Natalie Campo, MD, is an integrative psychiatrist practicing in Nashville, TN. She became interested in holistic treatment modalities in her first year of medical school at the University of Texas. In that same year, she was awarded an NIH grant to study infectious encephalitis in the Amazon Jungle. Upon her return, she sought out a physician whose primary care practice included holistic modalities, nutrition, and acupuncture. During medical school, on an externship, she started studying mindfulness and began using it with patients.

After medical school, Campo trained in psychiatry at Yale and in medical acupuncture at Harvard. She obtained certifications from the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology and the American Board of Integrative and Holistic Medicine. For many years, she taught alternative, holistic, and natural treatment options for anxiety and PTSD as a Yale faculty member.

Campo currently resides in Nashville, where she serves as a Clinical Assistant Professor at Vanderbilt and provides consultation to the Osher Center of Integrative Medicine. In May of 2017, she participated in the World’s First Congress of Integrative Medicine in Berlin, Germany. She started her practice in Nashville called Mindful Medicine in 2011 to bring safe, effective treatments to people seeking relief from anxiety, depression, addiction, and the stress of a hectic lifestyle.

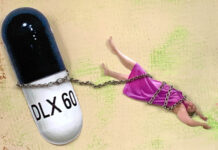

In this interview, she discusses her journey through conventional psychiatric training to holistic and integrative approaches and her experiences helping people taper off psychiatric medications.

The transcript below has been edited for length and clarity. Listen to the audio of the interview here.

Madison Natarajan: To start us off, could you just tell us a bit about your background, such as where you grew up and how you decided to go into medicine?

Natalie Campo: I grew up in a small Midwestern town. My dad traveled internationally for work, and he sometimes brought back small gifts, and he always shared stories of his travels. I became interested in cultures outside of the one I was growing up in. Once on my own, I traveled internationally whenever I could afford it.

During my fourth year of medical school, having finished my required rotations, I spent a month traveling in India and another in France. At a young age, I had decided to go into medicine long before I had had any of my own travel experiences. But when I think back, many of my hosts internationally happened to be physicians willing to share their homes and experiences with me.

Natarajan: So, these experiences abroad with different cultures really informed your interest in wanting to go into medicine. What led you to become interested in the subject of psychiatry?

Campo: I had this desire to learn about perspectives outside of my own. It also arose in part out of certain travel experience. In between my first and second years of medical school, I went to the Amazon jungle to study encephalitis inflammation of the brain caused by a very specific virus.

I was interested in the work, but I was really motivated to apply for the grant because I wanted to see Peru. I joined some students from Johns Hopkins and helped out with their study tracking the infectious spread of another disease. The time in the jungle was transformative for me. I left Peru, knowing that I wanted to study the brain and the mind. I don’t think I could have articulated it at the time, but I had had a felt sense of the interconnectedness of life while I was in the jungle.

Natarajan: It sounds like that really broadened your perspective to see things a bit more holistically, which led you to think more about psychiatry.

Campo: It did. That experience was so much more important than I could have ever known because I was nearing my clinical years—years in which many medical students lose empathy. Medical students going into medical school often are more empathetic than the general population, but unfortunately, we find that as medical students go through their clinical years and move into their residency training programs, they actually have less empathy than people in the general population.

Teaching medical students and residents about resilience led me to these studies on empathy. Empathy is important for resilience. People are more likely to bounce back from the inevitable traumas of life if they have empathy and the ability to see someone else’s perspective. But empathy decreases in clinical training. I believe this is partly due to a large number of patients to be seen and how futile some of our tools are at helping those people.

Natarajan: That’s really interesting, and I think it brings up an important part of the medical training experience. You often hear people talk about the need for doctors to have a better bedside manner. It’s interesting to learn that something occurs during their training experience. Things start to become so clinical that they’re not really making those empathetic connections that maybe they did initially when they were starting their training.

Campo: I think that the loss of connectedness is so important. Somehow that experience of being in the jungle, surrounded by the trees and animals and having had that felt experience of the interconnectedness, really impacted me in my clinical rotations.

In my third and fourth years of medical school, I found myself more interested in the person with the disease than the disease itself. I saw many examples of chronic illnesses that had resulted from failed attempts at coping with emotional distress. I remember one patient with end-stage liver disease dying because of alcohol use, dying because of an attempt to cope with life. I remember thinking if he had other ways to cope, he wouldn’t be dying this painful death, and he probably wouldn’t be alone.

