Richard Schwartz, Ph.D., is the creator of Internal Family Systems, a therapeutic model that rejects the notion of a “mono-mind” in favor of a more inclusive, manifold approach that regards each person as a bearer of distinct “parts”—each one shaped by past experiences. Such parts might include traumatized inner children or other “exiles,” as well as “protectors,” “firefighters,” or similarly distinct roles.

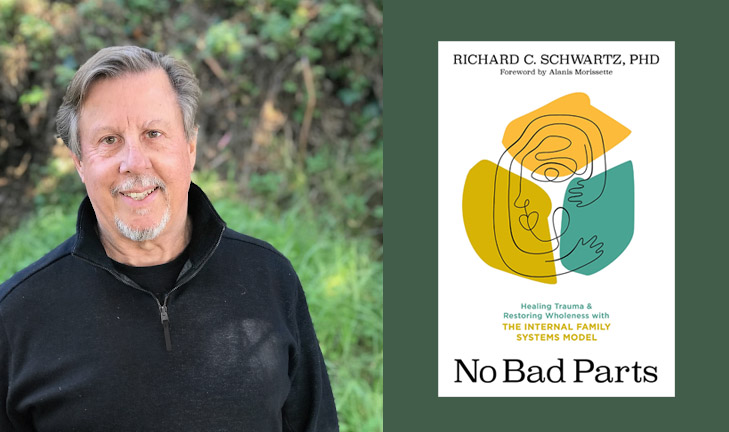

Originally trained in systemic family therapy, Schwartz earned his Ph.D. from Purdue University and started developing IFS in the 1980s. He’s published five books, including Internal Family Systems Therapy, Many Minds, One Self: Evidence for a Radical Shift in Paradigm, and, most recently, No Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with The Internal Family Systems Model.

Schwartz, who taught for many years at the University of Illinois at Chicago and Northwestern University, is currently on the faculty at Harvard Medical School. For more on IFS, see ifs-institute.com.

The following interview has been edited for space and clarity.

Amy Biancolli: How would you normally describe Internal Family Systems to someone? Incorporating, for instance, a rundown of the various parts and the concept of everybody having an internal family?

Richard Schwartz: IFS is a different paradigm for understanding the mind that says that rather than being a sign of pathology, it’s the nature of the mind to have what I call “parts”—what other systems call sub-personalities, or ego states, or voices. In multiple personality disorder, they’re called alters. It’s the nature of the mind to have them.

We’re born that way—and we’re born that way because they’re all valuable. We need their resources to make it in life and to thrive. Trauma and attachment injuries, and things like that, forced them out of their naturally valuable states into roles that can be destructive and sometimes were necessary at some point in your life. But they often are frozen back there, frozen in time during a trauma, and they think you’re still five years old. They think they still need to do what they needed to do back then.

I recently wrote a book called No Bad Parts, which was trying to make that case: that so many things we think of as psychiatric diagnoses and illnesses are really just the activities of a lot of these protective parts.

When you suffer that way, some parts are very vulnerable and young—what often are called “inner children”—and they’re the ones that get hurt the most, because they’re the most sensitive. They take on what we call the “burdens” of worthlessness, or terror, or emotional pain. When they get burdened that way, when they carry those feelings, they’re not so much fun to be around.

Before they get hurt, or scared, or ashamed, they’re lovely—because they’re all kinds of innocence, and playfulness, and creativity, and openness. But after they get hurt, now they can have the power to overwhelm us and pull us back into those scenes and make us feel the things we didn’t want to feel again. We tend to want to lock them away inside, in inner basements or caves or abysses, and just move on, not realizing that we’re moving on from our most precious qualities just because they got hurt.

Those we call “exiles,” because they’re locked up inside, and we have parts that do their best to try and keep them that way. When you have a lot of exiles, you feel more delicate, and the world feels more dangerous, because so many things could trigger them, and if they get triggered, then they have the power to overwhelm you.

Then a lot of other parts are forced into “protector” roles, some of whom try to protect you by managing your life so that the exiles don’t get triggered. They’ll tend to want to keep you a certain distance from relationships, or make you look perfect so that you don’t get rejected, or make you achieve a lot so you get accolades to counter the worthlessness, or take care of everybody around you so that they depend on you. There are a lot of different “manager” roles.

But despite the best efforts, still, your exiles get triggered sometimes. So there’s another set of parts who are on standby, and if you suddenly feel a wave of terror or pain, they’ll immediately go into action to take you away in an impulsive way, in a reactive way. They’re desperately trying to get you higher than the flames of emotion of the exiles, or distract you until they burn themselves out. We call those “firefighters,” because they’re fighting these raw flames of emotion that the exiles carry.

So that’s the very simple map to the inner territory.

In addition to all of that—and probably the most important discovery of IFS—is that there is also a kind of essence in everybody that’s just beneath the surface of these parts, such that when they open space, it pops out—and contains all these wonderful what I call “C-word” qualities, like calm and curiosity and compassion and clarity. That is not a “part” like the others. That’s what clients said when I asked, “What is that?” They’d say, “That’s more myself, that’s not a part.” So we call that “the Self.”

