In the current debates about antidepressant withdrawal, it seems there are two sides—and no middle. On one side there’s psychiatry, particularly academic psychiatry, minimizing the problem. And on the other, psychologists and Mad in America authors and readers, declaring a near emergency. Every new essay prompts yet more objections from the other camp. Examples: from psychiatry, articles led by Juahar, Jha, Nutt; and many psychiatrists’ responses to Moncrieff et al’s review on serotonin (sample). On the other side of the gulf we hear Davies, Read, Hengartner, and many authors on Mad in America (sample).

Reading these presentations, one can hear anger at the others’ ideas, and anger at not being heard. One can hear pain, for suffering not recognized, and some personal affront as well. And one can hear fear, particularly fear that the other side is doing harm. Thence comes blame, which leads to more of all these feelings and interpretations.

I’d like to present a sort of middle ground, where the views of both sides are respected, and understood to have origins in wanting to help people and reduce suffering. If I’m criticized roughly equally by both sides—which I expect—at least I’ll have succeeded in presenting a not-so-visible part of the geography. However, I recognize that for some, any speech about this issue may simply arouse more harsh feelings, which I regret. Overall, I hope to contribute something useful.

I’d like to present a sort of middle ground, where the views of both sides are respected, and understood to have origins in wanting to help people and reduce suffering. If I’m criticized roughly equally by both sides—which I expect—at least I’ll have succeeded in presenting a not-so-visible part of the geography. However, I recognize that for some, any speech about this issue may simply arouse more harsh feelings, which I regret. Overall, I hope to contribute something useful.

This first essay in this three-part series looks at the question “How common is antidepressant withdrawal?” The second presents some of the challenges a prescriber faces when an antidepressant is being considered, and some partial solutions. The third asks “Why do some people, on the same dose of the same medication for the same duration, have severe withdrawal symptoms, while others have little or none?” and offers a hypothesis.

First, then…

How Common Is Antidepressant Withdrawal?

One well-known academic psychiatrist estimated that severe withdrawal symptoms happen to about “1 to 2 percent” of people stopping their antidepressants. By contrast, an oft-cited survey by Davies and Read suggested that the rate is about 50%. Who is closer to the truth?

This important question is finally being examined more closely. Unfortunately, and ironically, given that antidepressants have been in widespread use for over 20 years, psychiatry has not done the studies needed to answer this key question. This notable gap has raised some suspicion that the necessary research has not merely been overlooked but deliberately avoided. Pharmaceutical companies, exerting their influence on academic psychiatry through lucrative honoraria and advisory board payments, have clearly played a role in how antidepressant risks have been presented.

Also unfortunate: in the absence of data to help estimate the frequency of severe withdrawal symptoms, the divide in opinion about this frequency has been increasing. At minimum, and very understandably, patients feel they’ve been ignored, misunderstood, and too easily dismissed. They’ve not been listened to. Their more complex and debilitating withdrawal symptoms have been regarded as a return of their own symptoms. Their protests to the contrary have even been seen as indications of a personality disorder. Really? Yes, sadly, I recently heard a third-year resident in psychiatry dismiss concerns about antidepressant withdrawal in just this way. So no wonder patients and their sympathetic professionals, when they get a chance to speak out, feel a need to speak loudly.

The response from psychiatry ought to be to listen, to acknowledge, and to make it clear: “you are heard.” Indeed, psychiatry should go on: “These are understandable concerns about antidepressants. Your frustration is also completely understandable. We regret having seemed to be deaf to your experience. We hear you now and we are trying to figure out how to change our practices accordingly. At minimum, we will place more emphasis on the risk of antidepressant withdrawal symptoms when discussing treatment options for depression with patients.”

Only after patients and their representatives feel fully heard and understood should psychiatry offer anything that might be construed as rebuttal, e.g. “withdrawal is not as common as some have claimed.” That response is insensitive if someone is trying to explain their beliefs that severe withdrawal is a major, poorly recognized problem.

As you can gather, I’m trying to avoid making that same mistake right now. Because I can hear the frustration. I can understand the anger at being ignored and misunderstood—and even silenced, because psychiatry has access to multiple forums to present its views where patients do not. Thus, I am not surprised to see the people of SurvivingAntidepressants.org rise up and help create and sponsor a professionally produced movie that protests patients’ treatment by psychiatrists (Medicating Normal). This movie is yet another indication of needed changes in psychiatry. One of those changes is to more fully acknowledge the risks of antidepressant withdrawal.

