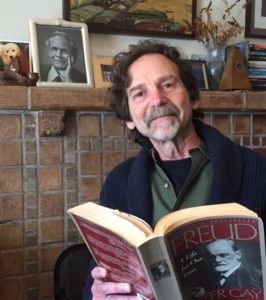

Kirk Schneider is currently running for President of the American Psychological Association (APA). He is a licensed psychologist and adjunct faculty at Saybrook University and Teachers College, Columbia University. He is well-known as the leading spokesperson for integrative, existential, and humanistic approaches to psychology, which emphasize the therapeutic relationship and the importance of confronting the deep paradoxes of being human, and the conflicts that arise from them, in psychotherapy.

He has authored or co-authored thirteen books, including the Wiley World Handbook of Existential Therapy, The Spirituality of Awe: Challenges to the Robotic Revolution, The Polarized Mind: Why It’s Killing Us and What We Can Do About It, and, most recently, The Depolarizing of America: A Guidebook for Social Healing. Many trainees in counseling and clinical psychology will recognize Schneider from the APA Psychotherapy Training video series featuring his therapy work.

Schneider is campaigning to serve as President of APA to “to address the existential crises that are now flaring all about us.” As he puts it:

“We are in crisis racially, politically, and environmentally. We are in crisis with gender and sexual injustices, and we are in crisis with mental and physical health. In short, America is poised on the precipice, and if our profession fails to grasp this problem, we are in danger of inflaming it.

In this interview, Schneider discusses his path into psychology, including his own struggles and growth, his approach to psychotherapy, and his scholarship on the psychology of awe and the polarized mind. Then we turn to his vision for psychology; a “whole-person” approach to healthcare, a “Psychologist General” of the United States, and the development of dialogue groups that address polarization and division.

The transcript below has been edited for length and clarity. Listen to the audio of the interview here.

Justin Karter: I wonder if we can start at the beginning. James Baldwin once said, “History is not the past. It is the present. We carry our history with us. We are our history.” I imagine this may be as true for personal histories as it is for our collective social and political histories. You’ve written about how the early loss of your brother deeply affected you and altered your life trajectory. How did this experience bring you into the world of psychology?

Kirk Schneider: That is a great question. I think of my history almost like a patchwork quilt that has many weaves to it.

Certainly, the loss of my brother when I was about two and a half years old and he was seven, was a huge blow; shattering to me, my family, and my parents, in particular. It was like a rip in the fabric of our day to day lives, our routines, our familiarity with ourselves and the world. I was in quite bad shape as a young kid because of that. But I had very unique parents and that probably should be noted.

Actually my mother just passed away. She was 90 years old and what an inspiration she was and is to me personally. Professionally, she was a leader, a pioneer really, for women. She had a great deal of pluck and she fought her way into becoming a leading spokesperson on radio and television in Cleveland, in the late fifties and early sixties. She always had a very expansive spirit. She believed that if you can do something, do it, you know, go for it, no holds barred. She definitely brought that fire to me. But she went through a very profound struggle and torment after my brother died. As a result, she went into psychoanalysis. She had the wherewithal to do that, which was quite unusual for that time.

She actually referred me to a child analyst who was extremely important, as I look back, in helping me find a footing in life. This was somebody outside my family system who was very seasoned. I don’t remember a word that was exchanged, but I do remember his presence. He brought a very steady, calming, and seasoned presence. I got a sense that he had been there in profound ways in his own life and that was extremely important for me because my mother and dad were having quite a challenge for a period of time.

My father was also a very unusual guy. He was a school teacher and then became a principal. His main field was science and education. He eventually became a professor of education and he did his dissertation on creativity and kids. I spent quite a bit of time with my dad, making up stories and talking into a tape recorder that he had. When I was as young as four years old, I’d be talking about the government and pollution and also stories that I saw, movies or books that I read. He was very encouraging of that.

They were both very supportive of me and helped me in dealing with my emotional life, to the degree possible. As I said, I was in some trouble for a period of time. I would go on long periods of crying and screaming and raging and had a lot of fears and night terrors. I think they did all they could to help and I’m so grateful for that.

