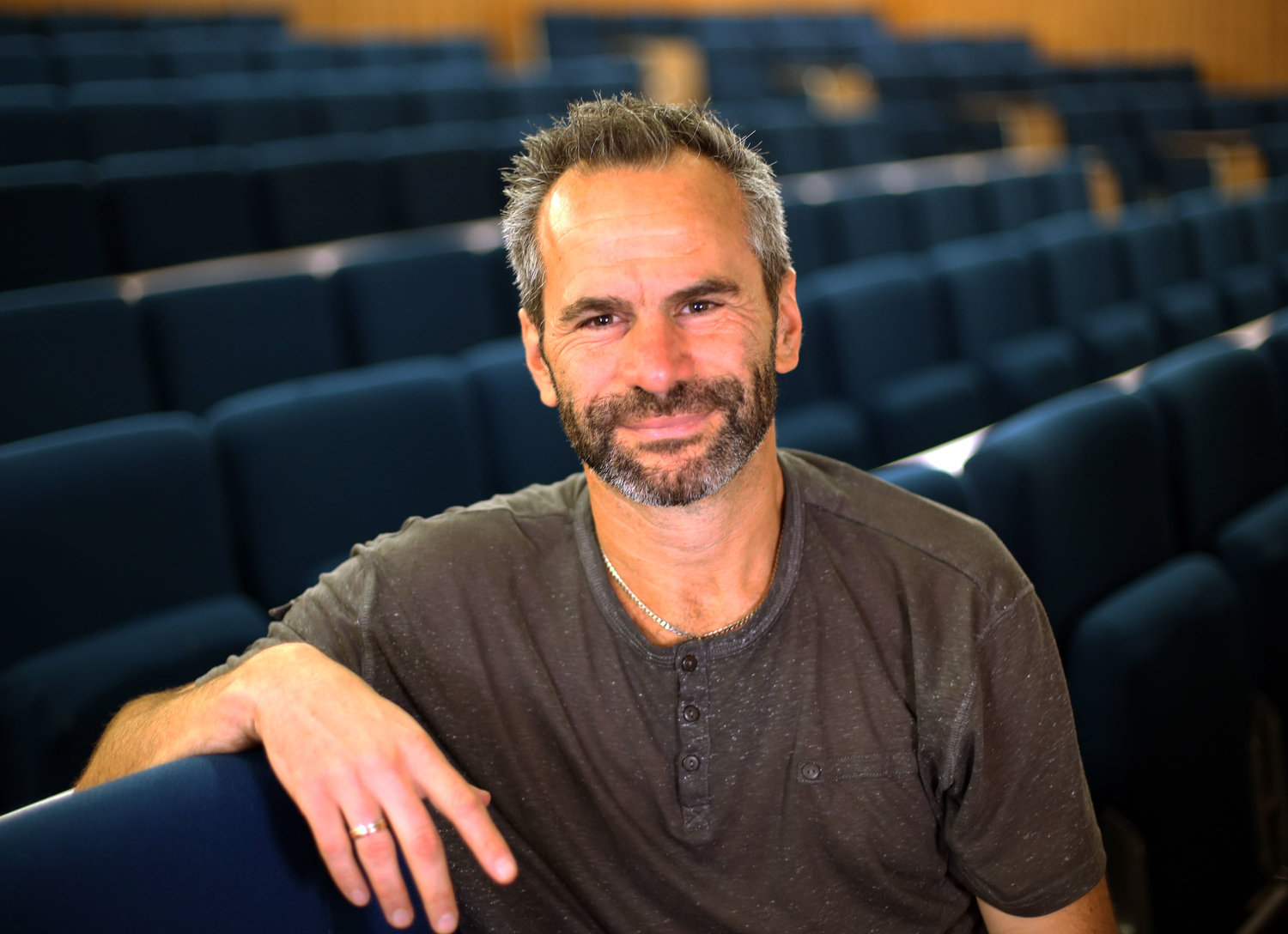

Mick Cooper is a leading voice in contemporary counseling psychology, known for his work at the intersection of psychotherapy and social change. A Professor of Counseling Psychology at the University of Roehampton in the UK, Dr. Cooper is both a researcher and a practicing therapist, exploring how psychotherapeutic principles can contribute to broader political and societal transformation.

As a co-developer of the pluralistic approach to therapy, Dr. Cooper has been instrumental in advancing a model that prioritizes shared decision-making, client preferences, and integrative therapeutic practice. He serves as Acting Director of the Centre for Research in Psychological Wellbeing (CREW) and is an active member of the Therapy and Social Change Network (TaSC). His research focuses on humanistic and existential therapies, client engagement, and the role of psychotherapy in fostering personal and collective agency.

Dr. Cooper’s latest book, Psychology at the Heart of Social Change: Developing a Progressive Vision for Society, examines how psychological theory and practice can be leveraged to create a more equitable world.

In this interview, he speaks with Mad in America’s Javier Rizo about the intersections of therapy and politics, the importance of pluralism in mental health care, and the future of counseling psychology as a force for progressive change.

The transcript below has been edited for length and clarity. Listen to the audio of the interview here.

Javier Rizo: I’d love to explore the different areas of your work. Some people might see them as quite distinct, but I’d be curious to hear about your journey—how you became interested in these different areas and how you see them as connected.

Mick Cooper: Like many people involved with Mad in America, I come from a progressive background. My parents were both politically active, engaged in issues of social justice and the broader question of how to create a fairer, more equitable society—one where rights and freedoms aren’t reserved for the privileged few. That foundation was deeply influential as I was growing up, even as my own politics evolved over time.

When I went to university, I knew I wanted to do something that contributed to society. I was drawn to psychology and eventually moved into the world of counseling and counseling psychology. But even as I worked with people one-on-one, those social justice concerns remained integral to my practice.

I was particularly drawn to person-centered and humanistic approaches, especially person-centered therapy, because of its emphasis on the value of the client’s voice. It challenges the idea that the clinician is the sole authority and instead prioritizes listening to clients and taking their perspectives seriously. Rather than a hierarchical model, it assumes that people have the capacity to address their own problems when given the right conditions. My work on relational depth and the development of person-centered and existential therapies has been rooted in this idea of a more collaborative, non-hierarchical relationship—one that centers the client’s voice and experience.

In both my practice and my writing, I’ve tried to articulate these social justice elements. But beyond that, I’ve also grappled with the larger question: How can psychology contribute to addressing the profound inequalities and marginalization we see in the world? That question became particularly urgent for me during a period of personal reflection, when I asked myself what I truly wanted to say while I still had the opportunity. I realized that my deepest passion is exploring how psychology, therapy, and counseling can contribute to a more socially just, caring, and cooperative world.

That commitment remains central to my work. While most of my research focuses on mental health treatment, psychiatric institutions, and psychotherapy, I’m also deeply concerned about the broader state of the world. I read the news every day—wildfires in the U.S., conflicts in the Middle East and Ukraine, poverty in the UK and beyond, and the staggering wealth inequality between a small elite and the millions struggling to get by. The question that drives me is: How can the work we do in the therapeutic field contribute to addressing these challenges?

My latest book, Psychology at the Heart of Social Change, is an attempt to articulate ways in which psychological discourse and practice—particularly within the humanistic tradition, where I’ve always been most involved—can make a meaningful contribution. Thinkers like Carl Rogers have long suggested that psychology has a role to play in fostering social transformation. Of course, therapy alone isn’t enough. Economic and political changes are also crucial. But I believe psychotherapy has something valuable to offer, and I hope we’ll discuss that further.

Ultimately, I see my work as a continuous thread—bringing social justice concerns into the therapeutic world, and then considering how the therapeutic world can, in turn, contribute to broader social justice efforts. Many people in psychology, psychiatry, and therapy care deeply about these issues, but the demands of daily clinical work can sometimes make it difficult to engage with them on a larger scale. As my career begins to wind down—or perhaps not—I feel a strong urgency to contribute something meaningful before it’s all over.

