In a recently published study in PLoS One, researchers investigated the effects of long-term exposure to both literary and popular fiction on various aspects of social cognition. They found that reading literary fiction predicted a greater ability to understand the psychological lives of others in more complex and accurate ways.

The study was led by the social psychologist Emanuele Castano from the University of Trento in Italy. The authors write:

“As children, we listen to (and fabricate) stories all day long, and as adults, we end the day by reading, watching, and increasingly by playing stories. We love stories because they are entertaining, they teach us about the world we live in, and, just as social interaction, help us to build the cognitive processes needed to learn about the world. Scholarly work in evolutionary theory and anthropology suggests that stories played a significant role in the evolution of human cognition. Over the past decade, research has investigated the processes involved in the mental construction of fictional worlds, how readers are transported into such worlds, and the impact which engagement with fiction has on cognition.”

The authors distinguish between literary and popular fiction, which attracts readers for different reasons and has different socio-cognitive functions. Popular fiction is thought to be entertaining, an escape from everyday reality where the reader follows primarily plot-driven stories with relatively evident meanings and themes. On the other hand, literary fiction is known for having more complex, introspective character-driven stories narrated from multiple perspectives. Readers are encouraged to construct their own meanings from the story’s events.

The authors distinguish between literary and popular fiction, which attracts readers for different reasons and has different socio-cognitive functions. Popular fiction is thought to be entertaining, an escape from everyday reality where the reader follows primarily plot-driven stories with relatively evident meanings and themes. On the other hand, literary fiction is known for having more complex, introspective character-driven stories narrated from multiple perspectives. Readers are encouraged to construct their own meanings from the story’s events.

“A consequence of this emphasis on inner life is that literary fiction highlights the subjective over the objective, uncertainty, and multiplicity over certainty and singularity. Another related consequence is that readers are invited to pay greater attention to the workings of the mind. While all fiction requires understanding characters’ embedded mental states, literary fiction ‘make[s] the reader infer implied mental states in addition to (and sometimes instead of) spelling some out.’”

The authors hypothesized that since literary fiction encourages a more complex reading of human psychology in its stories, it would translate to readers’ understanding of themselves, others, and their worlds. Past experimental research has demonstrated that literary fiction enhances theory of mind, or the ability to think about the psychological worlds of ourselves and others.

Following this research, the authors sought to explore what other features of social cognition might be influenced by reading literature. They hypothesized increased attributional complexity, reduced egocentric bias, and increased accuracy in social perception in people who read literary fiction.

Attributional complexity refers to one’s understanding of human behavior as affected by interpersonal interactions and other external forces and motivated by a penchant for complex explanations. If readers of literary fiction are engaged in more perspective-taking, they are less likely to fall prey to the false-consensus effect (an egocentric bias) of overestimating how similar others are to ourselves in how they behave and what they value. The researchers consider that in reducing egocentric bias, literary fiction can also enhance our accuracy of others’ mental states (thoughts, emotions, attitudes, etc.) at individual and social levels.

The researchers recruited a sample of 502 participants through the Mechanical Turk (MTurk) crowd-sourcing platform. From the 477 participants included in the study, they completed various measures to assess their exposure to the different types of fiction (literary, popular) and those for attributional complexity. Participants also completed tasks related to egocentric bias, social and mind accuracy (Reading in the Mind Eyes Test). Finally, researchers used multiple regressions to measure the correlation between exposure to literature with these features of social cognition.

From these analyses, the researchers reported that:

“Exposure to Literary and Popular fiction positively and negatively predicted attributional complexity, respectively. For both egocentric bias measures (TFC and PCTF), Literary was a negative but only marginal predictor, while Popular was not a predictor of either measure. For accuracy measures, exposure to Literary fiction positively predicted both Mind Accuracy and Social Accuracy, while exposure to Popular fiction did not predict either.”