It turns out that everybody has that. It can’t be damaged, and it’s just beneath the surface of these parts—so that when they open space, that “Self” emerges and knows how to heal, and knows how to help these parts transform, and knows how to heal external relationships. A lot of the work is designed to access that, and then when people are in that space, start to heal these parts.

Biancolli: If you could describe how IFS differs from the usual approach, the usual treatment, the usual biomedical paradigm: How is this different? What distinguishes it?

Schwartz: Yes, so there are a couple of different paradigms, one being that these diagnostic categories are symptoms of disease, and that they should be just treated as such, and not thought to be anything different than that. When you have a disease, you look for a medication, and so psychiatry has been very, very medication-focused. Then the other paradigm is that it’s some kind of cognitive distortion that needs to be corrected, and so CBT is set up to try and challenge the distorted beliefs that surround the issue.

From my point of view, neither of them get to the limbic level of what is going on with people, which drives these activities.

Biancolli: Do you think that IFS digs a little deeper, or frames the issues differently? What distinguishes it from CBT, for instance?

Schwartz: Well, rather than thinking of the part of you that’s phobic, for example, as just a distorted cognition, we think of it as a young part of you that’s stuck in a place that’s probably pretty scary in your childhood.

Now, that’s a huge difference, because if you think of it as a cognitive distortion, you’re going to argue with it or try and expose it. There’s this whole thing called exposure therapy, where you try to have the person face their fear and desensitize that way. Which is torturous for many people, and often doesn’t work.

So instead, if you think of it as a young part of you that’s still very scared because it’s stuck in a terrible place, then you’re going to open your heart. You’re going to focus on it, ask it to show you what happened to get so scared in the past—to see yourself as a child, and you’re in a scary place. It’s been waiting for you to come and rescue it.

Once it feels like you really understand what happened, and how bad it was, then I would have you go in and be with it, back there, in the way that that child needed somebody at the time—until that child was ready to leave with you. We could literally retrieve these parts from where they’re stuck in the past. Once that happens, we can help them unload the fear, because now they trust they’re safe, and they don’t need it anymore. We have a process we call “unburdening” where we help these parts give up the extreme beliefs and emotions they got from these scenes.

At which point, it’s like a curse has been lifted, and they’ll transform into their naturally healthy, valuable states. Then we can bring in all the “protectors” who were trying to keep it locked up—or in some way, deal with it—to see they don’t need to do that anymore. They don’t need to make the person phobic, or anything. And help them into new roles as well. So it’s just a totally different paradigm.

Biancolli: Just to reiterate: Some of the many parts that people have might be, as you said, an “exile,” which could be an 8-year-old child who was traumatized. Then you’ve got the “protectors,” who are trying to make sure that child isn’t going to be in a situation where the child is triggered. Then you’ve got all these other pieces that are trying to basically cope with all that happened to them.

Schwartz: Right.

Biancolli: Does it boil down to a lack of judgment? It’s inviting people to say, “Okay, you have this child inside you somewhere. Regard this child almost from a distance, with compassion, and look at the child without judgment? Look at these other pieces which might be more difficult, also without judgment? Is the lack of judgment a big piece of it?

Schwartz: Just one piece of it. I don’t say, “You have this child inside of you. Let’s go find her.” I would say, “Focus on the fear. Find it in your body, and see if you can get curious about it, and then ask what it wants you to know.” And then people spontaneously will either see a child, or they might see an animal. They’ll see some image of the fear. Then I’ll help them get compassionate toward it, and so on. It’s very non-directive, in a sense. Just helping them get curious about what’s in there, and then, once they learn what’s in there, get compassionate about it and relate to it in a compassionate way.

Biancolli: So it’s more open-ended.

Schwartz: Yes.

Biancolli: Following their leads.

Schwartz: Exactly.

Biancolli: Could you speak a little bit to your own a-ha moment—the origin story? How you came to IFS?

Schwartz: I was trained as a family therapist. I have a PhD in that. I was working in a psychiatric context, and I was very eager to prove that family therapy had found the holy grail. I decided to do an outcome study with bulimia, and with a colleague, rounded up 30 bulimic kids and their families—and found, to my frustration, that straight family therapy didn’t do much.

Out of that frustration, I began asking what was actually going on inside of them, and they started teaching this to me. Because they would talk about how when something bad happened in their lives, this critic would start to attack them and call them names—and that would bring up a part that could make them young, and feel empty and alone and worthless. That feeling was so distressing that in came the binge to take them away from it. But the act of the binge would bring the critic back, and then that would, of course, make that worthlessness come back, and then that would make the need for the binge to come back.

As a systems thinker from family therapy, this sounded familiar—it sounded like one of these vicious cycles that people get caught up in. So I got very intrigued, and initially made the mistake of trying to fight with the critic, and trying to control the binge. I kept doing that even though kids were getting worse.