We were the only Jewish family in an Italian German Catholic neighborhood. At that time in the early sixties, it was still pretty challenging for Jews in that kind of circumstance. I remember one time when we woke up to see a big black Nazi sign painted on our ping pong table, which was hanging in our garage. There was a neighborhood bully who would call me names, “dirty Jew,” whatever, and beat me up a few times.

I actually, I have no regrets at all about having grown up in that environment. I think it’s been part of a thread in my life, discovering the beauty, the charm, the knowledge of others.

Karter: Your latest works focus on the psychological impacts of racism, marginalization, and oppression. Being a white man in this country, it can be easy to remain in a state of obliviousness or even denial concerning issues of social justice. It sounds like you had the experience of being oppressed, but then also the experience of being the oppressor at times. You carried both of those identities at an early age. Can you talk a little bit about how your eyes came to be opened to these issues?

Schneider: Very much so, Justin. Unfortunately, that was a part of my experience growing up too. I, like many kids, wanted to identify with the crowd, with my peers.

This one time stands out in my memory, in particular, where a group of kids in the neighborhood started chasing after a kid of color in the street. He was also, I think, limited mentally and emotionally, which just added to the prejudices of kids. We were maybe seven years old. And I went along and I followed him too.

It obviously stood out because that wasn’t typical of me. I just got caught up. I remember because my father saw it from the house. He abruptly ran up to me, took me by the shoulder collar, took me back to the house, and spanked me. It was maybe one of two times that he spanked me. But it wasn’t just corporal punishment. He sat me down and he talked to me and the first thing that he conveyed was the seriousness. “Do you understand the seriousness of what you’re doing, Kirk? I mean, what if those guys were chasing you and you were this fellow running away and terrified? And what if they were chasing you because of your skin color? How would you feel? What comes up in your mind about that?” I don’t remember the details of the conversation, but I know we had had a long talk about it and it impressed me profoundly.

That was a part of a kind general upbringing that was conscious and concerned about social issues.

Karter: There you are as a young person, and you’ve lost your older brother at a very young age, and it’s clear that life isn’t guaranteed for anyone forever. You’re trying to make sense of your role and position in your community and in the world. It sounds like your parents set an example for you, and they also connected you to the world of psychology and also the worlds of literature and film. All of that helped you find your place. Not every child is fortunate to have those kinds of outlets. I wonder how it might be different for a child going through some of those same experiences that you had today.

Schneider: I’m sure radically different.

My parents were first-generation from Ukraine, Eastern Europe, but somehow they found these psychologically and psycho-socially enriching paths for themselves. I’d say I’ve been extremely blessed. It is not solely about finances either, in that many wealthy families are not raising these questions with their kids. I see this as a huge problem in our educational system generally. I think the gutting of the arts and humanities has been an extraordinary mistake in our system. I think we’re paying for it dearly all across the board in this country, in terms of sensitivity to each other and ourselves, but that’s a whole other issue.

That is one reason why I very strongly feel that I want to do what I can to support people in all kinds of situations in our country who have experienced a great deal of emotional impoverishment, as well as economic. It’s, obviously, particularly difficult to be a recipient of emotional deepening and contact when one is just striving to get bread on the table or work to scrape a living together.

This is one reason why I feel so strongly about a Psychologist General position who helps to represent psychology in a larger way, with a larger influence, and can help people gain access to quality mental health care. I’m talking about longer-term, intensive, emotionally corrective relationships. We are so deprived of this in so many settings in our country.

Karter: After having these early experiences, you found your way into the field of psychology, and then into the subfield of humanistic-existential psychology, and you studied with the famous existentialist Rollo May. How did you find your way there? What was this experience like? Did these ideas challenge you at the time?

Schneider: Again, that stems from my very unique upbringing. My dad was immersed in articles and books by Abraham Maslow, Carl Rogers, and Rollo May. All humanistically oriented. I still remember that I would play with some of these books in my playroom. They were part of a building that I would create, you know.

