emotive of human issues, perhaps without really knowing why, yet as Nelson Mandela points out;

“If you talk to a man in a language he understands, that goes to his head. talk to him in his language, it goes 2 his heart”_Nelson Mandela.

Is Stephen Porges groundbreaking discovery the kind of language which can go to the heart of psychiatrists desperate for a scientific foundation to the ART of psychotherapy? And is it the kind of science language we can use to validate the peer recovery approach, and capture hearts and minds in the mainstream media?

Report comment

Hope.

Your words are always full of hope!

Duane

Report comment

And empathy, warmth, understanding, love.

Thank you!

Duane

Report comment

Dan

Another great contribution to this blog. I love how you and Paris Williams have aplied real science (as opposed to the phony reductionist approaches of Biological Psychiatry) to such deeply personal and psychological experiences of extreme states of emotional stress. Hopefully this can be another nail in the coffin that hastens the demise of the oppressive medical model.

I have a question about the use of the term “consensual reality which I will address under Paris Williams posting.

Report comment

I found this a very interesting and useful article. I have recently started working as a Peer Specialist and am hopeful that I will be able to help others, as you suggest, to regain their sense of self and of reality.

Prior to each of my psychotic breakdowns, I was extremely sleep deprived, and I find now that a good sleep pattern is a cornerstone of staying mentally well.

In fact, routine of all sorts helps – regular meals, exercise, the rigours of work, and so on.

And, as you say, growing older helps – we become calmer, more self-aware, more secure in ourselves. All these things should prove reassuring to those who suffer psychotic breakdown – and especially the knowledge that recovery is a reality.

Thank you Daniel, for being such a shining example to us all. One day I would like to follow in your footsteps and gain some medical qualifications; meanwhile I will continue to watch and learn.

All the best

Louise

Report comment

Dan,

Re: “trying to understand” a “psychosis”

A quote that I love:

“Life is not a problem to be solved but a mystery to be lived.”

It seems to me that the “answer” lies in the experience itself… as something that was supposed to be lived, in order to transform, to grow, to become more fully human.

My best,

Duane

Report comment

I’m grateful that you and Michael Cornwall are in this time and place… You both bring such gifts!

Be well,

Duane

Report comment

Please note: What follows is at least as much a critique of the currently existing (entirely laudatory) comments on this page, as is it a critique of Dr. Fisher’s post; though, it is a critique of that, as well…

11 comments on this page before mine; none are the least bit critical of this, “New Understanding of ‘Psychosis’”?

Well… At age 21.5 (more than a quarter of a century ago), I could have greatly benefited, I believe, from Dr. Jaakko Seikkula’s Open Dialogue.

But, was I “Trapped in Monologue” (as Dr. Fisher describes)?

In all sincerity, I quite admire the author’s ability to articulate his own “lived experience” of what he calls “psychosis” — and appreciate his desire to advance Open Dialogue; but, with all due respect, I do not believe anyone’s ‘lived experiences’ – in terms of what’s called “psychosis” – are universal. Do all the commenters preceding me disagree with this point???

Dr. Fisher seems to present his own experiences as definitive.

And, so, I am concerned that, possibly: instead of setting up an (‘Open Dialogue’) environment, in which a young person entering the sort of personal-interpersonal crisis such as I had, in my early twenties, could be fully heard, Dr. Fisher may be inclined to project his own experiences.

Projection is, perhaps – to an extent – inevitable when those with self-described “lived experience” are addressing a perceived ‘first episode of psychosis’; but, it should not continue once it is pointed out.

(So, who will point these would be errs of a much beloved doctor while he’s bathing in the admiration of his blogging community? Though hesitant to comment, at all, on this web site, I proceed here for the sake of those whom Dr. Fisher shall be addressing in his work.)

From this perspective, I ask, first of all:

Dr. Fisher, is this “new” view which you offer (of ‘psychosis’) at all new, in reality???

Perhaps, to you, it is new. To me, it seems very old.

“There is little communication between the person and their heart. In the words of one young man prone to periods of psychosis, the person’s heart stopped talking to them.”

As far as I can tell, you’re painting so-called “psychosis” (and, perhaps, so-called “schizophrenia”) as a ‘heart-mind split’; that’s an old view – a *very* old view – which may work for some; but, it will not work for many (such as I).

Many have presented it that view; many – such as I – reject it.

That model simply cannot account for people (such as myself and *many* others) who – while coming to be, by a general consensus of their community, viewed as ‘psychotic’ – were actually in the midst of a process, of very deeply exploring (and, thus, were, in fact, variously melding) mind and heart.

In the midst of what is called “psychosis,” many (countless people) experience a self-described “spiritual awakening” – which should not be devalued; and, amongst these folk, many have a rather exceptional ability to dialogue with themselves. (You say of yourself, “I discovered that I now have the capacity for inner dialogue, which I did not have when I was in my 20′s.” Wonderful. That you’ve developed such a capacity now. But, please understand: many do have that capacity, when, in their 20’s, they come to be viewed as experiencing ‘psychosis’.)

