A new study published in Theory and Psychology brought together an interdisciplinary team of academic researchers and young mental health service users to examine the role of youth agency during routine clinical encounters in mental health emergency services. Analysis of video-recorded conversations revealed common ways clinicians in emergency services undermine young people’s sense of agency.

The authors, led by Lisa Bortolotti at the University of Birmingham, used their findings to develop a framework of recommended communication techniques for healthcare professionals to empower young patients and improve clinical outcomes.

Many people seeking mental health care describe feeling invalidated and misunderstood by service providers, which can contribute to feelings of hopelessness and helplessness and deter them from seeking future treatment. The authors describe this experience as a loss of a sense of agency:

“Agency is a person’s capacity to intervene in their surrounding physical and social environment in order to pursue their goals and interests. In a mental health crisis, goals may be health-related (e.g., improving one’s mental health). A person’s sense of agency is their perception of their agency: a person who feels helpless typically does not have a strong sense of agency.”

Young people who are struggling with their mental health may be at particular risk of feeling a loss of agency during clinical encounters. Young people may be more susceptible to feelings of insecurity and powerless in response to others involved in encounters (e.g., parents, practitioners), as inherent power imbalances are exacerbated by age and developmental stage differences. Negative stereotypes associated with young people in distress (e.g., labels such as “snowflake” and “drama queen”) may also contribute to mental health professionals forming assumptions that young people are immature or attention-seeking and trivializing their experiences.

Young people who are struggling with their mental health may be at particular risk of feeling a loss of agency during clinical encounters. Young people may be more susceptible to feelings of insecurity and powerless in response to others involved in encounters (e.g., parents, practitioners), as inherent power imbalances are exacerbated by age and developmental stage differences. Negative stereotypes associated with young people in distress (e.g., labels such as “snowflake” and “drama queen”) may also contribute to mental health professionals forming assumptions that young people are immature or attention-seeking and trivializing their experiences.

Researchers highlight the importance of young people maintaining a sense of agency during the clinical encounter as a matter of epistemic injustice:

“Epistemic injustice occurs when the subordinate party is not regarded as a credible or reliable knower by the dominant party for reasons that are irrelevant to the subordinate party’s capacities as a knower and depend rather on negative stereotypes associated with the subordinate party’s identity. As a result, the dominant party may enjoy excessive self-trust whereas the subordinate party comes to question their own self-trust.“

Suppose the practitioner (“dominant party”) asserts their control over a clinical encounter without meaningfully including the young person as an agent. In that case, the young person’s feelings of inadequacy and self-doubt will be exacerbated, and they may be deterred from seeking support in the face of a future crisis.

To explore how epistemic injustice plays out in the context of mental health emergency service encounters, an interdisciplinary research team led by Lisa Bortolotti at the University of Birmingham was formed. The team was made up of 6 academic experts from the fields of philosophy, psychology, clinical communication, and public research, and five young people (ages 17-25), each with 4-16 years of lived experience receiving mental healthcare (referred to as Youth Lived Experience Researchers; YLER).

Video recordings were taken of 19 psychosocial assessments conducted by 11 emergency department (ED) practitioners and 18 young people (ages 18-25) presenting to the ED with self-harm or suicidal ideation between September 2018 and April 2019. Practitioners included mental health nurses, doctors, social workers, and other professionals. The content of the conversations included treatment planning, risk assessment, and diagnostic evaluation. Researchers met collectively to analyze the video recordings qualitatively. One team member who is an expert in conversation analysis led the researchers in open discussion to detect patterns across recordings and to identify overarching themes. Throughout the analytic process, the YLER offered further interpretations of the data based on their own experiences.

The YLER articulated five components of agency that are essential to them but that they saw as being repeatedly undermined by practitioners during their encounters with young patients:

“(a) An agent is a subject of experience, and their perspective matters; (b) an agent can take action to change their situation by seeking help; (c) an agent may have multiple and conflicting needs and interests; (d) with adequate support, an agent can contribute to positive change; and (e) with adequate support, an agent can participate in decision making.”