Then I had a client who, in addition to bingeing and purging, cut herself on her wrists—and that was so dreadful to me to have somebody doing that on my watch. So one session, I decided I wasn’t going to let her leave my office until the cutting part had agreed not to do it, and so we both badgered the part for a couple hours. It finally said, “I won’t. Okay.”

Then she came back in the next session and had a big gash down the side of her face. I spontaneously just collapsed emotionally, and I just said, “I give up, I can’t beat you at this.” And the part said, “Well, I don’t really want to beat you.”

That was a turning point in the history of this work, because I shifted from that coercive part of me to just being curious and just said, “Okay, then why do you do this to her?” And it proceeded to tell me the story of how, when she was being sexually abused, it had to get her out of her body, and it had to contain the rage that would get her more abuse.

Now I’m not just curious, but I have an abiding appreciation for the role it played in her life, and I could convey that to her part. It broke into tears, because everyone had demonized and tried to get rid of it, and it talked more about how it still needed to do this. But as it did, it was clear to me it wasn’t living in the present, because her present context wasn’t dangerous. It was really still living back when she was six or seven, getting abused.

So with all of that, I just started to experiment with trial and error: Okay, how can we change some of this stuff? And not from a coercive place, more just curious. If I’m proud of anything, it’s that I allowed my clients to teach all this to me, and lucky to have some clients who could really straighten me out when I was going off in the wrong direction.

Biancolli: You just mentioned your coercive part. What have you come to learn about yourself? Have you applied IFS to yourself? What are the epiphanies you’ve had?

Schwartz: First of all, that I have a “Self”—that was news to me, too. And that I also had all these parts that had been running my life that were based on some of my own traumas that were getting in the way. Some of them sort of goaded me into creating this, because I came out of my family with a lot of worthless feelings and had to justify my existence. They helped me put up with all the slings and arrows I encountered trying to bring this new paradigm.

Then there were parts that would get in the way with clients, because I probably would have been diagnosed ADHD as a child, and so it was hard to maintain a real focus sometimes, and I’d be distracted with clients, or bored with clients. I was lucky, again, to have clients who would call me on that. If I’m proud of anything about that, I would own it and I’d say, “You’re right, there’s a part that took me out. I’m going to work on that.” So my main job was just to become a clearer vessel for bringing this, and get my ego out of the way, and all of my parts to let me lead in a more Self-led way.

Biancolli: Getting back again to the disease model, one is the idea that we just have one mind: In the book, you call it the “mono-mind.” Then there’s this idea that simply getting labeled makes you feel less-than. Is that essentially what you’re doing? You’re challenging that and saying, no, your job isn’t to slap a label on your clients. You’re trying to understand them, take cues from them, listen to them.

Schwartz: Yes. The pathological label tends to scare therapists and leads them toward more medical kinds of interventions, and isn’t necessary. I find that the DSM is an accurate description of what are mainly just clusters of protective parts that organize in different ways in different people. If you think of them that way, then you’re going to approach them with curiosity, and you’re going to learn how they’re trying to protect, and you’re going to honor them for their service, like you do the military, rather than call them pathological names and try to get rid of them.

Biancolli: There’s a way that I’ve heard people phrase it in terms of trauma: to ask not “what’s wrong with you?” but “what happened to you?” Is that in essence what IFS is trying to do?

Schwartz: Yes. I mean, we are framing all these symptoms as often the product of trauma—not always—if that’s what you mean. Yes, it’s the way inner systems organize after people have been hurt and then abandoned, basically. Because it’s one thing to get traumatized, but then the most pernicious part is the aftermath, where you lock away the parts that got hurt and try to stay away from them from that point after. Virtually everybody in our culture is taught to do that, and if you have a lot of “exiles,” like I said, you’re going to need a lot of extreme “protectors” that cause symptoms.

Biancolli: What were your goals in writing No Bad Parts? And do you have a sense of mission—of wanting to spread the word with these ideas?

Schwartz: Yes, that was my goal. I had been focused for most of my career on training therapists and been fairly successful on that, and it just feels like time to try and change the culture. This is a paradigm that could make a big change in our culture, and so my goal was to begin that process of bringing it more to the public.

Biancolli: You’re also doing training work for mediators, for conflict resolution, and from what I understand, there’s an international component, a policy component. Is this part of a wider effort to change how we relate to each other?

Schwartz: Very much, yes. I’d say in the last decade I decided, and it sort of happened spontaneously, to try and bring it to higher levels of system and not just to psychotherapy. I’ve had a number of different opportunities to do that, and so there are a lot of different projects in that direction.

Biancolli: The approach reminded me of the Hearing Voices Network, that whole movement of people who hear voices and don’t try to suppress them—try to listen to them and learn from them. Do you see a parallel?