Castano and colleagues also looked at how other factors such as level of education and gender might relate to these variables. For example, they found that participants with higher education had more exposure to both literary and popular fiction, had higher levels of attributional complexity and mind accuracy.

Additionally, females had similar patterns with the addition of higher social accuracy, though no gender differences were found for egocentric bias. When controlling for these two factors, the researchers didn’t find any change in the patterns other than exposure to literary fiction being a more reliable predictor of egocentric bias.

According to the authors, these findings are important because they build on findings of past studies that examine how fiction shapes social cognition and impacts cognitive style. In addition, they are consistent with findings that show attributional complexity positively associated with mind/individual and social accuracy, as well as a perception by peers as possessing more social wisdom and thoughtfulness.

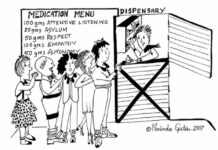

The authors mention that understanding predictors of attributional complexity could be important in mitigating racism and shaping attitudes towards important policy-related opinions.

“Yet, even though this rationale is consistent with previous work that is experimental in nature, because of the correlational nature of the data presented here, we caution against drawing strong conclusions about causality. Our view is that reading different kinds of fiction fosters certain socio-cognitive processes and cognitive styles relative to others, but we also agree that individual differences in these processes and styles may make people more prone to gravitate toward different kinds of fiction.”

They mention that it’s possible that ones’ level of education, and specifically university major, can affect their exposure to literary fiction, leading to improved socio-cognitive skills. However, the authors also caution against assuming an inherent superiority of literary fiction, as attributional complexity is related to delayed or derailed decision-making and negatively related to mental health. In contrast, egocentric bias is positively related to mental health.

Citing Terror Management Theory, which suggests that many of our actions are motivated by an unconscious fear of death (i.e., existential anxiety), the authors speculated that literary and popular fiction have opposite effects on this anxiety.

“One of the most important psychological mechanisms through which we keep this existential anxiety at bay is cultural worldviews: conceptions of reality that imbue life with stability, order, and permanence. Cultural worldviews are elaborated and maintained within cultural ingroups through a variety of cultural artifacts, among which is fiction. Given the characteristics of literary and popular fiction discussed above, we would predict that exposure to popular fiction (because it confirms expectations about the world) reduces existential anxiety, while literary fiction (because it challenges such expectations) enhances it.”

The authors contextualize the underlying socio-cognitive processes associated with literary and popular fiction as essential to facilitating core social processes of binding with others and individuating; they suggest that being in a constant self-other dialectic helps society to flourish. Binding facilitates the forming and maintaining social groups through the development of social identities and identification with and enactment of social roles. Individuating directs attention inwards and fosters a view of the world in terms of unique individuals.

“From this perspective, a hierarchy of fiction is meaningless because both binding and individuating is needed not only at the societal level for human societies to function and evolve but also, when directed inward, to satisfy intra-psychic needs.”

****

Castano, E., Martingano, A. J., & Perconti, P. (2020). The effect of exposure to fiction on attributional complexity, egocentric bias, and accuracy in social perception. PLoS ONE, 15(5), e0233378. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0233378 (Link)

It is always encouraging to see academics discover something that seems true to me, while at the same time discouraging to see them cling to assumptions that are (to me) obviously false.

It is true that this is just a correlative study. To test more strongly for causation, you would have to request (force?) the group to change their reading habits for a period of time, and measure them before and after. Do I have better “attributional complexity” because I have read more literary fiction, or did that trait attract me more strongly to literary fiction? In the “modern” world of psychology, we do need to recognize the fact that personality traits can be prior to this-life habits.

Though the authors insist on referring to “evolutionary psychology,” a subject I find singularly useless, I can understand the attractiveness of it, for it furnishes a plethora of superficial explanations. Their ambition to “help society flourish” is intriguing in its uniqueness. Who in these difficult times ever expresses this sentiment? I wish them luck in achieving it!

Report comment