Many mental healthcare professionals are unaware of the racist foundations of the fields of psychology and psychiatry. A new perspective piece in Psychological Science draws attention to how the mental health field perpetuates anti-Black racism and mass incarceration through unethical research practices and agendas and epistemic violence.

The authors, Evan Auguste, Molly Bowdring, Steven W. Kasparek, Jeanne McPhee, Alexandra R. Tabachnick, Irene Tung, and Chardeé A. Galán, with the Scholars for Elevating Equity and Diversity (SEED), are social scientists in the United States intent on drawing on diverse lived experiences to create more equitable research and practice. In correspondence with Mad in America, the corresponding author Steven W. Kasparek from Harvard University, stated:

“This work is about holding a mirror to ourselves and the field of psychology. We hope to facilitate critical discussions of the ways in which psychological research and practice has perpetrated immense harm against Black people and communities. We firmly believe that any path forward toward greater justice and equity must include recognition and understanding of the past, including how this field was, and in many ways continues to be, weaponized against Black people. Only then can we undertake the very urgent and necessary work of reshaping our scientific practices and their applications in the service of elevating the voices and experiences of Black people and communities. The ultimate goal is to co-create a psychological science and practice that build on Black traditions of radical resistance and care to improve the lives and experiences of Black communities.”

Psychology and community support have the power to potentially help alleviate some of the stressors of everyday racism, whether it be due to police brutality or suicidality. However, this power is meaningless if it does not wrestle and reckon with its racist roots.

Psychology and community support have the power to potentially help alleviate some of the stressors of everyday racism, whether it be due to police brutality or suicidality. However, this power is meaningless if it does not wrestle and reckon with its racist roots.

The authors begin their paper with a quote from Frantz Fanon:

“Psychiatry is an auxiliary of the police.”

The introduction serves to highlight how mental healthcare has not only failed Black people but is guilty of surveilling and attempting to control anyone who is deemed “abnormal” or “other,” with Black people often bearing the brunt of this surveillance.

The authors discuss the ways that the American Psychological Association knowingly perpetuates harm and mass incarceration despite current and past calls for change from Black leaders and scholars like Fanon and Martin Luther King Jr. Instead of answering this call, the field has deliberately looked the other way—reproducing, reinforcing, and adopting “stereotypical and deficit-based perspectives concerning Black people.” The authors remind mental healthcare professionals that they all share a unique responsibility in redefining and reforming the system.

The authors discuss the ways that the American Psychological Association knowingly perpetuates harm and mass incarceration despite current and past calls for change from Black leaders and scholars like Fanon and Martin Luther King Jr. Instead of answering this call, the field has deliberately looked the other way—reproducing, reinforcing, and adopting “stereotypical and deficit-based perspectives concerning Black people.” The authors remind mental healthcare professionals that they all share a unique responsibility in redefining and reforming the system.

