On the Mad in America podcast this week we are sharing a special interview that’s being done as part of World Tapering Day. World Tapering Day is being held on the 4th, 5th, and 6th of November 2022 and it aims to raise global awareness of the need to safely taper psychotropic drugs. It has been organized by people with personal experience of the severe difficulties that can arise when stopping antidepressants, antipsychotics, or benzodiazepines. If you would like to find out more or participate, you can visit the website WorldTaperingDay.org where you can sign up for a range of free-to-view webinars.

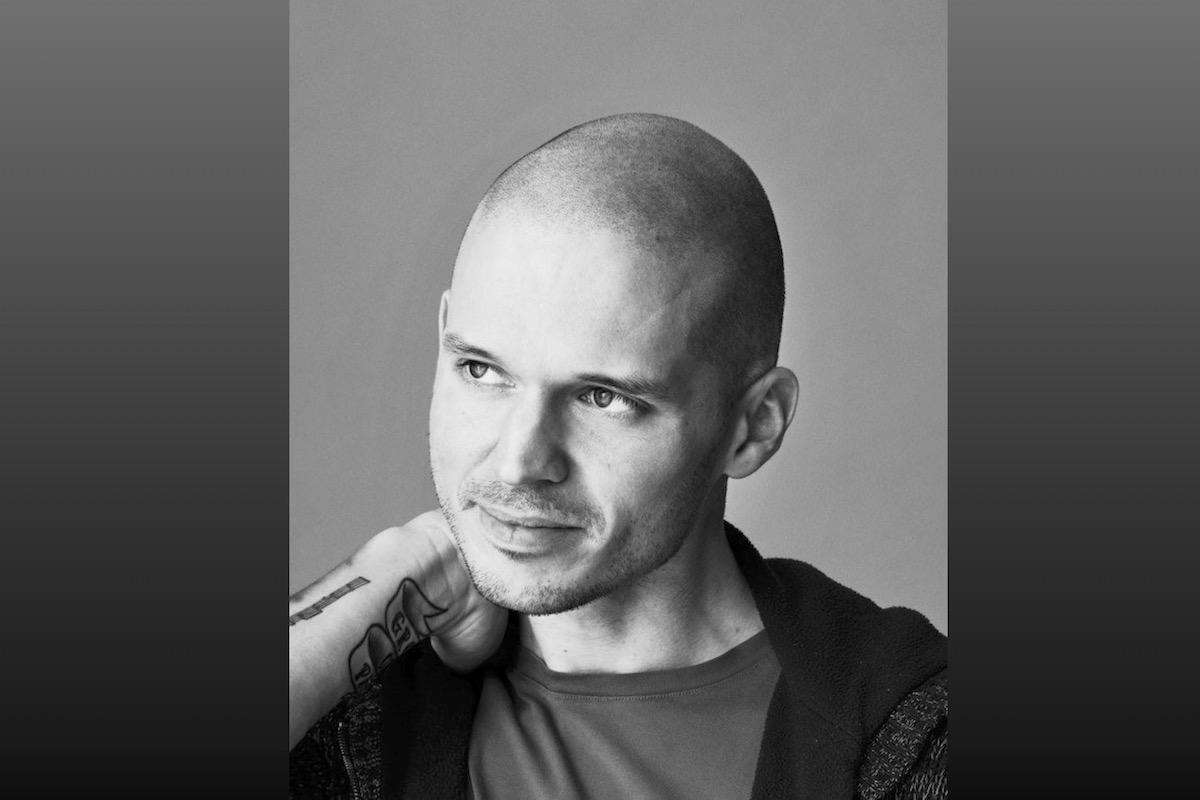

Our guest today is Anders Sørenson. Anders is a Danish clinical psychologist with a special interest in psychiatric drug withdrawal. He has undertaken research which assesses the state of guidance on psychiatric drug withdrawal. He has also paid close attention to tapering methods with the aim of identifying approaches which might make withdrawal more tolerable for people.

In addition to his research work, Anders utilizes psychotherapy in his private practice when helping people to come off the drugs and we’ll get to talk about some of that in this interview.

The transcript below has been edited for length and clarity. Listen to the audio of the interview here.