Estimating the Incidence of Withdrawal

Which brings us back to the question “How many people have severe withdrawal symptoms when their antidepressant is stopped?” Don’t forget: I agree with the view that the answer is “many more than psychiatry thought.”

Of course, the answer is “it depends,” including: which antidepressant, as they differ in their rates of causing withdrawal on discontinuation; duration of antidepressant treatment, with shorter exposure less likely but still capable of causing withdrawal; which people, because some seem more vulnerable than others, as I emphasize in the third of this three-part set of essays; and, most of all, which definition of “withdrawal” is being used.

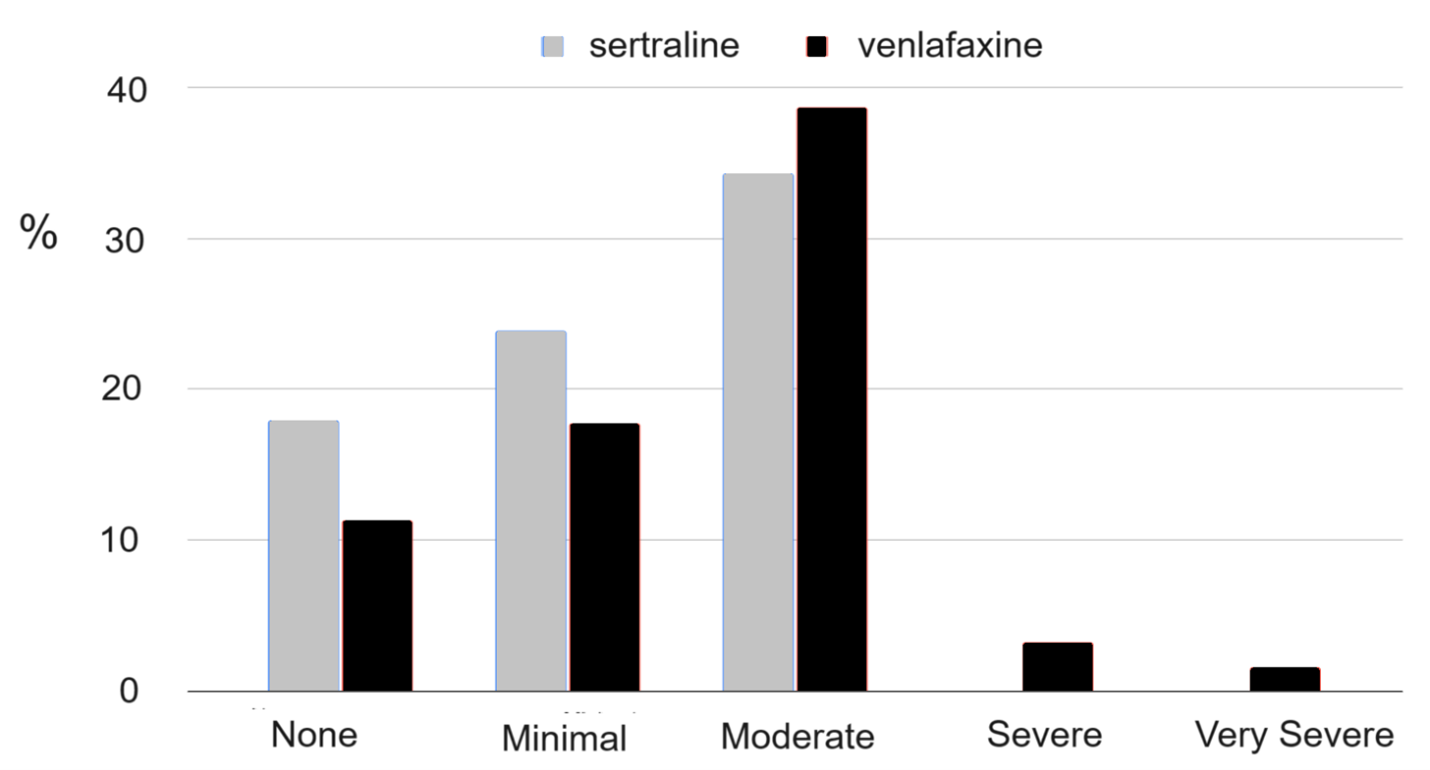

No single number accurately presents the whole picture of withdrawal. Better would be a graph, such as this one using data from a 2005 study, showing the percentage of participants experiencing various degrees of withdrawal:

