I am an artist, musician, and writer. I am also a former inpatient and survivor of twenty years of hospitalization at Creedmoor Psychiatric Center in Queens Village, NY.

Though now an outpatient, I am still firmly connected to that hospital’s Living Museum, a world-renowned artist’s sanctuary/rehabilitation program that was the subject of an HBO documentary directed by Academy Award winner Jessica Yu in 1999. As a result of my exposure there, my work has been seen in galleries from Atlanta to Istanbul and has been acquired by art collectors from Oyster Bay to Austria.

Writing my memoirs behind the walls of Creedmoor, I have done plenty of soul searching and research, but I don’t really know what it is that makes me different from the multitudes of people who have spent time in hospitals after a devastating psychosis – or those currently inside, some with little or no hope or understanding of their condition. It seems like a miracle that I have my mind back and that it functions properly and prodigiously, even if it did take twenty years before a judge decided I was ready to leave. Six years after my release, it still amazes me that I survived a situation of complete uncertainty and still stayed sane, blessed with a faint but persistent glimmer of hope: hope that I would get better, stay well, and someday see the outside world again.

Though I have achieved some success as an artist, skirting just outside the “Outsider” arena, I often felt like a hothouse flower cultivated under extreme protection and restriction. I was allowed to create and grow at Creedmoor’s Living Museum but was not seen as an artist-at-large by the average viewer out in society. This created an unhealthy mix of both appreciation for my captors and hatred, similar to a slave’s life on the plantation. As a result, I found myself subconsciously acting out – having sex with staff, painting unflattering portraits of hospital administrators, and writing, recording and releasing scathing songs about these same bureaucrats. In a short time I got my wish and was flying above the radar and eventually buried under the jail, labeled “high profile” with damning progress notes and re-diagnoses basically throwing away the key on me.

These activities, however provocative, tuned me in to the fact that regardless of the pressures I felt, I was and will always be an artist. So I suppose it is the arts that truly helped me survive. But aside from the healing properties of the arts, for those 20 years how did psychiatry treat my body? Largely with ignorance.

The New York State-employed psychiatrists that I encountered focused almost exclusively on treating my diseased mind and had no concept or interest in the body. As with the large majority of my peers, over the years I struggled with bad teeth and weight gain – these and other physical issues were at best delegated to the ward and hospital physicians. State hospital care is infamously subpar, with dentists yanking teeth instead of saving them, and other triage techniques.

Diagnosed with schizophrenia, I have been on Haldol injections since 1998. I haven’t developed tardive dyskinesia, an irreversible nervous system disorder characterized by permanent involuntary facial tics and body movements, which is a huge and horrible component of the Haldol experience for most of its users. Haldol is one of the oldest anti-psychotics still in use besides Thorazine, and even then they are used sparingly. There are plenty of drug company representatives who woo psychiatrists with clever but cheap trinkets and tchotchkes like T-shirts, paperweights and even paid dinners for promises to administer (read: experiment with) their latest, greatest wonder drug. Until my tongue starts doing donuts in my mouth I’ll stick with old faithful, thank you.

A major drawback to my medication regimen is the monthly pain and profound swelling at the site of the shot, and fever for 48 hours after I receive it. Though I complained of the seeming allergic reactions every month, no one ever discussed the possibility of these side effects with me or attempted to reduce them; some doctors unfamiliar with them even believed I was malingering. After several years and numerous complaints I was given the advice to self-administer warm soaks, then icing; finally I was offered a PRN of Tylenol to keep me quiet.

There are other medication reactions and side effects in the treatment milieu which vary from annoying but relatively minor afflictions such as blurred vision, dry mouth, stiffness, increased thirst and appetite, and constipation, to severe nerve damage, organ failure and eventually death. The usual cure-all is to be prescribed more drugs, such as Cogentin, which is a muscle relaxer that comes with its own side effects, but they haven’t worked the kinks out of that yet.

