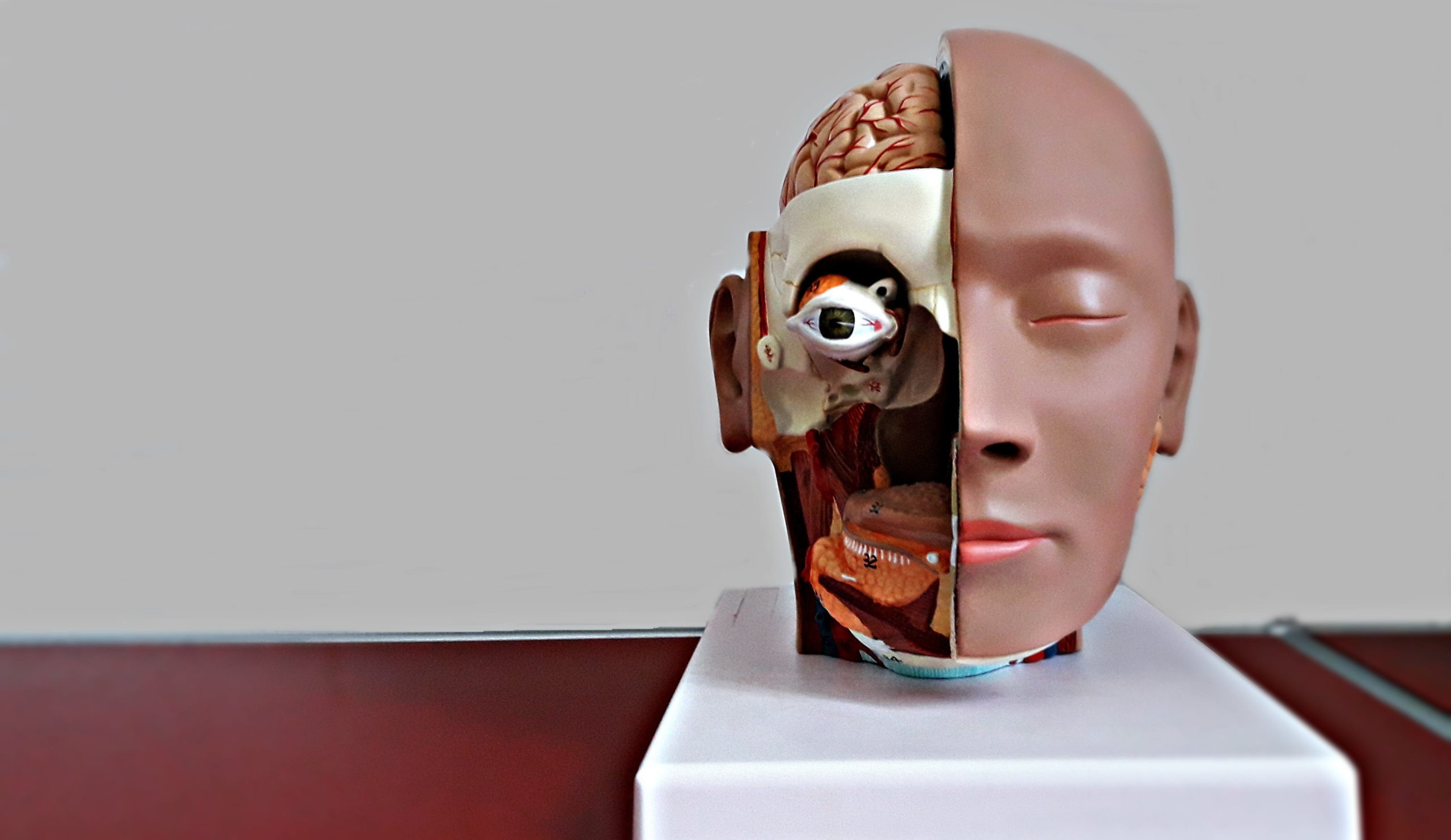

A new review of the literature, published in Medical Humanities, sheds light on crucial ethical considerations for medical professionals to be aware of when working with multicultural populations. The article highlights how the Western medical paradigm objectifies people and treats the individual as a body rather than as a human being. The author, Arild Kjell Aambø, writes:

“Although cross-cultural communication, including cultural competency and humility, has been incorporated into some [medical] curriculums, and in spite of a growing awareness of how clinicians’ stereotyping of ethnic minority patients might lead to service disparities, including barriers to access as well as less than optimal care, ethical dilemmas that might arise in multicultural settings have been largely neglected or unaddressed.”