So I came to them very organically through conversations with my dad. It was kind of a natural evolution, growing up with a fascination with the human condition. To me, it is clear that a lot of that fascination comes out of this very early terror in my life experience that just took me into other worlds when I was very young and exposed me to these radical terrors and the unknowns of living and dying.

Fortunately, again, I had the support that could help me tap into those new worlds in a way that eventually, after a long time, got me to a place of being able to be intrigued with them and wonder about them and not just be paralyzed them. I was paralyzed by these fears for a good part of those growing up years.

Karter: It strikes me that even having confronted some of those terrors, or even tears, in the fabric of your reality, it’s still not inevitable that you would seek out the field of existential therapy, where those “unknowns” are what you continue to read about and face on a daily basis. What was that like to kind of have to intellectually meet those ideas? Was it terror over and over again?

Schneider: I like to say that I was introduced to existentialism at two and a half. I mean, basically that’s the reality.

What was it like? I lived in a scary, scary world. I was afraid of dying. I was afraid of germs. I was quite hypochondriacal. I was afraid of sort of demonic influences. I had fears of my parents as well at times. As a kid, I had all kinds of fantasies around death and almost no perspective and no layers of experience to contextualize something. Of course, your mind goes all over the place. These are a lot of the things that I needed to work through.

When I went to college, I was alone, which had its great sides in terms of being able to develop more of an inner life, creative life, imaginative life. I did make up a lot of stories and I love science fiction. Some of the programs in those days (even before college) were fantastic, at least for a kid like me.

I related to a lot of the strange worlds that were shown on shows about the paranormal, like The Outer Limits, and the early Twilight Zone episodes. They opened us up to the radical mystery of being. That’s really the path that I see that I’ve been on for 64 years. And one can be horrified by it and overwhelmed, which I experienced at significant points in my life. But you can also be fascinated with it and see it as awesome and not just horrifying and overwhelming. That’s a great place to be if one can find what I would call a ground within groundlessness, and deal with the paradoxes of that.

Those shows actually helped in a lot of ways because I was getting the other support to be able to deal with it. I was so scared of them too. My trajectory was more and more moving toward the arts and humanities. I loved English literature, drama classes, sociology classes. Then, in college, I blossomed with psychology. I had the good fortune of going to some great places to learn with people who were disciples of Maslow and some of the direct forebears of humanistic psychology.

Karter: Will you say a little bit about what humanistic psychology was about at that time. As it was emerging, it was seen as counter-cultural and it was changing psychology in significant ways. What was the culture of humanistic psychology at that time?

Schneider: The most substantive aspect of it was an attempt to try to understand the whole human being to the degree that’s possible, our whole-bodied experience of life.

The feeling among a number of the founders was that psychology had become reduced into part processes. Psychology, at that time, was focused on behavioral studies, focused on intellective changes (changes in thoughts), conditioning changes, and physiology and medical approaches.

The sense was that we weren’t really getting to understand the agentic capacity to discover one’s core values and aspirations in living, what life was about in a fuller sense, what really mattered to each individual. So this whole field blossomed from that, and it was connected with revolutionary movements in the culture in the sixties that were on parallel paths, trying to break out of the straight jackets of the Victorian era of the fifties. It was a very dynamic time but that also led to excesses, which I think are very problematic and unfortunate, but understandable.

For example, I have the greatest admiration for RD Laing and his work. I think it’s just pivotal in our field in terms of understanding, and being open to, alternative ways of seeing reality and so-called ‘psychosis’ and really blowing the lid off of our so-called ‘normal functioning’ in society. It really moved toward a much more socio-political-cosmological context for understanding human behavior and experience. But, I feel he made some mistakes; personal mistakes that had something to do with his own struggles.

That compromised the really important messages that he and others were attempting to convey to psychiatry and psychology. Some of that I think was encouraged by the excesses of the sixties with experimentalism, and not knowing what would happen if people took an excessive amount of drugs or experimented in very freewheeling ways with intimacy, etc.

Rollo May wrote a very perceptive book about this, called Love and Will, where he was calling people to acknowledge the beauty and the wonder and the absolute richness of the opening up that was going on in the sixties, but also to have some caution about the fragility and vulnerability of our humanity as well.