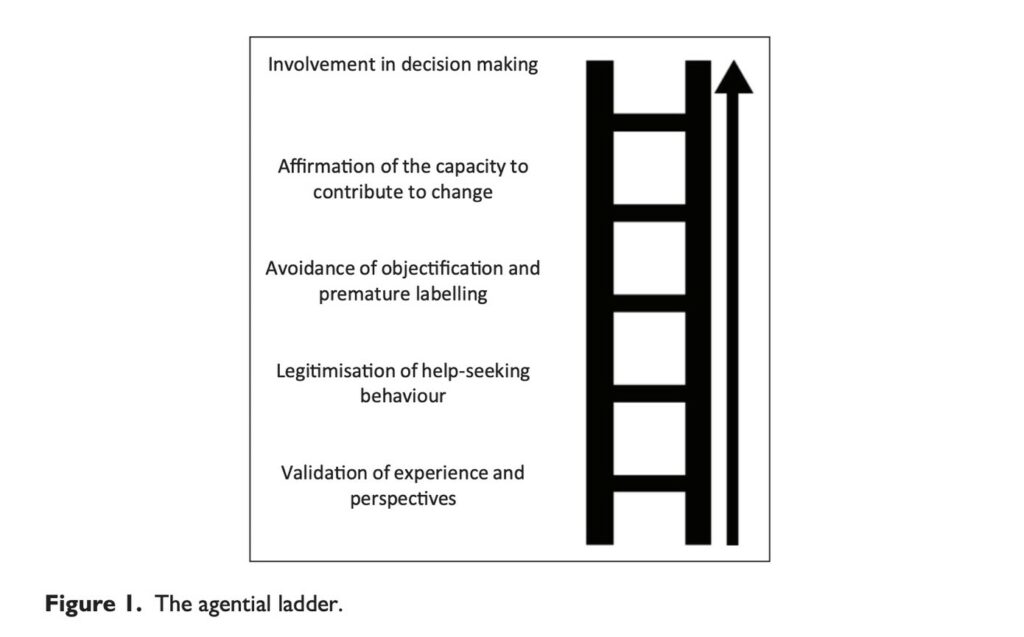

Authors integrated these components of agency to re-imagine how healthcare professionals approach crisis service encounters. They argue that professionals can and should take an “agential stance” by acknowledging young people as subjects of their own experience whose perspective matters. The authors outline five communication techniques for practitioners to use to embody this stance while interacting with their young patients.

Validating the young person’s experience

The YLER highlighted the importance of practitioners’ being attentive and empathic listeners. Rather than jumping to problem-solve or offer a “solution,” practitioners should first take the time to acknowledge a patient’s experience of distress. Across the video recordings, validation was rare. However, when even brief validations were offered during an assessment (e.g., “that’s a scary thought”), they typically led to the young person opening up more about their feelings and experiences. In contrast, when a practitioner contradicted a patient’s experience or dismissed it with a minimal response (e.g., “Right”), young people tended to disengage from the conversation or exhibit signs of increased distress.

Legitimizing the young person’s choice to seek help

Practitioners who legitimized the young person’s choices were those who communicated that the young person’s difficulties were genuine and that they had made the right decision to seek out help. Examples of delegitimizing approaches practitioners took in the videos included: regarding the young person’s distress as ingenuine, telling young people their concerns are not severe enough to justify emergency services, and failing to help a young person identify suitable avenues for support. Conversely, communication techniques that legitimize young people’s actions include commending them for seeking services (e.g., “you did exactly the right thing”) and encouraging them to do the same thing in the future.

Avoiding objectification

According to the authors, young people are objectified in the mental healthcare context when “they are seen as a category of the patient or the embodiment of a specific problem to solve.” In practice, practitioners objectify young people by only asking about their symptoms and self-harming behaviors and failing to understand their broader identity or context (e.g., family, school).

For example, one young person in the study described how previous mental healthcare providers had redescribed her experiences to fit into diagnostic categories:

YP: I don’t know. I just feel like that’s- kind of- I’m not sure, not a cop-out, but I feel like they haven’t- doctors that I’ve spoken to haven’t really bothered to like go deeper. And they’ve just thought, “She’s a young person. I’m gonna look at these symptoms. Ignore the rest. And just fit it to what I want it to be.”

Objectification can contribute to a young person’s feeling of identity loss or confusion and can negatively impact their health outcomes by leading to inappropriate treatments and mistrust of services. To avoid objectification, researchers write, practitioners should approach young people as multifaceted beings with diverse and changing needs and resist the urge for premature and superficial labeling.

Affirming the young person’s capacity to contribute to change

Video recordings illustrated multiple instances of practitioners in crisis settings failing to consider the context of the young person’s choices and actions and blaming young people for their self-harming behavior. In doing so, practitioners may trigger a sense of guilt and shame.

Authors offer an alternative “nurturing stance” that they suggest mental health practitioners take. This approach focuses on reflecting on the young person’s positive work and affirming their capacity to positively contribute to change in their future, rather than judging them or blaming them for their past actions.