The author draws on the writings of three European moral philosophers – Axel Honneth, Emmanuel Levinas, and Hans Jonas – to inform an approach to medical ethics that takes into account both the universal ethical guidelines that have been put into place, such as the Hippocratic Oath, as well as the personhood of the patient.

The author draws on the writings of three European moral philosophers – Axel Honneth, Emmanuel Levinas, and Hans Jonas – to inform an approach to medical ethics that takes into account both the universal ethical guidelines that have been put into place, such as the Hippocratic Oath, as well as the personhood of the patient.

He also offers an interpretation of a statement made by a Somali refugee to illustrate major ethical issues related to medicine’s care of the marginalized. He then provides a path by which we can use the understandings taken from his research to transform medical practice.

Aambø outlines dimensions through which to consider ethical dilemmas, providing further guidance to situations that never have a clear answer – even when informed by ethical codes that medical professionals are sworn to follow. These dimensions provide a way of more deeply considering the humanness of the patient and their experiences, which in turn can allow for ethical decisions that are more informed and take into account the context of the individual, rather than viewing them as a detached, isolated object.

The author describes how current medical practices render the patient invisible as they become objects to be studied, observed, and treated. He points to how medical professionals need to move toward recognizing their patients not only as patients, but also as “intelligible, worthy of love, respect, and solidarity.”

Additionally, encountering the other and all of their differences, and being open to this, is critical to ethical work, particularly with those who are radically different from us. Typically, we become distressed by the other’s difference because they are different – it causes us to feel anxious and uncertain. So, we try to make them the same or find some kind of common ground, rather than being open to their very otherness. The author argues that not running from this difference but embracing it is crucial when working ethically in multicultural settings.

Further, the doctor must create a space wherein the patient is empowered to take responsibility, which he calls ‘taking responsibility for the responsibility.’ In instances where the patient is incapacitated, the doctor can work to ensure that others around the patient can do so for them. To cultivate such an environment, the patient must be able to have a sense of ownership over both their suffering and their treatment.

A move towards ethics that incorporates the personhood and context of the individual requires attention to the voice of the patient. Aambø offers an interpretation of a quote taken from a Somali immigrant reflecting on her experience of treatment within the Norwegian medical system:

“I let them examine me as long as they wanted, but they have not told me what they have, what is happening, not have they asked me about where I am and who I am!”

Aambø identifies several themes present in his interpretation of the woman’s quote – her sense of being invisible, her alienation, and issues related to the lack of informed consent and information regarding her treatment. He couples these with findings in the research literature to point to several areas that treating professionals should be aware of and attend to when working with multicultural populations.

He points to her sense of invisibility as being reflective not only of a patient within a medical care system, but also an immigrant within a new country. Although her symptoms were attended to, she was not treated as a person, one with a host of life experiences – life experiences as a Somali refugee that are likely drastically different from that of a Western doctor.

A lack of recognition or invisibility is a common experience of persons of color, whose experience of micro-invalidations, or communications that ignore or deny their thoughts, feelings, and sense of experienced reality, can then lead to feelings of self-doubt, isolation or alienation, and frustration. Research has also tied depressive symptoms in black American women to micro-aggressions, further illuminating how experiences of prejudice and bias can significantly negatively impact the life experiences of those who are marginalized.

Others have written about how racial microaggressions can result in racial trauma, whose impacts share similarities with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Racial trauma is the result of sociopolitical trauma wherein there is ongoing exposure to race-based stress, such as discrimination or threats or acts of harm and injury, as well as intergenerational effects of centuries of colonization, slavery, genocide, and other atrocities committed against people of color.

Alienation, a second theme identified in the interpretation, is an experience common to illness, as individuals no longer experience their bodies as something that is taken-for-granted. Instead, they begin to experience themselves more like medical objects than persons. This experience of alienation can be exacerbated for marginalized individuals.

In the example of the Somali immigrant, we can imagine that a black, Muslim woman, who was relocated to a country wherein anti-immigrant beliefs have been publicized, that she might be feeling ostracized and alienated, both from her doctors and from society. This experience of alienation would make it challenging for her to take responsibility for herself, and her suffering, which, as highlighted earlier, is crucial to ethical care.

Others have identified the damaging impact that strict immigration policies, such as the inhumane Zero-Tolerance Immigration Policy instituted by President Trump, can have on the mental and physical health of immigrants – including separation anxiety and symptoms of PTSD in children who were forcibly removed from their caregivers.