Javier Rizo: You’re talking about the role psychology and psychotherapy can play in progressive politics, and I’m curious about your own journey. How did you first get involved in humanistic psychology? It’s an interesting field—both mainstream in some ways and marginalized in others. How did you find your place in it?

Mick Cooper: As an undergraduate, I first encountered the work of Carl Rogers, the American psychologist who wrote primarily in the 1950s and 60s. Rogers was one of the founders of humanistic psychology, and his ideas represented a major departure from the expert-driven model that dominated psychology at the time. He emphasized the strengths, wisdom, and knowledge that clients themselves bring to therapy, developing what he initially called a non-directive approach in the 1940s, which later became client-centered therapy.

Rogers’ work wasn’t just about therapy—it extended into social change. In his later years, he became deeply involved in peace movements and mediation efforts, even bringing people with opposing views together in Northern Ireland to foster dialogue.

Reading his work as a student had a profound impact on me. What stood out was his challenge to professional authority and his insistence that clients are the experts on their own lives. His humility as a clinician was striking, and that humility became a central value for me. But what resonated just as deeply was his emphasis on authenticity—the idea that we often present a persona to the world that isn’t true to who we really are. Like many people in their early twenties, I read that and thought, Wow, that’s really true. On a personal level, it meant a great deal to me.

These ideas intertwined with my political background as well. One of Rogers’ core principles was unconditional positive regard—the belief that every person has intrinsic worth and should be accepted without judgment. This resonated with the progressive values I was raised with. But at the same time, I noticed a contradiction in the political discourse around me. My parents were quite radical in their politics, advocating for equality and fairness, yet I sometimes saw deep judgment toward those who held different views. Their vision of equality seemed to apply at an economic level, but not always at a psychological level. In Rogers’ work, I found what I saw as a deeper form of progressivism—one that valued people as equals not just in material terms, but in their humanity.

As you mentioned, Rogers occupies an interesting position in psychology—he’s both widely recognized and, in some ways, marginalized. Surveys of American psychologists have identified him as the most influential figure in the field, even more so than the developers of CBT. His ideas about the importance of the therapeutic relationship are now so embedded in the field that many therapists don’t even recognize them as uniquely person-centered anymore—they just see them as fundamental to good practice.

That said, psychotherapy research has moved beyond Rogers in some important ways. We now have a much better understanding of different methods and techniques that can help people. I believe Rogers would have welcomed that progress. He was never rigid in his thinking—he was always open to new insights.

However, in my experience, certain corners of the humanistic and existential therapy world have at times been quite dogmatic. Some practitioners seem to treat what Rogers or early existential therapists wrote in the 1950s as if it were set in stone. Ironically, the human growth movement—dedicated to the idea of change and development—has stagnated in some ways. Meanwhile, other approaches, like CBT and third-wave therapies such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), have continued to evolve. That’s one reason they’ve been so successful.

When we developed pluralistic therapy, we wanted to bring those humanistic principles into the 21st century. The core idea behind pluralism is that there are many effective ways to help people, and therapy should be tailored to each client’s specific wants and needs. Rather than prescribing a fixed set of techniques, we emphasize collaboration—talking with clients to understand what works best for them. This builds on Rogers’ client-centered principles, but in a more flexible, integrative way.

The pluralistic framework values a wide range of methods—from CBT to psychodynamic, existential, and humanistic approaches—recognizing that different clients need different things. And sometimes, that means using quite directive techniques. We’ve done research with young people in therapy, and many of them want direction and guidance. That preference should be respected rather than dismissed. Listening to what clients need and responding accordingly is at the heart of this approach.

Javier Rizo: You’ve really highlighted the aspects of psychotherapy—especially humanistic psychotherapy—that inspire you and connect with your political values. I wonder how other therapists have encountered the political potential of psychotherapy. Do they recognize it? Your book begins by discussing the neglect of psychology within progressive politics, but I wonder if the reverse is also true—has this political vision been overlooked even within humanistic psychology itself?

Mick Cooper: I think the U.S. is leading the way in this area. There’s been some outstanding work on multicultural and social justice competencies for decades now. When I speak with colleagues in the UK, I often encourage them to read the Multicultural and Social Justice Counseling Competencies developed by Ratts and colleagues in 2015. In the U.S., there are people in the counseling field who now talk about multicultural and social justice work as a “fourth” or even “fifth force” in psychology. It’s a hugely important movement.

The work of Mad in America also fits into this broader tradition, following in the footsteps of thinkers like R.D. Laing and others who have challenged the power structures of psychiatry. In the UK, colleagues like James Davies have taken a similarly political approach in their critiques of psychiatric systems and power imbalances.

However, in mainstream clinical and counseling psychology—and in psychotherapy more broadly—the political dimension often remains implicit. I do believe it’s there, though. You can see it in Rogers’ work, in the respect for clients, in the emphasis on the therapeutic alliance and the fundamentally collaborative nature of therapy. Most therapists I meet have an underlying progressivism in the way they work with clients. But translating that into a more explicit engagement with politics and social justice has been a slower process.

I think part of the reason for that is practical—therapists are focused on their work, their clients, making a living. There hasn’t always been the time or space to extend those values into a broader political conversation.

That’s one of the reasons we set up the Therapy and Social Change Network (TaSC) in the UK. There’s been a lot of interest in it—people have really engaged. We’ve had great discussions online and even organized a conference when the war in Ukraine began, raising money to support Ukrainian psychologists. Many people in the field want to contribute to this kind of work. I haven’t encountered much resistance to it.

That said, there are some small groups—especially in the UK—who push back against these ideas, framing them as “wokeism gone mad.” Their argument is that therapy should simply provide a neutral space for clients, not engage with politics. They’ll ask, “Why are you bringing politics into therapy? Why would you tell clients how to vote?” But I think those perspectives are fairly marginal. There have been a few books written from that viewpoint, but I don’t sense much energy behind them.

Overall, I believe the field is moving in the direction of greater awareness and engagement with social justice issues. The challenge is finding the resources and time to fully integrate that awareness into practice. Training is a key issue—bringing these discussions into the education of therapists, counselors, and psychologists.

Professional bodies are already on board with this shift. The British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy (BACP) has developed strong competencies and guidelines on these issues. The UK Council for Psychotherapy (UKCP) recently held a conference focused on politics and social justice. And within the British Psychological Society (BPS), the new chair has been very active in pushing these conversations forward. It feels like an open door—many people are eager to explore these links between therapy and social change. The question is how to do it in practice.

One area where the U.S. has been doing important work is around broaching in therapy—the idea that a therapist might explicitly invite discussion of a client’s identity. For example, saying something like, “This is a space where we can talk about your experiences as a Black person, as a woman, as someone who is gay.” The intention is to signal that these conversations are welcome and important.

But I think the next step in this work is to explore its complexities. When is broaching helpful, and when might it not be? When does it create space for a client, and when might it feel imposing or unnecessary? These are the kinds of nuanced discussions we need to have, and they require time—time to reflect, time to study, and time to evolve our approaches.

Javier Rizo: Yeah, historically, psychotherapy hasn’t really been a discipline that explicitly grapples with the political dimension…

Mick Cooper: I’d push back on that a little. If you look at figures like Alfred Adler, Wilhelm Reich, and Eric Berne—who developed transactional analysis—you’ll see that many early psychologists and psychotherapists were quite progressive. Adler’s work, for instance, was deeply rooted in social justice and the question of how to build a more equitable society.

There’s actually a long history of engagement with these issues. The journal Psychotherapy and Politics International has been running for many years. And of course, there’s the work you’re doing, what Mad in America does, and the legacy of people like R.D. Laing, who wove together psychology, psychiatry, and politics in profound ways.

That said, I agree that this hasn’t always been the mainstream thrust of psychotherapy. But there are significant movements—liberation psychology, community psychology, and other emerging fields—that are explicitly working at the intersection of therapy and social justice.

So, while there’s still a lot of work to be done, I actually feel quite optimistic about this area. And I don’t feel optimistic about much these days—but on this, I do.