I saw psychiatry as an opportunity to intervene sooner and offer tools for coping with life’s inevitable stressors. I saw it as a hopeful field.

Natarajan: Can you tell us a bit more about your various professional experiences with holistic treatment?

Campo: I need to back up a bit and say how that interest started. I saw holistic treatment work in medical school. I had the opportunity to spend a month working with a physician in private practice, where he used integrative medicine. He used conventional medical treatment models and evaluation procedures, and he also used holistic treatment models, including acupuncture. He also used lifestyle changes, like nutrition. He was incredibly fascinated and interested in the power of nutrition, and he taught me the skills and understandings of the topic.

Natarajan: In your medical training, were there any parts of it that led you to become skeptical or critical of psychiatry and its research or treatment modalities?

Campo: There were parts of my training that led me to become skeptical. I will also say that I’m incredibly grateful for the training that I had and really believe that the teaching that I received came from the physicians’ best intentions.

The skepticism came before I started my psychiatry training. I was still in medical school. I had just come off an elective with a very interesting physician, where I learned about nutrition and acupuncture in my fourth year of medical school. The patients that I was seeing with him were happy and healthy and thriving.

Then I took two months where I did two externships. I was really excited because these are my first opportunities to really work as a psychiatric intern, even though I wasn’t quite ready to go into residency training. But I was also nervous because these were a bit like month-long interviews. I had selected two externships because they were a part of triple-board programs (combined residencies and pediatric psychiatry/child psychiatry).

The first of these externships was at one of the world’s most acclaimed psychiatric hospitals. My rotation would include time on an adolescent unit. It was a beautiful campus of trees, and patients spent time outdoors learning mindfulness as part of their therapy. I was impressed already. This truly seemed like a thoughtful approach to allow for healing. But once inside, I saw some of these children holding bags of chips and cookies and munching, as they desired all day long. Maybe you think that’s great- access to familiar comforts, but I was thinking, “We’re mindlessly putting toxins into these kids.” Most of them were already obese and on medications known to cause metabolic abnormalities and weight gain. And we were encouraging processed food intake.

Maybe I am coming across as a little bit extreme about processed foods. I had recently read a study where students in schools were given simple nutrients, and those students were found to have less violent, aggressive outbursts towards other students. They were given multivitamins and fish oil. This research suggests that nutrients really do change behavior and drive symptoms.

I couldn’t help but bring this question to the director of the hospital. And I asked simply, “Can we replace junk food with real food?” His answer was, “I know, and our activities director smokes.” It was a frustrating non-answer to my simple, direct question. But looking back, I can see how authentic it really was. He acknowledged that the junk food was addictive and harmful to the body, including the brain, by comparing it to smoking. But he felt powerless to make changes for the better for his patients. I was critical of that decision, but I also felt powerless and had no authority.

On the same externship, I was working with the physician for one day. Because I was serving the role of an intern (a first-year position in training), even though I was a fourth-year medical student, I was occasionally asked to write medication orders. On this particular day, the plan was for a taper of a medication. Since I had never tapered a medication before, I asked how to do it. The psychiatrist was annoyed by this question and responded, “Just cut it in half, and cut it in half again. It’s not rocket science.”

I remember thinking, “But it is brain chemistry.” I made a mental note to learn about medication tapers and not to ask dumb questions. That was about 15 years ago. As you probably know, there is still no consensus on how to taper antidepressants. It’s still a good question.

I went into psychiatry training skeptical and critical of conventional practices. I knew going in that I would practice differently. When I was responsible for treatment plans myself, I knew that they would always be integrative, including conventional knowledge and evidence-based holistic modalities and lifestyle changes, especially real food.

My training experience in psychiatry was unusual because of that intention. While I still learned about SSRI’s, I also spent time studying mindfulness-based stress reduction and sitting with Steven Southwick, discussing the science of resilience (a pioneer in this field). Because of his generosity of time with me, I was able to create a mindfulness program to help bolster resilience in resident physicians.

I went into my psychiatry residency training skeptical of conventional medical practices, determined to learn what I could about psychopharmacology, and then to go beyond that and to think about ways to thrive and heal.

Natarajan: How often would you say clients are coming to you after being on antidepressants for extended amounts of time and are interested in getting off them?

Campo: This does happen. People call requesting consultations for assistance coming off of medications. It probably happens a few times a month. I think I’ve noticed it more as public awareness has grown about how difficult it can be, thanks to people doing work like you’re doing to help bring that to public awareness.

