The history of humankind is like a maze; a collection of pathways, designed to lead us from a beginning to an end goal, with the journey entailing much retracing of steps, the occasional dead end, and from time to time that sense that we’ve all been here before — after all, aren’t those who don’t know their history doomed to repeat it?

Fittingly, the word maze derives its roots from the 13th century Middle English word mæs, which refers to delirium or delusion.

As the novel coronavirus pandemic sweeps across the world — disrupting capitalism’s hitherto ceaseless gears of production and laying waste to businesses, national economies and livelihoods — the great slowdown has brought into sharp focus the collective state of delirium we’ve all been caught up in.

As Within, So Without

So why write an article comparing a global pandemic to the experience we often refer to as a ‘mental health crisis’? Well there’s a remarkable similarity between the maze people find themselves navigating inside their bodies and their minds when they’re experiencing mental and emotional distress, and the collective labyrinth we are all now traversing as we try to find a way through the pandemic.

The Indian philosopher and poet Sri Aurobindo emphasised how first individuals needed to undergo a creative process of change or individuation, in order for society to then undergo the same process. Both the micro and the macro are reflections of one another.

The effects of The Great Slowdown are slowly changing all of us — and not just at an individual level. Society’s scaffolding is already up and major structural reworks are taking place across nations, transnational corporations, businesses and communities. The entire global economic system is undergoing a dramatic renovation, but not everybody’s onboard for change and many still mistakenly believe that a return to the way things were before the pandemic is still possible.

Not the Tomb, but the Womb

Humanity as a whole is slowly undergoing a collective process of metamorphosis. The pandemic represents a profound moment of reckoning and an opportunity for us to acknowledge and heal the collective traumas that have endured from generation to generation.

We carry the crimes of our forefathers within us; an inherited archetypal shadow that belongs to all of humankind. These ancestral wounds weep inside each of us until eventually a community of people take it upon themselves to do the healing work for the entire ancestral line, from the harrowing tales of the transatlantic slave trade crying out through the voices of the Black Lives Matter movement, to Greta Thunberg’s appeal to the World Economic Forum that, ‘Our house is on fire!’ It is within the power of any generation to atone for the wounds of the past; to put an end to the flowing stream of blood and tears.

As the renowned author and trauma specialist, Dr Gabor Maté wrote:

“The teenage climate activist Greta Thunberg has been diagnosed with a number of mental health disorders, including Asperger’s….The people on both sides of the Atlantic who have dismissed her as mentally unstable have done so in the service of denying climate change, a stupendous dissociation from reality that will never be inscribed in the diagnostic compendium of mental illnesses, despite the fact that it threatens to destroy human habitats and much of the natural world.”

Dr Maté’s sobering observation brings into question the entire notion of so-called ‘mental illness’, a conversation many in the mental health fraternity have been grappling with for decades.

Who should we say is really more ill? A person who responds in a perfectly natural way to the trauma they experience at the hands of society? Or the indifferent society that continues to locate the so-called ‘disorders’ and ‘illnesses’ within the people that it harms, rather than in itself?

We have codified the symptoms in an ever-expanding manual of mental health disorders as though the symptoms — depression, anxiety, altered states, etc. — are the thing. But they are not the thing, they are the signposts pointing us to a deeper truth, the harbingers of the much needed wisdom being offered to us as we experience this period of collective suffering.

If we pay close enough attention, the purpose of these signposts becomes apparent. We suffer because we need to change. We suffer because Nature itself, of which we are an inextricable part, deeply wants us to heal, both individually, as a species and as a planet.

Our suffering lessens when we begin to understand that the pain we experience has both a meaning and a purpose. Healing takes place as we develop the capacity to move towards what at times can feel unbearable.

It’s a delicate process of unfolding, like the petals of a flower, and while it cannot be forced or rushed, certain conditions can allow it to take place. At an individual level we must first sense compassion present in another, before we allow ourselves to venture down that painful pathway that leads to truth.

Experience vs Behaviour

My colleagues and I went through an intense and transformative process during our training to become psychotherapists. For five years we sat in a circle one weekend a month and shared our deepest pain; expunging grief and trauma like water from a sponge.

SafelyHeldSpaces.org was founded on the principle that everybody should be supported to go through whatever it is they need to go through without somebody trying to tell them what that is, enabling them to journey through their own personal rites of passage in life.