Schwartz: Very much. I’m a supporter of that network. I haven’t been actively involved, but I would say they understand the voices in a similar way, and instead of being afraid of them or fighting with them, they’ve learned to listen, which is a good first step. It doesn’t necessarily heal their systems, but at least you’re not polarizing inside the way most people do when they start to “hear voices”—because the voice is usually one of these parts. It just needs to be listened to and brought out from where it’s stuck in the past.

Biancolli: You also refer, at one point, to an inner orchestra—having different musicians playing different instruments, or singing different parts in a choir. When you’re making music with other people, you’re listening, and you have to cooperate or it falls apart.

Schwartz: Yes.

Biancolli: That struck me as a really interesting analogy—and correct me if I’m wrong, but you’re also almost asking us to take a look at our different parts in a literary sense. Or is that pushing it?

Schwartz: What do you mean in a literary sense?

Biancolli: For instance, my favorite book is War and Peace. I love the family dynamics, and all the parts pop out, and you understand them almost by looking from above. I wondered whether it’s too much to say that, in a way, we have those parts inside of us. We’re all carrying around a story, a War and Peace.

Schwartz: Yes. That’s very apt. I like the metaphor, and yes: You, as the reader, are just observing. With a book like that, you have some judgments about some of the characters, but mainly you’re just kind of watching the story unfold. So that is a good first step, is getting some distance from these parts and noticing how they relate to each other, and doing it from a place of mindful acceptance. But again, that’s just the first step. So what I try to do with IFS is say, it’s not totally compassionate to watch suffering beings parade by. Even if you’re accepting them, they need to be helped, and you have the wherewithal to do that.

Biancolli: Has any of this surprised you? Are you still surprised sometimes, or are you still having insights?

Schwartz: Yes. That’s the wonderful thing about this gift I’ve been given to bring. It’s been amazingly entertaining and adventurous. It’s been a constant learning process, and continues to be. I’m still learning new ways to work with the systems. I’m learning new things about parts, and I’m learning new ways to work with my own—or learning about new parts I need to work with. Put it that way. It can be quite an adventure.

Biancolli: This is a quote from your book: “Your inner world is real. […] They are inner beings who exist in inner families.” Have you met resistance with that? How often does somebody say, “Yeah, no, sorry, I can’t do that”?

Schwartz: Not nearly as often as it did as I was starting out. That was almost always the reaction, and I was guilty of it, too. I started to work with parts, but assumed that they were just metaphors for different thoughts and impulses and so on. I went to hear a woman named Sandra Watanabe talk, who had developed something called the “Inner Cast of Characters” back then, and she was talking about them as if they were real. I came up to her and said, “You don’t really think these are real, do you?” She said, “No, they’re very real.” And I walked away thinking, how naive.

Then a few years later, I was totally convinced of their reality, too—and have been ever since.

And it is a tough sell in this paradigm, partly because multiplicity has been so pathologized, like we’ve been saying. That either you’re crazy and you have parts, you hear voices, you have multiple personality disorder—or you have this one mind that just has different thoughts. There’s no in between.

Biancolli: What will it take to change the paradigm—whether with IFS, or with any other approach? In general, what will it take for that to change?

Schwartz: It does seem people are very, very skeptical. Once they try it, and once they actually enter these inner worlds, not all but many of them really can shift fast. Because it is so real when they get in there. One approach has been to just try and get more and more people to try it, and that actually has panned out. I mean, IFS has become very, very popular and influential because, finally, lots of people have tried it.

Then the other approach has been to try and do a lot of research, particularly with difficult populations that traditional models don’t have much luck with. If I can show that we have these amazing results, then that’ll pique the interest—even if they don’t want to think of it as real—of the traditional bastions of the field, because they’re so desperate to find effective solutions to these problems. I’ve been talking to a state senator in Washington State about doing an outcome study with IFS and domestic violence, for example, because they’ve pretty much given up on treatment for domestic violence, because the model they were using was proven to be worthless. But if I can show that we can actually change that, because that’s the root of so many other issues, then people get interested.

Biancolli: Something else you talked about in the book was this obsession we have as a culture with sin, and the idea of somebody being innately wrong. Is that also something that people have a hard time overcoming?

Schwartz: Yes. Particularly religious people have trouble. But that view of people, it’s had a big influence on our culture, the idea that there is sin and evil inside of us—which I don’t deny, because a lot of these “burdens” would qualify. But they aren’t the parts, and then the parts get misidentified as the evil impulse. So instead of trying to heal the part, you try to throw it out—the baby with the bathwater. So that’s what I’m trying to clarify.

Biancolli: I’m also interested in the exercises you have in your book encouraging people to observe their inner parts, understand their inner parts, and in some cases observe an inner part who tends to get triggered. Have you heard from readers who’ve responded to that? Have you gotten any feedback?

