On August 19, 2014, the Annals of Internal Medicine published a paper titled Atypical Antipsychotic Drugs and the Risk for Acute Kidney Injury [AKI] and Other Adverse Outcomes in Older Adults. The authors were Joseph Hwang et al, and the study was conducted at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences in Ontario, Canada. The primary funding source was the Academic Medical Organization of Southwestern Ontario. The principal investigator was Amit X. Garg, MD, PhD, a kidney specialist at the London Health Science Center and the London Kidney Clinical Research Unit in Ontario, Canada.

Here is the authors’ conclusion:

“Atypical antipsychotic drug use is associated with an increased risk for AKI and other adverse outcomes that may explain the observed association with AKI. The findings support current safety concerns about the use of these drugs in older adults.”

Context

By way of background, the authors point out that each year “…millions of older adults worldwide are prescribed atypical antipsychotic drugs (quetiapine, risperidone, and olanzapine),” and that these drugs are “…frequently used to manage behavioral symptoms of dementia, which is not an approved indication…”

The research is based on a retrospective matched pair cohort study using information drawn from healthcare databases.

Method

From the databases, the researchers identified 215,543 Ontario residents who received a new oral antipsychotic prescription for an atypical neuroleptic (quetiapine, risperidone, or olanzapine) between June 2007 and December 2011. For the same time period they identified 1,726,930 residents who did not receive a new prescription for any of these products.

From these populations, they identified 97,777 neuroleptic drug recipients, and the same number of drug non-recipients, matched on eleven health status factors. They then checked the matching against 91 measured characteristics. The authors report that: “The 2 groups were well-balanced and showed no meaningful differences in the 91 measured baseline characteristics…” The percentages for the two groups on the 91 characteristics are set out in the report, and the groups are indeed extremely well matched.

Results

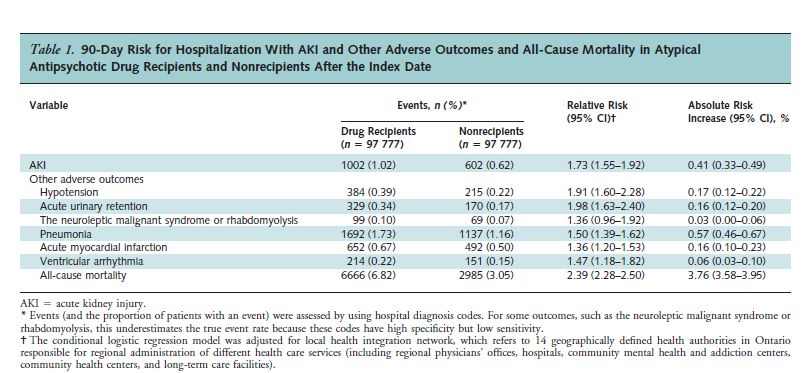

The study’s results are presented in Table 1.

As can be seen, the risk of acute kidney injury was 1.73 times greater for the drug recipients than for the non-recipients. Also, note that the risk for all-cause mortality was 2.39 times greater for the drug recipients.

There were 3681 “excess” deaths from all causes in the drug group during the 90-day period. That amounts to 3764 per 100,000 – almost 4%!

Because this was an observational study, as opposed to a randomized, controlled trial, it is not possible to say definitively that the drugs caused the excess kidney failures and deaths. However, the authors did take great pains to identify and eliminate confounding factors. For instance, they repeated the analysis for the 180 days preceding the index date, and found no difference in the incidence of AKI in the drug vs. non-drug groups prior to the administration of the neuroleptic drug. (relative risk 1.02).

The authors also point out that the excess mortality is consistent with the 17 randomized placebo-controlled trials on which the FDA’s 2005 black box warning was based. These trials showed a 1.6 to 1.7 times greater risk of death associated with neuroleptic use in older people with dementia. (Average follow-up period: 10 weeks).

It is also noteworthy that although high neuroleptic dose entailed a greater relative risk of kidney damage than a low dose (1.80 vs. 1.73), the difference was slight. In other words, even low doses were associated with acute kidney injury.

Discussion

On August 19, Medscape ran an article on this study. The author was Deborah Brauser. The article recounts the main findings of the study. Ms. Brauser also apparently interviewed Amit Garg, MD, the principal investigator. Here are some quotes from the article:

“‘I was actually surprised that this evidence was so robust. We did the study to determine what the association could be, and we clearly saw it,’ said Dr. Garg.”