In the field society calls ‘mental health’, far too much of the focus is on people’s behaviour — even when, as observers, we know very little — if anything at all — of people’s experiences.

To truly meet another person beyond the prosaic level of the behavioural, we must first find a way to move out of the rigidity of our own mind, our own fixed assumptions and beliefs. Crucially, we need to understand just how quickly our judgment of others takes us out of relationship with them.

As the renowned countercultural psychiatrist and author R.D. Laing wrote in the 1960s in his book The Politics of Experience and The Bird of Paradise, “experience is invisible to the other…natural science is concerned only with the observer’s experience of things. Never with the way things experience us.”

The antidote to judgement is curiosity and attention. And while judgment is often the bedfellow of fear, in a neurological quirk of the human species, our brains are incapable of experiencing fear and curiosity at the same time.

When we allow ourselves to bring a sense of curiosity to a person’s experience, all judgement begins to melt away. And almost magically, new layers of the person’s inner world begin to reveal themselves to us. What’s often being asked of us is to simply be with what is and to listen deeply.

The American Poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow says, “if we could read the secret history of our enemies, we should find in each man’s life sorrow and suffering enough to disarm all hostility.”

As we find ourselves at a time in history where all too quickly friends are becoming enemies; where common ground is giving way to partisan divides, the 200-year-old poet’s words seem remarkably current.

Creating a Roadmap to Guide Us

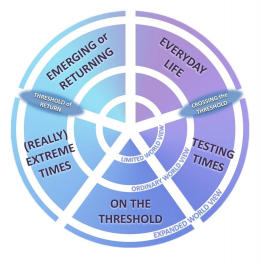

In order for us to begin to expand our curiosity about a person’s inner experience, it’s useful to first have a map of the territory we might encounter. One of the first things Safely Held Spaces did was create a roadmap to help people begin to understand the various stages a person may experience on their journey.

From everyday life, into the realms of testing times and really extreme times, each stage of the roadmap helps us to navigate our way through a confusing, and at times frightening, experience.

The expanding circles on the diagram represent the concomitant worldviews, or the lenses through which we understand the world; the cultural baggage that we inherit, and the shared truths and assumptions we unquestioningly accept as a given.

A commonly held, albeit limited worldview (see innermost circle on roadmap) of mental and emotional distress is that it should not be happening; that it’s an aberration to be cured.

But as we begin to expand our worldview to include an understanding of how inner transformation takes place, an appreciation of the nutrition hidden in the chaos begins to unfold.

“For a seed to achieve its greatest expression, it must come completely undone. The shell cracks, its insides come out and everything changes. To someone who doesn’t understand growth, it would look like complete destruction.” — Cynthia Occelli

The seed within us contains the plan. As the mythographer and author Robert Lawlor writes, “the seed disembodies itself to objectify its internal forms and forces. Germination is an explosion, the unified body of the seed vanishes into the duality of the root and stem. Somewhere inside itself an acorn knows how to become an oak.”

Tending to Our Garden

For seeds to grow to the fullest of their potential, they need to be tended to. Writing for the BuildBackBetter initiative by CompassOnline.org.uk, the co-chair and gardener, Sue Goss, suggests humanity needs to make a fundamental shift away from machine mind and towards something more akin to garden mind.

Goss suggests that like good gardeners, we might shift our focus to creating a state of equilibrium; tending to our communities — our gardens — as opposed to trying to control them.

She speaks of the need to “respond to people in vulnerable circumstances with love and kindness; to encourage creative expression; and to respond to people as individuals instead of ‘units of service’”.

She notes how an antiquated system means even the most well-intentioned projects may constitute wasted time and money, and ultimately merely be addressing symptoms instead of root causes.

In Greater Manchester a campaign has been launched opposing the redevelopment of Park House Psychiatric Hospital, which community groups say held no public consultation on the model of care it would be providing.

As Goss highlights, ‘machine mind’ assumes that we can build something to ‘fix’ the problems and continue as usual, build a hospital to warehouse the human collateral damage of our broken society, when what’s actually needed is root and branch systemic change — a paradigm shift.

Community groups in Greater Manchester who are opposed to investing new money in an old paradigm say they want a model of support for people in crisis that promotes autonomy and recovery and respects human rights, and that crucially, provides care closer to where people live and their networks of support.