Javier Rizo: You’re right—there have always been strands of this thinking within the field, even going back to its beginnings. I can imagine Freud would have had something to say about this as well. We’ve been discussing psychotherapy as a discipline, but I’d love to hear more about the specific principles that you see as applicable to progressive social change. Given your framing of the “world on fire,” how do you think some of the practices we use as therapists could actually be implemented in the real world?

Mick Cooper: Earlier, I mentioned unconditional positive regard, but I think the phrase radical acceptance captures it even more deeply. One of the most important things we can take from psychotherapy is its understanding of how to relate to others—not just on an individual level, but on a broader social and political scale. A politics rooted in radical acceptance isn’t about shaming, criticizing, or putting others down—it’s about valuing people.

One of the ways we can implement this is through social and emotional learning programs, which are already well-supported by research. If we were to roll them out more widely, children from a young age would learn to listen, empathize, and understand not only their own emotions but also those of others. This would help them grow into adults who can engage in dialogue, work through conflicts, and interact in cooperative, caring ways.

That’s not to say radical acceptance means condoning harmful behaviors. It’s not about saying racism, homophobia, or violence are acceptable. Rather, it’s about recognizing the fundamental humanity in each person. Very few people do harm simply for the sake of being bad. People certainly engage in destructive, self-destructive, and antisocial behaviors, but as therapists, we understand that these often stem from unmet needs—frustrations, traumas, or deep-seated struggles.

Radical acceptance means recognizing that, at the core, human beings are striving for the same fundamental things—connection, self-worth, meaning, pleasure. We don’t have an inherent evil inside us. And if we start from that understanding, we can develop ways of engaging with each other that move us toward cooperation rather than division. That’s the foundation for creating a world where more people can get more of what they need, more of the time.

One of the ideas I explore in my book is Game Theory, which teaches us about the power of cooperation. We live in a world where cooperation isn’t optional—it’s essential. Climate change is a perfect example. We exist in an interconnected system where one nation’s decisions on fossil fuels don’t just affect them—they impact everyone. Without global cooperation, we end up in destructive cycles.

This is where psychology can help—by fostering a politics of understanding rather than a politics of blame. It’s about moving away from demonization and toward collaboration. And at the core of that shift is developing a mindset of radical acceptance—recognizing the humanity and intrinsic value of others.

Of course, that’s easier said than done. One of the biggest challenges is holding onto radical acceptance while feeling anger, fury, or grief about injustice. When we see harm being done, it’s difficult to still recognize the humanity of those responsible.

In Psychology at the Heart of Social Change, I wrote with progressives in mind. My argument is that a progressive politics rooted in blame—one that operates from a stance of we’re right, you’re wrong—is ultimately self-defeating. If we want to build a world based on respect, empathy, and understanding, we have to take the first step. And that’s incredibly hard. I struggle with it myself. But I also believe it’s a pathway to hope and possibility—and right now, we desperately need both.

When you look at psychological theories and research, there’s remarkable consensus about what human beings fundamentally need. Across different models, relatedness and connection emerge as core human needs.

People thrive when they have meaningful relationships. Studies show that those with strong, intimate connections experience lower levels of depression and anxiety, and even have better physical health. The impact of good relationships is profound.

But often, our ways of seeking connection are indirect or self-defeating. We compete with others, try to prove we’re better, or push people away out of fear. In therapy, much of the work is helping people untangle these patterns—helping them understand what they truly want and guiding them toward healthier, more effective ways of getting there.

For instance, someone may deeply crave intimacy but also fear being hurt, perhaps due to past relationships. So, they keep people at a distance, avoid vulnerability, and suppress their emotions. As a therapist, you recognize why they’re protecting themselves—it makes sense. But you also invite them to consider other possibilities. Maybe they can try letting someone in, just a little. Maybe they can take small steps toward trust. Therapy provides a space for people to explore these choices in a way that feels safe.

This same principle applies to society at large. If relational needs are so central to well-being, then we have to ask: What can we do as a society to cultivate meaningful human connection?

Of course, relational needs aren’t the only needs we have—people also need autonomy, freedom, and self-esteem. But one of the things I discuss in my book is the idea of synergies—situations where different people’s needs can be met together rather than in opposition.

Relational needs, in particular, have incredible synergy. Unlike individualistic pursuits—where one person’s success might come at another’s expense—connection is something that can be mutually reinforcing. The more one person feels close to another, the more the other person feels close as well. Love, care, and deep relationships create a ripple effect of fulfillment.

In writing my book, I found myself coming back again and again to relationality. The idea of relational depth—that profound, meaningful connection between people—holds enormous promise, not just for individuals but for society as a whole.

If we could build a society that prioritized relational and communal needs over individualistic ones—if we could shift away from the relentless pursuit of self-esteem and competition—we might create a world where more people have more of their needs met. There is so much untapped potential in relationality.

That, for me, is the real hope.

Javier Rizo: I hear you that relationality is central to this vision of a more egalitarian society. But I can’t help thinking about the challenges of doing this kind of relational work, especially when people have deep material and ideological investments in undermining others’ well-being for their own gain. This happens in so many areas—take climate change, for example. How do we motivate people to engage in dialogue when there’s such a vested interest in not having that dialogue? How do we even get people to that point?

Mick Cooper: A colleague of mine, Kirk Schneider, who works in the existential-humanistic field in the U.S., has been developing these kinds of dialogues—bringing together people from very different positions to actually talk to each other. I think that kind of work is really important.

But how do you do it? I think one major reason people avoid dialogue is that they don’t believe they’ll be truly heard. They anticipate being shamed, dismissed, or disrespected. If, from a progressive standpoint, we can embody a more empathic stance—conveying a genuine willingness to listen—it might encourage more people to engage.

I completely understand that some perspectives are deeply offensive, and that there are times when people don’t want to hear them. But at the same time, responses like cancel culture, however understandable, can push people into a defensive stance where they feel there’s no space for conversation. And when people feel shut out of dialogue, they’re even less likely to listen.

At the end of the day—and this might be a controversial thing to say—the Musks and the Trumps of the world, however horrifying their behaviors may be, are still human beings. They have needs for connection, for self-esteem, for material security—but also for being heard. That doesn’t excuse their actions, but it does mean that if progressives want to lead change, we need to think about how to create a culture where even people like them might feel there’s space to engage, rather than feeling they’ll be instantly condemned.

Public discourse, especially on platforms like Twitter/X, is so steeped in shame and antagonism. And shame pushes people apart. The more people feel shamed, the more they dig in, the less they listen.

Of course, none of this is easy, and I wish there were a simple solution. I feel desperate for one, especially given how urgent these issues are. Climate change, for instance—the latest data on rising global temperatures is absolutely terrifying. The urgency is real. But if that urgency fuels even more blame, criticism, and division, I worry that it will only be counterproductive.

That doesn’t mean there shouldn’t be clear boundaries, clear demands, and clear expectations. But I think these need to exist alongside a broader cultural shift—one that fosters empathy, understanding, and a willingness to engage. If we want to create a compassionate world, we can’t do it through means that are unempathetic or unkind. That only breeds more discord, more antagonism. If the goal is a more cooperative, compassionate world, then the path we take to get there has to reflect those values as well.

Javier Rizo: I’m thinking about what you’re saying in terms of changing the nature of political discourse. Do you have a sense of the social conditions necessary to actually get people to that point? There’s so much conflict—especially in contexts like class struggle, where labor unions are in direct confrontation with employers. How do you get people in power to even want to come to the table in the first place? Where does your vision fit within the present and the future?

Mick Cooper: It really is difficult. I think part of the way in is engaging with that fear. In conflicts where mediation has worked—like in Northern Ireland—it wasn’t just about military solutions. It was about bringing people together to talk about their needs, to articulate what their communities want, and to find solutions that meet the needs of both groups. If people believe there’s no chance they’ll be heard, they’re less likely to engage in dialogue at all.

Political strategies and pressures are absolutely necessary—many people are working on that front. But alongside those efforts, if we can also create ways for people to listen to one another and develop deeper mutual understanding, then over time, we may be able to foster a culture where these kinds of conflicts become less frequent and less intractable.