“Because of this, Dr. Garg said he was surprised that so many patients were still receiving these prescriptions.

‘We looked at almost 100,000 adults in the province of Ontario who received these medications. This shows how commonly they’re used in just a single province, never mind worldwide,’ he said.

The researchers write that current evidence calls for a careful reevaluation of the prescribing of these medications in older adults.”

Also quoted in the Medscape article is Dilip V. Jeste, MD. Dr. Jeste is an eminent psychiatrist. He is a past president of both the APA and the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry. He was not associated with the present study, but in his interview with Ms. Brauser he referred to an earlier study that he and some colleagues published in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry in January 2013.

The objectives of that study were:

“To compare longer-term safety and effectiveness of the 4 most commonly used atypical antipsychotics (aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone) in 332 patients, aged > 40 years, having psychosis associated with schizophrenia, mood disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, or dementia, diagnosed using DSM-IV-TR criteria.”

And the results:

“Overall results suggested a high discontinuation rate (median duration 26 weeks prior to discontinuation), lack of significant improvement in psychopathology, and high cumulative incidence of metabolic syndrome (36.5% in 1 year) and of serious (23.7%) and nonserious (50.8%) adverse events for all atypical antipsychotics in the study.”

And the conclusions:

“Employing a study design that closely mimicked clinical practice, we found a lack of effectiveness and a high incidence of side effects with 4 commonly prescribed atypical antipsychotics across diagnostic groups in patients over age 40, with relatively few differences among the drugs. Caution in the use of these drugs is warranted in middle-aged and older patients.”

I found the last sentence quoted above puzzling. Given the findings, so clearly stated earlier, why not advocate cease and desist, rather than caution?

And in the Medscape interview, Dr. Jeste spoke very favorably of the current study:

“‘I think this is a really good study…'”

“‘It had a large sample size, and it was interesting how they selected people. They chose only those who were starting on the atypicals, which is appropriate. They also followed them for 90 days and did their best to have a similar control group.'”

But, again, puzzling:

“‘The bottom line is not that people should stop using these medications in older people. However, they should be more cautious, especially in patients with low blood pressure or evidence of kidney injury in the past.'”

There is this enormous reluctance among psychiatrists, even those who clearly have begun to see the light, to take a clear, unambiguous stand against harmful interventions. So often, they settle for the old face-saving caveat – “use caution.” But how can one use caution in prescribing a drug for an age group in which it has been shown to lack effectiveness and has a very high incidence of serious adverse effects? Surely the cautious approach would be not to use these drugs at all, especially since it’s virtually impossible to predict which individuals will suffer AKI or other adverse outcomes, including death.

Even Dr. Garg, principal investigator in the present study, backed off a cease and desist recommendation.

“The current available evidence calls for a careful reevaluation of prescribing atypical antipsychotic drugs in older adults, especially for the unapproved indication of managing behavioral symptoms of dementia…The drugs should be used only after other approaches have been exhausted; when prescribed, patients must be warned about potential adverse effects. Proactive clinical monitoring shortly after initiation seems reasonable (for example, serum creatinine and blood pressure measurement, and if readily available, a bladder scan to detect urinary retention). When patients present with AKI, atypical antipsychotic drugs should be considered a potential cause and be promptly discontinued if feasible.”

And in his interview with Ms. Brauser:

“‘We wanted to raise awareness around this issue and recommend that physicians should be cautious around the use of these medications in the elderly,’…”

And

“‘However, if a patient is on this medication and the physician is monitoring it very carefully, we don’t want to be alarmists. But it’s healthy to have these types of conversations.'”

Also, Incidentally

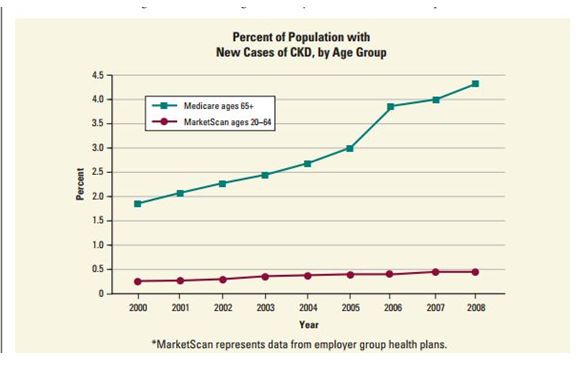

The incidence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) is increasing among people 65 and over.