This might take the form of community hubs and sanctuaries open late into the evening, crisis centres like Bristol Sanctuary or Leeds Survivor Led Crisis Service, which have adopted compassionate models of support and are paving the way for a better way of meeting people in times of distress

To Return, or to Emerge? That Is the Question

An experience of crisis often brings with it an opportunity for growth. In Mandarin, the word for crisis is composed of two characters, one representing danger and the other best translated as an ‘opportunity’ or a ‘change point’. To live through a period of crisis is to live through a moment of dangerous opportunity.

In both the pandemic and a journey working through mental and emotional distress, talk of ‘recovery’ implies returning to the way things were before — paving over the cracks, literally ‘re-covering’ them — even when that means returning to the things that precipitated the crisis in the first place.

The process of emerging is more akin to a kind of metamorphosis. A caterpillar emerges from the darkness of the cocoon forever changed, possessing new capacities and insights, and as it takes flight as a newly born butterfly, for the first time it begins to take in an expanded perspective from greater heights.

Metamorphosis, that is to say personal growth and transformation, can look and feel like destruction at the beginning. Without guidance and a roadmap of what to expect on the journey, the process can feel annihilatory. Once this threshold into an expanded worldview has been crossed, once we have emerged as somebody different to who we were before, there can be no going back — no remaining in the safety and comfort of the cocoon, however appealing it might seem.

All of us hold the potential to grow and move from a limited worldview to an expanded one — to spread our wings, so to speak. But emerging is by no means an easy task and requires the support of those who have already undergone the process before us.

A New Paradigm to Frame Personal Growth and Transformation

Our collective vision for the world post-pandemic will depend greatly on how many of us resist ‘re-covering’ and returning to the business as usual that threatens to destroy us and the planet.

For a person undergoing the enormously challenging internal experience of emerging into a new way of being, ‘re-covering’ can feel like the less terrifying and perhaps only possible option.

Furthermore, the process of emerging is not an individual choice, but rather the product of fertile conditions coming together at the same time to open up a way forward. These conditions are created in a community with strong bonds and relationships, a community that understands how to hold others in their distress.

There are also personal and relational factors influencing the emergence process that may be outside of our control, creating a very difficult push-pull dynamic. This process, which can at times feel unbearable, is at the heart of what we traditionally refer to as a ‘mental health crisis’.

So what does it take on a practical level to emerge through this difficult process and avoid returning to the way we were before? Emerging requires us to open up to feelings of terror, grief and shame and associated memories and felt sensations in our bodies that we have denied.

At times these memories and sensations (often labelled as anxiety, depression, disorders, etc.) are so unpleasant that we feel as though they might totally overwhelm us if we let them in. We find strategies to defend ourselves against them, and we use any number of addictions to numb them.

For example, how many of us would be prepared to acknowledge our own racist thoughts? Our own capacity for cruelty? How many of us have the capacity to sit with our own pain and to truly befriend it without pushing it away? How many of us can sit with another’s pain when there’s no simple way to make that pain stop?

Friends and family may also struggle to understand the journey we’ve embarked on. If on the outside we seem to be falling apart (breaking open), they may be terrified and want it to stop, but fail to understand that the process we’re undergoing is one of transformation, and not an illness to be cured.

They may even feel confused or threatened when it becomes apparent that we’ve changed, or may not like the new person who emerges from this process — particularly if that new person serves as a mirror reflecting back to them the parts of themselves they’ve avoided facing. They may want us to simply ‘get back to normal’; to ‘re-cover’.

In many families the person who is experiencing the so-called ‘mental health difficulties’ is manifesting deeper problems rooted in unresolved issues that belong to the entire family network, and even to the society or community as a whole.

In order for incremental changes and healing to begin to take place, it’s important that an experiencer’s close network begin to move beyond notions of ‘fixing’ or ‘treating’ the person, and instead agree to embark on their own parallel journey of growth and transformation.

For these kinds of parallel journeys to take place, our entire mental health system must be reimagined and imbued with an expanded worldview; one that doesn’t impose definitions or seek to translate the meaning of an individual’s experience on their behalf.

It’s also important to think about the language we choose to use. As clinical psychologist Dr Lucy Johnstone notes, even the very term ‘mental health’ is problematic in that it implies its opposite, so-called ‘mental illness’. Many who have emerged from their personal journeys transformed choose to use very different language to describe their experience.