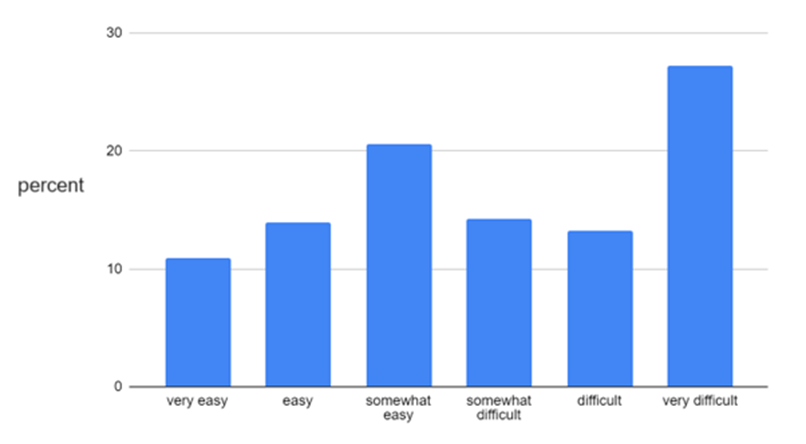

Or this one, from an international patient survey:

In another study, on a 0-10 scale where 10 scale represents life-threatening withdrawal symptoms, British General Practitioners (GPs) estimated that the percentage of their patients who experienced any withdrawal was between 20 to 40%. Their psychiatrist colleagues’ estimates were higher, around 50%. But both groups offered a wide range of estimates: the GPs, from 1% to 100%! These providers were also asked to indicate the average severity of withdrawal they observed. The average was around 4 but varied from 2 to 6; and the psychiatrists estimated an average of 5, ranging from 3 to 7.

For another perspective, our research team looked in our health system’s medical records for patients who had been on an antidepressant for at least six months and then stopped. We found that 90% did not receive the lowest available dose of their medication before it was discontinued (other records indicated that these patients were still in care in our system). If they had been carefully tapered, they would have received a new prescription for the lowest available dose, because we selected only those who had all been on a higher dose before stopping. Some of these patients likely had withdrawal symptoms that they somehow managed on their own. All we know is that they did not come back to their prescriber and receive a lower dose to facilitate tapering. These results are thus consistent with the first of the two graphs above: severe or very severe withdrawal symptoms—enough to prompt a return to the patient’s prescriber for help—were not common.

Yet people who have experienced severe antidepressant withdrawal will rightly object that studies like these fail to capture what it’s like to have awful, life-limiting symptoms. In addition, these studies also miss the many patients who resumed their antidepressant because of severe withdrawal symptoms, or because they thought, or were told, that they were relapsing into their previous illness.

What to Tell Patients, and What They Will Hear

What then should a prescriber say to their patient about the risk of withdrawal, when an antidepressant is being considered? One percent, or 50 percent? How about “when this medication is stopped, withdrawal symptoms occur about half the time. Those symptoms can be reduced or avoided entirely by slowly tapering off, but even with that, at least 1 or 2%—1 or 2 people in 100—will have severe withdrawal symptoms that require careful tapering over a year or more.”

Will people really choose to take an antidepressant, hearing that? In my experience, these kinds of warnings have widely differing effects. For example, if John’s friend just had a great response to fluoxetine, John may come in hoping to leave with a prescription for it and are not seem very concerned with the risk side. Conversely, if Sara’s relative had a very bad experience stopping an antidepressant, Sara is likely to be hesitant to start one. In that context, even a number smaller than 1% might be still arouse enough concern to steer her away from choosing an antidepressant. I’ve had patients decline lamotrigine after hearing of its 1-in-2000 risk of severe rash, saying “ah, but I’d be that one, doc.’”

My point: while we don’t have a precise figure for the number of people experiencing antidepressant withdrawal, prescribers can still offer a clear warning; and for many people, a more precise figure would not change their decision-making much.

The Context: Alternative Treatments

Even if the problem of withdrawal is presented very clearly, patients will hear that risk in the context of the availability of alternatives. For example, suppose psychotherapy is not a realistic option: e.g. when insurance coverage is limited; or few therapists are taking new clients; or serial co-pays pose a financial burden. Suppose exercise is constrained by co-morbidities; and behavioral activation is unrealistic due to life circumstances; and peer and community support is limited; and fish oil is not regarded as a sufficiently robust intervention. Under these circumstances, a patient might hear the antidepressant risk message but not strongly incorporate it into their decision-making: the cognitive dissonance between “antidepressants are your most accessible option” and “antidepressants can cause severe withdrawal” could force the latter idea to be downplayed or dismissed.

