BACKGROUND

On December 8, I received the following question from a reader: (The subject matter is the controversial CAFÉ – Comparisons of Atypicals in First Episode of Psychosis – study. This was the study in which Dan Markingson committed suicide.)

“It appears that there was no head-to-head with a control group taking a placebo pill. Nor was there a control group featuring ‘old’ types of ‘antipsychotic’. If that was the case then it is very poor study. If you are just looking at 3 ‘new’ subtypes of a ‘new’ class – then what on earth can you hope to show from the data?”

I started to write a response, but the subject is complex, and my response became the following article:

Any discussion of CAFÉ must begin with a review of CATIE (Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness).

CATIE was a randomized trial funded by the US government (NIMH). It was written up in three phases: Phase 1 (Lieberman J et al, 2005); Phase 2 Part a (McEvoy JP et al, 2006) and Phase 2 Part b (Stroup TS et al, 2006); and CATIE Phase 3 (Stroup TS et al, 2009). CATIE’s purpose was to compare old neuroleptics with new neuroleptics. There was no placebo. This reflected the belief/assumption that the efficacy of neuroleptics generally had already been established. The researchers compared the old drug perphenazine with the second generation neuroleptics olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone. The conclusion:

“Olanzapine was the most effective in terms of the rates of discontinuation, and the efficacy of the conventional antipsychotic agent perphenazine appeared similar to that of quetiapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone. Olanzapine was associated with greater weight gain and increases in measurers of glucose and lipid metabolism.” (Phase 1, p 1209)

So, a kind of mixed result; but notice that quetiapine was shown to be no better than the old drug.

In CATIE phase 2, clozapine was introduced. One of the findings was:

“At 3-month assessments, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale total scores had decreased more in patients treated with clozapine than in patients treated with quetiapine or risperidone but not olanzapine.” ( Part a, p 600)

and

“…risperidone and olanzapine were more effective than quetiapine and ziprasidone as reflected by longer time until discontinuation for any reason.” (Part b, p 611)

Again, a mixed result. Clozapine is most effective but known to have even more serious adverse effects than other neuroleptics. But notice again that quetiapine isn’t looking too good.

CATIE also had a placebo-controlled arm that addressed the use of neuroleptics in “treating” aggression and agitation in patients with Alzheimer’s Disease (CATIE-AD, Schenider et al 2006). Even here, quetiapine didn’t do so well. It had the lowest “improvement” rate, though the differences were not statistically significant. The researchers also noted that:

“Adverse effects offset advantages in the efficacy of atypical antipsychotic drugs for the treatment of psychosis, aggression, or agitation in patients with Alzheimer’s disease.” (p 1525)

It was also found in CATIE Phase 1 that the individuals who had received quetiapine had the highest rate of hospitalization during the study. The comparative figures were:

Olanzapine – 11%

Quetiapine – 20%

Risperidone – 15%

Perphenazine – 16%

Ziprasidone – 18%

(Table 3, p 1220)

These differences were statistically significant at the 0.001 level (i.e. there’s less than one chance in a thousand that the differences could have occurred by chance).

CAFÉ

Which brings us to CAFÉ, a multi-site study of neuroleptic treatment of first episode psychosis, funded by AstraZeneca, manufacturer of quetiapine (Seroquel). CAFÉ was written up in two parts in the American Journal of Psychiatry. CAFÉ has been criticized as little more than a marketing ploy by AstraZeneca to rescue their baby from the CATIE fall-out.