In place of the word ‘patient’, Safely Held Spaces uses the word ‘experiencer’, and in place of the term ‘carer’ we use the word ‘holder’. During Safely Held Spaces holders weekly meetings, we have come to understand that the material being addressed by the experiencer and the holder is not separate, and that the wellbeing of one person depends on the other.

The Open Dialogue model, originally pioneered in Lapland in Finland, and now being run in a handful of NHS Trusts in the UK, has had some remarkable results. Open Dialogue centres on bringing the experiencers and members of their extended network together for ‘whole system’ or ‘network meetings’.

One of the psychiatrists spearheading Open Dialogue in the UK, Dr Russell Razzaque, says that it’s the dialogical conversation itself, which sits at the heart of the model, that serves as the crucible through which healing takes place. He describes it as a “forum where families and patients have the opportunity to increase their sense of agency in their own lives.”

Safely Held Spaces’ roadmap lays out three worldviews, or ways of understanding, experiences of crises. These worldviews apply both at an individual and societal level.

Limited Worldview

When we hold tightly to our limited worldview, we resist the change a crisis brings and we want things to return to exactly how they were before. This leads us into tighter and tighter places of denial, and causes us to resist how things really are, to fight back against the inevitable process.

Ordinary Worldview

An ordinary worldview considers the meaning of our experiences in the context of our past and of the society in which we live, it sees that some things may need to change, but these changes are adjustments to the existing paradigms of the families, communities and societies in which we live, rather than completely rethinking them. A half entry into the cocoon, but no transformation.

Expanded Worldview

An expanded worldview, represents a more open position, a willingness to change what needs to change, to look for new meaning. A willingness to consider a range of possible options outside of existing paradigms, embracing uncertainty and being willing to step into not knowing, but trusting in ourselves and our emerging knowing. Being prepared to go deeply into the darkness, even when it feels difficult or frightening.

It’s not just people that fall apart when they undergo change; societies do too. There comes a point for all of us when we begin to apprehend that the things we considered to be certain, solid and dependable are — like everything else in the universe — subject to powerful forces of change.

The structures of our societies, our global economy, the rules and customs that give us purpose and meaning are no exception to this inevitable fact of life.

As the turbulent waters of change sweep us all downstream, widening out a new channel, the old ways fall away into the raging torrent. Any attempt to swim back up the river is futile….what was once there before is no longer.

The question is, can we learn to swim in the middle of the river? Can we help one another to stay afloat through this great transition? Can we become open and curious, instead of fearful or judgemental, about our individual and collective experiences?

A collective paradigm shift is no easy task. It requires a dramatic change in the way we relate to one another. It requires us to open ourselves up to really feeling what is happening, instead of trying to push the discomfort away.

As the author of The Empath’s Survival Guide, Dr Judith Orloff, said in response to the pandemic: “It’s a very sacred and beautiful transition we’re going through on Earth.”

The Collective Psychology Project speaks of humanity being on the precipice of two futures. In one possible outcome we contract into a place of fear — the breakdown scenario. It’s the scenario that will lead to climate scarcity, tribalism and eventually the collapse of entire ecological systems.

A return to business as usual greatly risks this scenario becoming a reality.

The second scenario is one in which we emerge from this crisis with a renewed passion for community. This is the route to a future of collective safety through connection. It holds the possibility for restoration and will ultimately lead to our societies flourishing.

The British cultural anthropologist, Victor Turner, speaks of the notion of Communitas, an unstructured state in which all members of a community are equal, allowing them to share a common experience.

This era of Communitas may still be in its embryonic stages, but what is undeniable is that all over the world antiquated power structures are now in a state of collapse; suggesting that something new is beginning to emerge.

From the European Union, to transnational corporations and even the fragile unity of the United Kingdom, the structures globalisation bequeathed to us will not remain as they have done since the end of the Second World War, 75 years ago.

And far from being the catastrophe many of us have envisaged, these tectonic shifts may be an important step in the dismantling of power structures which no longer serve humanity at its current level of collective intelligence. Things fall apart, so that they can then fall into place.

The distinguished author and professor of sociology Boaventura de Sousa Santos asks, in his article Virus: All That Is Solid Melts Into Air, what potential knowledge can be garnered from the coronavirus pandemic?

de Sousa Santos notes that since the 1980s, the world has been in a permanent state of crisis, a crisis which has been used to justify ongoing austerity, including cuts to health, education and social welfare.

