On Tuesday, March 8th, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) entered into a settlement agreement in Amarin Pharma v. U.S. Food & Drug Administration, allowing Amarin to promote Vascepa, a prescription drug that consists of pure “EPA” (eicosapentaenoic acid), an omega-3 fatty acid, for off-label use to treat patients with persistently high triglycerides, so long as its promotion is truthful and non-misleading. This followed a trial court decision last August that the Food, Drug and Cosmetics Act does not prohibit truthful, non-misleading off-label promotion because to do so would be an unconstitutional restraint on commercial free speech. This, in turn, was based on the 2012 decision of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, in United State v. Caronia, reversing a criminal conviction on this basis.

In its Opposition to Amarin’s Motion for Preliminary Injunction, the FDA argued that Caronia was limited to its facts, and that Caronia did not prohibit use of speech to prove intent, propositions with which the trial court in Amarin disagreed. Similarly, with respect to yesterday’s settlement, the FDA said it is “specific to this particular case and situation,” and did not mark a legal precedent. This is pretty much beside the point because the FDA has decided to cave in the Amarin case and, as the trial court noted in Amarin, the FDA never challenged the Caronia decision, either through asking for rehearing or by asking the Supreme Court to reverse the Second Circuit. Thus, it is the law in the Second Circuit (New York, Connecticut & Vermont) that the FDA cannot criminally prosecute someone for the truthful, non-misleading off-label promotion of drugs. I am not going to get more into the weeds on all the legal analysis of the Amarin case, but the FDA Law Blog has a pretty good analysis here.

Amarin also asked for a ruling that truthful, non-misleading off-label promotion of drugs cannot form the basis of a False Claims Act case for causing prescriptions to be written for drugs that are not for a medically accepted indication and therefore not covered under federal healthcare programs. Under Medicaid, Medicare and TriCare, the government is generally only allowed to pay for prescriptions that are for FDA approved uses or uses supported by at least one of specifically identified drug references called “compendia.” Approved uses and uses supported by at least one compendia are defined by statute as “medically accepted indications.” “Off-label” means for a use not approved by the FDA. Thus, off-label prescriptions to federal healthcare recipients is a false claim unless it has “support” in one of the compendia. The judge declined to rule on the issue one way or the other because it did not find a ripe controversy since the FDA had not threatened such a lawsuit.

In light of the settlement I think it is fair to ask where things stand with the FDA’s enforcement of its ban against off-label promotion and Department of Justice prosecutions of drug companies for off-label promotion leading to false claims. I think the ban against off-label promotion is dead for all practical purposes. The FDA could try and get a different ruling in another circuit and, if successful, ask the Supreme Court to rule, but since it didn’t ask the Supreme Court to take the case in Caronia, it doesn’t seem likely that it has any intention of trying to overturn Caronia. This will give the drug companies free rein for off-label promotion. Of course, anything that is false or misleading is still grounds for charges, but that is a far harder case to make.

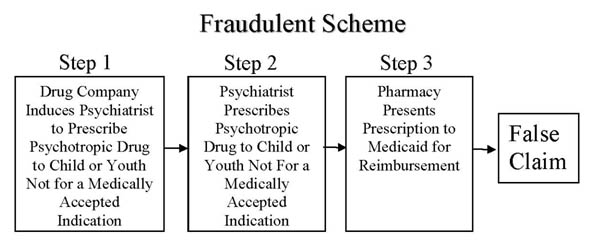

As to the False Claims Act, it is fair to ask if the era of big settlements is over. By 2012, the Government racked up over $30 Billion in criminal and civil penalties for drug company promotions leading to prescriptions to federal health care participants that were not for a medically accepted indication. This was at Step 1 of the following graphic.

While the court in Amarin declined to rule on whether there can be False Claims Act liability for truthful, non-misleading statements causing false claims, it seems highly likely that the Free Speech Argument will be brought up in such False Claims Act cases. Maybe the drug companies will continue to agree to these large settlements, but it seems likely there will be challenges based on the Free Speech argument. Is the government willing to litigate the issue? We will see.