There were two main hypotheses:

“…that quetiapine was not inferior to olanzapine or risperidone in the rate of all cause treatment discontinuation in early psychosis patients.” (p 1050)

and

“…that the three agents would be equivalent in their effects on various neurocognitive measures.” (p 1061)

The researchers concluded:

“Olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone demonstrated comparable effectiveness in early-psychosis patients, as indicated by similar rates of all-cause treatment discontinuation.” (p 1050)

and

“Olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone all produced significant improvement in neurocognition in early-psychosis patients. Although cognitive improvements were modest, their clinical importance was suggested by relationships with improvements in functional outcome.” (p 1061)

So, quetiapine is just as good, as measured by rates of treatment discontinuation, in early stage psychosis as the other second-generation neuroleptics. The rate of treatment discontinuation, however, is a fairly minimal outcome criterion. The usual rationale for using it in these kinds of studies is the assumption that it is inevitably associated with poor outcome generally. This assumption has been critiqued widely in recent years, but is still generally accepted by psychiatrists.

But the most serious critique launched against CAFÉ is that the researchers administered the rival drugs at reduced dosages. Olanzapine and risperidone were administered at about 60% of the CATIE dose, while quetiapine was administered at about 90% of the CATIE dose. Here’s what the researchers wrote:

“Previous studies suggesting that first-episode patients receive therapeutic benefit from antipsychotic doses lower than those required for chronic patients and that first-episode patients develop unnecessary extrapyramidal side effects at higher doses led us to use lower dose ranges of olanzapine and risperidone in this study than those used in the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention effectiveness (CATIE). However, given quetiapine’s low extrapyramidal side effects liability, we expected that the quetiapine doses used in CATIE would be tolerable in our study population.” (p 1058)

This seems questionable. Neuroleptics, at least initially, reduce agitated thoughts and behavior. And the higher the dose, the greater the “improvement.” The authors themselves acknowledged this interpretation:

“This may have been a factor in the comparable effectiveness demonstrated by quetiapine. In the CATIE phase 1 and phase 2 schizophrenia trials…higher mean modal doses of olanzapine and risperidone but similar mean modal doses of quetiapine were used; in these trials, olanzapine and less consistently risperidone proved to be more effective than quetiapine. It remains an empirical question whether higher doses will improve the relative effectiveness of quetiapine in chronic patients.” (p 1058)

But this is buried in the text of a 20-page article. As mentioned earlier, the article is written up in two parts in the American Journal of Psychiatry, 2007 (p 1050-1060 and p 1060-1071). The above quotes appear on page 1058, but are not reflected in the conclusions.

The authors’ assertion of “low extrapyramidal side effect liability” for quetiapine is also of interest. Firstly, they cite no reference in support of this assertion. Secondly, CATIE had reported the following percentages for extrapyramidal effects: olanzapine 2%; quetiapine 3%; risperidone 3%; ziprasidone 4%. The actual numbers are too small to draw firm conclusions, but there is nothing to suggest that quetiapine has a particularly low liability.

Another item of interest that was buried in the text, but did not appear in the conclusions, was:

“A total of 18 serious adverse events occurred, four in the olanzapine group and seven each in the quetiapine and risperidone groups. These events included two suicide attempts and one alleged homicide in the olanzapine group, two completed suicides and one case of suicidal ideation in the quetiapine group, and one suicide attempt in the risperidone group.” (p 1057)

Further indications of the researchers’ agenda are suggested by the following quote:

“Our findings in this study suggest that the effect of quetiapine on cognition may be as beneficial as that of olanzapine or risperidone, and thus this agent may be another evidenced-based alternative for clinicians who focus on cognitive outcomes. (p 1069)

Even one of the primary conclusions was tenuous. In the second part of the write-up, as mentioned earlier, the authors had concluded:

“Olanzapine, quetiapine and risperidone all produced significant improvements in neurocognition in early-psychosis patients.” (p 1061)

Buried in the text, however, on page 1069-1070, they wrote:

“In this study, patients with early psychosis who demonstrated cognitive improvement at 52 weeks also demonstrated functional benefit in social and occupational domains, which suggests a functional relevance for cognitive improvement. One caveat to this promising conclusion is that given the high dropout rate in this study, these data apply only to the patients who were able to stay in treatment and complete comprehensive assessments for 52 weeks, a group that comprised only 20% of the original sample.” [emphasis added]

MEASURES OF EFFECTIVENESS

As mentioned earlier, the outcome criteria that were highlighted in the conclusions sections of the two papers were: rate of treatment discontinuation and improvements in neurocognition.