Karter: Sometimes humanistic psychology is characterized in terms of just focusing on the positive elements of human behavior, what might be possible, how we might change. Then existentialism is seen as overly focused on these deeper, darker confrontations with the harder to answer parts of being human. Your work on “awe” integrates both sides of this. Can you talk a little bit about how you came to develop this idea of awe?

Schneider: Integration has been a thread through much of my life and I’ve come around to it through hard experiences of my own.

I did have some of those experiences in my graduate years at the State University of West Georgia, which was one of the first real concentrations of humanistic psychology on the East coast and was created at Maslow’s blessing. I had wonderful professors there, a wonderful community, but I also struggled some with the radical openness of it. I actually had some of the most important psychotherapy and existential analysis of my life there. That was a pivotal follow-up to that earlier analysis I had as a kid, but some of my earlier issues were sort of getting activated at that time. That was extremely important and has really made me an advocate for a more holistic, depth approach to therapy.

I’ve been aware of deep fragility and humility or humiliation, if you will—a sense of smallness in my life—as well as a great capacity to venture out and to take risks. Those risks can often be extremely rewarding in one’s life, but they need to be tempered with humility about how vulnerable we are and how powerful the subconscious forces of the psyche can be; the notion of being a fragile creature before the vastness of existence.

At least for me, that dynamic or dialectic between smallness and greatness has been extremely important. I find that it embraces a vital sense of life, a holistic sense of life, which allows you to be able to be as present as possible to the deepest dreads and sadnesses as well as the most dazzling desires and possibilities. What more can one get out of life? To me, this is the gift that we’ve been handed and both are extremely important to each other. As May put it, they fructify each other. Without one, you don’t have the other in its depth and intensity and it’s a possibility for discovery. I feel I’ve been very fortunate to have been led, and to have led myself, along that road.

The sense of “awe” has been an organic notion that came out of a lot of personal experiences, professional experiences, and from seeing people getting stuck either in their smallness or in being over-identified with greatness or expansiveness. What I’ve found is that, almost invariably, these extremes that I call polarizations—the fixation on a single point of view to the utter exclusion of competing points of view—pertain to a trauma. They’re doing almost everything they can to avoid any hint of the opposite in their lives.

It makes perfect sense then to design a life around hyper-arousal and let’s say grandiosity or narcissism if one feels terribly small and imperceptible and not counting in life. I definitely see a lot of that problem in our current culture and especially among certain leaders. And I’m not just talking about one area. I’m talking about among our profession, young professionals, as well as among business, social, political, and religious leaders.

But people can also go the other way where they’re just terrified of taking any chances outside of the box because of their particular traumatic matrix. They hunker down and keep themselves small and avoid any hint of a more expansive way of living.

Karter: This conception of awe is a little bit different than other ways of thinking about helping people in psychotherapy, right? It’s not necessarily about taking up some middle position between feeling small and feeling expansive. It’s about being able to experience both of those things, simultaneously; being able to bring your experience of smallness into your experience of your potential; being able to bring your experience of your potential into your experience of feeling small.

Schneider: Yes, to the degree one can. From an integrative perspective, we realize that we all live on a spectrum of capacities and not everybody is ready for (or desirous of) that sort of fuller range of contact with these diverse experiences, within and without one’s self. I think we need to respect that.

I do think that there’s a lot of people—a lot more people than we realize—that do yearn for a much fuller and richer range of living, who are trapped in much more restrictive forms of living because of the systems that emphasize a more quick fix, instant result model of living. The sense of awe brings us, I believe, a kind of psycho-spiritual dimension.

We don’t often think about psychotherapy in this way, but I believe it can evolve from a therapy that is available for a deeper level of exploration of one’s concerns, which can then open to one’s possibilities for living. I call it an existential integrative therapy and I see it as a kind of staging ground for cultivating a sense of awe because you’re moving continually between crushing humiliation, smallness, and fragility and gradual and incremental, venturing out.