Most psychiatrists devalue ‘psychosis’ experiences, terribly; they love nothing so much, as an opportunity to ‘medicate’ a perceived “psychotic” person.

And, of course, typically, the family (and friends) adamantly disagree with that supposedly “psychotic” person’s self-appraisals, of what s/he is experiencing, in terms of ‘awakening’; but, would your Open Dialogue ‘treatment team’ take that same tack, necessarily? I certainly hope not.

Yet, what would have become of me had I been, at age 21.5, subject to an Open Dialogue inspired by your views, as stated, in this blog post? I am concerned, that such a team would automatically agree with family and friends, presuming the identified “psychosis” was, perhaps, what you, Dr. Fisher, were experiencing, at age 25.

Furthermore, there may be a problem in having a medical doctor leading such teams, in any case.

(As you well know, Open Dialogue founder, Dr. Jaakko Seikkula, is not a medical doctor. He is a psychotherapist. And, I have heard that medical doctors are kept somewhat at bay, in Open Dialogue.)

For instance: as an M.D., Dr. Fisher, you offer a useful medical “parallel” to the Open Dialogue approach to ‘first episode psychosis’ (in your allusion to Sister Elizabeth Kenny’s alternative approach to polio); but, it may be misleading – as many people (such as I) are certain, that we were *not* experiencing a ‘disease’ or ‘illness’ when in the midst of what was called “psychosis”. You may well understand and accept that, intellectually; but, I wonder: Is that frowning figure on the left, in your artful diagram, not likely to be treated as a “patient” in terrible distress – and, perhaps, at last, as one ‘needing’ medical attention???

After all, quite often, when forcing ‘medical care’ upon a so-called “psychotic patient,” psychiatrists and others will claim that the victim of such ‘treatment’ is suffering terribly underneath.

I know you sincerely wish to minimize such ‘care’; in that way, you are a rare psychiatrist – and praiseworthy; but, the graphic which you present, above, will, at the very least, prejudice the ‘treatment team’ – leading them to suspect that the identified “patient” is somehow, necessarily, miserable – as opposed to awakening; will it not?

Honestly, I detest that diagram.

Where, in that diagram, is the family system which (I presume) produced such misery, as you were apparently suffering at age 25, I wonder?

Why is the identified ‘patient’ pictured as the only sufferer?

Report comment

For the sake of providing clarity, please understand…

I say, above, that: …quite often, when forcing ‘medical care’ upon a so-called “psychotic patient,” psychiatrists and others will claim that the victim of such ‘treatment’ is suffering terribly underneath.

Hopefully, you realize what I mean there, is this:

Many who are involved in forcibly medicalizing so-called “psychotic patients” will *incorrectly* presume that, despite any appearances to the contrary, supposedly ‘psychotic’ persons must be suffering if/when receiving no medical so-called “care”; in fact, usually, the officially perceived ‘psychotic’ person will not be allowed to maintain this position, that s/he is *not* suffering terribly; and, s/he will be made to suffer – via medicalization.

Until the “patient” is made to suffer, by way of medicalization, the ‘carers’ will continue to lobby for further medicalization.

Note prominently: In my view, it is not that the ‘carers’ typically want the identified “patient” to suffer; but, they don’t want him or her to revel in the freedom of a potentially on-going ‘psychosis’ — because conventional psychiatric ‘wisdom’ tells them: any non-medicalized ‘psychosis’ will lead to disaster.

Of course, those who promote Open Dialogue well understand that such conventional psychiatric ‘wisdom’ is full of holes.

Report comment

I’ve been making comments on blogs for years, explaining that, IMO “psychosis” is unique for each individual, and that there are MANY ways a person can overcome such an episode, and move on with their life… thrive.

I’ve reached that conclusion by listening to what others have to say about what worked for them. Some good links here –

http://discoverandrecover.wordpress.com/recovery

I stand by my comment of appreciation for Dr. Dan Fisher. IMO, he’s done a lot to change the system.

Duane

Report comment

In fact, I’ve gone out on a limb to explain that, IMO “psychosis” is not ALWAYS caused trauma and/or the need to build healthier relationships… I’ve met to many folks who had underlying physical conditions that have been behind these episodes –

http://discoverandrecover.wordpress.com/2012/06/02/root-causes-of-mental-illness-and-non-drug-solutions/

IMO, whatever works, works.

Duane

Report comment

Duane,

I appreciate both of your responses (August 5, 2012 at 8:55 pm and August 5, 2012 at 9:07 pm).

Those are good links, and it’s great that, for years, you’ve been leaving blog comments which point out, experiences of so-called “psychosis” are unique for each individual.