Schwartz: Yes. People seem to be able to do it. Some people get the audiobook version because they need to listen while they do the exercise. But a lot of people, I was amazed, could just do it from reading the exercises in the book. I really had no idea how well this would be received by the public, and I’ve been very heartened. I mean, if you just look on Amazon at the feedback, so many people say their life’s been changed just by reading the book and trying the exercises.

Biancolli: I was additionally curious about the “laws of inner physics” and the idea that if you simply ask a part not to overwhelm, that it won’t. That you don’t have to be afraid even of the darkest part. You can just ask it not to overwhelm, and it cooperates.

Schwartz: If they think it’s in their best interest. You’ve got to convince them that it’s in their best interest to not overwhelm. Yes.

Biancolli: Does it take a while to reach that point?

Schwartz: Not usually. Let’s say we’re working with an exile that carries a lot of pain, and the client complains—because whenever she opens the door to that, she’s overwhelmed, and can’t get out of bed for a week, or something. I’ll say, okay, let’s talk to that part.

I’ll say, “You do tend to overwhelm her? Is that right?”

“Yeah.”

“Okay. What are you afraid would happen if you didn’t?”

“Well, she’d lock me up again.”

“If we could get her to agree to not keep locking you up, and instead listen to you, would you have to totally take over that way?”

Almost always they say, “No. But I don’t think you can get her to agree to that. She hates me so much.”

I’ll say, “Well, I’ll make sure she doesn’t. That she listens to you. But to do that, I really need for you to not totally take over.”

And if they think it’s in their best interest, then they don’t need to take over. So that’s another way that if you can think of these as sentient beings—which they are—it’s all negotiable. You can negotiate most anything.

Biancolli: You can engage in a dialogue with them.

Schwartz: Yes.

Biancolli: As you were saying, this is not just mental health, but the wider conversations around who we are. It sounds so simple, but ultimately, that’s not easy for a lot of us, is it?

Schwartz: No, it’s not easy—because we’ve been so socialized to think the opposite. That’s a tough sell on the meeting, but once people get the habit of it, it becomes a lot easier. But often, by that time, they’ve already exiled lots of stuff so there is just a lot of work we have to do to bring it back.

I have a schizophrenic illness that orders me to have a schizophrenic part. I do not joke about this. Tis true…so what am I supposed to say to both of these aspects of me?

Look Sir article writer,

I knew about ego splits decades ago. I celebratè it as one of the best ways we can find to heal so many an adverse experiences….BUT…..

thinking about schizophrenia does NOT cure my schizophrenia.

Thinking about malaria does NOT cure a dose of malaria.

What I do know and have written extensively on, is that torture forces a person into being a fractured being just to survive. Like smashing up a jigsaw makes it easier to hide in a pocket or a crevasse of a wall.

1.My schizophrenia comes first.

2. My being bullied by a hallucinated figure comes next.

3. My coping with that tyrannt causes me to delay gratifying the needs of some aspects of me, so th

(My angels just told me you are tired of listening to my schizo memo)

(I shall hush up then and go…. and leave… and… go….and go…..

…. and leave… and go very far….

further

I’m gone now.

Report comment

Ps. I just looked at the Thomas Insel article. It has hundreds of comments.

Lo, most are by dear Birdsong. Sometimes that happens on MIA, people repeat the same stance over and over again. But regards your book this ploy seems to be the opposite of having different parts or different personalities. What you see must be what you get. But for myself I prefer people to have hidden personalities within them, the restrained one, the ruminating one, the excitedly curious one, the open one. When they all contribute to creating but one comment it comes out like a colourful free fresco.

Not so repetitious a tone.

When THE HOOVER DAM explodes you will need lots of extra personalities to have Open Dialogue with the bereaved.

Back biting in the comments section loses the opportunity to prepare elegantly for a number of natural disasters.

Report comment

Daiphanous Weeping, I am not sure about the Hoover Dam exploding. I pray it doesn’t. It would be beyond disaster. However, you are completely correct about the “babckbiting.” It has sadly gotten nearly out of hand. I saw a book advertised on Amazon about a very controversial topic that advertised a “balanced” look at the “pros and cons.” Sometimes, each of us is very guilty of not making their goal to be one of “balance.” This is not about those who have trouble maintaining balance for whatever reason. This is about willing to accept that there are as many ways to look at an issue as there are people and not all are wrong because they seem to be in disagreement with my opinion or life story. And I confess, sometimes, I too am guilty of this and get unfortunately caught up in the moment. Perhaps, we all need more forbearance even those who do see a different side to psychiatry, than just the “anti” side which is valid. However, all sides are valid and no matter your side, you can learn from the other side. Also, no matter your side, by learning from the other side, you might learn something that could truly boost your position. Diaphanous weeping, Thank you for your perspective. Thank you.

Report comment

I feel blessed to have your approval. Your comments take the raw feelings and refine and distil them into crystal clarity. I always enjoy reading what you make of a topic. It is always an unexpected soulsearching authentic response.