Public awareness has grown around how coming off of these medications can be very difficult, and as conventional consensus on how to taper these medications has stalled.

Natarajan: Since there is no standard consensus on the best way to do this, I’m wondering what your personal guidelines are for when and how to prescribe psychiatric drugs to clients. Do you typically engage in conversations about side effects and long-term use?

Campo: My guidelines for prescribing pharmaceuticals are really my guidelines for the way that I work in general. The integrative approach is always collaborative. I’m only bringing knowledge of certain modalities, including medication, but it’s really the patient who’s bringing the questions, the intentions for the treatment, the distress, the life experiences. It is only through that partnership that we can create an effective treatment plan at all.

To answer your question, when I’m thinking about prescribing pharmaceuticals, I’m always discussing alternatives. I’m always thinking about risks and benefits because medications can have so many implications and many unknown risks. I will often discuss medication with a person as a last resort, but not always. I do find them to be helpful tools.

I will often include a partner or a family member in the discussion of a medication trial. We might even look at a list of common side effects of medication together, but then since the lists are often so long for potential side effects, I will encourage a patient to think about it and read about the medication on their own in between sessions, and then to come back and sit and again and discuss potential alternatives to reassess where they are at in their life at the time, even if it’s only a few days or weeks later.

Natarajan: I think there are so many people who have the experience of coming in to meet with a psychiatrist, having a 15-minute conversation, and walking out with a prescription. You do a thorough job of getting a full evaluation of the psychosocial factors impacting this person and empowering the patient to have agency over their own decision around what types of medication they might be on. New research shows that tapering over the span of months or possibly even years is more successful at preventing withdrawal symptoms than the quick discontinuation of two to four weeks. I’m curious about what your experience has been helping clients taper off of their medications?

Campo: My experience with helping clients taper has been as individual as the interactions with the patients themselves.

That’s really because there’s so much more to what we’re doing than just tapering a medication or even just starting a medication. I really think of it as such a small part of our plan. Sometimes an incredibly helpful and effective part of our plan, but really such a small part.

It’s hard to say with certainty what effects the taper itself has on the patient. But I will say that my experiences with helping people come off medications have taught me to go as slowly as we can. It’s not always that we go slowly, but I agree with you that it’s weeks and even months or years, for some people, many people.

Oftentimes these medications have been used for a very, very long time. If we want a very effective, smooth taper, it’s often most helpful to go as gradually as possible to create as few waves or shifts as possible in the biochemistry or even the person’s habits.

Natarajan: Anecdotally, what results do you see when clients come off their medication? What changes do you witness, or do your patients report to you?

Campo: These results are also really variable, but I do want to share one example that I just remember so vividly. This was from years ago, and it’s a simple example in some ways because it was just one medication. Maybe this helps to illustrate a point about medication.

This particular patient had been referred to me by an acupuncturist. She was hoping to be able to conceive, and she was taking a benzodiazepine and didn’t want to be on the benzodiazepine when she was pregnant. She’d been taking it for 10 years for insomnia. So the acupuncturist called and asked if this was something that I would be interested in helping this patient do.

She wanted to come off before she conceived, and we did a slow taper. She had the time, and she was already doing so many things to support her emotional wellbeing. That is always foundational. If we can do other things to support wellbeing, as we’re doing a taper, it’s really essential. In fact, I usually don’t encourage people to even consider a taper unless life is going really smoothly.

This patient tapered off slowly. It took us a while, but we tapered her off, and I can remember the day that she was off completely. She came in, and she stood up. She threw her arms back behind her, and she said, “I’m free!” And I said, “What?” I didn’t know what she was talking about. She said, “I’m free of the medicine. I didn’t realize that I wasn’t [free]. I didn’t realize that it was just helping me to fall to sleep at night; rather, my body actually had become dependent on it. I had needed it. I required it. And I no longer need it!”

It’s usually not that dramatic, but that’s a fun example of how she felt. She was able to use other ways to care for herself and to allow for sleep at night.

Natarajan: Why do you think psychiatry as a field might be reluctant to confront more of these issues?

Campo: I think that it’s actually a bigger issue than just psychiatry confronting it. We really live in a culture where we are interested in quick fixes, and medication can sometimes provide a change and sometimes a quick change. Sometimes that’s very helpful, and I would go so far as even to say, sometimes it’s essential and even life-preserving, but not always. I think, culturally, we would much prefer a quick fix.