James Moore: Anders, welcome. I’m so pleased that you could join me today.

Anders Sørensen: Thank you, me too. Thanks for having me.

Moore: Could you tell us a little bit about you and how it was you came to be interested in issues around withdrawal from psychiatric drugs?

Sørensen: The long story short is that I like good science and I like studying what good science is, which is a research field in its own right. The science of science, if you may.

When you’re really interested in quality science and then dive into psychiatric research, your heart is kind of broken. It looks convincing and it looks persuasive and it’s written in a very academic and persuasive language with all the brain scans and the biological measures, the fancy words and all the theories. In reality, it is replete with assumptions and bias, especially regarding the theories we have about how psychiatric drugs work. That’s what got me into this field.

When you study the literature in this light, what happens, at least for me and some colleagues, is that we end up understanding psychiatric drugs as purely symptomatic treatment. They can be helpful for some people and some situations, preferably in acute crisis and short-term, but in a fundamentally different way than what we’re told about various biological abnormalities.

I did my bachelor’s degree back in 2014 on epigenetics, which I shouldn’t dive too much into but the idea was entitled “The Implications of Epigenetics on Psychiatric Drug Treatment.” It was aiming to debunk these basic assumptions in talking about antidepressants and antipsychotics and there being any causal relationship between any brain abnormality and the reason for intervening. It just doesn’t hold up; it is not true, and I believe we can make that argument using pure data and logic.

My next question was then, how then do psychiatric drugs work? It’s not that they don’t work, it’s that they work in a different way than we have been told. In psychology there is a concept known as emotion regulation; let’s consider the definition. Emotion regulation in psychology is defined as the processes by which individuals influence which emotions they have, when they have them and how they experience and express these emotions. Another definition is actions taken by a person to modify or change emotions in order to reduce their intensity.

Now, if we leave aside the idea of the drugs treating any biological illnesses, these concepts kind of make sense for what psychiatric drugs do. They are emotion regulation strategies, things we take to regulate our minds and our moods; they are psychoactive substances. No biological magic is happening there.

The reason this is interesting is that emotion regulation has received a lot of attention in clinical psychology because it appears that it matters how we regulate our emotions and thoughts. We know that strategies like avoidance, suppression, distraction, worrying, rumination, or isolating ourselves, all these strategies tend to correlate with psychopathology and actually can predict it. They often work here and now, but then tend to backfire in the long term, creating other problems. Whereas, strategies like acceptance, problem-solving, allowing emotions to unfold, actually listening to them, cognitive restructuring, detached mindfulness, all these fancy psychological terms, tend to correlate with low levels of psychopathology.

So I asked myself the question, what is the difference between helping people come off psychiatric drugs, which is a way of numbing the mind and artificially controlling emotions and doing what I would otherwise do as a psychologist? I concluded in my master’s thesis back in 2016 that these are largely the same. I can draw on my psychotherapeutic tools to help people come off psychiatric drugs with one major difference, which is why we’re here today, the withdrawal symptoms.

You can’t just stop and you can’t just remove drugs as a strategy because you get dependent on them. I discovered early with my first patients that they couldn’t just stop and the withdrawal reactions that they experienced were way worse, more extreme and longer lasting than what we were told. I decided to trust my patients and not so much the books because I’ve seen other things in the psychiatry books that turned out to not be true. So that set the stage for where I am now.

Moore: In 2021, you authored a paper which reviewed an important aspect of how antidepressants affect the body. We sometimes hear about brain imaging techniques, PET or SPECT scans, being used to study what is known as serotonin transporter occupancy. So, before we talk about the findings of your research, could you tell us a little bit about what serotonin transporter occupancy is and why it might be important in understanding withdrawal problems?

Sørensen: Yes, of course, because it’s the center of the main argument here. The serotonin transporter is a receptor and it’s the primary target receptor of most antidepressants. That’s what psychiatric drugs do, they occupy receptors. The brain has a function to reuptake its serotonin from the synaptic cleft and that’s completed by the serotonin transporter. So, all you need to know is that occupancy is a term for what the drugs do, they occupy receptors.