Regarding your insistence that what is called “psychosis” is, “not ALWAYS caused by trauma and/or the need to build healthier relationships…”

Perhaps, there you were indirectly replying to my having asked Dr. Fisher, “Where, in that diagram, is the family system which (I presume) produced such misery, as you were apparently suffering at age 25, I wonder? Why is the identified ‘patient’ pictured as the only sufferer?”

You add, “I’ve met […] many folks who had underlying physical conditions that have been behind these episodes.”

Maybe we could agree, that those “underlying physical conditions” were created, in effect, by *physical trauma* (if they were truly not the result of dysfunctional social relations)?

For, I believe one can reasonably state, that: any “purely biological” cause of an apparent “psychosis” is a physical trauma; and, in any case, yes, it seems to me, that: whatever *distress* leads to and/or underlies a perceived ‘psychosis’ may be more or less the product, initially, of more or less consciously challenging (“distressing”) *biological* and/or *psycho-social* conditions.

For various reasons, by that point at which I’d posted my two comments, above, I’d come to presume, that Dr. Fisher’s sufferings, at age 25 were derived primarily from family system dysfunction.

(Admittedly, that was me being presumptuous – based on inference… the result of my interpretations, of a scattering of details, gathered from my exposure to various writings, by Dr. Fisher.) But, surely, there could have been any number of causes, which led to what he describes, as his “psychosis” at age 25.

What I came to experience at age 21.5 (i.e., that which was called, “psychosis”) was the result of whole panoply of causes (including poor diet, lack of sleep, and – not least of all – family system stressors); but, emphatically: it was not, in my view, a ‘bad’ experience – until the ‘family intervention’ that led me to be forcibly ‘medicated’ and then, for three and a half years, “stabilized” (ostensibly) by medical-coercive psychiatry.

Report comment

Jonah,

I don’t have all the answers. I don’t think anybody does.

The inter-connection between mind-body-spirit is complex. I simply believe (based on life experience, and listening to others) that people overcome adversity, they get stronger, they recover, they thrive!

… and they do so by rejecting the notion that they cannot!

In spite of years of reading, listening, learning, that’s all I really “know”.

Duane

Report comment

Dear Beyond Labels, There is much wisdom in your post. First of all, though I want to be sure I understand your perspective. So I will restate each point as I hear it and then comment on it.

You first of all state that I over generalize from my own experience and therefore most of what I say is projection.

My comment: I would agree that I am putting much weight on my personal experience, and should have made that caveat. However, I have presented this perspective to many audiences and it often resonates. Furthermore, I have interviewed over a hundred other persons with lived experience as well as treated perhaps thousands.

The point about whether psychosis is a state of a split between mind and heart. You state that is a very old concept, and that for you there was blending of mind and body.

Comment:I think both of these states may occur in monologue. I think that my diagram is simplistic. It is merely a snapshot in time, and neglects to show different phases of monologue, fails to show the internal dialogue or monologue going on inside. I do recall in the early stages of my passing into my own world of monologue, I experienced elation. There was a flood of inner, very private dialogue, which was a period of great insight. This might have corresponded to your description of blending mind and heart. But then I became frightened, and then I became the frightened figure in the diagram. Then my inner dialogue broke down into a flood of one directional frightening thoughts for which I had no answer. I had loud thoughts (which could be called voices) convincing me that everyone else was a robot, and I lost in the inner voice to answer them back.

You are concerned that my not depicting the family in the diagram and using the parallel with polio are too medical.

Comment: I am trying to move our thinking away from medical descriptions, and to that extent the question of where is the person’s family in the diagram is good. Your questions about the family raise a question about the person showing distress for the network, not being pathologized. I will need to check with the Open Dialogue practitioners. I have seen that they work to improve the dialogue within the family as much as between the person showing distress and the family. Perhaps parents have adapted to their own monologue in a way that there children cannot, luckily, do.

As far as the polio analogy, it was raised more as a caution against over treating symptoms rather causality. Instead I hoped it would show the extent to which the medicalized treatment immediately with medication actually made the problems much worse.

Report comment

Dr. Fisher,

Thank you for taking the time to reply so thoughtfully. Please excuse me as I go on, here, somewhat at length; I begin by addressing your last statement: “…the polio analogy, it was raised more as a caution against over treating symptoms…” You say this “parallel” was *not* a way to illustrate “causality”; rather, you, “hoped it would show the extent to which the medicalized treatment immediately with medication actually made the problems much worse.”

I understood your intent (“a caution against over treating symptoms”), as such; and, I *greatly* appreciate that intent; however, I do not care for the analogy, for I find it leads me to think of ‘psychosis’ as a *medical condition* – as an “illness” or “disease” – in the same way those commonly parroted “parallels” to diabetes, did, when I was first called “mentally ill” by psychiatrists, more than two and half decades ago. (Of course, you’re aware of the *diabetes* analogy – aimed at keeping psychiatric ‘patients’ on meds – how it leads one to accept the myth that s/he has a “chemical imbalance” in the brain, which needs to be ‘balanced’ by psychopharmacology, in the same way that high blood-sugar levels may be balanced by insulin injections.) I figure one could somewhat positively reframe the, “just-like-diabetes” mythology – by reference to “Type 2 diabetes”; i.e., with that more specific reference, one hopefully sees that so-called “mental illness” could possibly be ‘managed’ without use of daily meds; ‘it’ could be managed by lifestyle changes. Nonetheless, unfortunately, what remains, then, is this notion, that: one is somehow, necessarily, a medical “patient,” supposedly, indeed, battling real illness.