Natarajan: We want to believe that these medications can provide that quick fix. Maybe in an ideal world, they could, but it’s just not what seems to be happening.

Campo: It doesn’t seem to be happening, and it’s not sustainable. Even if there is a quick fix because of a state change from a medication, the underlying causes are not being addressed.

If we don’t ever address the root causes of depression or anxiety, the healing doesn’t happen, and it’s not sustainable. If we don’t ever search, for example, for a vitamin or nutrient deficiency, if we don’t see the psychological stressors that a person is dealing with, there’s no way. And how can we see that in 10 minutes? We can’t. We can’t even get a full picture of the person’s life, let alone look for causative agents, and then discuss alternatives and risks.

We are not allowing physicians time. The systems in place do not allow physicians time to interact with their patients in meaningful ways.

Natarajan: There would really have to be an entire restructuring of the medical field, as opposed to even just pinpointing what psychiatry needs to change. The whole system needs to be reconsidered.

Campo: I do think so. I think, for the most part, when we’re thinking about chronic conditions, the answer tends to be more medication because that is a quick answer.

You only have 10 minutes. You really only have time for quick answers. But we have a lot of problems in our society and our culture and now in our world with obesity and insulin resistance, which has led to depression for many people.

Natarajan: You use the word healing. That the concept of healing is very different than just thinking about symptom reduction. Going back to the question of “What are the root causes?” And even if we have something that can reduce symptoms, the root causes affecting other areas of people’s lives are not being looked at, not being healed. How can you do that in 10 minutes?

Campo: I couldn’t agree more. I think that’s so well said. I think that there are times when medication might help provide a reprieve or a moment to be able to reflect. But I think that, as a field, we are placing way more hope in medication than it can deliver.

Natarajan: I think it makes sense to look at it from the perspective that perhaps it’s less about what’s being said, and more about what’s not being said. For you to have the time to add these other conversations into your meetings with patients is what could make all the difference and give them a lot more information and agency over their own decision making.

Campo: Absolutely. Mostly the patients that are contacting me are already thinking in that way, and that’s why they’re contacting me. So that has been a really rewarding experience.

A patient called last week wanting a second opinion. He said that he really liked his psychiatrist that he had been meeting with for years, but he only saw him every six months. He only met with him for 10 minutes at a time, and when they met, the instructions or the directions were always to either increase his medication or add another one.

The patient said that he was tired of that kind of approach and asked the physician to help him taper. The physician was doing so, but reluctantly. So he was hoping for a second opinion, but he had also said that he had been studying on his own and had been starting to eat a real whole food diet and was already feeling so much better. That was really encouraging. It’ll be interesting to see how that turns out for him.

Natarajan: Calling yourself an integrative psychiatrist, and the name of your practice, “Mindful Medicine,” already kind of brings in a certain type of client. Is it at all professionally difficult or threatening to your career to help people taper from their medication?

Campo: I don’t think it’s professionally difficult or threatening to help a patient taper from a medication that is causing them harm. It is certainly a different way of practicing, sitting with people for extended lengths of time, and thinking through treatment modalities that are outside of conventional treatment plans. For years, it did sort of feel like I was practicing in a very different way, but many people came before me and who did this work and whose professional careers were absolutely threatened by the work they were doing.

A very famous example of this is Herbert Benson, who studied the relaxation response at Harvard many years ago. He would sneak subjects into his lab in the middle of the night and record their breathing and monitor their blood pressure and show that their blood pressure would go down with this relaxation response. But this was controversial. I mean, we all have to breathe, and it’s safe and effective for bringing blood pressure down and for helping with anxiety, but he had to sneak these people in to be able to do this research!

I don’t think it’s nearly as threatening for me to practice in the way that I practice, because I do practice with so much caution, always thinking about safety and always thinking about the patient’s best interest. To me, that is the best type of medical practice that we can have, but it is different, and in many ways, unconventional.

Natarajan: Can you speak more about the different types of treatment modalities that you’ve seen work best when it comes to treating clients with anxiety and depression?

Campo: It’s really hard to talk about this type of treatment without a patient, right? That’s because when I’m sitting with someone, I’m only bringing my knowledge of the modalities, and the person is bringing their experiences and their distress and their intentions. I’m listening very carefully to understand what the person is experiencing and what it is that they’re seeking; what type of guidance they might be requesting or thinking about.

