In June, Joanna Moncrieff and others had appeared to put the final dagger into the low serotonin theory of depression (the so-called “chemical imbalance” theory). They reviewed fifty years of research into the theory and found no good evidence to support it. Many prominent psychiatrists even responded by noting that this was nothing new; that hypothesis had been put to bed long ago.

But like a ghost that just won’t disappear, a new study claims to have “clear evidence” that low serotonin is linked to depression. In The Guardian, the lead authors touted the breakthrough nature of their finding:

“This is the first direct evidence that the release of serotonin is blunted in the brains of people with depression,” said Prof Oliver Howes, a consultant psychiatrist based at Imperial College and King’s College London, and a co-author. “People have been debating this question for 60 years, but it’s all been based on indirect measures. So this is a really important step.”

This is a statement, once the study data is analyzed, that can best be described as having been plucked from thin air. Or, in science terms, plucked from a lone data point arising from a depressed patient that stood in contradiction to the rest of the data that failed to find any serotonin abnormalities in the 11 depressed patients. The one outlier is being used to falsely claim that the release of serotonin is blunted in the brains of people with depression, as though that were an abnormality characteristic of the disorder. (If you include five additional depressed patients with Parkinson’s disease, then you can say that the researchers relied on two data points—from a group of 16 depressed patients—to make their false claim.)

The Researchers’ Hypotheses

There were three groups enrolled into in the study. There were 12 patients with a diagnosis of major depression, five patients with Parkinson’s disease who also had a diagnosis of major depression, and 20 healthy controls. All 17 in the two depression groups were suffering a current episode of depression, and had not been exposed to an antidepressant in the previous six months. However, the researchers reported data for only 11 of the depressed patients without Parkinson’s disease since the measurement for one of the patients was seen as unreliable.

The researchers had three hypotheses:

- People with depression would have lower serotonin at baseline than healthy controls.

- People with major depressive disorder would have smaller change in serotonin levels after being dosed with an amphetamine.

- Both baseline serotonin and change in serotonin levels after amphetamine dosing would be related to the severity of depression.

Hypothesis 1

This first hypothesis is the one most relevant to the bottom-line question: do people with depression have lower serotonin levels than people without depression?

To test this, the researchers conducted a PET scan on the brains of people with depression and healthy controls. They determined that both the depression group and the control groups had similar serotonin levels, and both groups were consistent with “healthy” levels, which is what previous studies had found. The authors wrote:

“The regional [serotonin] distribution for both groups was consistent with previous reports for healthy individuals with high binding across cortical areas.”

The researchers then ran a bunch of additional statistical tests on this same data (tests to include other factors, such as age, and then breaking the data down into specific regions and re-running the tests—a controversial statistical process known as p-hacking because it increases the likelihood of finding a statistically significant result by chance). Even after all this, the researchers found that the depression group and the healthy control group continued to have serotonin levels which were no different, except for one slight average difference in one brain region (the temporal cortex). Even in this area, the data shows an almost complete overlap between the two groups.

Conclusion number one: There was no difference in serotonin levels between those with depression and those without. Their first hypothesis was demonstrated to be false.

Hypothesis 2

The second element of the study was a test to see whether a dose of amphetamine, which is known to trigger the release of serotonin, would produce less of a response in depressed patients than in the controls.

The researchers dosed all participants with 0.5 mg/kg of d-amphetamine, and measured how much, on average, each group’s levels of serotonin changed. This was done by measuring serotonin binding potential in the frontal cortex, to estimate serotonin release capacity.

They found a statistically significant effect: on average, the healthy control group’s serotonin levels changed more than the serotonin levels of those with a diagnosis of major depression after being dosed with an amphetamine. This was the result that prompted the researchers to write that their study “provides clear evidence for dysfunctional serotonergic neurotransmission in depression by demonstrating a reduced 5-HT release capacity in patients undergoing a major depressive episode.”

There was in fact a wide variation in serotonin release in both the depressed patients and the controls. And if the serotonin response for each of the individuals is plotted out on a graph, as was done in the paper, it immediately becomes apparent that the “statistically significant” effect arises from two individuals: one in the depressed group without Parkinson’s, and one in the depressed group with Parkinson’s.