That venturing out can be with your therapist, expressing a feeling toward that therapist, anger, or sadness, allowing a more feeling-full life, or with others in your life or with regard to a project. And then, of course, there are invariably times where people become unable to maintain that venturing out so then they squeeze back in and go the other way, attempting to restrain themselves with more discipline and focus. And they can also end up going back into the original, trauma-based position.

In many ways, this kind of therapy I’m talking about, at its best, is a movement between a sense of abject terror and paralysis and an incremental intrigue and even fascination with the possibilities of a larger life. It’s that back and forth movement between terror and wonder that can eventually lead somebody to find that ground, that foothold, within the groundlessness that we all are living in. That’s the larger context of life and existence as far as we know it.

Karter: You present awe as a mode of resistance for what you term “the robotic revolution.” As you just spoke about how collective traumas and individual traumas can encourage us to polarize, I wondered about how social systems can encourage us to pull away from life and become “robotic.” What is the robotic revolution and how is that limiting our ability to live with this sense of awe?

Schneider: A lot of my recent concerns have been with the increasing technologization or technocracy of society and of our increasing reliance on the machine model for living. The digital mediates our experience between self and world—what is the cost of that?

It’s clear that we’re all becoming more reliant on our smartphones, the internet, and our computers. Now, with the pandemic, there’s even more of a press to rely on our Zoom meetings and plug into our virtual realities. By no means am I a Luddite. I don’t paint this as all bleak, but I do have a lot of questions and unsettling ideas about it that I feel are shared by many people who really think about what all this portends for our society.

In The Spirituality of Awe: Challenges the Robotic Revolution, I define a concept I call roboticism, which is the gradual attempt to emulate the machine model of living, and ultimately, the prospect that we don’t just emulate that model, but that we become that model. So an actual melding with the machine world. This is not an idle fantasy. This comes out of the work of people like Ray Kurzweil and others who are affiliated with something called the “transhumanist movement,” which, as they see it, is about the expansion of consciousness based on robotics and genetic engineering. They see this as a very positive thing and they talk about moving toward the singularity, which is the point at which you can no longer distinguish the human being from the mechanical.

Of course, we’ve seen this type of scenario in a lot of science fiction. I know that’s extreme and it’s not the reality of where we are now, but there’s certainly hints of that. I guess my sense is we really need to be careful. We need to be vigilant about how much computerization takes over our world.

Karter: In science fiction, the worry is often that we’re creating robots who have human consciousness, but it sounds like you’re saying that we should also worry about the opposite—that we achieve the mind-meld with technology, not by technology becoming like us, but by making ourselves like technology.

Schneider: There’s some logic to that. At some point, our machines are going to be so efficient that it’s very possible that it will no longer be functional to have the kinds of vulnerabilities and peccadilloes that we have as humans. You know, the flesh and blood problems that we have. And, certainly, the idea of lasting indefinitely is appealing to a lot of people.

This is part of that whole lineage of the search for the Holy Grail and immortality, and some of the themes that people like Ernest Becker warned about—striving for an immortality project, writ large. It’s extremely seductive. I understand as a human being that we all get sucked into the idea of living a more efficient life, a more convenient life, a much longer life and I’m a believer in that too. If we could supplement our flesh and blood way of living with the mechanical and that helps us live a longer and more enriching kind of life. Great. But here we get back to the problem of what’s driving this. If it’s fear, which, as I was saying before, is the driver of so much extremism and polarization, then we’re in real trouble.

I don’t think we’ve examined the collective fears that this movement has come out of enough. People like Michel Foucault have done profound analyses of these shifts. Take, for example, his focus on this major turn toward industrialization after the dark ages and the attempt on the part of at least Western civilization to do everything it could to move away from any hint of our primal relationship with nature. It was important in so many ways and led to great intellectual developments and brought rationality to the fore, which is obviously helpful in terms of improving our standard of living, and the way we treat each other, and avoiding illnesses. But the big question he raises is, did we throw the baby out with the bathwater? In this headlong striving to try to create a hyper-sanitized, controlled world, what’s the price?