In some ways, it is very hard to think about what the treatments are. This type of work is necessarily collaborative. But there are some very specific things that we can do. There are many easily identifiable vitamin deficiencies. People may be struggling with thyroid disease. These issues can present as depression. This is conventional psychiatry. This is absolutely taught in psychiatry residencies. However, I don’t know how often it’s practiced. I hear lots of clients who will come in and say they haven’t had blood work done in a very long time. So I want to be looking for those biological root causes because if they’re there, I want to be able to treat it. That’s important to keep in mind that integrative psychiatry is conventional psychiatry. It is also holistic psychiatry, and it also includes lifestyle changes. The Venn diagram of those three and where they converge is integrative psychiatry.

When I’m thinking about holistic modalities and anxiety, breathing techniques can be very effective. That goes back to what we were talking about with Herbert Benson. There are many different types of relaxation breathing techniques, but they all come down to one key component, and that is extending the exhale. The reason for this is that every time we inhale, we activate the sympathetic autonomic nervous system. And every time we exhale, we activate the parasympathetic autonomic nervous system. In theory, we’re in balance all day long, inhaling and exhaling, inhaling and exhaling. When we inhale, that is the sympathetic part that is getting ready, fight or flight. It is being on guard. As we exhale, the parasympathetic activates to rest and digest. It’s ease, being at peace, feeling safe.

All day long, if we oscillate between the two, we are in balance. But what do most of us do? If we’re feeling anxious, we inhale, and we hold our breath. Then we’re in a state of sympathetic overdrive, and we balance it out by exhaling. If you can really extend your exhale, you can move into that parasympathetic state. You can do that in one or two breaths. You can do it for yourself. You can notice that sensation in your body; you will become calmer.

For depression, it certainly is helpful to be able to use breathing techniques, especially if there is a lot of anxiety with the depression, but there are certainly other things that can be helpful as well. Mindfulness or nonjudgmental awareness of the present moment, a curiosity, can be a helpful practice in daily life.

When I’m thinking about depression, I’m often thinking with people about movement. It doesn’t have to be a certain type of physical exercise, but some exercise, some physical movement is absolutely helpful for depression. It increases BDNF in the brain, which is a brain-derived neurotrophic factor. And so with exercise, we will see mood improve. It might just be momentary, but once we have a habit of exercise, BDNF is building in the brain, becoming more regular.

That brings me to another piece. Habits and rhythm sleep are incredibly important. It’s foundational. If that’s the only thing I can help someone with, they will feel better. We have to have sleep so that our bodies can heal. We have to have sleep so that we can think and focus and concentrate. If we’re falling asleep at about the same time every night, and we’re waking at about the same time each day, that helps our circadian clocks. We have circadian clocks in every cell of our body, and that helps reset them. So sleep is important.

Food is incredibly important. We’ve talked about that already. Breathing is incredibly important. Moving. None of these things are new, right? I’m not telling you anything that you haven’t heard before, but it’s about actually putting them into practice on a daily basis. Mindfulness or meditation is new for some people to think about, and they are incredibly powerful and effective.

If we can have a rhythm in our life; If we can wake in about the same time every day, check-in with ourselves with a short meditation or a breathing exercise; If we can eat at about the same time every day, and we eat real whole foods as close to their natural way as possible; If we have movement every day, and we allow for sleep again at night; If we have restorative relationships, nurturing relationships.

We talk a lot about consuming toxic things in our lives, but sometimes our relationships can be very painful, and maybe we need help setting up boundaries to protect us from difficult people in our lives. Therapy is incredibly important. Unfortunately, we don’t see a lot of that in conventional psychiatric practices. The vast majority of the patients that I work with have therapists, and all of them receive some type of therapeutic intervention when they’re meeting with me.

I imagine I’m leaving many things out. I think about yoga with people. I think about biofeedback at times. I’ve studied lots of different herbs and supplements that have been incredibly helpful, but again, these are all taken in context. They’re all individualized for the person that I’m meeting with. We’re thinking about how one thing will interact with another.

Natarajan: This links to what you said earlier about the need for more structural change in medicine. It goes back to the fact that if you don’t have the time to be collaborative with your patient and learn all of these things and figure out what’s conducive to the lifestyle, you miss so much. There seems to be a culture shift that needs to happen to see more psychiatrists practicing in this way.