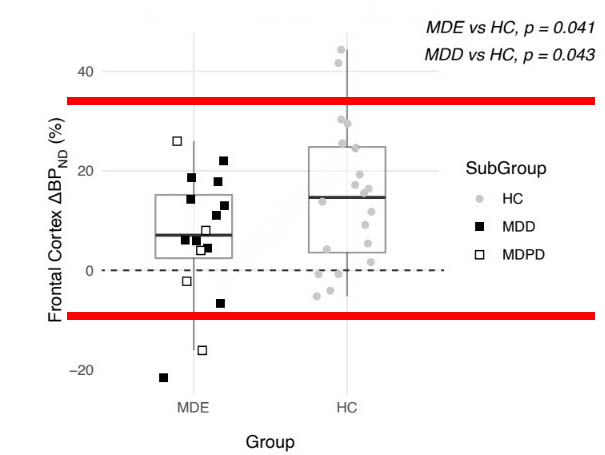

In the chart below (from the study publication, red bars added), the depression group scores are on the left, while the control group scores are on the right. The black boxes in the depression group are for those without Parkinson’s; the white boxes for those with Parkinson’s.

As can be seen, there are two outliers (one black box and one white box), and except for those two, every depressed person’s score, detailing how much their serotonin levels changed, overlaps with a healthy person’s score.

Since Parkinson’s disease is an obvious confounder, there is only one outlier in the depressed group, out of 11.

The researchers, as they reported their results, ignored this fact. Instead, they calculated the mean change in serotonin release scores for the 20 healthy controls and 16 depressed patients, and concluded that there was a slight “statistically significant” difference (p value = .041). Without the one outlier, this statistically significant finding would have vanished.

Such is the data related to hypothesis number two. And here is the relevant conclusion to draw: In 10 of 11 depressed patients without Parkinson’s, their serotonin release scores overlapped with those of the healthy controls, and thus were in a normal range. Four out of five in the Parkinson’s group were within this same normal range.

Hypothesis 3

To test their third hypothesis, the researchers ran an analysis to test whether serotonin levels were related to the severity of depression, measured by the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D), in both those with depression and those with depression and Parkinson’s disease. They found that severity of depression across both groups was not related at all to levels of serotonin.

Then they ran a similar analysis to test whether the change in serotonin levels in response to the amphetamine dosing was related to the severity of depression. They found that severity of depression was not related to the change in levels of serotonin either.

“There was no significant correlation between HAM-D depression scores and baseline [serotonin],” the researchers wrote. They added, “There were no statistically significant associations between HAM-D depression scores and [change in serotonin].”

Thus, their third hypothesis—that serotonin levels or change in serotonin would be related to depression severity—was also proven false.

They write, “We found no relationship between the severity of depression (as assessed by a HAM-D scale) and the magnitude of induced 5-HT release. At this stage we have no explanation for the lack of such relationship.”

Study Biases

The study was published in Biological Psychiatry and was led by David Erritzoe at Imperial College, London. Several other researchers unaffiliated with the study quickly pointed out several flaws in the study, starting with the fact that it was quite tiny, which increases the likelihood that any finding is due to chance. In a Twitter thread, researcher Eiko Fried compared the study to a presidential poll. Would you trust a poll of 37 people (31 male) to estimate who is most likely to win a presidential election? There is a reason polls try to reach a quorum of several thousand and a representative sample of the whole population.

In addition, 14 of the 17 in the depression group—and 17 of the 20 in the health control group—were male. The inclusion of only three women in the depression group (though women are more likely to be diagnosed with depression), the inclusion of five people with Parkinson’s disease (which could create a different neurobiological effect), the inclusion of two people taking a drug for Parkinson’s (which could create larger brain chemistry changes), and the fact that antidepressants had been used by six people in the past (which could have led to long-lasting brain adaptations) are all significant confounding factors.

It is also worth noting that the study was paid for by Imanova Ltd (now Invicro), whose profit is dependent on demonstrating the success of imaging techniques, such as PET, for “drug and diagnostic development.” In an acknowledgment, the researchers express appreciation for the work of the company’s employees “for their excellent technical support.” It is unclear how much input the company had in developing the study, conducting the analysis, and writing the paper.

The bottom line

Here is the conclusion that can be drawn from the data. Two of the three hypotheses failed completely, and while the third hypotheses led to a “statistically significant” finding, individual patient data showed that serotonin release in 10 of 11 depressed patients—those without Parkinson’s disease—was normal. The study confirmed that there was no abnormality in serotonin levels in depressed patients; it confirmed that there was no association between serotonin levels and severity of depression; and it confirmed that serotonin release in response to an injection of amphetamine was normal in all but one patient.

The researchers simply had one data point in their study that fell outside the norm for depressed patients without Parkinson’s disease, and yet they used that data point to claim that their study “provides an invaluable paradigm for the investigation of the pathophysiology and treatment of depressive disorders, and other conditions characterised by disturbed serotonergic neurotransmission.”

Such is how a zombie claim in psychiatric research is raised from the dead.

I really enjoyed this excellent analysis.

Report comment

As a study of Guardian science correspondents it confirms the hypothesis that they know little of science and tend to rewire the press release, maybe asking for a counter opinion but not examining it too closely.