PsychRights’ Medicaid Fraud Initiative Against Psychiatric Drugging of Children & Youth is based on Steps 2 and 3 of the above illustrated Fraudulent Scheme. In August of 2013, the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals issued its Decision in ex rel. Watson v. King-Vassel, that doctors cause false claims by writing prescriptions to Medicaid recipients that are not for a medically accepted indication and this is unaffected by the Caronia and Amarin decisions. The government has decided not to pursue claims at Steps 2 and 3 of the Fraudulent Scheme and while doing so would presumably pay huge dividends in reduced prescription costs and dramatically decrease drug caused harms, it seems unlikely it will change its policy. I continue to believe that private citizens pursuing these cases has a good chance of dramatically reducing the psychiatric drugging of poor children on Medicaid. The same is true of psychiatrically drugging the elderly in nursing homes to suppress them.

I also think it is worthwhile to look at a couple of big picture trends that seem evident. First, the Caronia decision is illustrative of the federal courts having swung far back to protecting business interests over the safety, health and welfare of people. It reminds me of the late 1800s and early 1900s when the Supreme Court struck down all manner of laws to protect people such as children from sweatshops, miners from unduly hazardous working conditions, and regulating hours and wages, as violations of the right of contract under the 14th Amendment’s incorporation of the Due Process Clause. This was exemplified by the 1905 United States Opinion in Lochner v. New York, in which the Supreme Court struck down a law limiting bakeries from having people work more than 60 hours a week or 10 hours a day.

Second, the Amarin Settlement seems to be an abandonment by the federal government of protecting the public from off-label prescriptions. This might seem harsh in light of the government being boxed in by the Caronia decision, but the billion dollar drug company settlements were never more than show prosecutions. These settlement were just the cost of doing business for the drug companies, while they continue rake in huge profits from the continued off-label prescribing of drugs that do not diminish after the settlements. This is reinforced by the government’s policy of not enforcing the restriction to medically accepted indications.

Since there are no real medical diagnoses in psychiatry, one could easily argue that the use of psychiatric drugs has always been off-label, in every case, ab initio…

Report comment

This Zyprexa also works “great” off label for anxiety and insomnia, till it robs your ability to feel joy from anything in life (anhedoinia) so you try and stop taking it, don’t refill it and find yourself having wicked nausea, insomnia 1000x worse, pacing back and forth in your home having anxiety attacks and puking on the back steps for weeks. The first time you goto the ER after they see you the nurse says “the doctor can write you more Zyprexa if we ask him nicely” and you leave the place with more of the poison that brought you there in the first place to avoid getting locked up in psych.

Then after failing to taper off it completely and use up the 10 pills you go back to that ER again complaining of nausea vomiting anxiety attacks and demand help and answers in medical terms to what that crap did to your body causing nausea vomiting you do get sent to psych, you never see a gastroenterologist and they label what that Zyprexa poison did to you “schizoaffective” disorder and try to feed you effing Geodon. When its all over and you are mislabeled and mistreated you get a bill for $25,000 !! and are still going to be sick for months and need ativan for the continuing withdrawals.

What’s with this case, is it now legal to push Zyprexa off label ?

Report comment

The way things are looking, especially in the 2nd Circuit, it seems that “truthful, non-misleading” off-label promotion is allowed. While we know the promotion will be false and misleading, the government having to prove that is a whole other level of difficulty. And, of course, the drug companies will point to their bogus studies to show that they are being truthful.

Report comment

I wonder if the drug companies will fight with each other claiming their competitors promotion is false and misleading.

Report comment

Is this an example of off-label prescribing?

Practice Patterns for ADHD and Other Disorders Collide

February 09, 2016 | ADHD, Bipolar Disorder, Career, Dementia, Psychopharmacology

By Gabriel Kaplan, MD

http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/adhd/practice-patterns-adhd-and-other-disorders-collide?GUID=&rememberme=1&ts=16032016#sthash.xynPNovr.dpuf

Report comment

Yes

Report comment

Read about this study reported in the January issue of “JAMA Internal Medicine” and thought it was ironic to have been published in the midst of the FDA settlement with Amarin. Eguale et al. systematically looked at the association between off-label use of prescription drugs and adverse drug events (ADEs). They found a higher rate for off-label use that was not supported by strong scientific evidence. Here’s a link to the abstract: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=2467782

Here’s a link to a Medscape article on the study: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/854200

“[P]hysicians and physician organizations should recognize the enormity of the problem and be active participants in the promotion of cautious prescribing of drugs for off-label uses lacking strong scientific evidence.”

Referring to the Amarin court decision, Good and Gellad commented on the Eguale et al. study and said: “In light of these concerns, the study of off-label drug use and adverse drug events by Eguale and colleagues … is particularly timely.” Here’s a link to their commentary: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=2467779

Report comment