Javier Rizo: Yeah, the hope is to instill these values—really inviting the other in, really trying to understand. It’s clear to me how psychotherapy embodies that in practice, and I hope more people can engage with these principles, whether by experiencing them in their own therapy or carrying them into their lives. And for therapists, maybe that means becoming more engaged in social work.

I really want to thank you for taking the time to talk with me today and for sharing your thoughts on connecting psychotherapy and social justice. For those who are interested—whether they’re therapists, clients, or just people curious about these ideas—what are some ways they can engage more with your work?

Mick Cooper: Thanks, Javier. Well, there’s the Therapy and Social Change Network (TaSC)—we hold seminars and discussions, and we have links with similar work in the U.S. I’d really encourage people to look at the multicultural and social justice competencies developed in the States, which have been a major effort to integrate social justice concerns into therapy. Of course, there’s also Mad in America and other organizations that raise important questions about power structures in psychiatry—those are great starting points for exploring these issues.

Another important figure is Michael Lerner in the U.S., who, like me, has been thinking about radical acceptance in politics. In the UK, we’re seeing more groups emerging and more people engaging in these conversations, though it’s still in very early stages.

Some of the questions you’re asking—like how to bring people in power to the table—really highlight how much work remains to be done. The honest truth is, I wish I had a better answer. But I think part of building a more emotionally literate politics means being able to acknowledge when we don’t have easy answers. Instead of pretending certainty, we need spaces to think together about how to move forward.

Right now, we’re not at the stage where there are well-established groups with clear agendas on these questions—we’re still in the formative phases. I wish we were further along, but the reality is, we can’t rush it. A culture of radical acceptance won’t emerge through force, self-criticism, or frustration that things aren’t moving fast enough. It’s just like in therapy—self-acceptance doesn’t come by beating yourself into it. It often happens slowly, in layers, in waves. And sometimes the first step is accepting that you don’t accept yourself yet.

The same applies to this broader movement. We’re at the beginning stages, and that’s okay. I’d really encourage people to visit the TaSC website, see what’s happening, and consider getting involved. We desperately need more people stepping into leadership roles, engaging with these questions, and bringing psychological insights into the larger social justice conversation.

**

As a survivor of psychotherapeutic abuse and malpractice of conservative and “progressive” professionals alike I have come to the conclusion that “progressive” psychologists and psychiatrists like Mick Cooper suffer from a behaviour pattern that is known in individual popular psychology as the battered wife syndrome.

This is a label for the phenomenon that folks who are being abused by a loved one don’t manage to accept the cruel and aggressive disposition of their abuser and leave. But instead go back and try to help the abuser better themselves again and again.

A strategy that is understandable because it allows the victims to not feel the pain and realise the losses in the wake of the horrific abuse they have experienced. But also a strategy in which these folks get stuck and is technically a dead end because only an abuser is responsible for his violent behaviour and only they can decide to stop their abusive patterns and change.

Historically psychiatry’s rise into the power center of the “bourgeois” modern world came with the rise of the medical field at large into a part of the ruling class and the new order. What “progressives” are trying is to undo being part of the ruling class without giving up their privileges that come from being a part of the ruling class. This endeavour is hopeless, it has been tried for decades and it has brought nothing but failure after failure. All the while horrifc abuse in any branch of psychotherapy and psychiatry went on and was never adressed.

The good news is that unlike these “progressive” mental health professionals in their trauma bond with psychiatry/clinical psychology people with serious challenges to their mental health don’t need psychiatry and psychotherapy to be reformed. What they need are alternatives that have no ties at all with these fields. Fields that have proved themselves not only a total failure to help people with their challenges but also with a more than 200 years old unacknowleged history of horrific abuse of their patients/clients.

These alternatives exist already. And as soon as one gains insight into the reality described above, lets go of the hope to find support within the psychiatric field, and allows the pain in, the alternatives that are individually suitable start to jump right into your face one after another.

Psychotherapists need clients – but nobody needs a therapist. Trust the process.

Report comment

“What “progressives” are trying is to undo being part of the ruling class without giving up their privileges that come with being part of the ruling class.”

Thank you for highlighting the hypocrisy of this approach.

Report comment

“Psychotherapists need clients – but nobody needs a therapist.”

BEST COMMENT EVER!!!

Report comment

Lina, thank you for mentioning the way the dynamics in so-called “therapeutic” relationships resemble those in the battered wife syndrome.

It helps me understand why I kept going back, despite my deeply felt misgivings about a system I had always been quite leery of.

It’s disturbing how modern culture grooms people to depend on those trained to take advantage of them, especially in matters of so-called “mental health”.

I’m not sure why, but something tells me that power and pain will always be the elephants in the room….

Report comment

My pleasure, Birdsong.

Unfortunately, I have so much experience of being harmed and violated in psychotherapy that I became a master at understanding all aspects of it.

I was able to understand that I had been continously harmed in several psychotherapeutic settings since I was ten years old because the therapists became more aggressive the better I was doing thanks to alternatives like yoga, meditation, and self-help groups. Resources that I had opened up for myself.

I then tried to teach them what I had found out what really works for me to get better and didn’t realise for a long time that they didn’t want to know and couldn’t. I am glad I was able to then see the corruption of the psy field and just walk away.

The personal stories that I have read here on MiA from people with similar experiences were extremely helpful and I don’t know whether I would have managed to escape the field without that resource.

Then the above mentioned pain set in. Over the next one or two years when coming to terms with the decades of psychotherpeutic abuse that I had experienced I almost lost my mind. But I soon understood that every wave of pain wasn’t as intense as the one before and that my mental health was slowly recovering.

It is now five years in July that I was able to escape this cult like system of abuse and I am of course not fully over it. Sometimes I am afraid I’ll never be but then I see that I am making progress everyday and I am satisfied.

I am able to sit on longer and longer silent mindfulness retreats and just sit through the pain of these experiences one tiny bit at a time. I have great teachers who have dealt with similarly painful liberatory processes and who have therefore tought me how to do it. The key is to go slowly.

When I asked myself why my former therapists were not able themselves to leave such a corrupt field of work behind them and how they were able of harming their clients without noticing it, I realised that for them similar processes are going on.

I learned that it is normal that young psychotherapists are harmed and abused in their training psychotherapies themselves (Someone has put that fact up on Wikipedia. Thanks! That was helpful) Thus, they are themselves stuck in a trauma bond with their therapists and the oppression at the heart of the field.

Report comment

Lina, it’s wonderful you found such helpful alternatives to psychotherapy. I know how hard and scary it is to walk away from the mental health system. It’s one heck of a journey to embark on alone.

I’m uncomfortably familiar with the unpleasant reactions you received after informing your psychotherapist(s) of things that worked better for you. The unfavorable responses you faced are ones I’m familiar with.

I’ll never forget the time I was “in session” with a psychiatrist who became enraged when I finally got up the courage to tell him that I got more out of chatting with random people at the Costco across the street from his office than I did sitting across from him in what was essentially a staged encounter. And I was pleasant about, it too! It felt great to sit up and finally say what I felt was true for me. You’d think he would have been happy for me.

Most of the psychotherapists I’ve seen weren’t much better at concealing their anger when faced with what seemed for them to be an almost existential threat. It was obvious they found my matter-of-fact truthfulness threatening to their sense of who they thought they were.

For most people I’d chalk up such defensiveness to them simply taking things too personally, but not in these situations as I’m pretty sure most of these people find refuge in being chronically dissociated, or, as you so aptly put it, “…they are themselves stuck in a trauma bond with their therapists and the oppression at the heart of the field.”

Report comment

Thanks, Birdsong. Yes, it was truly hard and scary to walk away. Especially, because I didn’t know whether it would work out.

At the same time the decision was easy. I knew I’d rather not make it being independent of psychotherapy than allow the abuse and malpractice to go on and becoming a broken person who watches herself with the eyes of their deluded psychotherapist.