Campo: There is kind of a gap between what I was trained for in conventional psychiatry and what I see in common practice. However, my training with integrative work really came even before I started studying psychiatry. I was working with that integrative physician in medical school, learning about nutrition and acupuncture even before I started my psychiatry training. I knew that would be the way that I would practice when I moved into it.

I didn’t know a lot of integrative psychiatrists when I finished my residency, and I started my own journey, but I did know some. Now I am really happy to say that I know many, and there are more every day. Every year when I go to these conferences, more and more people are interested in this way of working because it works.

I’m really encouraged and excited that we are at the beginning of something that is going to be very different. It may take a very long time. I know that there are a lot of people who are really struggling and who don’t have a relationship with a provider, but that could change.

Natarajan: It is encouraging to hear that you are encountering more people interested in this perspective in your professional circles. It sounds like you do envision a future where more people are practicing in this way, but the shift may occur at a slower pace because there’s a lot of structural change that needs to happen as well to make practicing conducive to this type of work. Thank you for joining us today.

Campo: Thank you so much for the opportunity. Take care.

*

For more information on Dr. Campo’s practice, you can visit her website at Mindfulmedicinenashville.com.

***

MIA Reports are supported, in part, by a grant from the Open Society Foundations

Thanks Madison, and Natalie

Having a relationship with providers is key.

But how is that possible when the students lose their empathy? Losing empathy is paramount

to being able to view the subject before you as an object to be “done to”. Therein is the ultimate sickness.

I would surely be saddened if my child were part of a community that does not know how to help other than giving their customers harmful sentences and chemicals.

As a mother there is nothing to be proud of, knowing that harm comes from one’s child’s employ.

Psychiatry is being used, and there is no honor in being used.

Report comment

This interview is the most fascinating and informative text I’ve read since I read Anatomy Of An Epidemic. Tragically, the imperative lifestyle-related changes Dr. Campo recommends in order to achieve good health holistically, are beyond my reach at this point in my life. I’m sure this explains why I’m now dying from diabetes.

In the 1970’s, I hadn’t begun taking any psych meds yet. I frequently became catatonic and had difficulty moving around, and I don’t remember the specific steps of the helpful breathing technique I discovered on my own to deal with this. But I remember, vividly, invoking it.

Since the 1970’s, I’ve also seen that a proper and nutritious diet makes all the difference in the world, as does adherence to a regular sleeping/waking cycle. I wish that I could do these things and thereby save myself.

Report comment

Best Wishes

Report comment

There is a big problem as early as the title.

Holistic psychiatry is a glamorized amendment of people who are unable to relinquish their medical and personal status. They play the critical hero all the while displaying the same status-clinging, field-cherishing, and obliviousness as the common priest-psychiatrist. They just moved their inadequacy in the land of vitamins.

Medical skills are unsuited for the assistance of human distress. Period. There is no roundabout.

Plumbers are as fitted as doctors for that, so where are the articles about ‘integrative plumbery’ on MIA?

Medicine practitioners are not fitted for the helping of human distress. AND, because their ‘endeavour’ was so catastrophic, they are unwelcome.

Integrative practitioners have no power and will never make the Industry tremble. They are dangerous only for us, the survivors, because they can distract us with their flickering mushy ‘alternative’, which is just another system.

And systems are never good for helping people. Only good and smart people can, but they are rather rare.

Report comment

Nice comment.

Report comment

Thank you for the article. I live near Nashville and contacted Dr Campo. I am trying to get my mom to have me see her as a psychiatrist. My mom seems receptive to the idea.

Report comment

“Integrative psychiatrist”, huh? Well, I’m a pro-Jewish Nazi. I’m a pro-African-American KKK member…. I’m a pro-Democrat Republican, and a pro-Republican Democrat, to boot!….

I’m a freedom loving pro-Fascist!…. I’m a Christ-worshipping Satanist, and a Satan Worshipping Christian…. I’m a master of psychobabble, gobbledygook, Critical Race Theory, and I’m woke as all hell, man!….

Now, I’m actually going to carefully READ the article above, and when I’m done, I will return here to the comments, and see if I still agree with myself….