I prefer to drop the medical analogies altogether, as I do *not* believe these so-called “psychoses” are illnesses; in fact, they are (in my view) more like dreams, being natural vehicles for bringing about healthy change. (Though, they can seem as though *nightmares* for some people; such became the case for you, at age 25, it seems.)

Regarding your first statement (on generalizing and projecting): Yes, you do generalize, based on your own experiences; that’s natural and understandable; we *all* do that, to some extent, I believe. Everyone does. But, you are *projecting* once you aim to coin “a new understanding of ‘psychosis’”; defining (and, perhaps, redefining) such an ultimately elusive – *key* – experiential concept as “psychosis,” according to your own experiences, is problematic, in my opinion; you are opening a kettle of worms, that way. (And, that you do so is no small matter, I feel; for, you are a foremost leader of various dialogues, based on Open Dialogue techniques; your position of authority, as such, becomes very persuasive; many will not think to question what you’re saying, in these regards; indeed, all you’re getting is praise – despite the fact that, in your diagram, you’re parading this ‘heart-mind split’ stereotype, that’s very objectionable, to many, such as I; it’s why I feel your “new” definition/s of “psychosis” must be questioned.)

But, you defend yourself, saying, “I have presented this perspective to many audiences and it often resonates. Furthermore, I have interviewed over a hundred other persons with lived experience as well as treated perhaps thousands.”

What you’re offering there is, no doubt, true; I’m sure it’s a verifiable fact; but, it is *not* particularly reassuring to me; all it tells me is that you’re successfully surrounding yourself with admirers. (In fact, I admire your ability to attract admirers; yet, my sense is, that: as an admired authority, on these matters, your views are being applauded, and – by this point – not thoroughly questioned.)

You say, “my diagram is simplistic. It is merely a snapshot in time, and neglects to show different phases of monologue, fails to show the internal dialogue or monologue going on inside.”

OK, so, then, perhaps, you should indicate that: the diagram is a picture representing your own past experience, at one moment in time (when you were 25 years old), when you were experiencing something that was called “psychosis”; and, it is certainly *not* indicative of everyone’s so-called “psychosis” experience/s.

Perhaps, in your view, the diagram indicates a *type* of so-called “psychosis” experience, which most calls for help, from others?? …If that’s the case, I wonder: Does that image (in and of itself) do anything to persuade us, that immediate medicalization is truly unnecessary??? (That is to say: I think it may fail to function, in accord with that fine intent, which you aim to convey, in your polio analogy – that, “extent to which the medicalized treatment immediately with medication actually made the problems much worse.”)

Regarding your description of your experience, at age 25 (thank you for sharing those experiences): You say, “…I became frightened, and then I became the frightened figure in the diagram. Then my inner dialogue broke down into a flood of one directional frightening thoughts for which I had no answer. I had loud thoughts (which could be called voices) convincing me that everyone else was a robot, and I lost in the inner voice to answer them back.”

Those were unlike my own experiences, at age 21.5, of what was called “psychosis”; prior to then, I had been somewhat (*not entirely*) ‘stuck in monologue’; I was never completely stuck; but, eventually, I acted out – perhaps, *partly* in attempt to avoid getting stuck? I threw a stack of cheap plates (one-at-a-time) at a garage door, in my parents’ backyard. It shocked people. They viewed me as ‘crazy’; and, people were, thus, behaving in very reactionary/programmed (one might reasonably call them ‘robotic’) ways; from that point, forward, for everyone spun into a panic mode, bent on getting me “hospitalized”.

Did I think of those people literally as robots? No. (I am wondering if, in the midst of your crisis, you suspected that people were *literally* robots?)

But, I was in an ‘altered’ state; perhaps, I was necessarily in monologue, because no one would listen to me? (Everyone was more or less terrified.) I was viewed as delusional. However, I was *not* delusional; and, in months leading up to that time, really, I was not – and, I was *never* completely – stuck in monologue. I had been somewhat minimally stuck, at that point, at which I threw the plates; but, in any case, I had, as well, released myself entirely from much routine; really, had done so, altogether; life itself had become exceedingly interesting; I’d been coming up with*many* personal revelations, in the weeks leading up to that point; in fact, I was in full dialogue mode – internally and externally – when, the day before I threw the plates, I experienced what, in retrospect, I know was a kundalini experience; I related the feeling, at that time, to what I presumed was ‘psychosis’ (at that time); but, I was not at all scared by that; for, the idea of ‘psychosis’ did *not* scare me in the least (not at all, really); but, as I described my experience to others, they became scared; and, now (so many years later), I am aware, that *many* people (such as yourself) describe “psychosis” as more or less very scary.