In those years I chatted with several long time users of psychiatry who had experiences with psychosis in a self-help-group where I went to find help how to deal with my dissocial and delusional and highly abusive mother.

I found that they had adopted just such perspectives on themselves and had given up themselves. They got extremely aggressive against me when I tried to find help among them about how to adress the abuse and harm that I was experiencing whether it was from the side of my mother, a psychiatrist, and the rest of my family, or from the side of my psychotherapists.

I think that these discussions were crucial for me to understand that psychiatric abuse instilled in patients (and “progressive” clinicians alike) something very similar to the battered wife syndrome.

I am glad you were able to walk away too!

Report comment

Lina, I’m sorry you didn’t find fellowship or at least a modicum of caring and kindness from the self-help group. It’s unfortunate the way so many people internalize some version of psychiatry’s “broken brain” narrative. I try to understand their seeming willingness to so easily forfeit their agency. Then I remember how easy it is to fall into psychiatry’s medicalized rabbit hole. It seems most people would rather do that than explore the things that most likely had a hand in shaping how they feel and react to the world.

I believe everyone should be free to choose their own way of dealing with things — as long as they know there’s more to “mental health” than psychiatry’s doomsday narrative.

But most of all, I applaud your perseverance in finding what works best for you.

Report comment

I am having a hard time reading this discussion. Well of course Carl Roger’s, and also Rollo May and other white males And the old word was eclectic not pluralistic.I thought DBT was an awful reaction to Dr . Linahen’s own life and career.

This is not new thinking is using a different vocabulary for the same old same old. In the Roman Catholic framework one of the wisest sayings and begun as a joke is that the grace from the liturgy was lost as soon as people left and got in their cars and tried to get out of the parking lot first.

Trauma along with no vertical thinking and creative thinking is lost in the time either before or after the old one hour therapy.

Complex human problems need the acknowledgement of complex solutions requiring new frameworks and frameworks. Flashbacks are not linear. One can get one in the mall when a song is played on the PA system. One can be back in time because of a certain scent or smell.

All the human senses and other forms of sensation are in a complex card or chess game within one human. I would think this is also part with the other species on this planet and possibly the earth itself.

I appreciate the effort but let’s be real here when one defends oneself with but my parents were open minded thinker the dice has been put in play.

We need to open ourselves to the vast beautiful and oh so complicated and complex number of worlds we live and walk through every day. Human civilization deep deep diversity and at the same time deep deep similarity.

Charles Kingsley an old Victorian wrote several books for children. He was very anti Irish in ways and isms but he did try and in The Waterbabies he has a paragraph on the importance of adults admitting to children they do not know. In At the Back of the North Wind he highlights a young boy’s short life lived in poverty. In his Princess and Curdie books he highlights mines and enchantments and hope.

Only one small not well known human. If he created these universes what can we do to create universes of healing? The old trope of beginners mind might help.

Report comment

“Complex human problems need the acknowledgement of complex solutions requiring new frameworks and frameworks.”

Take heart. This may seem like the truth, but it is not.

It’s just what we’ve been led to believe by THE VERY PEOPLE who have A VESTED INTEREST in keeping it the “mental health” racket going.

It’s like being in a relationship with someone who keeps confusing you, and then keeps you thinking solutions are impossibly complex, when all you really need is an awareness of what’s TRULY going on.

In this way, politics IS personal.

Report comment

The best solutions make things feel simpler, not more complex. One of the sure signs that the DSM is off base is the ever-increasing complexity of the system over time. Not to mention the ever-increasing numbers of “mentally ill” according to this system.

Report comment

I think you have to like creating confusion to work in “mental health”.

Report comment

I don’t agree. I think the system is organized to create confusion, and a lot of folks are simply confused. There are a small but powerful number who DO enjoy creating confusion – otherwise known as “narcissists” in their own parlance. These folks are in charge of the big decisions (opinion leaders) and support and create the system as it is. They are the ones who put out the propaganda and attack those who dare to challenge the “status quo.” Such people do absolutely exist at the lower levels of organization (the system itself attracts such people), but there are plenty who want to do the right thing and are simply confused by the propaganda and peer pressure within these organizations. There are also rebels “behind enemy lines” who do really good work and deserve credit for doing so despite the pressures and discrimination they face.

It is simplistic to assume ALL “mental health” workers have anything in common. It is absolutely not supportable to assume that creating confusion is a goal of all or even most “mental health” workers. I think most of them are more confused than we are!

Report comment

Thank you very much for unconfusing me, Steve.

I think what I was trying to say is this: to me it seems you’d have to like being confused in order to work in a system built on confusion, because if you don’t, you’d probably go insane. I know I would.

That being said, I’ve been shown no reason to doubt that most “mental health” workers are more confused than we are.

Report comment

I am talking from experience here. I was inside the system with a totally different philosophy than those who were running the show. I was not confused particularly, but I was certainly disheartened by the kind of pressure and discrimination I experienced when I failed to “get with the program.” A lot of it was simply isolation – folks were “He’s an anti-med guy” and ignored many of my comments and observations. I was able to fight for clients in specific situations and provide something that others did not, but it was pretty exhausting. At a certain point, I realized I was supporting an oppressive system by even participating, even if I was doing some effective damage control, and decided I had to get out of there. But I would not say I was confused. Just annoyed, disheartened and infuriated!

Report comment

Clarification: to me it seems you’d have to have a high tolerance for confusion in order to work in a system built on confusion, because if you didn’t, you’d probably go insane.

Report comment

Steve, I’m sorry I sounded so disparaging. My fury at how things are run in the mental health system just gets to me sometimes.

Thank you for doing what you did for as long as you did. I can only imagine how horrible it must have been having to function in such an invalidating environment.

Report comment

I felt I was doing good things. When the bad outweighed the good, I had to stop. But I really respect those who are in the trenches or behind “enemy lines” because people need help NOW and it’s the only way I know those in the system can get support.

Report comment

I’m sure you were doing wonderful things. I have great respect for those who are in the trenches or “behind enemy lines”. I just wish there were more people dedicated to changing things.

Report comment

Me, too!

Report comment

🙂

Report comment

Really good. “Of course, therapy alone isn’t enough. Economic and political changes are also crucial.” Crucial. These are huge, pervasive systems in need of fundamental change (or replacement), but it’s nevertheless crucial that they fundamentally change (or get replaced). Otherwise, we can expect more of the same.

Report comment

Last night I watched the movie Don’t Look Up. It’s about an impending asteroid collision with Planet Earth. It stars Leonardo Di Caprio. Mark Rylance acts in the film also. High Strangeness Experiences is a term often coined in Extra Terrestrial Literature. I like it. It allows for the peculiar, ineffable, weird, exotic, synchronistic, bizarre, other worldy experiences to have a grain of possible truth. I could fill a book with my own High Strangeness Experiences. I used to feel satisfied that I was channelling the spirits of poets. My writing improved fantastically. I even won a prestigious literary award. I was certain I was being guided by Shakespeare, amongst others. I still believe this. I don’t even like Shakespeare. I’ve never read his opus. But maybe he liked me. Stranger things have happened. His ghost. Occasionally I spectate some thespian video related to Shakespeare. Recently Mark Rylance was acting in a drama Wolf Hall, or it’s sequel. I felt like sending that actor a postcard mentioning how I knew Shakespeares ghost personally. I felt sure that ghost will have been aware of Mr Rylance’s epic acting in The Royal Shakespeare Company. This is where Mark and me might have both had High Strangeness Experiences. A gusty candle, a flapping curtain, a floating page, a runnel of wet ink.