Unbridled economic growth, whatever the cost, may just be costing us more dearly than we could have ever imagined. Perhaps that’s why Mother Nature has found a way to put on the brakes.

Cherishing the Collective

The very etymological root of the word pandemic is ‘all people’, so isn’t it about time we began to truly cherish the collective once again? American author Rebecca Solnit says the elevation of individuals to the status of heroes means as a society we celebrate the few instead of the many, “pity the land that thinks it needs a hero, or doesn’t know it has lots and what they look like.” She adds:

“We are not very good at telling stories about a hundred people doing things, or considering that the qualities that matter in saving a valley or changing the world are mostly not physical courage and violent clashes, but the ability to coordinate and inspire and connect with lots of other people and create stories about what could be and how we get there.”

The function of a healthy society should not be to elevate a small number of people into the stratosphere, whilst abandoning others to fend for themselves. The current disparity between those who have, and those who do not, is emblematic of our own inner poverty; our spiritual bankruptcy.

Our apathy to unrestricted greed and materialism, the shredding of the collective fabric that holds all of us together, blinds us to the shared misery that takes place when that community fabric is torn apart. Without some restraint, some concern for those at the bottom of the trickle-down system that underpins the global economy, all of mankind ultimately pays a price. Nowhere has this been more evident than during the pandemic.

The Compass paper Towards A Good Society speaks of how a good society could allow people to flourish throughout their lives, “with special emphasis perhaps on childhood and older age as periods when people are more likely to be dependent on others.”

When we understand the interconnectedness of our global community, and the consequences of the fabric of community being torn, we can begin to understand that those who have been labelled as ‘mentally ill’ are in fact a barometer, sounding the alarm. They are far more healthy than the society they’ve been forced to endure; a society that has expected so much, and yet offered so little.

The Mentally Initiated

We must ask ourselves: Has the coronavirus pandemic really been the cause of all the damage to our economies and our societies? Or has it simply shown us just how damaged and damaging the global economic system really is? Just how broken our societies already are?

And if it’s taken something as tectonic as a global pandemic for us to begin to face the reality of our broken global system, what will it take for us to begin to acknowledge the victims of that system, those we have labelled as ‘mentally ill’?

South West England’s Former Head of Community Mental Health Services, Paul Wilson, says far from being ill, those moving through the rite of passage we’ve labelled ‘mental illness’ actually have something very important to teach us.

“Don’t the so-called ‘mentally ill’ possess the very qualities necessary to ensure our survival as a species? Don’t they demonstrate the value of alternative states of consciousness, increased self-awareness and a sincere desire to change? Don’t we need those very qualities right now?”

The positive benefits reaped from The Great Slowdown may not become apparent for years or even decades to come, but research carried out by Britain Thinks over the course of 2020 suggests the lionshare of Britons do understand that a return to the way things were before is simply not an option, and that there is an urgent need to invest in health and social care

The Financial Times editorial board laid down the challenge, writing that the government must start to see public services as investments rather than liabilities. “Radical reforms — reversing the prevailing policy direction of the last four decades — will need to be put on the table…Policies until recently considered eccentric, such as basic income and wealth taxes, will have to be in the mix”.

Inoculating Ourselves Against the Truth

At the time of writing this article in early 2021, a national Covid-19 vaccine programme is being rolled out across the country. It stands as a testament to the power of the collective.

But even as a light appears at the end of the tunnel in the form of a jab, we witness many in government paralysed, unable to face the reality of what needs to be done to move from an idea of recovery to one of emerging anew.

As Extinction Rebellion’s co-founder Gail Bradbrook noted in a recent presentation, our wounded society is one of separation and consumption, where domination, division and corruption have become the lingua franca, and where infinite growth at any expense goes unacknowledged as a suicidal act: a cancer.

The global economic system in its current form is creaking under the weight of its own hypocrisy; the pandemic has simply accelerated the ultimate fate of any system predicated on infinite growth instead of equilibrium and balance.

Even Margaret Thatcher, one of the great proponents of neoliberalism, conceded in a speech to the United Nations in 1989 that, “we should always remember that free markets are a means to an end. They would defeat their object if by their output they did more damage to the quality of life through pollution than the well-being they achieve by the production of goods and services”.

And whilst the damage to the global economy has left us all shaken, the universal consensus across the scientific community is that a failure to act quickly on the impending climate emergency will lead to an ecological and economic demise far worse and more frightening than anything we’ve witnessed during the pandemic.