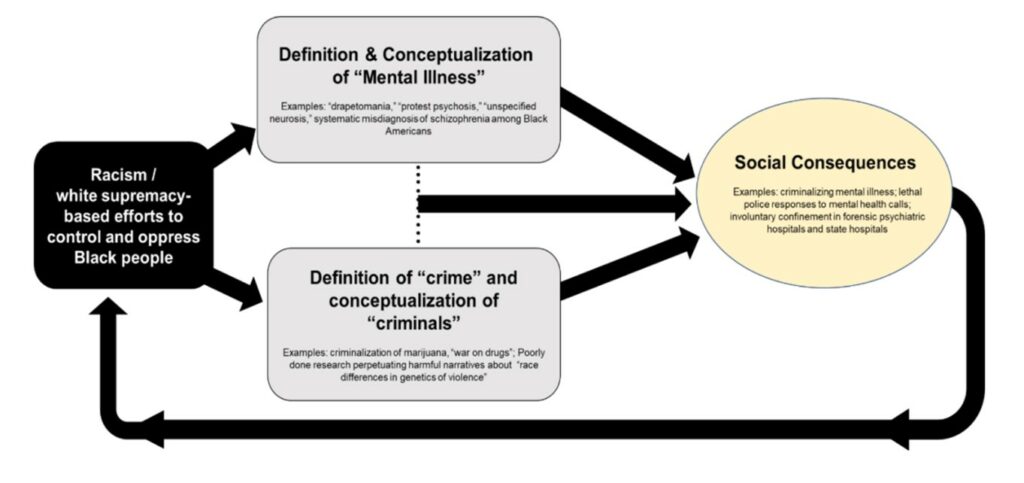

After framing the piece, the authors provide a brief history of anti-Blackness in psychology and psychiatry. Indeed, the perceived inferiority of Black people was codified in the psychological mainstream by famous eugenicist psychologists. The racism that became rooted in psychological science led to the mass incarceration and sterilization of Black people for diagnoses that pathologized protesting and “the uncontrollable desire to run away from a White master.”

Today “even when Black and White people present with similar symptoms, Black people are significantly more likely to be diagnosed with psychotic disorders while White people are more likely to be diagnosed with mood disorders.” What is more, when Black people do exhibit ‘Mad’ behaviors, they are more likely to be met with police intervention than White people, which can be deadly and have significant mental health effects post-police intervention.

“Police involvement in mental health response puts individuals at risk of physical violence via excessive use of force and, at worst, heinously results in the death of those individuals,” the authors write. “Shockingly, no less than a quarter of fatal police shootings are of individuals with mental illness, with some estimates suggesting up to 58%.”

The APA tried to take some ownership of the history of racism in the field with an apology issued in 2021. Still, the authors are unconvinced by the authenticity of the apology. Despite the APA’s most recent report on combatting racism in psychology, the authors ask whether the APA is willing to disintegrate parts of its foundation actually to affect meaningful change. In fact, the Association of Black Psychologists [ABPsi] denied the apology statement outright, recognizing that the harm will continue and stating that the APA ought not to be absolved without doing the real work to stop the killing of Black people in the United States.

The authors spend the rest of the paper outlining what “real work” is and what it ought to look like.

First and foremost is a prioritization of community-based systems of mental health intervention over police involvement. Psychologists can advance this goal, argue the authors, by pushing for reparations for Black people.

Next, a considerable amount of the paper is spent speaking to the epistemic and physical violence and systemic exclusion that has been done to Black people by White researchers. For instance, research on biological determinants of criminality serves to blame Black people for the consequences of oppression and confirm racist stereotypes and biased preconceptions that link Blackness to violence, delinquency, aggression, and drug use. This, in turn, is used to justify and enable mass incarceration.

“Another example of psychological science failing to debunk—or even actively perpetuating racist stereotypes—with downstream consequences many studies have sought to link Blackness with elevated rates of drug use and drug dealing. However, empirical evidence indicates that Black people are no more—and in many cases less—likely to deal or use drugs compared with non-Hispanic white people, a trend that has been consistent since the late 1970s.”

Lastly, psychologists can begin to rectify their wrongs by intentionally publishing Black researchers in high-impact journals. Black scientists continue to be silenced by the American Psychological Association and the American Psychiatric Association, the researchers argue, and there must be attempts made to ensure that research done on Black experiences is revered in the way White research is. This problem is also resolved by improving and diversifying syllabi to elevate Black authorship and educate budding psychologists on the historical maltreatment of Black people.

“Among approximately 26,000 publications sampled from the 1970s to 2010s in cognitive, developmental, and social psychology…only 5% of publications highlighted race at all,” the authors write. “A startlingly small minority (5%) of editors in chief were people of color, and 93% of manuscripts were edited by White editors. More shockingly is their finding that greater proportions of White editorial board members predicted fewer publications that highlighted race being accepted.”

The authors hope that the above recommendations inspire both discussion and action in combatting anti-Blackness in psychology.” The authors finish with a single sentiment:

“Let’s all get to work.”

****

Auguste, E., Bowdring, M., Kasparek, S. W., McPhee, J., Tabachnick, A., & Tung, I. (2022). Psychology’s Contributions to Anti-Blackness in the United States within Psychological Research, Criminal Justice, and Mental Health. (Link)

Please do not merely point out the psychologists, social workers, and other “mental health professionals,” systemic crimes against the black people, as their systemic crimes against the Native Americans is truly appalling, as well.

Actually, I consider their systemic and historic crimes against all people – of all colors – appalling.

Report comment

Removed for moderation.

Report comment