What was scary for me was how people reacted to me. (And, what would be ultimately terrifying was how I was ‘treated’ by psychiatry, from that point, forward – i.e., how I was *forcibly* medicalized.)

I do not know if you were ever forcibly medicalized; but, to some extent, you should be able to relate to what I experienced; for, I can relate to you, as you write, “This state of mind is technically called a hypnagogic state, which is a state of consciousness between being asleep and awake. I recall being in that state of mind for a prolonged period when I was in psychosis. It was like a waking dream. It was as if my dream world was spilling into my waking world. At first it was thrilling. I felt at one with the world about me. Temporary periods of such waking dreams can be very revealing and may be the states of mind of greatest creativity. They may be the periods of artistic creation and of creation of an integrated self. However, if they are accompanied by panic by oneself and the people around one then those states of mind can result in psychosis.”

My one difficulty with what you’re saying there, in that paragraph, is this: You conclude by defining “psychosis,” as that which comes from extreme fear of the hypnagogic state (again, I point out, emphatically: I never feared ‘psychosis’; others came to fear ‘it’ – as ‘it’ supposedly manifested, in me).

Why do you define “psychosis” that way even as you begin, by describing “psychosis” as part and parcel of a creative experience. (I am really opposed to this notion, that ‘psychoses’ must be scary.) Do you mean to say, that it can be a lovely thing and/or a scary thing?

About your saying, “I had loud thoughts (which could be called voices) convincing me that everyone else was a robot, and I lost in the inner voice to answer them back.” With all due respect, I wonder: could you not understand “robot” as a *metaphorical* description (i.e., as referring to people who are behaving in ‘automatic’/’programmed’/reactionary ways)??

I would love to know more about how that “robot” idea existed in your mind. But, in any event, it seems to me, from what you are saying, that your *fear* was your undoing. You can tell me if I’m wrong. (Surely, fear became part of my undoing – after the momentary impetuousness, of breaking those plates; but, I had no fear of my own mind – none whatsoever; rather, I feared the limited ability of others, to understand and appreciate what I was experiencing; and, by extension, I feared the kind of ‘treatment/s,’ that they would, in their ignorance, likely force upon me.) But, the main question I would put to you: what was it, exactly, that scared you the most? Were you scared you might harm yourself or others? (I know that’s a very personal question, so I don’t necessarily expect an answer.)

Though I was accused of being a danger to myself, it was absolutely *not* true. On the contrary, I was a danger to no one; and, I became scared only as it became clear to me, that everyone wanted me medicalized; I feared being made into a “mental patient”; and, those fears were ultimately *very* well founded – not at all unreasonable.

In my roughly three and a half months of “hospitalization” (endured in the course, of my three and a half years, as psychiatric “patient”), never was I the *least* bit well understood by anyone; I was simply too heavily ‘medicated’ to be understood.

Finally, for now, this last curiosity: Near the top of your post, you say, “Then, when I could not return to consensual reality, I was terrified.” I wonder, why did you want to return to consensual reality? (And/or, what do you mean by “consensual reality,” in the context of that sentence?)

Again, thanks for your reply.

~Jonah

http://twitter.com/beyondlabeling

Report comment

Thank you for the excellent article, as well as for the insights from those making comments. The study of Buddhism as well as daily meditations helped me in my recovery journey. Allowing yourself to feel emotions without being overcome by them – instead of being frightened,ashamed, or trying to either run away or cling to them – is a much healthier way to experience life. I began meditating about 17 years ago after reading – In The Artist Way by Julia Cameron – that meditation can help one become more creative – At about the same time I read in The Journal – which was published by California NAMI that racing thoughts was a symptom of bipolar, which was one of my diagnosis, the other being PTSD. I had racing thoughts for as long as I could remember, at least since age 5 or 6. I began meditating every time my thoughts began to race, and then daily for at least 10- 15 minutes. Within 6 or 8 months, I realized that I was no longer having racing thoughts. During this time I was also receiving cognitive therapy, which helped me to relearn responses to stress. My journey through madness helped make me a better person, and while it is a journey I do not recommend to anyone – for those who find themselves on the journey, please try to consider it as a valuable learning experience – and work to make the mental health system first rate by sane, compassionate and even joyful.

Report comment

Dan-

First of all, thank you for doing this work and putting it out for everyone to learn from. I find your ideas amazing and believe they have the potential to save lives – I hope I live to see the day when this approach is the prevailing paradigm, and see the end of current ignorant and destructive practices. I’ve lost my life to being cast alone at a young age into the system – drugged, not hugged. I dream of nothing more or less when this kind of “treatment” is seen to be as just as barbaric as, or worse than, lobotomy.