Here’s a graph from the National Kidney and Urological Diseases Information Clearinghouse:

I’m not suggesting that all of this increase is due to neuroleptics. However, AKI often progresses to chronic kidney disease, and given the widespread prescribing of these products, it is reasonable to infer that the neuroleptics are a significant contributor.

Here’s a quote from a 2009 editorial of the Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, The Nexus of Acute Kidney Injury, Chronic Kidney Disease, and World Kidney Day 2009, authors Mark Okusa, MD, et al.

“Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a devastating disease that affects patients throughout the world and is associated with high morbidity and mortality. It has been traditionally thought that patients who do survive recover renal function; however, recent population-based evidence strongly suggests that this may not be the case in many instances. New data suggest that a strikingly large percentage of patients who have AKI require permanent renal replacement therapy or do not fully recover renal function, and that this population has an important and growing impact on the global epidemiology of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage renal disease (ESRD).”

And a Final Note

In 2009, Gwen Olsen published her book Confessions of an Rx Drug Pusher. In one of the chapters, she described how she systematically, and successfully, targeted nursing homes as markets for neuroleptic drugs.

There is a very poignant passage in which she describes, with considerable remorse and misgivings, how a particular resident – an elderly lady, exuberant and at times feisty – was reduced to a docile, inactive shell of her former self through a neuroleptic prescription.

Ultimately it’s a business. And it won’t stop until the cost of doing that business exceeds the profits. The findings of Dr. Garg and Dr. Jeste are helpful, of course They provide clear and unassailable evidence for what we already know: that in elderly populations, these drugs are being used as chemical straitjackets to “manage” agitation and aggression, and are killing people in the process.

But it is unlikely that polite calls for “caution” will stem the tide.

* * * * *

This article first appeared on Philip Hickey’s website,

Behaviorism and Mental Health

Cease and desist? Wheres the entrepenuer in you Dr Hickey? Surely this is a reason to add other medications to the list to counter this effect. Hands up any big pharma companies with a solution.

Report comment

boans,

Of course! Silly me.

Report comment

Medical marijuana is a humane alternative to neuroleptics to treat abuse averse elderly nursing home residents

Report comment

I can’t quite figure out why the medical profession thinks the drugs know how old the person is. The neuroleptics were known to be torture drugs back in the 1970’s, when the Russian dissidents came over describing them AS torture drugs. The UN has stated “forced psychiatric treatment is torture.” What’s wrong with our medical community? The neuroleptics are good for lazy and unethical doctors and drug companies, and bad for patients of ALL ages, period.

Report comment

Someone Else,

Yes. They damage people of all ages.

Report comment

Thank you once again for this well-conceived and clearly written article. Yet another weapon in our arsenal to fight against these abusive drugs.

Now we have to use these weapons by figuring out how to bring facts like these to the attention of the public.

Report comment

Ted,

Yes. They’ve lost the intellectual and moral debate, but they’re still ahead in PR and spin.

Report comment

A veritable eugenic euthanasia wet dream of the Rockefeller, Carnegie, Harriman,Turner.Gates,etc come true in the guise of medical care . Should we not call it Mengele Care ?

Report comment

“‘The bottom line is not that people should stop using these medications in older people. However, they should be more cautious, especially in patients with low blood pressure or evidence of kidney injury in the past.’”

WTF? How are you cautious when you’re drugs cause metabolic syndrome, kidney disease and early death? If teh group matched so well then it’s clear there are no predictive factors which patients are going to develop these problems. If the drugs also have low efficacy (however you measure that) then you should stop prescribing them period.

Report comment

Good point.

What’s next?…

“be cautious when prescribing to patients with a history of early death?”

Duane

“If you don’t know where you are going any road can take you there”

― Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland

Report comment

Discover and Recover,

Yes. Or: be cautious when prescribing to human beings!

Report comment

B,

I couldn’t agree more!

Report comment

My psychiatrist never ordered any lab work or had me get checked for certain problems the neuroleptics could cause. He always seemed stupefied with my complex physical problems when it was the drugs causing them. His prescribed and prescribed without accepting any medical responsibility. My wake up call was developing Seroquel Induced Acute Pancreatitis and almost dying.