I will maybe say more in a while. The breakfast trolley is coming to the ward and my phone needs recharging. But know I love your comment to me. Life is too short for us all to make being “right” the top priority. Being love seems unrewarding but often people heal themselves better via love, and that is the reward we all want. For a well person spreads wellbeing. And you know this compassionate stance. And I admire you greatly for it.

Report comment

The HOOVER DAM did explode yesterday but I believe that was just a test run. I am not sure when a bigger toppling will occur. My predictions can take a decade or five minutes to season. I did get a sense the explosion proper will occur around a solstice time but I may be mistaken over that specific. The main thing is to be vigilant if you work there, on any day. And hope that I am just full of my usual crazy speak.

If and when the dam goes it means the bigger sea flood I often mention is also a possibility. If so then think of what a flood leaves in its wake. Power grid down. Scarce food. No medicines. It is good to be savvy and know that nature does not listen much to politics.

Report comment

Just scanned this and will give a more thorough read later today. This whole idea of separate actors really appeals to me. I have BP1 and, when manic, my anger comes to the fore. Because I am generally so meek and introverted, dare I say “ladylike,” people are alarmed at this furious, toxic entity that I become. In fact, my mania is what keeps me sane. I am not allowed to be angry for various reasons, including that I am female. Without mania, I’d be suffering in silence.

Report comment

People don’t talk about the liberating gift that going mad can bring. Being a feral woman is as free as being a feral cat. I would rather be a feral schizophrenic woman than be an indoctrinated, controlled conformist. Whilst being mad I turn to my own inner authority and expertise. I become sort of bullyproof. So my madness has a long suffering curse but also a blessing in liberating me from any outside coercion.

But now a terrible idea has been given by architects of the latest utopia that accepting schizophrenic liberty, or manic liberty, is somehow being a new version of “conformist”. It means being mad is being oppressed. But at the same time oppression is touted as coming from political inequality. And so what I must have to do is relinquish my mad feral freedom and call that freedom inferior to some puppet masters grander idea of freedom that is political and “for my own good”.

In my estimation the liberty found in madness makes oppression less possible, since a bully cannot lecture the mad while the mad are discounting rules by singing love songs like a troubador at the conformist lecturer.

I am using the “you” word generically here..

Madness is a dreaful suffering. You may believe yours comes from epileptic seizures or brain waves affected by 5G phone masts or genetic quirks or a chemical imbalance or a trauma or polluted rivers or refrigerator parents. Whatever you believe is a likely cause of what bothers you right now is to be respected as your choice to know you in the way you know you. Madness is a dreadful malady BUT as I say, it comes with astonishing gifts and blessings, especially in terms of not having to listen to other people if they come out with logic that has no relevance to you.

Madness is a bit like a gigantic tantrum. Or at least the mad woman is freer than her sober sisters to express such emotion.

Stepping into madness is like stepping onto a Hollywood hall of fame flag stone that says the words…

“I do not care anymore what you all think of me”.

It is a counterpoint to the opposite calling, that of…..

“Consensus opinion”.

But to belong to consensus opinion usually means giving up ferallness. The influence comes from the consensus group and its choice for you. Often “for your own good”. You are not allowed to be your own influencer.

Alice Miller’s book was against people doing fussy controlling things to you “for your own good”.

But now even clear spoken Alice Miller’s works are used by “consensus groups” to lecture you that you MUST read them, and turn each page and absorb each truth “for your own good”.

I never want to be “for my own good”.

I want to mess up my life in any way I please because even my choosing to make neurotic or schizophrenic choices bears my freedom of choice. And what IS for my own good is my freedom to do my life MY WAY.

Report comment

I like what you’re saying here. But at the same time some people are just suffering. I would like people who are suffering to be treated better.

Report comment

It has to be OK for people to experience suffering without having it “fixed.” Psychiatry’s main thrust is to STOP people from feeling x or doing y. Good therapy should rather make it safe for people to experience whatever they are experiencing without judgment or a need to “fix it.” A person isn’t broken because they are suffering. They are just suffering. It’s part of the human experience.

Report comment

Steve, I agree. Fixing is bad. Trying to fix, anyone who didn’t ask for anything, is very bad. But I also think if everyone was ok with whatever suffering they experienced, we wouldn’t have suicides. I would have looked for a way to kill myself if I didn’t have a plan that was improving my situation. Sometimes people are looking for something that would improve their situation. I think the current mental health system is often making people situation worse but I don’t think that means there shouldn’t be any study of how to make people’s situation better.

Report comment

I agree 100 percent! People need HELP, but not because they are BROKEN and need some sort of “repairs.” They need compassion and interest and maybe a few ideas for new perspectives. And they need some HOPE for a better future. Some people can be helpful, but a big part of being helpful is NOT thinking that you know better than the person needing the assistance. The person him/herself is the only one who knows what is going on or what will end up being helpful. The best we can do is facilitate the process.