Karter: As Foucault did, we can look at how this critique applies to the fields of psychology and psychiatry, right? You were talking about the seductiveness of creating models of human behavior that are more predictable than humans are themselves. Certainly, we might see that playing out in psychotherapy research, where we’re looking to create manualized short-term models, delivering it almost as a drug, and just looking at whether or not we’re decreasing symptoms defined in a very medical way. I’m wondering, how does this whole-person approach, how does this integrative approach to seeing the fullness of our human vulnerability fit? How do we integrate that view with studying psychotherapy and making sure people have the best services available to them when they go into mental health treatment?

Schneider: This is a huge question, and it relates back to this socioeconomic context that many of us are living under. If our world presses us toward instant results, appearance, packaging, and getting things done in a mechanistically efficient way, then that’s going to impact every other part of our lives. Certainly, science and psychology are not exempt.

This is where I have a lot of empathy for the position that psychology is in. To a large extent, it’s driven by this larger socioeconomic context, and pressure by funding agencies and corporations to maintain this model.

I think part of what we can bring with a more holistic, integrative perspective is the ability to recognize that this is part of our world and that it’s helpful at some levels. I believe, for instance, that people sometimes benefit greatly from medication; to get through the night, to get through the week, to get through very rough patches in their lives. Or they benefit from other kinds of physiological support or cognitive-behavioral support. There are people in life circumstances where they don’t have the luxury to take more time and to look more deeply at their whole bodily experience of life or to question how are they presently living and how are they willing to live? These are two very fundamental existential questions at the deepest levels of treatment.

So, yes, helping somebody to think more rationally or to behave in a way that is more functional in the world or to be supported by external inputs to help them stabilize their life can be extremely important. However, there are many people who are being severely cheated by this model and shortchanged, and it’s a tragedy. It’s a tragedy running right through our entire system from training therapists to the way it’s practiced in my view.

I think we can, as a field, as a profession of psychology, bring a larger perspective to this problem, especially if we develop the backbone and find the courage to stand up for the fuller offerings of our field.

We have many brilliant people in our field. There are brilliant people in these more practical, programmatic types of treatment, that tend to be focused on the medical-like research methodologies, as well as therapies that are more psycho-spiritually concerned, and therapies concerned more with the multicultural perspectives of the clients—patients that they see who don’t necessarily fit into these standardized, some would say colonized, models—as well as in those therapies that are concerned with a depth perspective, such as psychodynamic, existential, humanistic, etc.

They all have a lot to bring to the table. We really can bring the pendulum back toward a more fruitful dialectic in our field and bring our field more to a holistic perspective. But we need to use the bully pulpit to stand for our fuller science and the fuller range of our outcome research. A lot of that outcome research is done by extremely reputable researchers, such as John Norcross and Bruce Wampold, etc., who find, over and over again, that these more holistic relational contexts are pivotal to effective psychotherapy.

That great consumer reports study that Seligman did that surveyed clients about what they most appreciated about psychotherapy, found that it was these more intensive, longer-term, relational kinds of approaches that were more enduring and more central to them feeling a vitality about their life. I believe we can contribute to the whole culture by having a greater influence from our full range of offerings as a field.

Karter: The critique is made of psychotherapy that you can do the best work with somebody an hour a week, but if they keep going back into a society that’s trending towards greater inequality, discrimination, and marginalization, we might help them through that, but we’re not addressing the larger problems that are driving people to have some of the experiences that are incredibly difficult that we see in therapy. You’ve made this decision to run for President of APA to address some of these larger issues. I’m wondering if you could speak about your decision to run and your efforts to get psychology to address some of these larger, systemic, cultural issues that are affecting everyone.

Schneider: Well, it’s all about that. It’s all about bringing the voice of psychology to the national scene in a way that represents a more integrative holistic perspective.

One of my proposals is around a call for a Psychologist General. I can’t go into detail right now about that, but I’ve written about that in Scientific American and I’m continuing to develop the concept in discussions with people at APA council. Basically, it’s about having someone to be a point person who works in coordination with APA advocacy and our APA resources to be a bigger megaphone, advocating for many of the areas where we’re underserved in the population. We have a tremendous mental health crisis, from depression to anxiety, to addictions, to horrifying hate crimes, racism, suicidality, and, in many cases, despair about living in our current world.