Serotonin transporter occupancy is the mechanism by which most antidepressants raise serotonin levels in the brain. Selectivity is an illusion, I should say and it’s reductionist to only look at one receptor. The first “S” in the term “SSRI, “selective,” actually is not possible. Ask anyone who studies the brain and they’ll say it’s not possible to just selectively target one receptor and then increase or decrease that, but it’s the primary biological mechanism of action. That’s why we would expect withdrawal symptoms to somewhat follow the degree to which the drug occupies this receptor.

The point is that, once we understand brain chemistry is not out of balance, but it’s actually under what is called homeostatic control, we then understand that what the drugs do to our brain chemistry is not a correction, it’s not fixing stuff. It’s actually a perturbation, which the brain is fundamentally hardwired into identifying, recognizing, and then counteracting, and that’s the theory right now for why we get withdrawal symptoms.

So, if you raise serotonin levels with the drugs, then the body reduces its sensitivity to serotonin. Similarly, if you reduce your sensitivity to dopamine using antipsychotics, the body just says “Hell no, I’ll spit out more dopamine.” So, it will always regulate in the opposite direction, regardless of how we feel about the drug.

The problem with withdrawal symptoms, like serotonin levels, is that when you reduce the drug dose, the affected levels of neurotransmitters will reduce faster than the adaptation. There is a time lag there and it’s that period of time when we’ll experience withdrawal symptoms. The body has to readapt to a lower dose and that takes time depending on how much you reduce the dose. Hence the whole idea of gradual tapering, to give the body this task in small pieces.

Moore: I was interested to read in your paper that the PET and SPECT scans that are used can’t actually tell anything about the effect of these drugs on whatever depression is in the brain, but they can act as a proxy measure for how the drugs affect the brain. Is that right?

Sørensen: Absolutely, right. I think we have plenty of evidence of that and that’s the irony of all. Depression doesn’t have anything to do with imbalances in the system, but that doesn’t change the fact that the drugs do affect serotonin levels. You can’t talk about withdrawal symptoms without talking about the clinical drug effect. This definitely is a biological effect on the brain, which means that the body adapts and this definitely has relevance for withdrawal symptoms but not so much for the clinical effect.

This adaptation, as I see it, is a fundamental thing that all long-term psychiatric drug treatment has against it. The body will eventually adapt and when you stop the drug it can create this illusion of an effect because you stop the drug and you feel worse. Is that because you got into contact with the underlying withdrawal state, or is that because the drugs work? The solution to that, which is why we are here, is gradual tapering to solve that problem.