Report comment

It’s NOT the “integrative” part of Natalie’s story & title that is problematic. I’d go as far as to say that I do not believe that Natalie has a complete and comprehensive understanding of the past 300 – 500 years history of medicine, money, power, and control. Especially the last 100 -150 years. So I’ll repeat my mantra. “Psychiatry is a pseudoscience, a drug racket, and a mechanism of social control. It’s 21st Century Phrenology, with potent neuro-toxins. Psychiatry has done, and continues to do, far more harm than good. So-called “mental illnesses” are exactly as real as presents from Santa Claus, but not more real. The DSM is in fact nothing more than a catalog of billing coded delusions, fantasies, and victim blaming. Calling one’s self an “integrative psychiatrist” is all well and good, and a step forward for sure. But the deadweight baggage of psychiatry is an onerous burden better left behind on the scrap heap of history. The OTHER crucial, vital question Natalie seems as yet unaware of, and not asking, is more telling: “Why are so many people so sick, that they need so much “healing” in the first place!?…. Allopathic medicine in general, and psychiatry in particular, are designed to make populations sick, keep them sick, and make as much profit as possible, as long as possible, then you die. NEXT in line, please!…. All to maintain the money, power and control of the Global Ruling Elites & Global Banksters over the masses of good people on Planet Earth. I’m hoping that Natalie will be at first offended when she sees me state here that there is an absolute equivalency between “Jew-loving Nazi”, and “Integrative Psychiatrist”…. 45 years ago, now, my TORTURE with psych drugs began. I’ve been FREE from both for 25 years now. I hope Natalie learns enough of the TRUTH much faster than I did, and much less painfully. I express my sincere BEST WISHES to Natalie, in all her future endeavors…. rsvp?….

Report comment

I think it is Szasz who writes something to the effect that psychiatry (Szasz being…Szasz…he, of course, means involuntary psychiatry) cannot be reformed. It must be abolished.

I do not have any sort of “problem” with this psychiatrist, but…I don’t think psychiatry, as a field, can be made into anything genuinely “helpful,” much less meaningful…and definitely, never ever, in any way shape or form, can psychiatry somehow magically re-work itself into becoming a valid branch of medicine.

At an individual level, I am glad that this particular psychiatrist has chosen what seems to be a less toxic, less dangerous way of doing business. However, at best, that is harm reduction, and this individual psychiatrist’s pursuit of a less abusive, less damaging sort of psychiatry makes her and those like her in the field…

exceptions who prove the rule. 🙁

Report comment

One of the last actions I took as a “mental patient with a borderline diagnosis” was to contact the office of a psychiatrist in my state who advertised himself as providing “holistic psychiatry”. I called and scheduled an appointment with him, for which there was a 2-month wait and for which I was willing to pay hundreds of dollars out of pocket as he did not accept Medicare. I filled out the forms as instructed by his assistant and sent them back prior to my scheduled first appointment. The day before my first appointment, he had his assistant call me and canceled the appointment… Reason being, “he’s not taking any more borderline.”

There’s no such thing as holistic psychiatry, or integrative psychiatry, or compassionate psychiatry. It’s all dehumanizing, othering, putting a label on the patient, putting the patient in their place. That’s what psychiatry does, and in the process, destroys lives, including mine.

Report comment

Thanks for exposing that Katel.

More proof that there is no such thing as good psychiatry.

To boot, he is not even a good person.

So he goes by someone elses “diagnosis” lol.

I am really sorry this happened to you. It takes a crap load of strength to rise above

but you really do have to remember that they have their own crap. There cannot

be any other reason for these people to act out the way they do. And it really is a form of acting out.

Perhaps feel pity for them, since I’m sure it cannot be that pleasant of a life for them.

Report comment

Thanks, Sam. I hope they are unhappy. That was one small event over 15 years of hell that I went through as “a mental patient with borderline”, or, as they like to call me, “a borderline”. I had been in treatment multiple times over the course of my life prior to the borderline diagnosis but the hellish dehumanizing treatment got much worse once I had that label. From the moment the Yale psychiatrist who had recommended ECT for “treatment resistant depression” told me, “You have borderline personality disorder. That’s why the ECT didn’t work” it was 15 years of absolute hell. I doubt I’ll ever recover from the damage they caused.

Report comment

I don’t understand this article. Traditional psychiatry is integrative psychiatry is holistic psychiatry? Well traditional psychiatry destroyed my mind, body and spirit so I’ll take a pass. Maybe it’s the brain damage from all of the brain shocks and the forced/coerced polypharmacy which always included antipsychotics but I don’t understand how one thing can also be it’s opposite. If it’s about breathing exercises and eating well and having boundaries and relationships — how is it psychiatry? Do people get diagnosed by integrative or holistic psychiatrists? I don’t understand it at all.

Report comment