However, various other items were assessed during CAFÉ that might usefully have been included in the papers’ conclusions. In fact, the authors stated:

“Efficacy was measured in two domains: 1) psychopathology and 2) social and occupational functioning. Psychopathology was assessed by the PANSS, the CGI, and the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia . . . Social and occupational functioning was assessed with the Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale . . . ” (p 1053)

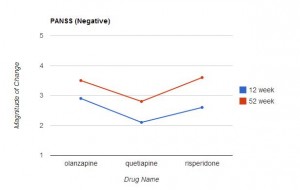

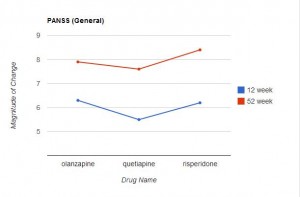

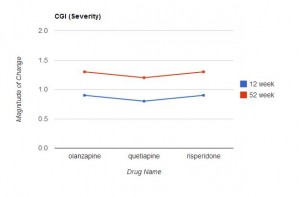

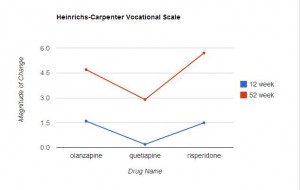

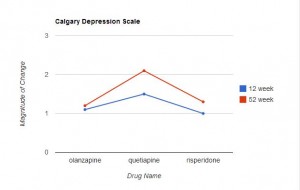

Measurements on these scales were taken before the study began, and at 12 and 52 weeks. The results are presented in Table 2 (p 1052). (Click on the image below to see the full-size table.) This is a rather complex table, and comparisons across the three drugs are not easy. For this reason, I restructured and graphed the data below.

In Table 2, an improvement in some of the scales is indicated by a negative number, in other scales by a positive number. For ease of comparison, I eliminated the signs and focused only on the magnitude of change from the baseline value. In each graph the direction upwards on the page indicates more improvement from baseline. As can be readily seen, the level of improvement with quetiapine is lower (at both 12 and 52 weeks) than with olanzapine or risperidone in 6 of the 7 scales. This difference is marginal in the CGI Severity Scale, and only reached statistical significance with the PANSS positive symptoms scores (and this was mentioned in the abstract), but the fact that quetiapine fared worse on 6 of the 7 variables seems noteworthy.

This is especially true in that the six scales addressed here are precisely the measures that would be of particular interest in the assessment of treatment effectiveness for psychotic thoughts/behaviors. In fact, CATIE used the PANSS positive and negative scales to assess effectiveness. Since the entire purpose of the study was to compare the relative effectiveness of these drugs, it’s difficult to find a valid reason for not presenting the relative effectiveness data more clearly

DISCUSSION

The big question is: was CAFÉ a piece of genuine scientific research; or was it a marketing exercise bought and paid for by AstraZeneca in an attempt to rehabilitate their drug quetiapine (Seroquel)? Obviously arguments can be made on both sides, but here are two factors that may have some bearing.

1. AstraZeneca funded the study.

2. There were a total of twelve authors listed on the two write-ups. All but three declared a history of financial ties to AstraZeneca. Of these three, Dr. Lieberman acknowledged that he had worked for AstraZeneca as an unremunerated consultant. Dr. Sweeney declared only the funding for the present study (he was lead investigator), and Dr. Gu declared no ties. Two of the authors, Dr. Lazarus and Dr. Sweitzer were employees of AstraZeneca, and both held stock options. (p 1059 and 1070)

The importance of these kinds of funding issues was highlighted in a study of head-to-head comparisons of second generation neuroleptics by Heres et al (Amer Jour Psych 2006). These researchers found:

“In 90.0% of the studies, the reported overall outcome was in favor of the sponsor’s drug . . . Potential sources of bias occurred in the areas of doses and dose escalation, study entry criteria and study populations, statistics and methods, and reporting of results and wording of findings.”