It must be said that most of these negative reactions are related to the older medications that were engineered many decades ago – medications that tranquilized the patient, subduing the delusions and hallucinations yet spreading out into other parts of the brain and nervous system, causing havoc and mayhem on areas that didn’t need to be disturbed by the drug. In recent years, there have been newer psychotropic drugs that allegedly target specific areas of the brain, arresting the damage with reduced side effects and bringing hope to sufferers who were previously untouched by earlier drugs or therapy. The downside of this is the discovery that after five or so years of constant use of some of these “wonder drugs,” and without the proper education of the patient about these medications and their relationship to diet, there is a likelihood of developing additional maladies such as diabetes and, strangely enough, obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Because State psychiatrists are overworked and understaffed, they will often inadvertently neglect the patient. The psychiatrists here in Creedmoor and psychiatry in general do not address the body. Instead of sitting with the patient for the documented 15-30 minutes, they rely on the observations of the rest of the treatment team, never discussing dental or dietary health or especially sexuality unless there is a transgression. There was never any counseling on how my medication would affect my sex drive, or the various potential dysfunctions that accompany the drugs.

Two of the most prevalent earmarks of being a mental patient are having bad teeth and obesity, not to mention smoking cigarettes, patients being the biggest consumers of the product because they work as tranquilizers. My teeth have always been a weak point for me, being crooked, spaced, and with a slight patina; I haven’t had the opportunity to have them appropriately fixed as I would have liked. The dentists here at Creedmoor seem to get a bonus for each tooth pulled, for all the aggressive yanking they propose whenever they look into a patient’s mouth. Knowing how bad the mouths are in these hospitals, I don’t envy the dentists one bit.

While inside I took to a twice-daily regimen of attentive brushing and flossing, the latter being done on the sly because floss is classified as contraband and thus not allowed. It is sad that something so essential to good dental health is suspect and banned, probably to prevent someone from hanging themselves or someone else from their molars. My girlfriend was even more vigilant than I am about dental hygiene, due to a bout of gum disease brought on by her meds a while back, and she would frequently slip me a box of floss when I was running low. So, to put it plainly, in the fight against poor dentistry and drug-induced decay I am doing the best I can.

Once a bustling community, almost a mini-town, Creedmoor in the middle of the twentieth century had upwards of six thousand inpatients and a healthy employee workforce. The ward staff roster was so formidable that they adopted the name Mahatas for themselves, an acronym for Mental Health Treatment Aids. They would oversee and often help the patients who tended farms and gardens on the grounds, making the hospital a self-sufficient asylum in the truest sense of the word – a place of shelter and protection from the harsh reality of life found outside the gates. The gardens allowed residents to engage in the beneficial and healing experiences of physical activity, working with living plants, getting one’s hands in the soil and getting plenty of fresh air and sunshine.

With the introduction of medication and later de-institutionalization, the farms and gardens were abandoned, the census shrank, and the Mahatas grew bored, bitter and paranoid, recognizing their imminent obsolescence and reduced role from caregiver to that of toy cop and turnkey.

The old asylum ideology has gone by the wayside in the modern age, and formerly homegrown foods are now warehoused, pre-fab processed meals akin to TV dinners and airline fare. Concurrent with the great hygiene neglect there is extremely poor nutrition in this community. Diet is ignored in psychiatry. Ketchup was deemed a vegetable by the government, and hospital nutritionists followed suit. There was never any consultation with me about diet or my prescribed medication’s effect on weight gain. I have come to understand that this is commonplace. The doctors assume the patients are too stupid to understand the importance of good nutrition, and they usually don’t go out of their way to educate. It should be noted that a restricted patient begins their climb up the Privilege Levels ladder with doctor’s orders to leave the ward and spend half an hour at the snack machines. It is no surprise to see many patients having Pepsi for breakfast, a Honey Bun for lunch, and Doritos for dinner.

This is not a patient’s complaint of inadequate treatment and bad hospital food, but a heartfelt plea to stem the retrogression from high-quality produce harvested from the asylum farm that the patient could eat as much of as they wanted (like it used to be at Creedmoor), to the current model. The move toward parsimoniously-portioned pre-packaged meals offset by vending machine junk food is a blatant health hazard.