There’s a great need to bring these resources to bear. I do think that having a representative from inside the government to focus strictly on the psychosocial aspects of mental health care is vital. Really, it seems, our time has come.

We’ve had the medical domination of that arena within the government. Why shouldn’t it be paired with the mind as well? Mind and body, you know, they go together, and they can be integrated and be coordinated. I think we need authorities that are just as powerful in the psychosocial area as well as in the medical.

I also believe very strongly in healing dialogues, and I think we can bring these to bear within our own field. I’ve called for, if I am elected, the assemblage of leaders and presidents of all our psychological divisions to come together to talk about what each specialty can offer to the crises of our times. Then we collate that data, we bring it together, and we communicate that to the larger public. Perhaps out of that comes more research and projects that are engaged by funding agencies, et cetera.

I also believe in healing dialogues in terms of their ability to bring together the various factions that we have within APA. We can bring leaders from the scientific wing and the practice wing, qualitative research and quantitative research, depth psychology and cognitive-behavioral psychology, ethnic and cultural perspectives on psychology, and more standardized perspectives on psychology. We can bring all of these various factions together to learn about and understand each other as much as possible.

What we’ve seen from these healing dialogues that I’ve been involved with nationally is that when the focus is on attempting to understand and learn about the other, it, it tends to enhance the likelihood of achieving common ground and building bridges. It’s so different from the kind of verbal flame-throwing that so easily devolves from our usual way of conversing in this culture.

The alternative is we continue the verbal flame-throwing, which is like pouring more gasoline on an already raging fire. A second alternative is to devolve into violence and war. And a third alternative is to devolve into helplessness and despair and total stuckness.

So I ask people who are very questioning of a dialogue approach, what are the viable alternatives? Certainly, I believe that one viable alternative is to make your voice heard, to engage one’s righteous indignation about the status quo. I think that’s extremely powerful. We’ve seen through many movements in history, civil rights being a more recent one, that can be a very powerful impetus for then promoting the national conversation. That is a springboard or an impetus, but ultimately we need to come to the table and talk to each other.

It’s not just about the intellectual exchange of views. I have worked on developing a one-on-one dialogue format that I call the experiential democracy dialogues and have also worked with Braver Angels, a national organization that brings groups of liberals and conservatives together for living room style conversations. For me, it’s more than learning about and understanding each other. It’s about supporting people to be more present to themselves and the other, even at nonverbal levels.

That’s the next step for our democratic process. To address the kind of social breaking that we’re experiencing right now, racially and politically, it has be more than just heady. We need supportive groups where it is as safe as possible, where structured dialogues that adhere to ground rules can take place. Otherwise, it so quickly devolves into these flare-ups.

Karter: I’m hearing the potential for the dialogues in two ways. One, you’re talking about working to create groups across the country so that people can come together and start to find common ground to face some of these challenges of racial justice, climate change, and the political crises that are facing us. Then there is also a role for healing dialogues within psychology, so that psychologists can come together and speak with an integrated voice about some of the policy level initiatives that could help heal some of these mental health crises. If psychology could speak in such an integrated voice, what kinds of policies do you think could be advocated for that would help to address some of the rising rates of suicide, anxiety, depression, addiction, etc.?

Schneider: First of all, through these bridge-building dialogues, we become a much more potent force and we can concentrate our priorities in a much more powerful way at the national level. What might we bring? One thing that immediately comes to mind is advocacy for making longer-term, in-depth, relational, emotionally corrective, therapeutic contexts available to a much larger range of people.