Emerging From the Maze

The world is still finding its way through the maze presented by the pandemic, our seemingly robust systems of finance and business capsized by a microscopic nucleic acid genome — girded by little more than a protein coat and a membrane.

In the H.G. Wells novel The War of the Worlds, microscopic organisms save the human race from alien invaders. It’s a story that seems strangely prescient — mankind ultimately saved by germs…in the end. Whilst the pandemic has been an immensely difficult time for all of us, it’s also been the catalyst for much needed changes in our society.

In a world hurtling dangerously out of control, teetering on the precipice of self-inflicted ecological collapse, rent asunder by rampant individualism, Covid-19 may come to represent a turning point in history, a moment when humankind was offered a new pathway.

Sue Goss’s idea of garden mind replacing the old machine mind provides a beautiful allegory for the paradigm shift Safely Held Spaces is working towards. When we’re tending to our gardens, we don’t plant seeds and expect to reap the rewards right away. We understand that a good garden requires patience and a longer term vision. That it depends on a multitude of conditions all coming together, and a group of people working collectively.

Tending and nurturing, is a very different approach to diagnosing and treating. We don’t try to fix our gardens, we need only work in harmony with nature and allow things to grow and emerge at their own pace.

Our mental health service and our global economy both currently function on a machine mind mentality, the limitations of which are currently being laid bare for the world to see. It’s a painful process, but just like painful mental and emotional experiences serve to transform us, a pandemic provides us with the opportunity to reimagine a completely different society and to Build Back Better.

Someone is sitting in the shade today because long ago somebody thought to plant a tree. We too must have that long term vision for our communities, we too must strive to sow the seeds for plants whose flowers we may never see in full bloom, but which we know will lead to lush landscapes for years to come.

Victor Turner says we journey through what he calls liminality as we move from one condition of our life experience into another.

The liminal — or the ‘in between place’ of thresholds and transition — can be a terrifying experience. Somewhere between caterpillar and butterfly, no longer one, but not yet the other, it can be hard to trust that we’ll emerge from the process, or even that there is a process.

Liminality constitutes the middle stage of a rite of passage where we no longer possess pre-rites status, but where we’re still yet to emerge as the changed person we become when the rite of passage is complete.

Turner’s concept of Communitas is characteristic of people experiencing liminality together, a shared journey of growth and transformation.

As the vaccine is rolled out, it’s clear that we all must play our part in restoring health to our communities. But in our rush to ‘return to normal’ it’s important that the lesson offered to us at this moment in history isn’t lost: that the normal that so many of us cherished, wasn’t normal at all. It was a ‘normal’ that caused great harm, both to individuals and the planet itself.

A vaccine may provide a brief window of opportunity to move forward, but there will always be new strains, other mutations, more collective challenges to confront. And unless we begin to act in harmony as a global community, we will once again all pay the price, and quite possibly undertake this entire journey all over again. We will not emerge, we will return.

But if we’re courageous enough to imagine a new era of Communitas, and take steps towards it, then we may just emerge from this pandemic with the wisdom it intended us to understand. That mental and emotional equanimity, much like halting the spread of the virus, depends on the actions of society as a whole, as much as it does on the individual. And that ultimately, I cannot be well, unless you are well too.

Since this qualifies as a “covid” blog let’s start with some breaking news, if the Wall Street Journal is sufficiently immune from being classified as “conspiracy theory” (note — this is intended as GOOD news, no one should find it threatening): https://www.wsj.com/articles/well-have-herd-immunity-by-april-11613669731

Report comment

Oldhead

In London (UK) the cases have supposed to have dropped by very large figures as well. So there must be “something” happening.

Report comment

https://www.standard.co.uk/news/london/london-coronavirus-cases-borough-latest-figures-covid-b920405.html

” … London.. Infections down 90%…”

Report comment

Uh oh. This is going to rain on someone’s parade. But they’re probably going to claim it’s because of their lockdown measures.

Report comment

It’s also important to think about the language we choose to use:-

On my Comparatively Recent Medical Notes I can see entries like:-

1. “No new sign of hearing voices”,

2. “Eye contact normal”,

3. “No sign of neglect”

4. “Currently functioning”.

BUT in the 35 years that I’ve been in the UK:-

1. I have Never heard voices

2. My eye contact has Always been normal

3. I have Never suffered from neglect

4. And, I have Always functioned

Report comment