A study from the Netherlands recently found that despite numerous high-quality publications casting doubt on stimulant treatment for ADHD over the past 20 years, prescribing rates did not change. Instead, prescribing rates fell only after two major documentaries were released.

“The increase in medication use for children with ADHD in the past 20 years is alarming, although there appears to be a slight decrease in recent years,” the researchers write.

The researchers suggest that changes in the evidence base for psychiatric drugs do not lead to changes in prescribing. Instead, media efforts are necessary to bring these findings to the general public, which can pressure doctors to follow the evidence.

The study was led by Maruschka N. Sluiter at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands and focused on the use of methylphenidate (Ritalin), which is by far the most prescribed stimulant in Europe. Their data came from the Dutch pharmacy prescription database IADB.nl, which includes prescription data on about 600,000 people.

Sluiter writes, “There was little evidence that publication of new evidence directly influenced the use of methylphenidate.”

According to the researchers, the Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD (MTA) provides the most relevant information. The MTA was a large and rigorous study run by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) that compared four groups: medication, behavior therapy, the combination of medication and therapy, and usual care.

Although the first publication of the MTA in 1999 appeared positive for stimulant treatment, later publications of long-term MTA results in 2007, 2009, and 2017 found that stimulant treatment was associated with worse outcomes.

If prescribing patterns followed the published evidence base, one would expect to see a significant boost to stimulant prescribing around 1999-2000, and significant decreases when the negative long-term results were published, such as in 2007-2009.

However, Sluiter’s study found that prescribing trends seemed unrelated to these changes in the published evidence for stimulant treatment.

“The incidence shows an overall increasing trend, with two periods of decline that appeared unrelated to the MTA publications. The proportion of long-term users was relatively stable over time at approximately 50%, while the duration of use was increasing, despite the publication of evidence that does not support long-term efficacy.”

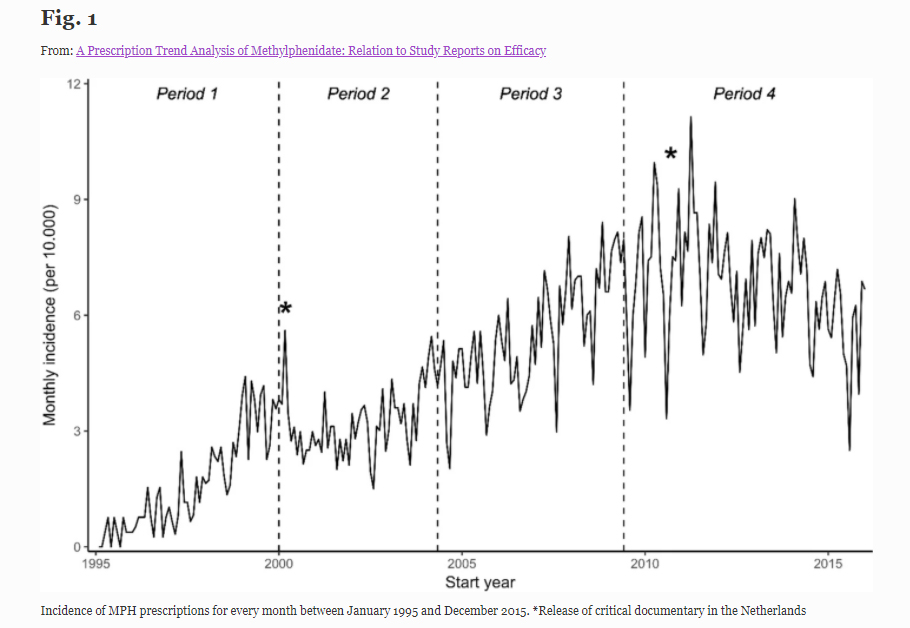

The researchers looked at the prescription of stimulants in the Netherlands between January 1995 and December 2015. Overall, prescription rates skyrocketed during this period, even quadrupling from 2003 to 2013.

Interestingly, the two periods of declining use happened around 2000—contrary to expectations, just after the positive MTA results were published—and around 2011, when no MTA findings were published.

Interestingly, the two periods of declining use happened around 2000—contrary to expectations, just after the positive MTA results were published—and around 2011, when no MTA findings were published.

Why would prescription rates have declined in the Netherlands in 2000, just after a large positive study was published, and continued increasing in 2007-2009, while powerful negative studies were being published?

According to the researchers, it could be because media documentaries influence prescription rates, while actual scientific evidence does not. A major Dutch documentary critical of ADHD and stimulants was released in 2000, just before prescription rates fell. Another was released in 2010, just before the 2011 drop in prescriptions.