We have thousands of dedicated, extremely astute professionals working in the public mental health arena, but many of them are handcuffed because of the constraints that they’re under for efficiency, which is shortchanging to a lot of people. We could certainly advocate at the level of priorities and federal funding. We could point out that we do have studies that show that people getting quality mental health care, even at the levels that they’re being presented now, offsets medical costs. Imagine how many expenditures could be offset, not only in medicine, but from reducing the level of attrition in work, increasing motivation in school, decreasing prison populations and taking pressure off of the legal system, lowering recidivism, supporting people to find new leases on life and motivations for living, which could certainly have a serious impact on economic growth, and even, perhaps, on decreasing the emphasis on militaristic elements in our society.

The question again goes back to priorities. Do we fund what we know and what our science tells us about what will lead to a flourishing society in the longer run, or do we just keep patching up these holes that are cracking in the walls of our society? They’re going to blow through, it’s pretty clear.

Karter: To bring it full circle, I’m struck by how this kind of advocacy might affect a child who may be experiencing a great deal of anxiety for a variety of reasons, having lost somebody close to them or not having sufficient supports. How might this kind of advocacy at a federal level allow more children to have the sort of corrective experience with mental health care that you had as a child?

Schneider: Exactly. I want to see children have the kind of experience and support that I had as a kid, because I know I would have gone off the rails if I didn’t have that support. I was headed that way at points, especially in my early elementary school years.

I feel extremely strongly about that. I want to see others have that available to them, and it can happen. We are a productive and forward-thinking and innovative enough society to do so much for ourselves if we allow ourselves to think outside the box more and face these kinds of issues.

Karter: Is there anything that we didn’t get to touch on today that would be important to mention?

Schneider: I appreciate you asking that because as I was describing the experiential democracy dialogue and Braver Angels format, I didn’t have time to go into detail, but much of this is laid out in my recent book, The Depolarizing of America: A Guidebook for Social Healing. If people are interested in going into more detail, it is available there. People might be interested in my, my website: kirkjschneider.com, where there is a lot more about all of these themes.

*

Cover Photo: Kirk Schneider facilitates a healing dialogue for Braver Angels in 2019 (Photographer: Kathryn McDonald)

**

Justin Karter serves on the communications committee for The Society for Humanistic Psychology, which has officially endorsed Kirk Schneider for APA President.

***

MIA Reports are supported, in part, by a grant from the Open Society Foundations

It is very interesting

Thanks a lot

Report comment

Kirk I’m glad you gave this interview with MIA.

I really hope that you keep in mind that “dialogue” is really

dialogue when it is “open” and open this dialogue up

with the ones it really affects. Granted some people are not

in a position to effect change, but they will be the change and be

affected by the changes, so really how can we take our power and suggest

changes which we think they need? The APA might understand the needs

much better if conference rooms are filled 50/50 with the people

that end up being referred to as patients or clients and the other side

is referred to as professionals.

So we have to really look at what makes us experts? We don’t know about

will and fate, why did we become privileged? Why am I called an expert in that

person’s life or environment?

No way are we ever going to get anywhere unless we ask the experts in lived

experience.

Report comment

Well said, Sam, particularly your last line.

Report comment

Thanks Kirk.

I’m a feisty anti type so my comments usually shut down conversation, or

so psychiatry likes to point out. Well I’m really done indulging and talking

“rationally” because in most professional circles, it simply means “non compliant” or “distorted” or “angry, injured, holding onto grief”…

to my way of thinking, and we know how 6000 years of trying dialogue with

professionals, including real medical doctors, lawyers, has not made our world safer for anyone, most of all the non professionals.

So when I refer to myself as AP, it is not simply AP, but they are a HUGE part of it. It really is simply

“A”. Anti. I am anti the pretension of “knowing”. I am pro the admission of saying “I don’t know”. I am anti building a living or empire out of hypothesis and pretense, or unknown, unadmitted, unrealized bias.

So yes I have listened to Rollo and respect his views, and hope mine would be respected equally lol.

Here is an interesting Video that I know is 2 hours long and you are already educated and I also know how precious time is. But the thing with education and information I find in myself (even though I only have a jungle education of grade 6) the thing about education, even such as reading, listening or videos, sometimes we look and go “meh, I already know where it’s going, I don’t need this”.

But despite, I will still leave the video. Thanks for listening and reading.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MwgkvBZXum0

Report comment