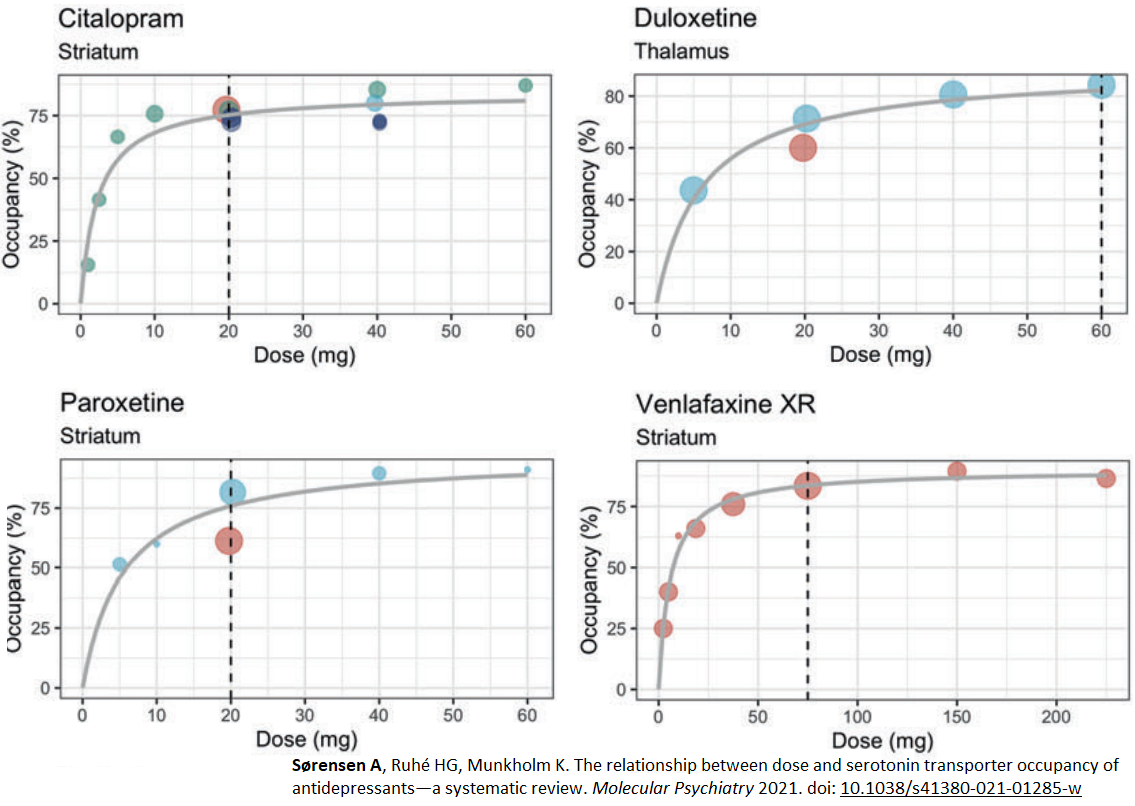

Moore: Turning to the results of your work, some of the studies you looked at showed that even a low dose of an SSRI can occupy these serotonin transporters to a great extent. So, in the paper, you give the example of fluoxetine or Prozac. The studies reviewed found that just a one-milligram dose might give an occupancy rate of between 24 and 36 percent. So, that one milligram is doing a lot of work in the brain, isn’t it?

Sørensen: Exactly, and that’s what we are trying to get people to understand. It looks absolutely absurd because that one milligram is one-tenth of the smallest pill. We also have data for Effexor (venlafaxine) which has been measured down to one-fifteenth of the smallest standard available pill. It looks absurd, you almost can’t see it when you put it on the table but it has a very high occupancy effect.

When we say that one milligram has between 24 and 36 percent occupancy of the serotonin transporter, what that means is that out of the 100 percent, out of all your serotonin transporter receptors, between 24 and 36 percent of them are occupied by one milligram and that’s the whole idea. These data show how extremely potent antidepressants are at low doses because, in fact, these aren’t low doses, and so the problem is obvious.

From looking at the resulting graphs you can see the relationship between dose and occupancy: as dose increases, occupancy increases. The biological effect on the brain does increase extremely rapidly in the lower dose range and then it plateaus. Now, the problem is obvious. Small reductions in the lower dose range will have large effects on serotonin transporter occupancy and those sudden drops in serotonin levels will increase the risk of severe withdrawal symptoms.

Moore: That’s important, isn’t it, because people listening to this will have experienced when you go to your doctor and the doctor says, “You’re on a very low dose. I don’t see any reason why it should be a problem for you to come off,” but the review work that you did explains really well why it gets so difficult for people as they get to lower doses.

Sørensen: Many people will get stuck at lower doses and it looks funny, these small dose reduction schemes. Sometimes, you can actually make some pretty dramatic reductions, if you’re on a high dose. Now, I shouldn’t put any rules up here, because some can and some can’t, but some definitely can reduce the dose in the higher dose range quite dramatically with no other consequences and few side effects, but no withdrawal symptoms.

Then at some point, you hit this plateau and then just five or 10 percent of your dose will have dramatic effects, and if you don’t know that the relationship between dose and occupancy is non-linear, that makes absolutely no sense. That’s where research comes second to the lay-people community. They’ve known this for years, maybe even decades but have kind of been laughed off by academic psychiatry. They haven’t been believed that such a small dose reduction can have a large effect and now we have the data. These are hardcore biological brain scans of biological effects, which is really good. So, the patients were right.

Moore: It is really validating, I think, for those people who know themselves that they might have had an easier time to begin with but a terrible time at some point in the lower dose range. They’ve shared this with their doctor who says, “That doesn’t make sense, because the effects should get smaller with a lower dose,” but this work proves the mechanism by which that isn’t true.

In the paper then you go on to talk about what’s called hyperbolic dose reduction, as a way of mitigating this problem. Can you tell us why a hyperbolic reduction might be preferable to a fixed reduction rate or equal percentage decreases?