Throughout the last ten years of my stay I fell into a steep depression, and with the introduction of an appetite-increasing neuroleptic and no consistent exercise, I developed significant weight gain. It’s easy to see how and why, considering a psychiatric inpatient leads a sedentary life in a place where even your supposed role models the Mahatas sit around lazily, barking orders from a comfy chair behind the nurse’s station. The stigma and discrimination of the “mentally ill” seem to begin inside the hospital, starting with the psychiatrists and trickling all the way down to the janitorial staff. On the wrong side of that great dividing line of patient and staff, one can read clearly the disdain in the faces, hear the condescension and feel the standoffishness. We are othered by the very people pledged to help, before we even hit the streets.

As soon as I was discharged and started exercising regularly and eating right, I brought my weight down by 30 pounds. I am now mentally and physically healthy and happy, fortunate to be a survivor of my treatment.

While the wheels of “progress” turn slowly in mental health, I hope that along with ongoing advocacy there will be a focus on responsible health counseling and supporting people in smoking cessation and healthier eating and living. We need to educate and implement alternatives to the common cliché of the coffee, cigarettes and junk food addicted psych patient if we are to outlive these and other negative stereotypes, in addition to living a healthy and rewarding life.

“The stigma and discrimination of the ‘mentally ill’ seem to begin inside the hospital, starting with the psychiatrists and trickling all the way down to the janitorial staff. On the wrong side of that great dividing line of patient and staff, one can read clearly the disdain in the faces, hear the condescension and feel the standoffishness. We are othered by the very people pledged to help, before we even hit the streets.”

So true, I’ve never dealt with disrespect from anyone really, other than doctors, psychiatrists, and pastors who wanted to cover up easily recognized iatrogenesis and medical evidence of child abuse by creating psychosis in me via what’s known as anticholinergic toxidrome, but they called the known drug interaction induced illness, “bipolar.” I found psychiatrists to be the most disrespectful, and unethical, people in the world.

I, too, am an artist. It does seem the psychiatrists like to poison the creators. Personally, I believe those who create, or work to turn ugliness into beauty, are more beneficial to humanity, than those who create “mental illnesses” in others with drugs, for profit.

Report comment

The cleaners and kitchen staff were pretty good in the Ariel Castro Memorial. And at first I thought that being treated like a dog was kind of rude. It was only when it was explained to me that this is a valid scientific test for Clinical Lycanthropy that I got why. I might have been a werewolf lol.

Seen a lot of disrespect in my time, but never a place where it was a major part of the business plan.

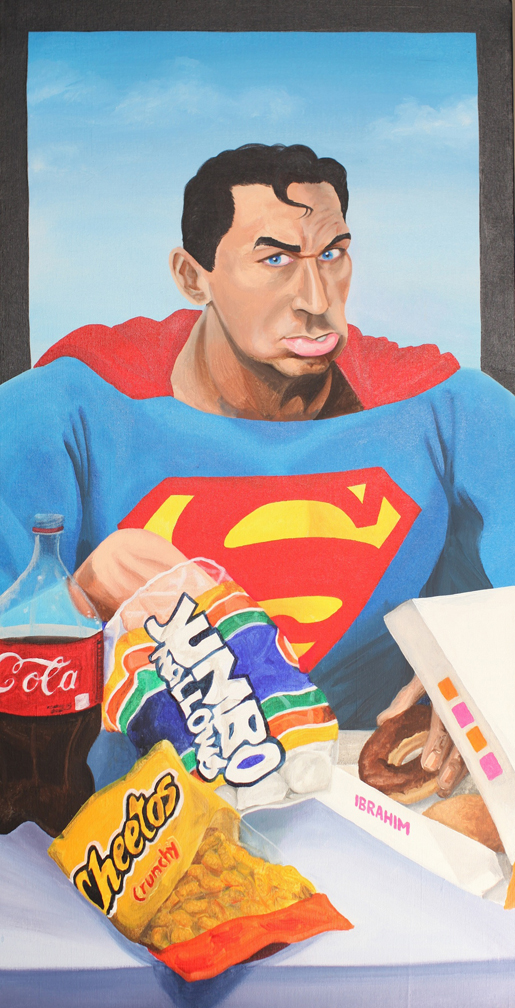

I’m fascinated by your art Issa. The ‘super hero’ combined with various cultural icons is …. thought provoking.