From my own experiences, which aren’t “psychosis”, but rooted just as deeply and have been equally destructive, I have found that being in relationship with peers reduces my tendency to have painful inner dialogues, which for me tend to be automatic negative thoughts and derogatory self-judgments.

When I have worked with people who experience psychosis, I find that acknowledging the core of emotional truth within what psychiatrists call “delusions” is remarkably helpful. All of the people (labeled delusional) who I’ve been fortunate to work with – experienced a change in their belief systems in a reaction(or series of reactions) to events that were life threatening or highly sense-of-self threatening traumatic experiences, mostly the latter category.

Being supportive and non-judmental and allowing people to explore their “different truth” – actually an emotional reality, not a literal one, based on real traumatic events and unexperienced feelings. I have learned “the hard way” that feelings must be experienced, not just analyzed, or they explode. For some of the people I with, that explosion led to a seismic change in their perception of some aspect of “self”, which psychiatry calls “delusional.”

Exploring and allowing a person to enter a dialogue – with me, or anyone who listens carefully – about the emotional truth of the “delusion” reduced and, for most people, over time, eliminated their tendency to be overly focused on the disturbing idea – i.e. “delusion.” By allowing people to explore their feelings and experiences without ever challenging their perception of reality, even supporting them in the fact that there is a truth to what they had been told was “a symptom of psychosis” helped them escape obsessive monologue and grow in ways that amazed me and of which I felt honored to be a part, the lesser part, because the person did all the hard work, I was just there to encourage and be a witness to their truths.

How would you propose helping people who have experienced very early trauma including trauma inflicted by the mother or a sibling (close in age) that compromises a person’s ability to develop and/or maintain “heart-to-heart connections”? It seems to me that many people with “psychosis” (even people who experience extreme states without “psychosis”) struggle terribly trying to develop authentic interpersonal connections, and then experience repeated rejection. How can these folks enter into dialogue – much less the “heart to heart connections” that create an environment for the healing potential in the transition from isolated monologue to dialogic relationship. I hope I have understood your model properly – in asking this question…

Most of all, I hope that, as a community, and as a society we find ways to make this kind of help available to many people – someday, everyone.

The power of people in the mental health professions continues to grow and the drug companies earn their highest profits from pushing psychotropic drugs – seemingly harmless, and extremely addictive in that experiences post-withdrawal can be worse than the states that prompted an initial prescription. I am very concerned for the generation who are currently children – and are being started on these psychoactive drugs at young ages with little to no research on their effects on brain development.

What happens when 50% of our population has real chemical imbalances based on years of taking these drugs.

So, I feel an urgency about forming practical plans to gain proof of evidence-base and start to implement this type of “non-treatment”, treatment. Please let me know if I may be of assistance. For now, I prefer to remain anonymous online. You have my permission and blessing to ask Bob for my registration information. Best of luck and keep it up…

Report comment

I agree with Louise Gillet that prolonged sleep deprivation has something to do with “psychosis” and at least in my experience interferes with logical thinking, brings stresses to the fore which need to be delt with etc. It seems also to errode the boundaries between dream and reality; in this context the book “Dreaming Reality” by Joe Griffin and Ivan Tyrrel is extremely interesting and, I think, they are putting the finger on to something that should be looked into further.

Report comment

Hi Dan,

This is a heartfelt and fascinating blog. I think what I love the most about all of your writing is your everlasting and tireless search for an understanding of the complexities of the interrelationships, both personal and political, which lead to states of emotional turmoil, how we are treated in our society when we have been labeled “mentally ill,” and how we can improve the world for everyone. In the same way that it takes a village to raise a child, it is important that we all share our thoughts and memories. Each person’s experience is unique although there are certainly many common themes and stories of atrocities within the system.

For me, I really cannot remember being psychotic as I have lost any memory of those months before I was hospitalized. And then, I was so badly treated with ECT and medication and seclusion that I honestly think my silent behavior (probably viewed as psychotic – and labeled schizophrenic at the time) was a healthy response to the violence against me. I was trying to survive with every bit of energy I had within me; I was also trying privately to figure out how in the world I could escape.

I was not talking to anyone, but I really do not view this as psychotic. Definitely monologue. I was only talking silently to myself which was the only intelligent way I could figure out to behave. I took control of my voice even though I felt totally out of control and under everyone else’s control. I also stopped eating, another way to feel in control.

I am not at all certain that Open Dialogue would have worked with our family. I had been the identified patient, and all parental emotional doors had been firmly shut tight for years. It would have had to start when I was a young child for the frozen family system to melt in the way necessary for true healing of all family members. In the end, I still feel that I was better off on my own. I guess I feel that way because I was lucky, lucky to have survived.