Two decades ago I was given a message from the beyond that Holy Wrath was coming because humanity could not stop polluting the planet. I understood it to be coming in various forms. One of those involved five meteors, small ones, hitting the ocean and causing tsunamis. I object to the notion of Holiness and Wrath, so I flung those words out and now see cosmic events as just being random, not pitiless punishments. Most planets are polluted by stuff that makes them uninhabitable. I have nevertheless carried the five meteors prophecy for two decades, long before the film Don’t Look Up was begun. Before the pandemic, I had to use up spare money by staying at a very wealthy hotel for a night. My schizophrenia was terrible but I arrived on time to find the hotel deserted. My focus rapidly attended to how preposterous my dowdy clothes were for an expensive hotel. I became obsessed with trying to mimic posh people as I didn’t want the guarded butlers to spot my schizophrenic humble dishevelled inner self and throw me out. A comedy of errors ensued. It was not until the breakfast in the opulent dining room that I realised why the hotel was so empty. It was full of massive security police protecting Leonardo Di Caprio, who had the hotel more or less to himself, minus the mad lady in bedroom nearby, myself. I believe that my own handlers in the spirit realm, my own protection detail, will have floated through to that movie star’s bed chamber and whispered into his ear about five meteors coming, small ones, to which he might like to make a blockbuster about a great big meteor in future, to help people get used to the possibility of such a random event. Calm them all, so to speak. Was I guided to be in that place and time, in that hotel, by my spirit folk? How odd is it that two meteor buffs would share a hotel? As for Shakespearean Mark Rylance being in the same movie…

High Strangeness Experiences seldom get a lookin in mainstream psychology or therapy. Gestalt Therapy is very open to the reality of intuition. A phrase in this article says “how to relate to others”. I find it a bit odd. If we accept we may never truly know an individual, as if they are a golden being unknowable, then we must ask them to reveal themselves as if they are the only authority on themselves. Until they do so we cannot possibly “relate” to them. Not unless we are bullying them with our own judgement of them. If we can accept “High Strangeness Experiences” maybe we can let people stay Highly Strange in a beautiful way.

Report comment

Politics in therapy is a terrible idea when therapists already have too much power.

Report comment

As a contributor to MIA, thank you for your balanced perspective on the best and worst of mental health care. I have been a mental therapist for more than fifty years. No one is without fault, nor is anyone perfect. If there will be a positive social change, it must come from respectful, constructive dialogue between practitioners, journalists, and mental health critics. Otherwise, we are all in trouble. We live in an age of intensifying groupthink, permeating all societal sectors. My views have changed since I recently published two articles in MIA. I hope we can all keep an open mind. The world depends on it.

Report comment

Generally speaking, among the MOST CLOSED-MINDED people I’ve met, are psychiatrists, psychologists, and “therapists” of all kinds….it wasn’t until I ditched the so-called “mental health” folks, that my healing truly began….. What’s the point of a “good” therapist, in a BAD, BAD, BAD profession?….

Report comment

“If there will be a positive social change, it must come from respectful, constructive dialogue between practitioners, journalists and mental health critics. Otherwise, we’re all in trouble.”

WTF??? We’re already in more than enough trouble thanks to the groupthink of most practitioners, journalists and so-called “mental health critics”.

And btw, what’s wrong with taking seriously the many personal stories RIGHT HERE ON MIA?

Report comment

I and many others do take very seriously the many personal stories RIGHT HERE ON MIA? GIVE OTHERS A CHANCE TO UNDERSTAND YOUR DILEMMA WITHOUT HYPERBOLE.

Report comment

What’s wrong with hyperbole?

Report comment

Hyperbole means exaggeration to the point of meaninglessness.

Report comment

It’s pretty hard to exaggerate the harms committed by the so-called “mental health” industry.

Report comment

Thanks, Birdsong. I find your comment and some of the other responses to this interview reassuring.

The suggestion that wider engagement and reform within systems of power and with the individuals who serve these systems as being not only possible but welcomed seems naive at best and would leave already vulnerable populations open to further injury and exploitation. That’s why criticisms like these are relevant.

Group-think is about assimilation, with its goal being the annihilation of self, conscious independent thought, critical thinking and a deadening of empathy for every other human being on the planet.

While a human-centered approach sounds good in theory (and I don’t disagree), in practice it’s not as if “the horrifying behaviors” referred to during the interview are limited to specific individuals or members of a particular political party or group.

Instead, it’s about systems of power and the decisions being made by people in power about other human beings whose lives are as valuable as any other and yet suffer without having had a voice in the decisions being made about their lives. This includes literally billions of people in ‘other’ parts of the world as well.

In an ideal world, a genuinely person-centered approach would be two individuals, or possibly a *small* group of individuals, voluntarily coming together without any hidden agendas or power imbalances existing between them and making decisions that affect their *own* lives, without causing unnecessary harm or dehumanizing anyone.

Every truth-seeking philosophical, religious, spiritual, and intellectual perspective worthy of serious consideration has, in some way, made similar points about the corrupting influence of groups, systems and institutions of power. Reality isn’t hyperbole.

To engage meaningfully includes being able to peacefully disagree and thoughtfully challenge faulty assumptions about the world we live in . . . without creating new power imbalances or resorting to violence.

“There is a view of life which holds that where the crowd is, the truth is also, that it is a need in truth itself, that it must have the crowd on its side. There is another view of life; which holds that wherever the crowd is, there is untruth, so that, for a moment to carry the matter out to its farthest conclusion, even if every individual possessed the truth in private, yet if they came together into a crowd (so that “the crowd” received any decisive, voting, noisy, audible importance), untruth would at once be let in.

“For “the crowd” is untruth.” ~ Soren Kieerkegard

None of this is intended to dehumanize *anyone*.

Report comment

Thank you, Tree and Fruit. I find your comments truly compelling.

I also think trying to change the mental health system is naive for all the reasons you so eloquently stated.

P.S. Thank you for saying that reality is not hyperbole.

Report comment

“P.S. Thank you for saying that reality is not hyperbole.”

You’re welcome, Birdsong.

I was also thinking how irony, cynicism or even sarcasm can be ways for us to express our frustration, with the last option admittedly not always being the best or ideal way to communicate.

I grew up in the ‘hood’, so every once in a while, as a counterreaction to some extreme situation, I privately do this, always separating message from messenger and without wishing anyone harm.

It has a clarifying effect and immediately helps me to cut through all the gaslighting and subterfuge and stay sane in an insane world. It’s a part of who I am.

Since I haven’t yet figured out how to consistently reply to specific comments that don’t have “Reply” as an option without interrupting the continuity of the thread, I want to share a synchronicity with you related to one of your and Nick’s recent exchanges.

I woke up this morning thinking of a favorite quote:

“That of which we cannot speak, we must pass over in silence” ~ Ludwig Wittgenstein

One of my favorite books (and I have a lot of favorite books) is “Wittgenstein” by H.L. Finch, an author who has a beautiful way of simplifying complex thoughts.

There’s a video on Wittgenstein I like too:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XcF-XoF2HFc

Life is symbolic. Language relies on symbols that can be easily manipulated to convey meanings absent of Truth.

Without casting any stones, in the past I’ve sometimes been guilty of this too.

Report comment

I think it’s always worthwhile for professionals and patient advocates to personally engage with and sometimes challenge individual therapists, doctors, nurses, aides and other caregivers who work within these systems.

Years ago, I would sometimes write letters to the State documenting specific issues related to improper record-keeping, unlawful increases in monthly fees, intentional over-medication and other issues, always working closely with our local Ombudsman.

All of my complaints were investigated and found to be justified.

In the end, and though the facility was fined for their violations, and certain procedures were put into place, I realized it hadn’t made much of a difference and may have done more harm than good.

So as far as appealing to people in positions of power to address systemic issues in a meaningful way, I’m doubtful.

Training is necessary and important, but what happens after training when no one is looking?

In the end, it will always come down to individual choices and caring and paying attention to what’s going on with other individuals and all around us and in all of the hidden places.

There are things that can’t be taught or externally imposed or impressed upon someone.

To be fair, it was mostly about the owners rather than the caregivers who were, for the most part, very conscientious. But not all of them.

A single individual can still do great harm.

Report comment

“There are things that can’t be taught or externally imposed or impressed on someone.”

That’s why I think seeking professional has the potential of ending up counterproductive.

There’s great harm in encouraging people to think that having a degree means someone knows what they’re doing.