Sørensen: This goes back to understanding why withdrawal symptoms occur. It’s a readaptation required in the brain. If you just stop the drug at the lowest standard available dose or even half of that, you stop the drug at a dose corresponding to very high occupancy rates and the body can’t keep up. So we’re trying to solve that problem.

The solution is quite obvious, you need to go way below the lowest dose. Sometimes, down to one-tenth or one-fifteenth of the lowest dose. Linear tapering would be, for example, reducing by five milligrams each time all the way to zero. We show that each five milligrams you take off will be a much larger reduction than the previous one.

The solution to that is what’s been called hyperbolic tapering. If you have to put some rule, which I rarely do, it means that you should reduce by some percentage of your previous dose, not of the original dose and that will mean that the dose reductions get smaller and smaller. So, hyperbolic tapering is all about making the reductions kind of fit this hyperbolic dose occupancy and it means that as you approach zero, your dose reductions need to be smaller and smaller.

That’s a way of unblocking the serotonin transporter gradually, which is what we want and it requires a hyperbolic reduction of the dose. If you reduce in the same increments, the next reduction will always correspond to a larger occupancy reduction and that’s where you’ll have problems.

Moore: Has there been any work done to rerun these PET or SPECT scans on people who have completely withdrawn to see whether any different data that arises afterwards? I am guessing no.

Sørensen: Sadly, no, we still have a long way to go. Sometimes we still have to convince people that withdrawal symptoms actually exist and that they are called withdrawal symptoms. We are allowed to call it withdrawal symptoms in the major papers now, not discontinuation symptoms, but no, that kind of research I haven’t seen.

Moore: The other part of this is for people facing withdrawal there is a significant physical challenge there but there is a psychological challenge too. You are a psychologist and work in clinic so you’ve already recognized the importance of helping people practically deal with withdrawal and aiding them with the psychological issues that arise during the process of coming off the drugs.

Could you tell us a little bit about the kind of psychological challenges that people withdrawing face and how psychological therapy might help them through those difficulties?

Sørensen: So, one thing is minimizing the withdrawal problem with hyperbolic tapering. The next thing is helping people get through withdrawal because most people cannot completely avoid withdrawal symptoms, especially in the last phase of tapering. You’ll need to learn how to get through withdrawal symptoms, how to regulate and manage them while they are there, and we have a lot of psychological methods that I find helpful.

The first question is, how do you get through withdrawal? Then the next psychological question is that we just established that the drug is a coping mechanism, nothing else. So obviously, you’ll need other strategies once off the drug. If you’re used to regulating your mind with a substance that sedates it, dampens it, creates a distance, you’ll need other strategies to prevent relapse, definitely.

So, the reason that withdrawal symptoms are a problem is that they can pull in your attention. They can capture your focus, they can steal it from other things you want to do, like socialize or enjoy things, stay focused, or sleep even. We can solve that problem psychologically.

Psychologically speaking, your attention is something you can train. You can train to be in distress and not give it your focus. It’s a very fluffy thing to try to explain, that’s why we have all sorts of experiential exercises, but the theory is you can actually learn to not give focus, not fight it, not suppress it, but detach from it. That to me is absolutely the strongest psychological friend in psychiatric drug withdrawal because you can actually learn to not pay attention to even pretty serious symptoms, and most people will find that they have a better day doing stuff, to the degree that they can do stuff.

That’s the fundamental problem, it’s difficult because your attention is constantly being pulled towards the symptoms and your distress, but it doesn’t change that you could learn it. You can discover how to be in distress and not give the distress focus. Once we understand that withdrawal symptoms are like a wound that your body knows how to heal, it will heal, but we can’t intervene. We can’t speed up the process, but we can let the wound be a wound and be engaged in other stuff. It sounds difficult, I know, but it’s possible.

We have used various experiential exercises to actually discover this, and then you will discover that withdrawal symptoms like catastrophizing thoughts or depressed feelings tend to step into the background when you focus externally. It’s very powerful to discover that mechanism. That’s what gets you through weeks, months and sometimes years of withdrawal.