Report comment

Absolutely, People know what assistance is helpful and what isn’t for their particular situation which they’re more familiar with and have a better understanding of than anybody else. I see CBT as viewing people as broken and needing correction which is why I don’t like it. Although, I may not support all of Richard Schwartz’s theories, I do like that his approach as one of curiosity and his therapy seems more compassionate than many others.

Report comment

I am not sure Christine if you were talking to me?

I see madness in a few ways.

1. It is an emancipation.

2. It a driven crazy by factors, like chemical muddles in the body that is teeming with hormones and other magical chemicals, or chemicals that are artificial and live in our water or first aid cabinets, like lead and mercury and forever plastics, or it is from trauma, or it is from other humans being horrible to other humans, or it is from bullying, or abuse or cruelty.

Since the Mad Pride article seemed to focus on the celebratory angle I only spoke to the emancipating aspect of madness here.

I agree on the need to end suffering. Although I would be honest here and say thay a little non harmful transient suffering in the form of challenges, like sky diving or cliff climbing, are more like positive vital excitements. I am not for a life of no discomfort. Being kept like a cosseted, vet pandered, shampooed poodle is bad for the inner animal.

Report comment

Hi, I was speaking in a general way. Ím pulling from my experience and not looking to speak for anyone else. There suffering that can be settle by looking at what the suffering brought to you in increased knowledge, insight, talent that you didńt have before. I feel it´s possible for people to embrace the good things their suffering brought and learn to cope with what isńt. But sometimes I feel the suffering has to be lessened. In my case, I felt I had to look for a way to lessen it. I was too overwhelmed by it. So I found Richard Schwartz theories interesting. Even though it doesńt fit my experience entirely I do think he brings a lot to the conversation.

Report comment

removed for moderation

Report comment

removed for moderation

Report comment

This is an interesting concept, however, dare I say, not entirely new. However, the author has done some excellent thinking about this. I think back to the 1970s when Transactional Analysis was all the rage and people were trying to identify their parent, adult and child. I have seen other self-help books which invite the reader to distinguish and identify different parts and roles within themselves. What is best about this is its basically non-drug approach. As with all theories, I think it may not work for everyone, but also as they the “patient” must also want it to work. But then, what I have noticed lately is that there seem to be many psychiatrists and therapists who really don’t want their patients to improve and their patients basically “buy” into that. But then, sometimes, some people use excuses so they can maintain their diagnosis.However, their are others who feel their diagnosis fits them as completely correct. Thus, I say, this seems to be not for everyone. Thank you.

Report comment

I remember the first time I heard Richard Schwartz speak of IFS during a seminar I attended. I was excited because I felt IFS was getting into the ballpark of a better understanding of psychological problems. I respect that after Dr. Schwartz found that the therapy he was using, didn’t help, he investigated why. I respect that he listened to his clients in an effort to understand why. I feel psychology needs more people to respond as Richard Schwartz. Currently, I see that most in the field ignore, deny or blame the cooperation of their clients for failures in treatment

Based on my own experience there are elements of his theories I agree with, others that I don’t.

What I agree with:

1. Not looking at psychological issues as abnormalities or disease.

2. How his theory differ from CBT. I agree that a problem such as anxiety/phobia come from having been in a scary place and still carrying emotion from it. I believe looking at such problems as a distorted cognition that needs to be corrected leads to treatment that inflames the problem.

3. I do think, what he calls the self (I’ll say who you were before the trauma) does become trapped under anger, hurt, fear. From my experience, every time positive feelings of the self are brought to the surface there is some healing. Positive feeling need not be pulled up through therapy. I think a positive relationship is better. Activities that bring up good feelings of oneself or others is better.

4. In his therapy, he lets the client take the lead. I agree with that but I still feel probing a trauma is potentially problematic.

What I disagree with:

1. That there are innate parts that come out during a trauma. In my experience I feel the parts were the result of the trauma. I don’t see them as coping mechanisms that came to the surface to deal with the trauma. I see them as feelings, perceptions, patterns of interaction that occur during the trauma and stayed with me because the trauma couldn’t be understood and was left unresolved. I, also, don’t agree that the parts will always be there even if you obtained an understanding of what happened and worked through the emotion. In my experience the separate thoughts, feelings and perceptions did integrate into one viewpoint, without emotion connected to it, after I obtained a understanding of what happen and worked through the emotion around it. But closure can be impossible to obtain and consequently the parts never leave.

2. I think the possibility of becoming overwhelmed when traumas are probed is a legitimate concern. One can’t just decide not to be overwhelmed. I don’t agree that through a discussion with a part (I won’t exile you?) the part won’t overwhelmed. My experience is the intensity of thoughts, feeling etc. comes from how much there is in what is referred to as exiles. I know in the beginning of my psychological struggle, I would feel anger at a intensity that was scary. I physically felt it not just emotionally. When it did come to the surface, it would be there for hours. It was a severe stress on my nervous system that I physically felt. I did gradually reduce it but not by negotiation with a part or through a decision. It lessened as I work through what were my exiles. A number of years ago there was a 60 minutes report of people who went into therapy and after considerable probing of past trauma they were left with emotion always on the surface and that emotion was disabling them. They could no longer exile the feelings and keep them box away so they could function. They were in a worse situation than before the therapy. So although bringing thoughts, memories, feelings may allow their release some of the time, I don’t think it’s risk free.