I love the parallel with polio and Sister Elizabeth Kenny! I had just such a political and personal hero in my life as an adolescent at the time. My Sister Kenny was a psychiatrist I met in the final days of being locked up in institutions for three years. He was the first and only person to look into my eyes with a twinkle in his eyes and a warm smile. He simply said, “there is nothing the matter with you that was not caused by your ‘treatment’ in the hospitals.” He took me off all medication. He gave me hope. Whatever you might call it, Open Dialogue or whatever, he reached right into my heart and soul and believed in me in a way that no one else did. He essentially mothered me in the most beautiful sense of that word. He took my hand and he brought me back to life. It did not happen overnight, but it was a slow and steady process of building trust and just talking and listening to each other.

I have been absolutely fine for years and years.

***********

Thank you, Dan, and to all of the other posters here.

Report comment

One or two more thoughts, out of many swirling around in my head because of all that this blog brings up for me:

My “psychotic” behavior (I did not perceive it as psychotic) was not pleasant or euphoric as I sometimes hear others describe. I felt trapped inside my head with my thoughts. It felt as though I was on a fast-moving train that I could not get off. I think part of the reason my behavior persisted for so long was because of my rage and feeling of helplessness and need to grasp whatever control I could to keep myself alive. The interesting thing, and what I think brings so much hope for others, is that it only took one gentle, kind person to get me out of that lonely space.

Everyone needs to understand that kindness and compassion are the most powerful healers of all.

***********

Report comment

Taconic, Thank you for your insights and sensitivity. Your life is a testament to the power of even one kind, compassionate person when we are deep inside our own well defended self. Your remaining so long inside due to rage points to the two faces of altered states. They can be a life saver or if experienced in a hostile environment they can be an existence of no exit. Hopefully we can find ways that people can access the wisdom and healing of those altered states without getting trapped in rage or fear.

As far as Open Dialogue for monological families, I too share concerns.Perhaps the families in Finland are not as rigid, nuclear, and hierarchical as many families such as yours and mine are here. One way to modify work with such a family might be the addition of a peer to the Open Dialogue team. They have not done that in Finland, but it may be an important adaptation here, both because of the rigidity of some of our families and the eagerness of peers here to assist in such situations?

Report comment

If I recall correctly, the affected person is the one to identify whom s/he wants to involve in the dialogue. It definitely occurred to me that having the wrong person there could be hugely detrimental, but Will Hall did an excellent demonstration (I got to be his “co-facilitator!) which put my concerns mostly to rest.

Report comment

This is a concern of mine also, and I have heard it raised often, especially by women who experienced abuse and trauma in the family. One aspect to consider even if the person is being asked who should be present, is, what happens if there is really no one you can think of? Or if you are tempted to involve the family because you want their love, but you get more heartbroken? It’s a lot to ask of any process or group of people to create a space to heal all of that. Maybe the starting point needs to be, not an assumption that you need an open dialogue with a bunch of people in your life or whom you want in your life (which would put pressure on the person to channel their wishes for healing into that framework) but, what do you need? Do you need to heal? Do you need solitude supported materially and practically with kindness? It’s also “documented” and known to many of us from experience that solitude can be a healer. This could also relate to the question above from Mad Ann, who asks what about people who have been too traumatized to create the heart-to-heart connection? There are many paths, we need at minimum connection in the sense of kindness and perhaps respect, combined with a good-faith empathy…. but people need to proceed in their own way in figuring out the life mysteries including the mysteries about connection and solitude.

Report comment

Thank you, Dan. That is an interesting suggestion that a peer be included in the Open Dialogue team. Perhaps I might have been able to identify and ally myself with such a person who had lived through similar life experiences to my own. But, with my family, I do believe it would have had to start quite a while before I finally became so completely depressed, probably in early childhood before the family system became so locked in place. The goal, I hope, would be to offer this to families before anyone was hospitalized. Once I was locked up, my feelings of abandonment were so deep that I doubt I could have tolerated sitting in the same room with my family no matter who else was there. It would have taken an extraordinarily gifted and kind and creative person to accomplish that. Even with my wonderful doctor, I never gave him permission to talk with my family, and he respected that. I needed to be truly free from those who ultimately saw me as the “sick” one in the family.

Report comment

Thank you for posting this article ,which to me was a window to sanity.

I felt so moved by the posts of the people who so clearly highlight the cruelty and indifference one can experience by some mental health proffessionals , after having been labeled as ‘psychotic’.When one feels so vulnerable ,threatened or traumatized and needs so much ‘to be hugged but instead of that becomes drugged’ ,and degraded to a ‘mentally ill patient’.

I suffer from ptsd ,,after an extremely abusive relationship ,which escalated to a follie a deux(induced psychosis).

Therapeutic treatment for me was of little support because it was so supperficial that it never met the core of the pain and dread of my experience.My trauma and ’emotional truth’ was met as delusions which had to be medicated away ,instead of expressed and explored. Indeed I felt that I was not offered a healing heart to heart dialog,but I havent given up to find it and hope I will.

In part I still suffer from flash backs which close me some hours of the day in this monologe.Writing and drawing has been a very helpful way in my recovery process as also sharing my feelings and thoughts with friends.