Moore: In the community of people affected by this, there are some who say, “I’ve tried to accept what happened to me, the drugging and the difficulties and all the rest of it.” They try their best to coexist with it. Then there might be another group of people who say, “I can never accept what was done to me,” and fight against it every day. Is it healthy, do you think, to try and accept what we can’t change and to try and live with those difficult experiences?

Sørensen: Yes, as long as it doesn’t sound like giving up, because you’re entitled to be angry. You didn’t put yourself in the situation of getting dependent on prescription drugs. All emotions you may have are okay. Acceptance can sound like giving up, it has a negative vibe to it. Not in my opinion, it’s the opposite of fighting against what’s there and withdrawal is difficult enough already.

So, the best way through the symptoms is some degree of radical acceptance and forced mindfulness. It can remove a whole psychological layer of worries and ruminations and threat-monitoring. All the things that we do to protect ourselves but that actually end up working against us. I promise you, you won’t find anything of value in the withdrawal emotions, because it can look exactly like depression. It can look exactly like anxiety, but it’s not. The emotions are artificial, they just present themselves as very real.

Besides the correct tapering, there is an issue of helping people get through periods that feel like depression but are not depression. Normally, when you’re depressed you should figure out what you’re depressed about and do something about that. But in these exact emotions, there is absolutely nothing in there. It’s a product of adaptation.

Moore: It’s a cruel irony that many of the effects people get from coming off the drugs mimic the reasons they were prescribed the drugs in the first place. Then you go to a doctor who knows nothing about withdrawal or tapering and they say, “Well, it’s just your illness returning,” but we know that’s not the case, don’t we?

Sørensen: Yes, and that’s really my day at the office in a nutshell. Obviously, first avoiding this. Then, sometimes we can’t avoid withdrawal and sometimes, we can minimize it. Then it’s a question of going through these emotions a couple of times. That’s really strong stuff to actually have a physical and emotional experience of, feeling absolutely horrible and depressed, but experiencing that will fade and that’s what we need to help people get through.

Sadly, that happens rarely and that gets back to your definitions of withdrawal symptoms. They are often understated by doctors compared to what people who experience it say. That’s a problem because your doctor will look up guidelines and see withdrawal symptoms are something self-limiting, brief and mild, lasting maybe a couple of weeks, that’s the professional definition. This results in a lot of withdrawal reactions routinely getting misinterpreted.

Moore: We’ve talked about the fact that there is a wide range of experiences that people have when they try to stop antidepressants. Some can seem to get off without too much trouble, some have problems when they taper but they are fine afterwards but there are a group of people who seem to struggle for long periods after they’ve tapered. What is your experience of people who go on to suffer long-term problems after tapering off antidepressants?

Sørensen: That’s one of the really dark chapters of psychopharmacology that leads to permanent damage. I see it rarely but it definitely exists. Of the people I see with prolonged withdrawal symptoms, some of them may have tapered incorrectly or dropped from a dose that was too high. It’s as if the body can get stuck. Even though we try to reintroduce the drug, the damage has been done and it needs to recalibrate with time.

So, one explanation could be simply incorrect tapering, which is why we are here, teaching people how to do it correctly. Another thing I see is people experiencing very severe side effects when starting the drugs. Now, psychiatry has succeeded in telling us to just keep taking the drug and it will pass.

The reason I am saying that is that some of the people I see have been only taking the drugs for maybe weeks, maybe months, so they haven’t become that dependent on them. They tapered off the drug and these side effects kept on going. I think that’s really where it all starts, if you have severe side effects when you start the drug you can also get stuck. So, either incorrect tapering or extreme sensitivity to the drug’s adverse effects.

The problem is that we can’t know in advance. Any given person cannot know whether they are very sensitive or whether they will have problems getting on and off the drug. There is no way of predicting it, so, it’s gambling to some extent.

Moore: It is very much a gamble for people, isn’t it, because they might not know they’ve got a problem until several years into treatment. Then, when they try to stop and make a small reduction, they are in the most difficult place imaginable.

Sørensen: Yes, and they didn’t ask for that and the worst of all is that we aren’t informed about this. It’s in the science but the whole idea of having a guideline is that not every doctor or patient has to go through all the scientific literature. So, we hire some people to make a guideline condensing their research literature. That is a huge problem and it’s a huge gatekeeper for conflicts of interest because much of the data will not be in those guidelines for many reasons, meaning that we are uninformed.

