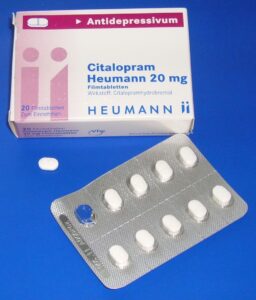

Researchers, Jon Jureidini, Jay Amsterdam and Leemon McHenry, have taken a closer look at the data from a randomized control trial of citalopram (Celexa) that was ghostwritten and then used by the manufacturers to support claims of the drug’s efficacy and safety in the treatment of child and adolescent depression. Their analysis used 750 recently-released court documents from a lawsuit against Forest Labs concerning the marketing and sales practices involved in the off-label promotion of Celexa. Drs. Jon Jureidini and Jay Amsterdam were expert witnesses in the case. The article is published, open-access, in the International Journal of Risk & Safety in Medicine.

To get the background on this story, we connected with Dr. Leemon McHenry, an investigator in this study and a lecturer in philosophy at California State University, Northridge.

Can you discuss how you first came across this citalopram study and what caused you to look into the claims in more detail?

I am a research consultant for the law firm of Baum, Hedlund, Aristei & Goldman in Los Angeles, California that takes up cases against pharmaceutical companies. This law firm is committed to exposing the misdeeds of drug companies by making sure that the confidential documents produced in the course of litigation are ultimately released to the public and independent researchers.

Following the revelations of Study 329, in which Glaxo Smith Kline (GSK) misreported the efficacy and safety of paroxetine (Paxil) for adolescent depression, we began to look at all of the studies that came out during this push by pharmaceutical companies to get psychiatric drugs approved for pediatric use. So, what your readers may already know in this case is that paroxetine did not get licensed, and so all of the prescriptions of this drug to adolescents were “off-label.” That is legal for doctors to do but it is illegal for pharmaceutical companies to promote drugs for off-label uses. Forest’s citalopram was in the same situation.

Citalopram study CIT18 was one study that was used to get approval for escitalopram (Lexapro) use in adolescent depression, so that made this study particularly important. Ultimately, the FDA granted the license based on two studies that were supposed to be positive, but it turns out that this study CIT 18 that we wrote about was, in fact, negative, and the other one was questionably positive.

This study was used to justify the FDA’s approval of citalopram for the treatment of depression in adolescents. In your estimation, should the FDA have made this approval given the existing evidence?

I don’t think that the FDA was fully aware of the extent to which this trial had been misrepresented.

This is the kind of thing that comes up in litigation where lawyers file suit, and the companies are obligated to make these document productions available as evidence. So you are going through millions of pages of documents and, you know, the FDA just doesn’t have the manpower to do anything like that. The FDA pretty much has to trust that the companies are giving them reliable data when in fact they are not. Therein lies the problem.

Only a relatively small number of the documents, in this case, were made available, and we posted these on the University of California San Francisco website, Drug Industry Document Archive, (DIDA). Those documents provided the opportunity to critique study CIT 18 and write this paper.

What is “medical ghostwriting” and how does it affect research on psychiatric drugs?

I think ghostwriting is the vehicle for misrepresenting the actual study results. There are hundreds of these medical communication companies proliferating all around the world, but in particular in the United States, England, and Australia; they are basically public relations companies engaged in marketing. These are the businesses that employ the medical ghostwriters who produce articles for the publication plans of pharmaceutical companies. This includes all of the articles they plan to publish based on their clinical trials, and it is the ghost writers at these medical communication companies who do all of this work writing up articles based on the data summaries provided by the statisticians.

Then what happens is that articles go through a lot of drafts, maybe 10-15 drafts, that get passed around between the statisticians and the marketing people at the companies and then, after most of this has already been written, they go looking for the so-called “author” of the paper. What often happens is that the academic physician they identify, the so-called “author,” doesn’t even see the article until it has already been drafted and revised by all of these people internally at the companies. This is just a dirty little secret of how marketing in medicine works. The ghostwriters are these individuals who are completely invisible in this process of promotion.

What is the potential harm done in this case?

Well, first of all, what we want is a system that is transparent and honest – and that’s what we don’t have because all of this ghostwriting is meant to be kept secret from the public. Even prescribing doctors don’t know that this is going on. If you tell prescribing doctors that the medical literature that they rely on is ghost written by agents of the pharmaceutical companies, most won’t have the slightest idea what you are talking about. They might look at you as if you’re crazy.

So, first of all, there is a question about scientific honesty, transparency and academic integrity. What we have is a situation where these academic physicians at universities work as “key opinion leaders” for the pharmaceutical companies. They will have as much as seven hundred, eight hundred, or even nine-hundred publications on their curricula vitae. They are supposed to be models for professors to emulate at their universities, but this is essentially academic plagiarism. They might not have done any of this writing at all. They might not have even checked the data, and they certainly have no idea whether the data that is being reported in these studies is accurate or not.

So that’s one problem. Now the other problem is the potential harm that comes from this situation and ghostwriting has been documented as a vehicle for misrepresenting results when there are serious safety issues. The most famous case, of course, is Vioxx. That drug contributed to all kinds of deaths and serious harm to people and then it was discovered that the one key article on this drug that was distributed to prescribing physicians all over the world was ghost written. The lead author on that paper said afterward that he didn’t write the paper and that he just trusted the data he was given.