I so much agree with what the drawings in this article point out! It is this sharing of the lonely ,inner,painful and sometimes scary monolog to a heart felt dialog ,which is the essence of all healing.

Sometimes ,I think that this altered state of consiousnes called psychosis is a healthy reaction to an such a painful experience or situation in life ,which overwhelms ones capacity to emotionally cope with it.

Medication can be helpful ,but in long term I am afraid that it blocks the emotional expression and deeper awareness of what the soul wants or tries ,sometimes desperatelly to express and communicate through this ‘psychotic’ experience.In a way I come to think that ‘psychosis’ is not an illnes but the result of a failure to communicate and share ones inner emotional reality to the Other, sometimes just because the other is rejective instead of empathic,or simply absent either emotionally or fysically.

Personally , I felt that I had found a retreat to my inner monolog of pain because I felt so rejected and did not found this heart to heart dialog when as most I nedded it.The support of some of my friends , art, and sharing with people who had similar experiences

was if great help.As also Hope.

Thank you for this blog and the opportunity to share !

Selena

Report comment

This theme is so personal and yet so much a theme impacting everyone. I too find myself at times not represented and misunderstood by voices of recovery. But on the other hand I also know that without the sharing of other people’s experiences ( as different as they might ev be from mine) I could find hope over and over again. Being lost in my own thinking and feeling for long stretches in my life I neede a people who truly believed in me to get back to regain balance in my life.

I sat in a meeting today listening to the language and arguments of representatives of our community mental health and crisi supports and got very, very sad witnessing the very removed take on how to “treat” people in “crisis”.

Report comment

Sabine, I too sat in such sad team meetings for many years, missing

the essential ingredient you cite, people who believe in us when we had

lost belief in ourselves. I believe there is increasing awareness that

Recovery or discovery is real and will increasingly reach to each person.

Report comment

Disorientation was the condition that sent me to my first hospitalization, at 15 years old, which lasted 2 months.

How bad things were, including the neglect (main ingredient), which allowed my condition to become so severe!

Disorientation was not the problem; it was the effect of it’s cause. But things have to get that bad before people will truly pay attention and take (give) care. We are EXPECTED to tolerate and endure. It’s only when we begin to break down that we BECOME crippled, handicapped, disabled, mentally ill people.

Report comment

I’ve suffered Amphetamine psychosis twice: both times I was saved by the love of a good Woman of whom I was dating at the time. The ability to remain connected and loved at the same time is key towards recovery.

While my ability of objective reality ruinously disintegrated in to oblivion I knew I was in a safe place and not in danger. It is important to record here, I always retained the ability to differentiate right from wrong. Just because people break, doesn’t mean they lose the ability to have good moral value!

I have been able to fully recover from extreme states because of loving Women in my life… Based on my embedded research, I wholeheartedly recommend dating intelligent nice empathetic people who serve as advocates and guides back to reality.

~Snowy

Report comment

Your comment makes me think of Celine Dion’s new song, Loved Me Back To Life

http://youtu.be/4f5KuRXtjeE

Report comment

To recover is wonderful. To fail sad.

I listened to a philosophy talk on PBS radio discussing who “I” was. Was I my consciousness, my memories, my mind, my brain.

What if my consciousness was unconscious, my memories false, my mind unreliable, by brain in some state of failure. Then, who was I? Who was listening to the radio, trying to make sense of what was being said, trying to apply what was heard to my experience, my life, my sense of self; and who were all these others around me?

I have seen the Hubble deep field records. I know there is more life, more variations on life (and death) then dreamt of in all philosophy. I know we die ourselves to sleep every evening if we are lucky, and reassemble what we think we are all mornings when we wake. I am amazed when what we think we are is recognized by compatriots and comrades and left called reality by all the others that we meet those same mornings, still recognizable and agreed on afternoons, and surrendered every other evening of the world. I think we are the same from day to day enough to pass for sane in our agreed upon reality.

Yet something tells me there is something new I never knew before about this morning, some surprise in store.

I hope I am still going to be around each next day, and I try to never think about how vaporous and evanescent all this life stuff, content and container, all I call myself will be.

Conscious or unconscious, I stayed real enough to see these words spelled out electronically reaching through new media to eyes and ears I’ll never know, who’ll think they know me by them.

Report comment

ucompsyche:

Good Stuff! Ever read Assagioli’s work? His definition of the “I” and personal pyschosynthesis are incredible thoughts too. His definition of the ‘self’, and the ‘superconscious’ towards a path of enlightenment are really cool ideas. I think it expounds on Freud and Jung in a really healing and intellectual way.

One of the most fascinating things I learned from Assagioli’s work was his theory about integrating ‘sub-personalities’ and the necessity of a strong ego to be in tune with the spiritual realm.

Peace be with you,

~Snowy

Report comment

Thank you, I looked Assagioli up and found Wiki entries and the “project”. I will (Ha) spend some time on this.

Report comment