Report comment

After my first try at having to follow how such pretense is put forth, I rather went to something else. Then read it again, and got through it, but along the line, maybe half way [hopefully] one does start to feel like something is weighing down on one, and this made me wonder to what degree and/or whether having to read yet another expose on this redundant corruption leads to depression. Anger, Confusion, ODD…..

And yet, if you read it, and can follow it, you learn something you wouldn’t have if you believe depression, anger, confusion, ODD etc. are “diseases.”

That is just SO NICE of these amazing authorities [Prof Oliver Howes, a consultant psychiatrist based at Imperial College and King’s College London, and a co-author] to teach us this. It may make you think that it’s making you sick having to decipher how they have you going round in circles, lead you into disarray or are simply lying to you, but in the end you’ll learn that you aren’t sick at all…..

Apparently [Prof] Howes has a whole list of conclusions quite possibly as warped ready for deciphering. https://www.kcl.ac.uk/people/oliver-howes Quite a smorgasborg: Treatment resistance to [schizophrenia] treatment that has to be listed as being based on hypothesis.

“Direct evidence for a link,” this to make you know they aren’t working with ‘indirect” evidence when searching for a link that for how many years has never really turned up. That from the title of the Guardian article: “Study finds first direct evidence of a link between low serotonin and depression.”

And the excellence of the research is highlighted by failing to list how many times already this “first direct evidence” has been found for yet again the “first” time. Evidently the second time they found this first direct link just wasn’t enough. And at what negative location did they start counting to consistently end up at positive one again? If they tried six times for the first to emerge, they started at negative five, you see….. then comes investigating what this link listed as direct really links up to…..

This is really ground breaking though, as institutions go, I’m looking forward to seeing the building built to house their future investigations of yet another first direct evidence, it would be quite miraculous would they have enough legroom to work this out, and once the building is built, and they give up, which is quite reasonable would one conclude the eventually of such, given evidence, then there’s this empty building. Maybe all the homeless people that were supposed to be fixed by this groundbreaking cure yet to be found, maybe they can have a home, right there, and prove there are other ways.

Report comment

The level of nonsense going on here:

“Study finds first direct evidence of a link between low serotonin and depression”

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2022/nov/05/study-finds-first-evidence-of-link-between-low-serotonin-levels-and-depression

To begin with, if they are now finding the first direct link to the serotonin hypothesis, isn’t this after serotonin re-uptake inhibitors have been FDA approved for how many years? Even for a direct link (rather than proof, which is isn’t, it’s only listed as a “direct” perception from those looking for a link) it’s a bit late isn’t it?

Beyond that those “medications” don’t increase serotonin, they do that for awhile in the beginning, then the brain stops producing as much (along with a host of other side effects) and you have less serotonin.

Thus, if that link was direct, and true, then everyone who has been on such anti-depressants beyond the initial transition period needs to get off of them, or they will get depressed.

What are they really saying, that actually they are lying to you: less than normal serotonin is good for you, and that is what prevents depression (along with more than normal), and anti-depressants do both, but they can’t tell you that. So in reality, you need to be lied to, and that will decrease your depression? It’s all about ideology, the more of a lie it is the more fantastic it seems, and it’s this fantastic quality that beats depression!

You have to PURSUE happiness, if you weren’t being lied to, you would have found [attained] it and cease to pursue….

Report comment

Well, Well, Well… another study where the researcher determines the results before the results come in and then interprets the results in accordance with his or her own bias. But, then, I heard a study reported through the tv media that stated “picking one’s nose” leads to alzheimers. This is modern medical science today. I realize that I am being sarcastic, but I think it might be high time, we humans stop basing our faith in medical and psychiatric science for our health and go back to good ol’ common sense. Could it be that our grandmas and great-grandmas knew more than present doctors and medical researchers, etc.? Thank you.

Report comment

Good Grief…this is an episode of “Election Deniers & Psychiatric Alternative Facts In Space” streaming on the R/Q/APA/Pharma network.

It’s dying…let it die quicker so fewer people are recruited, hurt, or killed.

Report comment

Thank you for this important article, Peter. I wish everyone duped by this “study” would read it.

Report comment

Thank you Peter, I like the Heading.

Report comment

It would make a great B movie, though-“The Return of the Serotonin Zombies…”

Report comment

“You thought it was dead and buried…

But you were WRONG!

It’s BACK and it’s COMING FOR YOU!

The LOW SEROTONIN THEORY! It’s killed before, it’s died and come back to life, and now it’s dead and can no longer be killed!

THE SEROTONIN ZOMBIE! Coming soon to a psychiatric office near you!”

Report comment

They ignored the fact that depressed patients may have low Vitamin D and that can decrease serotonin.

Report comment