The exchange of money just adds more “political” chaos to an already imbalanced relationship.

When all is said and done, how can you trust people trained to keep their true feelings and identity a secret?

Report comment

Correction: That’s why I think seeking professional help has the potential of ending up counterproductive.

Report comment

I agree. A degree isn’t a guarantee. Individuals with an online presence sometimes make themselves known through social media, if we know what to look for.

As far as seeking professional help, I’ve found the exceptions prove the rule.

The director of our local Ombudsman was as discouraged and frustrated as I was with the system and its professional caregivers. He was a good guy who was underpaid, overworked and dependent upon a small group of older volunteers (ombudsman) to be his eyes and ears and legs. He took my calls even after my mother died and wanted to personally intervene to help me get back some money we were owed.

I already mentioned he offered me a paying job, which surprised me considering his budget and my lack of ‘qualifications’. I think he recognized a kindred spirit in me and knew I was motivated by wanting to do right by people who were without power or a voice, seeing as how I’d also advocated on behalf of other residents over the years.

Something I probably mentioned in another comment was that my husband and I lived within walking distance of the board and care I found for my mother, so I was able to visit her every day, sometimes several times a day and occasionally at night, when she needed extra reassurance.

My husband took care of her too and was a regular visitor. He did a lot of her shopping; there were so many things we had to take care of and pay for out of pocket that weren’t covered by her rent. It was a lucrative business.

Report comment

John McKnight’s “The Careless Society: Community and Its Counterfeits” reviews some of the history of marketized relations, including the medical industry, supplanting autonomous social relations among people who become subject to professional monopolies of knowledge as power. The ultimate goal of capital is to commodify, and control, all life.

Science in general doesn’t exist in a vacuum value-free of ruling power. In modern mythology of enlightenment and progress, science serves as the opiate of the masses, beyond religious ideology. So called human sciences like psychology serve to socially engineer subject populations into compliance with the death march of ‘civilization’ under class rule. Myths of mental illness manage us for population control within generalized conditions of abuse and trauma, which remain obscured under rule by experts treating individualized ‘cases’ and ‘patients’ uprooted from communal traditions providing any alternative to the enforced social system.

Even the human-centered theory and practice of Carl Rogers is fair game for insidious methods of mind control to manufacture consent and thus pervert its healing potential. (And when you next hear warning of drinking the kool-aid, remember that Jonestown’s victims were killed, ‘suicided’, shot by bullets or with posionous injections, to cover up ‘cult’ links to the CIA’s MK-Ultra program.)

The most liberating and egalitarian option is to deinstitutionalize and decentralize the knowledge-power apparatuses of rule, and restore people’s power to form our own more human alternatives of care and compassion, in communities that live and learn and love far beyond the machinery of production and profit under which we suffer. Accordingly, a primary purpose of any professional dissenting to the managerial role s/he plays in the present relations of power over us is to abolish the basis for the existence of her/his own caste.

Report comment

Has Mick Cooper (or Javier Rizo for that matter) looked at Deleuze & Guattari work? Although written in the 1970s (and it shows), they are now coming into focus in addressing politics in psychotherapy. Their books on capitalism and schizophrenia go the heart of what’s wrong in the world. However their writing is so difficult to understand and what we now need is a group of scholars able to translate their work.

Now that cognitive science is entertaining the notion that we have “extended minds” (or “extensive minds”) (e.g. I feel my wheels on the road when driving (i.e. I am one with the car when driving), or that you miss seeing the guy dressed in a gorilla suit who walks into the middle of the scene, when you are busy counting the number of time the players pass the ball); it is inviting us to see we are not “independent minds” (or brains) encased in skulls, but “extensive” identities.

D&G talk about “Bodies without Organs” which is their way of talking about what is commonly called being in the “flow”, which is to be encouraged as it is a way of resisting the excesses of capitalist culture which is now out of control, and destroying the future for everyone. Having an extensive mind you become more aware of how capitalistic culture is disciplining you (a la Foucault) and/or corrupting you.

Report comment

I think what you describe boils down to gaining perspective on how much the immediate environment affects (or not) an individual.

Report comment

…in other words, it’s a matter of stepping back to get some perspective on how your surroundings may be influencing your state of mind.

Report comment

I checked out your website, Nick. In addition to a Wittgenstein synchronicity (which I mentioned to Birdsong in a comment I left earlier today), I discovered another interesting coincidence.

Last year, and before I discovered this site, as I was waking up I ‘dreamed’ the following message:

“No as the gift is nous” . . . or was it “Nous as the gift is no” . . . I couldn’t remember exactly, maybe it was both.

I assumed it had something to do with choice and the importance of exercising greater discernment and self-agency in choosing to say no to wrong things. After reading on your website what you’d written about negation/apophatic theology, I recognized another layer of meaning, one that seems to support my original understanding.

I’d been thinking about a choice I made decades ago, when I was much younger, and how confused and naive I’d been. It was the first time I ever remembered feeling spiritually connected to someone in a way I’d never felt before. In retrospect, and because it transcended anything I’d ever experienced, it was my first real EXPERIENCE of God’s loving presence in my life and what was possible between human beings once we understand how connected we are to one another.

Meister Eckhart spoke about this same connection between romantic and divine love.

I imagined the relationship to be something that it wasn’t, and yet this negation and disillusionment provided an opening. Good things came of it, in spite of my mistake and probably because of it.

Report comment

Talk about undue influence…

Navigating therapists’ inclination for bias is difficult enough without having to worry about them inadvertently(?) looking to saddle you with their own political agenda.

And don’t think for a moment that only a few would give it a try…

Report comment

Have you heard the saying that the “political is the personal” – in other words therapists are political now – but what would you prefer a therapist who denies their politics or one that acknowledges them and is transparent about them?

Report comment

I’d prefer never to see a therapist of any kind.

Report comment

…and as a therapist I prefer not to see anyone who doesn’t want to see me.

Report comment

My goodness, that’s generous of you!

Report comment

Why is that generous Birdsong, or are you being sarcastic? If so, why??

Report comment

I’m sure you’re capable of answering those questions yourself.

Report comment

Birdsong, did I do something to offend you, is that why you are being sarcastic? If so I apologise. But what did I write specifically that offended you?

Report comment

Nick, while it’s true that “politics is personal”, it’s highly unethical for therapists to use therapy as a place to air their own political views – asked for or not.

It’s for a client’s advantage for therapists to keep in mind that psychotherapy is primarily designed to assist people in various states of emotional distress and confusion – an unusual arrangement that can and does set the stage for the person with more power (in this case the therapist) to strongly influence vulnerable people needing a sympathetic ear.

This creates fertile ground for therapists to take advantage of susceptible people already unsure of themselves no matter how ethical or conscientious the therapist.

Report comment

…all the more reason for therapists to behave responsibly.

IMHO.

Report comment

Hi Birdsong

I will provide some examples – take narrative therapy and anorexia nervosa – the narrative therapists are attracted to ‘externalising’ anorexia as a discourse rooted in the patriarchy, and following Johnella Bird might ask,”what kind of relationship do you want with the patriarchy” (this is called ‘relational externalising’). Somewhat similarly some psychoanalysts these days are attracted to the idea that the ‘unconscious’ is more the social environment rather than a repository of conflicts as Freud proposed. Erich Fromm published in 1955 ‘The Sane Society’ saying society is obviously “mad” as evidenced by its propensity to have wars on a regular basis. Fromm was critical, similarly to Foucault, of our idea of “normalcy” – it is a distorted mirror that most look at themselves with.

I think it is unethical for therapists not to look at what’s called the “social unconscious” as it is that which is at the root of our psychoses and neuroses – otherwise they can be accused of supporting capitalism or the “craziness” that is driving the misery.

Report comment

Nick, you bring up some very good examples regarding the “social unconscious”.

With that stated, I still think it imperative for therapists to let clients lead the dialogue, especially these days when words like “capitalism” and “patriarchy” are so politically charged, meaning therapists ought to respond to people’s psychological dilemmas in ways that help lead them to discover their own attitudes, beliefs, views, and feelings, etc., not the therapists.

