Blood Orange Night: My Journey to the Edge of Madness by Melissa Bond (Gallery Books/Simon & Schuster)

Melissa Bond’s memoir of benzodiazepine addiction, withdrawal, and recovery is a gripping read. The book tears along with the pacing and gut-punch emotional revelations of a novel or a screenplay—and it’s easy to picture some of her darkest moments projected on widescreen in high definition. It is beautifully, brutally cinematic, its vivid storytelling bringing to life an all-too-common scenario: The saga of a first-time mom who has trouble sleeping and is handed a prescription for Ativan.

Melissa Bond’s memoir of benzodiazepine addiction, withdrawal, and recovery is a gripping read. The book tears along with the pacing and gut-punch emotional revelations of a novel or a screenplay—and it’s easy to picture some of her darkest moments projected on widescreen in high definition. It is beautifully, brutally cinematic, its vivid storytelling bringing to life an all-too-common scenario: The saga of a first-time mom who has trouble sleeping and is handed a prescription for Ativan.

That prescription is doubled. Then doubled again. Then, on top of that, she’s put on Xanax. So it goes until Bond’s skin is on fire, her legs buckle, and she plunges into a hell all too familiar to those struggling with benzos. After doing some research, she has her awakening—and then endures another kind of hell as she starts to taper off. So begins the fiery episode of the title:

“Heat runs like a fierce, howling wind up my back. I don’t know where my body begins or ends. Colors explode in my vision, raging like a wildfire through my head. The blood orange night turns red and screams through my eyes. The room titls around me. Consciousness shuts again. Velveteen black. Silence. Time stretches and disappears. A dark figure hovers at the doorway, watching me. I can feel the dark like a cold fabric wafting. I can feel Death wait and then turn. Hssssss. And then there’s nothing.”

And she collapses, barely willing her limbs to crawl.

Bond, a poet and journalist whose writing has appeared on Mad in America, slings words with lyric ferocity as she describes her agonies and her efforts to find some way forward. She also describes the ups and downs of her marriage and home life, as her husband retreats and their daughter—one of the story’s brightest lights—is diagnosed with Down Syndrome.

All of this is so relatable on a human level, and so rivetingly told, that it could—should—crack a wedge into mainstream readership. It could—should—reach others who, like her, might be considering benzodiazepines without a complete understanding of their addictiveness and iatrogenic dangers. And who, like her, might have doctors who fail to understand that themselves. Or if they do, don’t care.

“What kind of medicine is this?” she asks at one point. “What kind of medicine makes people this sick?”

Rhetorical questions both, but they have to be asked—and they deserve to resonate far and wide.

*****

Grifting Depression: Psychiatry’s Failure as a Medical Science by Allan M. Leventhal with Sharaine Ely, with a foreword by Mad in America founder Robert Whitaker (Peter Lang)

This concise, determined book is dense with history, dense with facts: In taking psychiatry to task for its many flaws, Leventhal trains his eye on the all-out scam of inferior, cherry-picked research being used to push psychiatric diagnosis—and then push the drugs being marketed as the primary treatment. He chose to zero in on depression specifically because, he writes, “It is the best example of the problem, having become in just a few decades, and without scientific justification, the #1 psychiatric diagnosis.”

This concise, determined book is dense with history, dense with facts: In taking psychiatry to task for its many flaws, Leventhal trains his eye on the all-out scam of inferior, cherry-picked research being used to push psychiatric diagnosis—and then push the drugs being marketed as the primary treatment. He chose to zero in on depression specifically because, he writes, “It is the best example of the problem, having become in just a few decades, and without scientific justification, the #1 psychiatric diagnosis.”

The resulting volume covers considerable territory: The distinction between “depression” and sadness, a normal response to loss; the medicalization of the psychiatric field and the construction of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM); the bogus disease theory; research compromised by psychiatry’s relationship with pharma, including the NIMH-sponsored STAR*D study that was slyly crafted to leave out negative results ; and the layers of harm endured by those who were duped into thinking SSRIs have far greater efficacy than they do.

Grifting Depression lays out everything in plain English, articulating the arguments and outlining the data with an astute knack for pointed repetition and everyday adages. It’s also packed with italicized declarations, each one pointing to some cause for frustration or bafflement with the state of affairs. Describing Stuart Kirk and Herb Kutchins’ 1992 FOIA request into the data used in assembling DSM-III, Leventhal writes: “No new scientific data were behind any of the diagnoses. . . . Nor were the decisions about the disorders medically based. No new medical data were cited for the diagnoses.”