Regards

Boans

Report comment

Dear Boans,

LOL on the werewolf jibe! Thank goodness you weren’t on the receiving end of what many others believe is business as usual.

Thanks for the kind words about the artwork, and forgive my late reply.

Cheers!

Issa

Report comment

Thank you for this powerful essay.

Report comment

Dear TIP,

Thank you for the kind words and for resonating, and forgive me for the late reply.

Cheers,

Issa

Report comment

How do you feel about the diagnosis of “schizophrenia” as an explanation for the circumstances which led your becoming an inmate at Creedmore?

Report comment

That is a good question Oldhead and one I was thinking while reading this piece too.

Let me comment a little on this Issa – it’s an excellent article. I an an art lover and really admire your work. I think the inattention paid to your physical / dietary wellbeing is criminal. I’m glad that you are doing better and wish you had been able to get humane understanding and support much earlier rather than having to live apart from mainstream society for so long. You could have been much freer much sooner if you were approached as a person in distress needing understanding, rather than an object with a diseased mind needing to be drugged.

But when you say the psychiatrists were “treating your diseased mind” – to me this suggests that part of you believed the psychiatrists who said you “had a mental illness” named “schizophrenia.” Let me say that I think extreme states of mind, including delusions and hallucinations are totally really and very dificult – I’ve experienced these too. But to say that these experiences are evidence of something abnormal or “ill” is a mistake, to me.

I wonder if you’ve read the books and papers criticizing the validity of so-called schizophrenia by Richard Bentall (Madness Explained), Mary Boyle (Schizophrenia, A Scientific Delusion), Mancuso/Sarbin (Schizophrenia, Medical Diagnosis or Moral Verdict), and the writing attacking the illness viewpoint in general by Thomas Szasz and R.D. Laing. Jeffrey Poland would be another good writer in this line.

The point is that there is no clear line where normality becomes disease, and that to have delusions and hallucinations does not mean that one has a disease called schizophrenia; in fact, there is no such illness which is separable from other extreme states of mind or from normality. I used to believe it was valid myself, but I don’t anymore, because once you read between the lines and read the authors I cited, it just doesn’t make sense.

Anyway, this bone of contention is really immaterial for your particular case. What matters is that you got out of the situation you were in, got better, and are now emotionally and physically in a much better place. But I think that with people who are now caught in the grip of psychiatry’s mental illness lie, it’s important to challenge the lie that schizophrenia exists as a valid separable mental illness.

Report comment

That was so beautifully well said that I’m still smiling, and will be for a very long time.

After thirty-five years involved in the mental health world, poly drugged the entire time, I have literally had to de-brainwash/de-program what psychiatry had put there. All I knew how to do was group every emotion I had and squeeze it into a mental diagnosis, because that’s all they had been doing for decades. Now that I’m off the drugs, I’m not mentally ill, I’m not mentally ill at all. In fact, I haven’t felt this mentally well in a very, very long time.

Your comment was a joy to read. Thank you. I couldn’t have said it better myself.

Report comment

Wow, what a story. Boy, I flashed right back to when I was in the Kalamazoo State Hospital remembering how every attendant, mostly women, used to sit at the nurses station, up higher than everyone else, and either just turn their heads when they saw you approaching or you were greeted with icy, cold stares. Ooohhh, it gives me chills.

Mr. Issa Ibrahim, you just keep doing what your doing. Your very inspirational to me.

Report comment

Dear Sanderella,

Thank you for resonating and continued blessings on your journey to wellness.

I was truly taken by your mentioning “de-brainwashing and “de-programming”…wow! I too went through that, after 20 years of the wash rinse and dry, and it’s taken years to re-think and re-orient my brain to not think I am everything they pushed on me all those years. What you said was a validation and I appreciate it.

Cheers,

Issa

Report comment