It’s the saddest days at the office for me when I have to be the one explaining to people that they are actually dependent on this stuff, they can’t just stop. It can be severe for them to get off and it could take years.

Moore: You have a fairly unique perspective in having done PhD research on this and also helping people face-to-face in clinical practice. What have your experiences, both in research and in clinic, taught you about the best way to approach withdrawal from psychiatric drugs?

Sørensen: First of all, hyperbolic tapering is a must. It has to be flexible in some ways because it’s individual. These graphs measure the average, so, you can’t just go into the graph and read off the dose and calculate the degree of occupancy. So there’s a personalized and individual aspect to it.

That’s the first thing, it’s really difficult to make schemes and percentage rules. There is really just reducing, stabilizing, reducing, stabilizing, and then of course, really understanding how severe withdrawal symptoms can be, so you don’t get caught up in analyzing it and thinking this is you without the drug.

Coming off psychiatric drugs to me is more than withdrawal and chemistry, it involves other strategies. If you’re used to stopping your worries and your ruminations and your traumas with a drug, those often are going to resurface unless you have other treatments or strategies in place. So there is an aspect of learning other strategies, which to me is what psychotherapy is all about. That’s why I am here as a psychologist.

Psychotherapy is trying to answer the question, how do we regulate our minds with our minds? How do we stop worrying and ruminating without taking something to sedate the thoughts? We can do that, we have strategies available, especially from metacognitive therapy and some meditation practices on how to stop worrying. We know how to do that and that if coming off the psychiatric drugs means that your thoughts and feelings come alive again, which they often do, you’ll need new strategies.

It is also more than that. Often it involves actually changing your mindset and your beliefs around what mental illness is, away from this idea of having to take something to regulate our minds, away from the idea of pain being pathology, all these things that psychiatry has told us.

I should acknowledge and emphasize now that psychopathology is what we should call it here. It does exist, it’s just not a biological pathology in the way we’re told. It’s what it is that we’re debating, whether it’s a biological illness or it’s a reaction to something. So, changing your whole mindset around your condition, your emotional state of mind as a reaction to something that we have to figure out. Then do something about that, away from this whole idea of being faulty, broken, diseased. If you don’t want to wind up on the drug again, we need to get to these basic beliefs you have about what your emotions are and what’s wrong with you, and what’s not wrong with you. What you’re depressed about or what you’re psychotic about.

Many of my patients have never had those questions asked before in clinical care because it’s been out of the disease model. So, sometimes, coming off psychiatric drugs can be much more than just tapering the drug and I find sometimes that needs a bit more discussion.

Moore: You talked today about the physical dependence that arises because these drugs are acting on receptors in our brain, also you were talking about the psychological dependence that arises when a doctor tells us you have a broken brain and you need to rely on the drugs. So, I take that as the reason for needing a response to the physical dependence part, but also to the psychological dependence part too.

Sørensen: Exactly. It’s not free to give this message to people that you’re broken, you need this, there is a lot implied in that message. You’ll start to live up to that, making it a part of your identity and there is no way you’ll believe that you have more control over your mind when you have to regulate it with a substance. It confirms the beliefs about this being fundamentally uncontrollable. My mind is uncontrollable, it’s overwhelming, and I don’t understand my emotions.

It’ll feel better sometimes to not feel that, that could be attractive, it could be a way of calming the mind, but it’s not solving the problem long-term. So yes, we are absolutely influencing in a negative way our very basic psychological beliefs about who we are and what a mind is, what a thought is and how we can regulate it when given this medical model explanation.

Moore: Is there anything else important that we should share with listeners?

Sørensen: The conclusion or the implication is obvious. If you’ve tried coming off your antidepressants in a linear or fixed way, like using linear or fixed-dose reductions and you’ve deteriorated, which I guess you have if you’ve taken it for long periods of time, you haven’t tried actually tapering. That’s really the headline here. If you tried coming off psychiatric drugs not in a hyperbolic way, you haven’t tried tapering. The reaction you experienced may say absolutely nothing about who you are without the drug and what the drug is doing for you. That’s really important to know because people who’ve tried being in withdrawal will be scared of trying again. So it’s really important to say this is different.