With each such italicized snippet, you can almost hear him exclaiming; you can feel his anger at not merely the failures of science but the deliberate subterfuge that recast them as successes.

In its final chapters, the book outlines the history and principles of behavioral therapy and lays out the research confirming its efficacy and superiority to antidepressants. “It did not come from a committee of doctors voting on a treatment that just happened to be in their financial interest,” writes the author, whose long career as a clinical psychologist includes tenures with American University and the Walter Reed Army Medical Center. In this case, the science is there; the studies say so. He calls for more.

For Leventhal—and for anyone paying attention—the conclusion seems obvious. “Scientific evidence directly challenges how mental health care for depression is being delivered. It is past time for the contrived evidence supporting the medicalization of mental health care to be examined for what it is and what it has wrought,” he says, “and for things to change.”

*****

Trigger Points: Inside the Mission to Stop Mass Shootings in America by Mark Follman (Harper Collins)

In the aftermath of shootings in Highland Park, Illinois, and Uvalde, Texas, no book could feel timelier than Follman’s. Still, we know that each latest incident of American bloodshed will quickly be supplanted by the next. There will always be new shootings. Follman’s book will always feel timely—and, paradoxically, outdated.

In the aftermath of shootings in Highland Park, Illinois, and Uvalde, Texas, no book could feel timelier than Follman’s. Still, we know that each latest incident of American bloodshed will quickly be supplanted by the next. There will always be new shootings. Follman’s book will always feel timely—and, paradoxically, outdated.

But Follman, a journalist and national affairs editor for Mother Jones, takes a forward-looking approach to such bloodshed and the cutting-edge projects designed to prevent it—training a lens on behavior-oriented efforts to identify or predict, and thus reduce, the emergence of likely shooters. As he explains in his introduction:

“Greater recognition of warning behaviors, both among trained professionals and everyday citizens, has vast potential for reducing mass shootings. What if there existed a community-based model for intervening constructively with troubled people well before they armed themselves and went on a rampage? What if, instead of so much effort on shooter response, we put a lot more on shooter prevention?”

A vital question, and one he answers by profiling the FBI agents and others behind threat-assessment teams and related programs. Focusing on alarm-bell behaviors such as gun purchases and admiration of past killers, those he dubs “the new mindhunters” do their best to scout out shooters before they shoot—and engage family, friends, and community members in the process. Follman illuminates the mindsets of past shooters and details past incidents, most strikingly in a you-are-there depiction of the Virginia Tech shooting of 2007 that left 32 dead and prompted survivor Kristina Anderson to hit the speaking circuit in appeals to emphasize prevention.

Ultimately, Follman, and those he quotes, point to causes and conversations beyond the usual “mental illness” narrative that invariably pops up after such killings. As he and others note, most shooters have not been diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder; based on their lack of DSM-recognized symptoms, most wouldn’t be. They don’t “snap”; instead, they plan their atrocities methodically and act with resolve. Meanwhile, most people diagnosed with mental disorders aren’t violent.

But there’s a wider truth here, one not articulated in Trigger Points: That all of this only points to the failures, even the absurdity, of the DSM’s definitions of disorder and ongoing pathologization of normal emotion. Grieving for more than a year might prompt one diagnosis; struggling after trauma prompts another. But what’s more disordered, after all, than stockpiling weapons, scheming to kill innocents en masse, and then ripping bodies to shreds with an AR-15?

Maybe, at some point, the conversation will shift to the broader implications of what it means to be sane—and what it means to be human.

*****

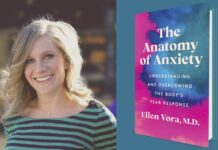

The Anatomy of Anxiety: Understanding and Overcoming the Body’s Fear Response by Ellen Vora (Harper Wave)

What is anxiety? Why do we feel it? How can we shake it off—sometimes literally? What do we need to learn about our deeply ingrained stress response, and about ourselves?

What is anxiety? Why do we feel it? How can we shake it off—sometimes literally? What do we need to learn about our deeply ingrained stress response, and about ourselves?

Answering such questions is the aim of Vora’s accessible read, which is both a dissection of anxiety’s mechanisms and a self-help book.

Among the many concepts outlined within is her marked distinction between “true” and “false” anxiety: The former is the body’s reaction to something askew in our lives that demands listening and requires change; the latter is its reaction to lifestyle and diet. In a chapter titled “Body on Fire,” she considers the impact of inflammation and autoimmune responses, which—“by evolutionary design”—lead to a social retreat and symptoms that “bear an eerie resemblance to what we call depression.” What helps? Eating right, sleeping well, time in nature. Creativity, community, connectedness. Also: “It’s important to foster our connection to pleasure, whether it’s through orgasm or opera or chocolate.”