A number of research studies highlight the damaging effects feelings of alienation can have on an individual’s wellbeing – with such studies pointing to the connections between isolation and mortality, smoking, and alcohol abuse.

Experiences of not belonging can become internalized and experienced as self-estrangement and powerlessness. Internalization of such feelings is associated with increased risk of coronary events, demonstrating how isolation and alienation do not only impact mental health but physical health as well.

Aambø also points to concerns related to consent and compliance, offering the interpretation that the woman’s expression that allowing the treating professionals to “examine me as long as they wanted” suggests that she is no longer invested in, and may not completely understand, the medical procedures or treatments that she may be undergoing.

This also reflects concerns about a lack of clear communication provided to the patient about her condition and the tests, procedures, etc., that are being performed on her. Again, understanding and information is key to informed consent – without it, the patient cannot agree to treatment, but instead, can only comply with or be coerced into it.

A study on the general experiences of medical encounters demonstrated that doctors tended to ignore patients’ experiences, meanings, values, and feelings in favor of their own medical knowledge, no matter what issue the patient presented with. This study revealed that although the doctors were courteous and friendly, the patients still experienced the encounter as dehumanizing and distressing. Feelings of confusion were reported as the patients had a sense that their doctors’ friendliness seemed to be hiding a more sinister objectification, which they were unable to object to.

Other research suggests that doctors tend to underestimate how much their patients desire information and overestimate how much time they spend providing information to patients. A Norwegian study shows that African and Asian patients with diabetes receive less time with doctors, but more medical tests, suggesting that perhaps medical professionals are operating under the assumption that more tests can substitute for less time with the doctor. Yet, immigrant populations, who may not be familiar with the language or culture, and subsequently the medical system, may require more time and care to ensure understanding – but sadly, are not being provided with it.

Aambø offers his perspective as a physician as well, highlighting how many doctors care and are attempting to do what they believe is best for their patients, even if they fall short in some ways. He discusses how doctors may refrain from disclosing certain information to patients that might not be relevant or may cause an undue sense of doubt or uncertainty. He also describes how the ignorance of context, like race or ethnicity, can be beneficial to the doctor, maintaining a sense of objectivity in their treatment.

This detached way of being with the patient can be protective, in it allows the doctor to focus on aspects of the person that are clinically relevant, which in turn could enable them to treat with an unbiased attitude. Yet, elsewhere, others have criticized psychology’s focus on the individual, emphasizing the need for attention to be paid to the contextual, as this is the only way that racial disparities in healthcare can be addressed.

The author suggests that a middle ground be found between treating the patient from a detached perspective of objectivity and becoming too bogged down with irrelevant details – one that attends to the patient’s differences or otherness and that includes the patient in the process, in such a way that allows the patient to feel as if they understand what’s going on, and recognized and heard as a person.

The author’s work, rather than blaming individual physicians, offers a critique of the medical field as a whole for leaving the person out of practice. He identifies changes that can be made within the medical field that will allow for transformation, particularly concerning how the field treats marginalized individuals.

Aambø’s discussion allows for an opening for the field of medicine to incorporate more humanity in its practice.

****

Aambø, A. K. (2020). Ethics in cross-cultural encounters: A medical concern? Medical Humanities, 46, 22-30. (Link)

Thank you Ashley.

It seems more and more people are fearful, dissatisfied, disillusioned with “healthcare”. Everyone talks about it, more and more “studies” erupt. More and more naturopathic clinics pop up to which only the wealthy can benefit from, or the not so well to do lose their hard earned last dollar.

For so long now, tests and pills took over, fear of death became ever more predominant, for good reasons.

It’s a horrible place for physicians too, because they elevated themselves, yet are unarmed. Many lies and innuendos are used to disregard patients, where everyone just keeps mum.

People are not just being exposed to having their dignity assaulted, but the one’s taking part in doling those indignities out, whether knowingly or not, are made harsher by partaking in the practice of bad service.

It is time for honesty, for patients allowed to be honest, for docs to be honest. Patients will not do everything they are told to do, and docs need to accept this and lower their expectations.

Doctors and patients are simply human and doctors are in a position of education to start to understand what that means.

More and more, doctors are the gateway to psychiatry, and thus it seems that is what everyone in the med field chose to do in the face of NOT KNOWING.

It is a way to have less patient load.

It is no longer safe to suffer, to be dependant. The hierarchy makes certain and every doc knows this and chooses death at home.

I think at this point we are all in a “multicultural” environment.

Report comment