Hyperbolic tapering works. We don’t have those big fancy randomized control trials yet. So, we can’t say it from the top of the evidence hierarchy yet, but from seeing this personally and from having all these indirect biological measures, I am convinced.

The perspective is bigger because we have no clue whatsoever whether long-term antidepressant treatment actually prevents relapse because 100 percent of the studies cited as evidence of long-term treatment are flawed by not considering withdrawal symptoms. Either they just stopped it from one day to another or with a very rapid tapering, meaning a couple of weeks or so. These studies are biased by withdrawal symptoms. So that’s a really shocking thing. So many people take these drugs and we don’t know whether they are actually necessary.

Moore: I just want to thank you for all the work that you’ve done and for the help that you provide to people because it’s all contributing to a rich pool of information on many aspects of withdrawal and tapering and why people struggle so much. We really need to convince many prescribers that while getting people on the drugs is very easy, getting people off them isn’t anywhere near as straightforward and needs special consideration.

Sørensen: Yes, it’s a crisis indeed for many people, and one they didn’t ask for.

****

MIA Reports are supported, in part, by a grant from The Thomas Jobe Fund.

“This adaptation, as I see it, is a fundamental thing that all long-term psychiatric drug treatment has against it. The body will eventually adapt and when you stop the drug it can create this illusion of an effect because you stop the drug and you feel worse. Is that because you got into contact with the underlying withdrawal state, or is that because the drugs work? The solution to that, which is why we are here, is gradual tapering to solve that problem.”

While there are many good points in this article, I’d address just this: Does any kind of gradual tapering really reverse the deleterious adaptation? It’s a bit glib to say so. Does reversing drug adaptation also correct the attendant alteration of bodily systems? In the case of neuropathy, it clearly does not. Endocrine dysfunction can be altered, as well, and this remains after withdrawal symptoms are overcome.

There is a desire to simplify withdrawal as a set of rules appropriate to everyone, and this may allow a disaster as in post withdrawal illness that has no known end point.

What evidence exists that establishes a percentage reduction as the safe and effective reduction? A percentage addresses only the drug and addresses nothing about the physiology of the patient.

Concerning Benzodiazepines, this article, fortunately, ignores the Heather Ashton demand that Benzo dependent people cold turkey from 0.5Mg of Diazepam to end their tapers. Even the Ashton based websites have quietly moved on.

Report comment

I want to believe that our minds are fully controllable but I’m going to need to see more research on how this idea applies to people with substance use disorders, especially ones that started in their teens, and complex childhood trauma. The “wiring” of your brain can indeed be altered and yes, neuroplasticity is also a thing but how do we teach people who has spent formative years of their lives, both behaviorally/developmentally and neurally speaking, regulating their brains with substances how to just not do that anymore. This just seems so overly simplistic. Most of these people are in situations that will probably never get significantly better because of systemic injustice – such as previous criminal records that keep them from getting jobs resulting in economic oppression with little to no hope of getting out of it. Is it really possible to teach people in these situations to “rise above”?

I’m not saying that medication is the answer either (let’s face it, it starts with ending poverty) but I am saying that you can understand why some people need to numb rather than exercise their emotional regulation muscles because it might actually not be possible being that the level of treatment that a person would need is just not available. Maybe if we had inpatient facilities that did real therapy for a year It would give some people the space to actually exercise those muscles but most people in these situations are not living in a bubble where they get to just distance themselves from their hardships, both internal and external. Sometimes The numbness the medication provides them helps them to function because they have no space to build those skills. I guess when I’m trying to say here is that all that stuff above sounds great if you actually have access to real therapy. But most people don’t so I don’t really know how useful this is for the large majority of people in this country.

Report comment

I’m not saying that medication is the answer either (let’s face it, it starts with ending poverty)

Ask Lawrence Taylor! (That was a joke. So is this:) Ask 90 percent of professional athletes. They seem quite capable of drug addiction as millionaires. Addiction is no respecter of persons

AA/NA/CA/Alanon are free and have helped millions.

Report comment

Exactly how low is a lower dose on diaz. I’ve been cutting from 19mg to 7mg and its now things are harder and getting worse.

Report comment