According to Laura Batstra, a co-author on the study and notable ADHD researcher,

“[The study] taught me an important lesson: if our research shows findings that are of immediate importance to the general public, it is not enough to communicate these results in scientific journals. Research papers, especially those that disconfirm initial spectacular findings or prevailing opinions, do not automatically translate into adjustments in clinical practice.”

The researchers also found that prescription rates also dropped precipitously in the summer months (when the children were on vacation from school), indicating that stimulant treatment was only believed to be necessary for specific situations (getting children to pay attention in school), rather than as a treatment for a brain disorder.

The first MTA publication, in 1999, presented short-term outcomes. In that study, it appeared that stimulant treatment was superior to therapy or usual care. Based on this publication, guidelines recommended stimulant treatment over therapy.

However, multiple follow-up studies of the MTA have been published—since it was intended to study long-term effects as well. By the 22-month mark, the benefits of stimulant treatment had disappeared.

A three-year follow-up paper confirmed this finding—none of the groups were doing any better on ADHD measures than the others. In fact, “the MTA medication algorithm was associated with deterioration rather than a further benefit.” The MTA researchers also found that children’s growth (both height and weight) was stunted when they took stimulant medications.

This finding was also consistent at the six-to-eight-year follow-up. The MTA researchers concluded in their 2009 paper that “the MTA participants fared worse than the local normative comparison group on 91% of the variables tested.”

The most recent paper was a 2017 publication of the 16-year outcomes for MTA participants. The MTA researchers concluded that stimulant treatment stunted children’s growth but did not reduce their ADHD symptoms:

“Extended use of medication was associated with suppression of adult height but not with reduction of symptom severity.”

****

Sluiter, M. N., de Vries, Y. A., Koning, L. G., Hak, E., Bos, J. H. J., Schuiling-Veninga, C. C. M., . . . & de Jonge, P. (2020). A prescription trend analysis of methylphenidate: Relation to study reports on efficacy. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 47, 291–299. (Link)

This is very telling!

This must mean that it takes public pressure to change private habits.

Professionals get into ruts and then get complacent about it. Even they need a kick in the butt to change!

Report comment

What it means is that the doctors are not prescribing based on scientific evidence. They are motivated by different factors, including keeping parents happy, feeling like they are “doing something,” fitting in with social expectation, and/or increasing their personal income, to name a few possibilities. It is not a problem of information or knowledge. It is a problem of improper motivation.

Report comment

to basically steal from Szasz, yet again…

psych ‘treatment’ changes more based on…dogma, funding, social factors, economic factors, and…did I mention funding?

I think this includes the doctors who engage in acts of psychiatry, while (thankfully…) contributing to society by specializing in…wait for it, wait for it…-real medicine- .

i highly doubt educating affluent, well-educated, powerful guild members in an effort to encourage restraint will do…much, of anything, at all. based on the history of uppers by prescription…and quaaludes…and barbiturates…and the neuroleptics…

expensive, publicized lawsuits, license revocations, perhaps putting Dr.Speedy McSpeedball in prison (and televising it) -might- help…

with controlled substances — especially with the mental health guild– legislation is crucial. the US love affair (middle class and up, mostly white) with ‘pep pills’ and ‘goof balls’ and…on and on and on…didn’t start to truly fade until ritalin and the amphetamines were put in Schedule II in 1970. even then…

the decade of coke and downers for those with sufficient means and inclination had -already begun- . I’m guessing that, with the myth of ‘ADD/ADHD’ firmly entrenched, even in the real medical specialties that do, in fact, -know better- , one might expect a drop in prescribed uppers…

when some new, ‘safe! effective!’ treatments come out, preferably on patent and with a glitzy marketing campaign. then, expect to hear that Speed Kills! (again), till…

next time. 🙁

Report comment

Even by their own rules, these drugs don’t have any positive effects in the long run. This is not new news – Russell Barkley himself found this out way back in 1978! So why doesn’t anyone know this?

Report comment

Because people who mention that the drugs have no long term benefits and only cause harm are stigmatized, fired, censored, and/or slandered. There is a price that is paid by those speaking truth to power. Few people will take that price, especially when they’ve been initiated into the group, or are using defective brains as scapegoats.

How many people have told or pressured someone they cared about to “to seek help” or “take drugs”? In order for that group to admit psychiatry causes only harm they’d have to recognize the harm they did.

When the options are scapegoat defective brains, or be retaliated against for admitting psychiatry with your aid committed horrid atrocities, people will usually pick the former. They will defend it mindlessly and abusively because avoiding guilt is a powerful motivator.

Report comment