Report comment

aria,

What a nightmare! And yet not that uncommon. There is truly no human problem that psychiatry won’t make ten times worse.

Report comment

More fuel for the argument, Phil! Thank you! tw

I entered the tween stage, that is, 55-65, when we get to be halfway elderly and occasionally can take advantage of “senior discounts,” with a bang. I decided to use a slogan to describe my age: “55 and Alive!” Some seven months later, I experienced acute kidney failure. I am lucky to be alive today.

The psychiatric profession appears to be desperate to deceive patients and keep them in the dark about consequences, even if it means hiding important information regarding medical conditions from patients so that they will continue to comply. For years, my kidneys were running low, and I wasn’t told. When I arrived at an ER and I went into full code last August, a nurse blurted out to me that I was in kidney failure. I believe they hoped I wouldn’t recall this blunder. However, for whatever reason, I remember well. My electrolytes were so off at that point that it didn’t even register in my mind that I was near death. I was merely curious as to what would occur next. For over a month I’d been feeling like I was on a moving ship, or was the world just tilting back and forth the whole time?

I was up on the floor and I asked flat out what had happened. I repeated what I’d heard and they said, accusingly, “Who told you that?” as if it were a lie or my imagination. I was in the hospital 11 days. Every day, each morning, i was offered Abilify and I refused it. The doctor in charge finally told me if I didn’t take Zyrexa, he wouldn’t allow me to leave the hospital even if I was medically stable enough to leave. He’d pushed many antipsychotics on me, including Haldol, and i’d refused all of them. Their main goal, as far as I know, was to transfer me to a psych ward where I’d be started on the deconate, and court ordered to stay on it. I’m sure, had I refused, I would have been transferred to a state facility.

I told the doctor that I didn’t think Zyprexa was an appropriate medication for a person with anorexia nervosa. It had already been proven to be unhelpful for anorexia, and it’s not approved, either, as off-label use. I’d taken it before with disastrous results.

I learned that I’d gone into renal failure because the the day I went home free the discharge doc accidentally gave me papers I shouldn’t have had access to. I was alone late on Friday night when I found out I’d nearly died, and they never bothered to tell me.

I have a new slogan, “56 and Free.” I am lucky to be alive. My kidneys are roughly at 1/3 functioning. I know now that they were desperate to keep me from writing or speaking out about what happened.

Sorry, docs. I am a writer and my weapon is my pen. They were desperate to stop me even if they had to tell huge lies. You can stab yourself with a pen. But why do that, when you can put it to far more powerful use?

I love ya’ll, Julie Greene and her little dog, Puzzle

Report comment

Julie,

Thanks for coming in. You write:

“The psychiatric profession appears to be desperate to deceive patients and keep them in the dark about consequences, even if it means hiding important information regarding medical conditions from patients so that they will continue to comply.”

That is so true, and it betrays psychiatry’s condescending arrogance towards its clients. Real doctors go to great pains to explain adverse effects. But psychiatrists often don’t, or, if they do, it’s glossed over as inconsequential. And, of course, their good old stand-by: the benefits outweigh the risks!

Report comment

“Real doctors go to great pains to explain adverse effects.” This is true if you consider that many regular doctors are not “real doctors.”

Many regular doctors are caught up in the idea that medications are largely “risk-free” or, as you say, have benefits that outweigh the risks. There is a lot of pressure put on people to take drugs such as statins for life. No drug is risk free, and many drugs are extremely destructive long term. Doctors, as a group, are fuelling the mindless pill-popping.

Psychiatrist are more egregious in their use of drugs partly because they are not dealing with real disease and partly because the people diagnosed are social nuisances (to someone). This latter reason creates a situation where, for those in control, the benefits always outweigh the risks, they being in a position to reap the benefits while the “disordered person” takes the risk.

Report comment

Honestly, I have not met a doctor who actually thinks a good deal about your symptoms and diagnosis and even has a conversation with you about the side effects in like years. It’s mostly 5-10 minutes and a prescription. No mention of side effects, sometimes they don’t even tell you what the drug is or what it is supposed to do. It’s like “sore throat? neck pain? broken leg? take this twice a day, next please”.

Report comment