Involving the young person in the decision-making process

The last communication strategy that is key to the agential stance is shared decision-making. For young people to feel a sense of agency during a clinical encounter, they should be treated as informants and collaborators during treatment planning rather than as passive sources of information. This includes practitioners asking young people for their perspectives on different treatment options. The YLER described how disempowering it can be for young people to be excluded from decision-making about their own care. Therefore, they emphasize the need for practitioners to value the young person’s perspective while still offering their own expertise and recommendations:

“It’s crucial that a young person is given the opportunity to identify the appropriate treatment for themselves. A practitioner’s role is to communicate the best solution based on their specialized knowledge, but it should be up to the young person to absorb that knowledge and choose a course of treatment that they see will best improve their life. Instead of being forced to take medication/therapy, they should feel empowered to take responsibility as it demonstrates that they have the intelligence and agency to get better. (YLER member)”

In summary, researchers offer an “agential ladder” made up of five sequential communication strategies (validate, legitimize help-seeking, avoid objectification, affirm capacity for change, and share decision-making) that can be used by mental healthcare practitioners to empower young people and protect their sense of agency during clinical encounters. Authors assert that this approach can improve therapeutic relationships and enhance clinical outcomes and that it should be explicitly taught to mental health professionals in training.

****

Bergen, C., Bortolotti, L., Tallent, K., Broome, M., Larkin, M., Temple, R., … & McCabe, R. (2022). Communication in youth mental health clinical encounters: Introducing the agential stance. Theory & Psychology, 09593543221095079. (Link)

Psyche is not clinical in the first place. Monism without psychological roots is marxism in glorious disguise. Can’t see James Hillmans rhetorics, on this site. So how can anyone here, defend psyche. You are using monistics ideologies talking about the psyche, it is useless. Clinical language based on theological rhetorics is a form of totalitarian defense of materialism. It is worse than pure satanism – to use god in defence of materialism. Monotheistics materialism is not even a christianity. It is ideology based on theology of materialism, without psyche, without god. Psyche treated as a form of science, without the idea of the psyche – this is pure psychopathy. Mental helath is a form of psychopathy. God is not clinical or medical, either psyche is. Materialism depend on psychological roots and spiritual infuences. Without non material influences – this is materialism. Marxism. We can’t say we defend psyche and at the same time still use hostile ideologies to fight with the psyche. You are using medical language talking about the psyche, it is post enlightenment insanity. Diagnosis without the idea of the psyche, is a condemnation and curse in medical disguise. This is the ego cult without psychological influences. God is real, psyche is real – the language of zombies is dead. “! You think you’re safe and alive? You’re already dead! Everybody! Him, you, you’re dead already! This whole place! Everything you see is gone! ‘ Sarah Connor, “Terminator2”.

Report comment

Though this was a very progressive and forward-lookng study, it only involved 19 recorded interviews. How much real data can you glean with only 19 interviews?

My own (limited) training in spiritual counseling included a “code” for the counselor to follow whenever he worked with someone (NOT called a “patient” in our practice). This code has existed in some form since 1950. So it’s not like no one has ever looked at this issue before. To my mind, the field of mental health is famous for its ignorance of the human experience.

The “code” and guidelines I was taught are very similar to those outlined in this article. It is really a shame that they were never embraced and adopted by “professionals” in the field of mental health.

Report comment

The problems listed in this article aren’t limited to youth or mental health emergency service providers – it’s how much of psychotherapy is conducted. And therapists give it a fancy name: “power imbalance”, which is code for “therapists knows better than the patient/client”, which speaks volumes about what’s going on in many therapists’ heads and why: an unquenchable thirst for ego gratification/grandiosity, an obsessive desire for control and need to be seen as “right” – in other words, to be seen as an “expert”. It’s professionalized psychological abuse.

And contrary to what most therapists would have people think, the solutions aren’t rocket science, as the above article offers five common sense solutions anyone can learn:

1. Recognize and accept another’s experience (validation)

2. Commend them for seeking help (legitimize)

3. Seeing the person as an individual, not as a problem to be solved (don’t objectify)

4. See people as capable of helping themselves to the extent they choose (respect their agency)

5. Let people make their own choices (quit being a know-it-all and telling them what to do)

Report comment

Great list.

Report comment

This article proves that most problems in “psychotherapy” are with the therapists themselves, most of whom don’t bother to practice the basics of helpful human relationships, which happen to be courtesy and respect, the lack of which is endemic to most “psychotherapy”.

Report comment

This article shows how easy it is for therapists to be more concerned with playing “the expert” than actually helping people.

Report comment

It has been established that the quality of relationship with the therapist is more important than their training or school of therapy

https://www.family-institute.org/behavioral-health-resources/importance-relationship-therapist

Report comment