The same thing has been going on with the SSRIs and, in particular, when you’re dealing with a very vulnerable patient population such as children and adolescents, you have a real problem concerning trust in the medical literature. This is not only an issue for prescribing doctors, but it is also a problem for people who set health care policy in government. Also, these articles are very often used in court when the pharmaceutical companies try to defend themselves. So, not only do you have fraud on the medical community but you also have potential fraud in the courts.

So, when you talk about harm, you can point to cases like Merck’s Vioxx or GSK’s Avandia or to cases of antidepressants like Paxil or Zoloft that have contributed to birth defects and, it turns out, that these manuscripts were ghostwritten. Those are the most egregious cases. With regard to children, you’ve got the problem of suicidality. There is a definite association between SSRIs and these episodes where you get these uncharacteristic suicide attempts or successful suicides shortly after antidepressant therapy. Now it is tough to demonstrate a causal link between these two, but it is concerning enough that the FDA did put a black box warning on the SSRIs.

What is it like trying to get the criticism of misleading studies like this published in major journals?

I personally think that medical journals are not scientific journals. They have not acquired the same status as journals in physics, biology, and chemistry, which are rigorously critical of any kinds of results from scientific testing. Now, you’ve already got the problem that medical journals knowingly act as vehicles for misrepresentation through ghostwriting. But when you try to correct the scientific record, and you go to a medical journal with sound evidence that an article has been ghost written and has fraudulently reported data, the journals still won’t retract the articles. That happened in the case of Study 329, and it is happening right now in the case of this article that we are currently discussing that reported on study CIT 18. A major problem with this is that the article will continue to be cited in the medical literature, hundreds of times, as evidence of the safety and effectiveness of these drugs. What they are doing, in fact, is citing an article that is fraudulent.

Now, if you try to publish criticism of a fraudulent article, what you’re going to find is that you are certainly not getting published in one of the high-impact medical journals, like BMJ or Lancet in the UK, or JAMA or NEJM in the US. First, there is a very deep concern that pharmaceutical companies will file libel suits and in the UK, where the libel laws favor those allegedly defamed; they are very cautious about publishing anything that could lead to such a suit. In the US, you’ll find that the lawyers advising the journals will suggest that they not publish critical pieces like this. So this has far-reaching consequences for the integrity of the medical literature.

But, another problem is that these journals are taking on vast quantities of money from pharmaceutical companies in the form of drugs advertisements, CME courses, reprints and supplements and that is what I would consider a considerable conflict of interest when it comes to editorial decisions on critical manuscripts submitted to the journals.

So what does all of this mean for that state of the medical literature and research on psychiatric drugs?

I think that one of the most important things going on here is that we are supposed to live in an age of Evidence-Based Medicine, and physicians are keen to suggest that they have an evidence-based practice — that they are in fact following the results from the golden standard of scientific evidence, randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials.

So, how can you possibly claim to have evidence-based practice if it turns out that what you are relying upon is medical journals that are publishing ghostwritten misrepresented results from clinical trials? The vast majority of studies published are industry-funded studies. You have a serious problem here for evidence-based medicine.

What you find in pediatrics is the academic investigators in the industry-sponsored clinical trials who have prescribed the SSRIs off-label to children and adolescents see some evidence that these drugs are helpful. But then, they get negative results in the clinical trials. So now there is a contradiction. Are they going to trust their own experience or the results of the placebo control trials, that turn out to be negative? Well, you can’t claim to believe in Evidence-Based Medicine, if now you’re going to ignore the results of the trials. So this is where you get the slicing and dicing of data. The company scientists and academics investigators might start to move the outcomes around and say, “well maybe these secondary outcomes are what we really want to focus on, so we’ll just forget the negative primary outcomes and focus on this.” But, if they are looking at data in order to get it to match what they have seen in their prescribing experience, that’s got things backward. They can’t claim to be engaged in the serious scientific testing of medicine. We often see that the study drug fails to beat placebo, but often prescribers don’t consider that they might be seeing a placebo effect in practice.

When you have researchers who are seeing this glaring contradiction between the results of these trials and what they think they see in their practice, it is almost like a pilot that can’t trust the instruments on his airplane anymore. In their defense, they might really believe that these drugs are safe and effective for adolescents, but there is a sort of confirmation bias going on where they are discounting the evidence to the contrary.

*

Jureidini, Jon, Amsterdam, Jay, McHenry, Leemon, The citalopram CIT-MD-18 pediatric depression trial: Deconstruction of medical ghostwriting, data mischaracterisation and academic malfeasance, International Journal of Risk & Safety in Medicine. 2016 28[1]:33-43. (Full Text)

This means the next things to watch out for are the ghost studies that the ghost writers promote. And we thought that ghosts were without substance.

Report comment

Astonishing stuff when you read it in black and white. Corruption and malfeasance everywhere you look.

Liz Sydney

Report comment

I only wish I were surprised.

Report comment