Report comment

Yes – that is why I mentioned Johnella Bird’s ‘relational externalising’ – which asks the question “what kind of relationship do you want with [say] patriarchy?” – which has more of a Levinasian ethic to it [Levinas was a philosopher who claimed that ethics comes first – and in this case the client leads the discussion].

Report comment

Thanks. Sounds like useful and interesting stuff….

Report comment

Nick, I tend to look at things more socially/culturally than politically, especially when I’m considering psychological things, although I wouldn’t deny that these are inextricably intertwined.

Report comment

Nick, I just read a bit about Emmanuel Levinas and am pleasantly surprised because to me ethical responsibility is a pretty big deal.

His “Ethics as First Philosophy” makes him sound as though he might be a philosopher I could actually respect.

Report comment

Hi Birdsong

Yes Levinas is cool in my books. He approvingly quotes Dostoevsky’s Father Zossima (in The Brothers Karamazov) who says “everyone of us is responsible for everyone else in every way, and I most of all”. (“I most of all” because in recognising one’s responsibilities to others it puts even more stress on oneself) Wittgenstein also approved of that quote. Levinas says we have an infinite responsibleness for every person, only limited by our responsibility for others. So only my responsibility to others limits my responsibleness to you.

Report comment

Levinas’s thoughts on infinite responsibility remind me of Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount (love your enemies, do unto others as you would have them do unto you) and his parable of the Good Samaritan (love your neighbor as yourself).

Wittgenstein’s thoughts on how language is used makes me wonder what he would have to say about psychiatry’s “DSM”.

Report comment

I’ve published papers on Wittgenstein and mental health.

Report comment

Nick, I looked up and found two articles written by you. One is called “Wittgenstein and the Red Queen: Attuning to the World and Each Other”, and the second is called “Wittgenstein and the Tikanga of Psychotherapy”. I was surprised to find them both readable and engaging. I look forward to finishing both!

Report comment

Hi Birdsong – there is lots more if you put in google “academia.edu + Nick Drury”…..

Report comment

Nick, thanks for letting me know! 🙂

Report comment

You seem to be pushing politics in the therapy space, something I consider not only untherapeutic but also highly unprofessional.

Report comment

Hi Birdsong,

It seems that you are making the mental health field into a political issue. The anti-psychiatry movement has been going on for a long time. Serious dialogue is still needed. I don’t think this is unprofessional, unethical, or unprofessional. Correct me with a reasoned argument if I’m wrong. I do think it is irresponsible and tragic that many suffering people will follow your advice and not seek out therapeutic help when needed. I am glad I sought out my beloved therapist after my suicide attempt. Your response to that article in MIA was to claim, without foundation, that there is no such thing as a excellent therapist, only excellent human beings. I invite Nick Drury and others to review my previous articles published in MIA. Peace,

Report comment

Michael, I’m delighted you found the help you needed when you needed it.

Nevertheless, I think express myself reasonably enough; if what I say sounds political to you, so be it.

I also think people are intelligent enough to decide for themselves whether or not to seek professional help.

Report comment

Michael, there is such a thing as irreverent humor.

Report comment

I am sorry Michael I haven’t time to delve into the MiA archives to find your previous comments – but I will keep an eye out for your subsequent postings. And like Birdsong, I’m delighted you found the help you needed when you needed it.

Report comment

Birdsong, I am well aware of irreverent humor. This is also called disingenuous.

Report comment

Perhaps you should cultivate humor of some kind.

Report comment

This comment isn’t directed at you, Nick, or anyone in particular, but I would like to add my own thoughts and feelings about the intersection of politics and therapy, in that they probably differ from others who’ve commented.

The influences that have most affected my mental health, and that have sometimes left me feeling hopeless and despairing, are both personal and impersonal and can’t really be separated.

It’s lonely and frustrating to live in a world where instead of truth-seeking most of us have been conditioned to seek out information that confirms our natural biases and beliefs and to (consciously or unconsciously) make choices that seem to offer us the greatest potential benefit without considering those who would suffer unjustified harm and sometimes death.

Most people take for granted that I’m as excited as they are about participating in a political system where, as they see it, we’re still given the option of ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ choices… when for me, a vote would only legitimize the system itself and make me complicit in causing more harm than I already am.

On the other hand, I understand why people living on the edge and in desperate situations or in smaller communities, sometimes vote based on specific issues that affect their wellbeing and survival, and for candidates who promise to address these issues.

If I were to see a therapist (which I won’t), how could I share any of this, since more likely than not they’d hold a particular political position very different from mine and be influenced by an intellectual and ethical perspective I find not only alienating but condescending.

A friend, after one of our long discussions, shared my perspective with her Buddhist therapist, with “Right Action” (that causes no harm) being part of the Noble Eightfold Path.

She said her therapist quickly dismissed my perspective as being influenced by propaganda.

I’m not singling out Buddhism, btw. My friend’s therapist could just as easily have been a Catholic or Presbyterian or even a Quaker, Socialist or Communist. To each their own.

Report comment

“The influences that have most affected my mental health, and that have sometimes left me feeling hopeless and despairing, are both personal and impersonal and can’t really be separated.”

Tree and Fruit, for what it’s worth, my thoughts and feelings align with yours 100%.

Report comment

It’s worth a lot. Thanks, Birdsong.

Report comment

🙂

Report comment

It wouldn’t matter if my therapist shared their political views with me or not.

The kind of support they’d be able to provide would still most likely be influenced by their conditioned beliefs, which would limit their ability to clearly see, hear, challenge and provide support in a holistic way that wasn’t solely about me or them, or based on worldly ideas about what constitutes mental health.

Most therapists probably aren’t thinking in terms that include our connections to one another through a greater field of consciousness that’s beyond geography, brain and intellect, false gods and choices.

I’m not against therapy. It’s just not a good fit for me.

Report comment

Sometimes I wish I could feel at least somewhat sanguine about therapy, but whenever I try to, I feel as though I’m betraying myself.

That’s never a good fit for me.

Report comment

I’m sorry, Birdsong. I can understand why you’d be wary.

Recently I’ve been reading “Trauma and the Soul: A psycho-spiritual approach to human development and its interruption” by Jungian analyst, Donald Kalsched.

I love books where I can randomly open to any page and usually discover something both relatable and that leads me to make other connections, without my having to begin at the beginning of the book and reading straight through.

It’s amazing how ‘therapeutic’ it can be to read about other people’s struggles and efforts to find healing, with healing not being synonymous with cure.

I’ve also learned to separate the message from the messenger. Sometimes I can and other times I can’t. I feel this way about most Jungian authors and even Jung himself.

For the sake of anyone else reading this, it’s worth repeating I’m definitely not against therapy in and of itself.

Report comment

Thank you, Tree and Fruit, but I’ve come to see my wariness as a gift.

I love good books, too! I looked up “Trauma and the Soul” on amazon. It sounds wonderfully fascinating, but right now a bit out of my price range.

Sometimes I think there ought to be more therapists with a spiritual orientation, but then I remind myself what a hornet’s nest spiritual matters can be, especially with people some of whom are already primed to go on an ego trip.

Report comment

Wariness can be a form of discernment. It’s good to be cautious and to vet things, without accepting people or their words at face value. I’m blessed in that my intuition usually kicks in at some point, either immediately or based on more information and/or exposure.

Not sure how someone would vet a potential therapist. Or if there’d be a way to have a one-on-one conversation where specific questions could be asked and answered. I have a feeling the kinds of questions I’d have in mind wouldn’t be addressed directly.

About the book . . . I don’t know where you live (or what your particular circumstances are), but some libraries carry books like the one I mentioned; out of curiosity, I just checked and ours does.

Over the years, our library has allowed me access to videos, music, books and even a free movie channel on our Roku TV.

Report comment

I found a YouTube video of Mick Cooper demonstrating a Person-Centered therapy session, using an actor playing the role of his female client. There are two versions; I watched the one with added commentary.