3. If I understand Richard Schwartz and Gabor Mate (someone I feel has made a positive contributed as well) correctly both believe that people become stuck in a trauma because their thoughts and feeling never had a voice at the time of the trauma. That doesn’t fit my experience. During my experience I was voicing my thought and feelings. However, I didn’t understand what I was dealing with and what happened was left unresolved. I think the lack of understanding/resolution is why I became stuck. If I’m right then merely bringing exiles to the surface won’t result in healing if there still isn’t closure.

Report comment

Hello Richard,

well, I’ve been walking with my wife for the last 15 years helping her heal from her trauma and extreme dissociation, engaging all of her ‘parts’, learning about my own, and both of us are learning to embrace all of our selves. I think you may be misunderstanding some ‘symptoms’ as ’caused’ by the ‘protectors’ when, at least from our experience, they were caused by the associated mental traits and abilities of the various ‘parts’ that were ‘exiled’ (dissociated)…but it’s hard to see that unless you have complete access…and few do outside the primary attachment figures of each person…but I do see a lot that I agree with you on…and am glad you are having an impact…

Too bad you’ll never read my comment: I think we’d have a lot in common…

Take care and best wishes to you.

Sam

Report comment

For over two decades I have loved the Gestalt therapy notion of split off parts or personalities. It has become a dolls house model I use often. The most impressive parts get to live upstairs and receive guests. The most shunned parts get relegated to the dungeon. Down there they become a bit rogue and do jailbreaks from time to time, in the middle of elegant conversations. But mostly they become such unwanted strangers occupying the house of our psyche that we project their qualities as coming from outwith us, as coming from an external “them”.

To heal means reloving the parts of us we think are shun-worthy. But this may mean reloving qualities we see in other people who remind us of those parts we do not allow in ourselves. When we allow our split off parts to come upstairs they settle in and stop being out of control or strange.

But this may mean reloving the sorts of facets that we have been taught to loathe…

such as pompousness, arrogance, know all priestliness, smugness, monsterousness, diffidence, nonchalance, servility, cocksure imperiousness, bossiness….

the traits of a psychiatrist.

We are loathing the psychiatrist for openly allowing traits in themselves that we puritans and decent morallizers disallow in ourselves. But when we do not allow certain aspects of ourselves they can take on a life of their own and leak out in escapes until we explosively become the epitome of pompousness, arrogance, know all piety in response to others, laughably even as we declare traits of pompousness and arrogance wicked.

Actually to be pompous is great fun. Children are often dressing up as pompous superheroes.

It is not how you feel that is the problem. It is your external behaviour borne of never being in touch with emotions. The unemotional are cruel externally through feeling nothing. Their splits are all in the basement. Unloved.

Report comment

I find it really problematic that Dick is conveying false information about exposure therapy. I’m a psychodynamic therapist who sometimes uses exposure techniques to help people overcome obsessive anxiety that they KNOW is irrational (in the context of the present, not the past), and it is absolutely freedom giving. I’ve been around CBT therapists as well who do good work helping people with obsessive compulsive disorder. Or course we do not want to use exposure when the person doesn’t want to do it, and doesn’t see the point. But done consensually, it is empowering. Dare I say that to throw Exposure therapy and CBT completely out is Dick’s way of exiling a part of himself?

Report comment

I’ d like to share my experience with IFS, which is really different from my understanding of it I had before.

I had sth like 8 sessions, and every time different parts came along, either to be heard or to block the access to the ones who wanted to be heard and loved.

Thanks to the patience and non judgment of the therapist, I could mimic the same attitude towards these deep unknown turmoils that I was experiencing and that I hated and did not understand.

One part especially almost broke totally my new marriage to a man I deeply love. This inside man as I called him was in fact a super bouncer whose agenda was to destroy and push away very violently the man who would come to close to me. This was one of the most painful episode of my life. Having had the IFS sessions made me encounter these different parts that I did not know, love them, accept them as part of Who I am /we are. And so one day, when I was not in session, I recognized this inside man and talked to him. I totally got what he was doing and thanked him and assured him everything was ok and that we would not get hurt or betrayed. That I would be in charge from now on and that I thanked him for his service, that he could now rest. It was the most beautiful inner dialogue I ever had and since then, he did not wake up and act crazy to push away my husband. Whenever I sense sth is worrying us, I breathe and I look at the situation calmly and I find how to arrange things peacefully. He is not in charge anymore. We built a new beautiful unity inside. They’re still all here, and I’m in command, like a maestro. Try IFS with a therapist you trust, it is a beautiful way to meet your psyche and work with it with compassion. Love heals everything !

Report comment