DAN MARKINGSON

There were two completed suicides in the study, both in the quetiapine group. One of these was Dan Markingson. Dan’s inclusion in the study has been the subject of considerable controversy. His mother, Mary Weiss, stated that she saw his condition deteriorate markedly during the period in question, and that she made repeated attempts to have him removed from the study and taken off the drug. It is also reported that she alerted the study coordinator to the danger of homicide or suicide. Her protests were not heeded. Recently, thanks largely to the persistent efforts of Carl Elliott, the Faculty Senate of the University of Minnesota has voted to commission an independent inquiry into the circumstances of Dan’s death. However, on December 11, Eric Kaler, President of the university stated in a press interview that the inquiry will only be looking into the university’s review procedures and that it will not be a review of Dan Markingson’s death. This announcement, predictably, has re-opened the controversy (subsequent letter from University of Toronto).

THE BIG QUESTIONS

Why did the research team at the University of Minnesota’s Department of Psychiatry not take protective action in response to Mary Weiss’s warnings concerning her son Dan?

Did they discuss these concerns, and, if so, is there a record of these discussions?

Was an assessment made of Dan’s suicide potential in response to Mary’s expressions of concern? If so, what was the result of that assessment?

On which site(s) did the other suicide and the three suicide attempts occur?

Was the decision-making concerning Dan influenced by the desire to portray quetiapine in as favorable a light as possible? In particular, was the decision not to hospitalize Dan influenced by the fact that quetiapine had fared so poorly in CATIE on the hospitalization measure?

With regards to this last point, there is, I suggest, a pressing need to separate and publish CAFÉ’s relative hospitalization rates for the three drugs. This information was not published in the study write-up, but presumably would still be available in the research files.

It is also important to investigate the question of informed consent. In the study write-up, the authors state that:

“…written informed consent was obtained from the patients or their legally authorized representatives.” (p 1051)

It has been suggested that Dan Markingson was incapable of providing informed consent at the time of his enrollment. Carl Elliott has written:

“When Mary found out that Dan had been recruited into the CAFE study, she was stunned. “I do not want him in a clinical study,” she told Olson [Stephen C. Olson, MD, one of the researchers]. Just a few days earlier, Olson indicated in a petition to the court that Dan was both dangerous and mentally incapable of consenting to antipsychotic medication. How could he now be capable of consenting to a research study with the very same antipsychotics—especially when the alternative was commitment to a state mental institution?”

A complicating factor here is that AstraZeneca paid the University of Minnesota $15,648 for each person they enrolled in CAFÉ, and it has been suggested that this financial incentive might have clouded the researchers’ judgment with regards to the ability to provide informed consent.

At the very least there are unanswered questions. Was Dan capable of giving informed consent? Was his “consent” coerced in any way?

It is now over nine years since Dan’s death. It is high time that these questions were addressed in a serious and impartial manner.

* * * * *

This post also appears on Phillip Hickey’s website, Behaviorism and Mental Health

CATIE/CAFE, AstraZeneca wouldn’t mean to get people mixed up between these studies would they?

Report comment

Well, at least CAFE sounds like it’s a study on the same level and of the same kind as CATIE. “CATIE said this, but then we got a newer study CAFE ..”

Report comment

Robb3,

I hadn’t thought of that, but now that you say it…! Personally, I have some difficulty disentangling the various acronyms.

Report comment

My comments come from my personal experience. From my lived experience. From 1974 – 1994, I was on over 40 different psychiatric drugs. Yes, the drugs made me suicidal, and crazy, and really, they did more harm than good. I’m not alone. But, I think we need to call it for what it is – GENOCIDE, and HOLOCAUST. It’s obvious to me, that Astra-Zeneca has created a business model that doses people with drugs, for money. For profit. And, like any other business, it wants to grow. How does it grow? By putting more people on more drugs. It’s that simple. It’s so simple, that nobody can see it for what it is – Genocide, and Holocaust.

Report comment