All of this seems obvious, or should be—but the obvious is too often overlooked in a paradigm fixated on diagnosis and drugs. Vora, a holistic psychiatrist who also works as an acupuncturist and yoga instructor, packs her book with alternative approaches and nuggets of wisdom. As she acknowledges, some of these might or might not jive with everyone’s personal schema and circumstances, needs and beliefs.

Nevertheless, the book is dashed with insights and optimism, some of it unexpected: Pointing to continually skyrocketing rates of anxiety, she observes, “Our genes cannot adapt so quickly as to account for our recent catapult into anxiety. It stands to reason then that we are increasingly anxious because of the new pressures and exposures of modern life—such as chronic stress, inflammation, and social isolation. So, odd as it may sound, this recent acceleration is actually good news.”

The Anatomy of Anxiety includes a few statements that either reassure “the lucky ones” who find some benefit in psych meds that she is not trying to dissuade them, or express support for such drugs in general (e.g., “I am grateful for the advent of antidepressants and other medications…”). This feels out of place, even discordant, in a holistically minded work that’s open about the drugs’ shortcomings and withdrawal risks. Overwhelmingly, the thrust of the book is rooted in non-pharmaceutical approaches, instead calling out the errors of the biomedical narrative and reframing anxiety in more getable, doable, and compassionate terms. Drugs have little to do with it.

In an appendix, she itemizes the herbs and supplements she sometimes recommends in her own practice—but notes that such bottled nutritional add-ons “are not the focus of my approach to anxiety. . . . I think the pill-for-an-ill idea of conventional medicine misses the point; just as I don’t think anxiety is a Lexapro-deficiency disorder,” she writes, “it’s not an L-theanine-deficiency disorder either.”

****

Desperate Remedies: Psychiatry’s Turbulent Quest to Cure Mental Illness by Andrew Scull (Harvard University Press)

How do you rebut the bible? With an equivalently epic tome.

How do you rebut the bible? With an equivalently epic tome.

Granted, Scull’s massive undertaking is 480 pages including notes, or only half the length of the DSM-5’s 947. And it was not, repeat not, pieced together by a committee flush with money from Big Pharma. But it was written with a sense of mission, calling out false prophets in the history of psychiatry with meticulous care and calm indignation.

“We need to be honest about the dismal state of affairs that confronts us rather than deny reality or retreat into a world of illusions,” he says at the outset. “Those, after all, are classically seen as signs of serious mental disorder.”

From start to finish, Desperate Remedies is a stunning assemblage of research, histories, individual stories, and the many serial outrages inflicted by psychiatry in the name of medical progress. Boiling its contents down to a compact review would be next to impossible: All the corruption, all the drugs, all the blasts of ECT, all the brain surgeries sliced through with breezy confidence by lobotomists.

Consider just one: Walter Freeman, who dreamed of being “the Henry Ford of lobotomy” and cranked out six-minute transorbital ice-pick swipes in what Scull describes as “an assembly line.” In the summer of 1946, he headed out west in a camper he dubbed “the lobotomobile,” stopping en route to demonstrate and popularize his techniques. Wholly discounted were those who died or suffered memory loss after such procedures.

Six years later, the first edition of the DSM was published—and so began another bendy leg in psychiatry’s journey, evangelizing and spreading another kind of harm.

A prominent sociologist and social historian who has authored several other books on medicine and madness, Scull digs wide and deep in his excavation of psychiatry. The book unpacks the influence of Freud; the history of asylums, institutionalization, and deinstitutionalization; the efforts of psychiatry to justify itself as a practitioner of hard science and somatic cures; the rivalries at play in various corners of the field; the ebb and flow of theories and treatments that rise up, seize the profession, become popular, and remain so despite science that demonstrates questionable results at best, injuries and death at worst.

In the end, he concludes, “We need a very different approach. The fixation on the biological has led to another kind of stasis. . . . We should seek, in confronting madness, to avoid premature and uncritical enthusiasms and easy solutions. It would help enormously if psychiatry were to be more honest about the limits and imperfections of its knowledge.” So it would.

Can’t judge a book by its cover, but these ones do look interesting.

Joshua

Report comment

Thank you Amy for your reviews! Awesome! I just purchased “Blood Orange Night!” It is a great book! I love it!

Report comment