Thus, antidepressants’ benefit/risk ratio might look quite different if alternative treatments were more accessible and affordable. And for psychotherapy, that advance has occurred. Remote therapy via the internet became routine during the COVID-19 epidemic. But it may still be too expensive for many people.

Fortunately, randomized trials suggest that an online version of cognitive behavioral therapy developed by Australia’s National Health Service (MoodGym) is nearly as effective as a live therapist, if the program is offered with weekly text messaging support. (Without that support, completion rates are low, but the program is still helpful.) In addition, an online version of behavioral activation therapy (Moodivate) now has a randomized trial showing efficacy equal to an online CBT program.

Conclusion

What percentage of patients experience antidepressant withdrawal? “It depends,” especially on the definitions used. In the next essay, I’ll examine the so-called “Procedures, Alternatives, and Risks” (PAR) discussion prescribers are supposed to offer patients. You’ll see that a truly balanced presentation is close to impossible—but there are some potential solutions. Thanks for reading this far. I hope you’ll return for the next go-around.

Well good to see you are open to debate but my first sense in reading is that in some ways it’s a moot point . It is a lens and it does need to be discussed. However, it’s just biopsychiatry which is in my opinion much more of an issue.

The approach of a pill solution can even be found in Frank L Baum’s Oz series. A pill not does not and never will solve intergenerstional trauma, environmental hazards affecting one’s life, vocational isdues, economic issues, family issues, abuse and let’s be specific her emotional, verbal, physical, and sexual. It does not in any way solve being bullied. It does not solve luck if the draw isdues like your school class mates or neighbors. It does not look in any way into your family culture and heritage. Pills do not have ears. Pills not not have souls. Pills can help posdibly take the edge off or allow sleep but better living through chemistry no matter which chemistry one is referencing was and is most times a lie. Insulin is life saving. Antibiotics are life saving. But dealing with a human being crisis requires so little the ability to listen and or ask respectful questions. The sign of a great teacher of Amy trope or type is when they encounter a human being with new ideas and they react with awe and wonder well how did you come up with that idea? I had thst happen to me in academic settings never ever in the mental health field when Suppossedly being treated.

And the lack of historical content on alternative therapies is a concern. Long , long history depending on what country and cultural and time period. United States Military especially after the two world wars used extensive alternative therapies. Can you list them for us and discuss? That would also be an interesting dialogue! And also which ones you yourself used as a clinician?

I think the isdue you raised in how many folks have endured ill effects or the old sawhorse side effects is a good point. So hard to say. My mother quit her three pack a day cigarette habit after my siblings and I did a fillip force effort to get her to stop. She did it cold turkey and was miserable to be around for a year. She gained weight and just said she would still have very pleasant dreams about smoking. And yes she died of lung cancer after thirty to fifty years of not smoking. She was addicted and in withdrawal but none of us knew that at all. So if an educated woman could figure out her withdrawl symptoms or discuss them and my guess is she somehow figured it out because she knew and worked with folks who were to alcohol but there was never a key or sn open door or a path to follow to begin acknowledging the problem. And my best guess is more like her than not and with other chemicals whatever one one wants to call than not.

It would almost take sn all out public health campaign like tobacco to slow for your research wuestions. Back in the day the advertising folks showed white makes in white lab coats saying my cigarette of choice is this one. And if my family never talked about how she was in withdrawal with the massive public health campaign then again my best guess there would still be folks with problems using whatever one wants to call them but not able to talk about. And if I remember correctly the campaign against smoking was for cancer and death and not a word about addiction.

Yul a runner taping his promo knowing it would be played after he died and no acknowledgement thst he was addicted to the substance or again whatever you want to call it.

So tslk but expand your lens s small lens never fully sees the entire human being.

Report comment

to MIA: I would like to be able to reply to Jim Phelps, but I can only reply to someone who has previously commented?? Why is that? If it is became is was written a week ago, then why did it only show up in my inbox today? If you could kindly explain how to reply to the writer rather than a commenter? Secondly, it would be awesome if there was a “like” button next to comments as there were so many excellent ones, but no method to say so.

Report comment

I think you can just comment on the article and if the author is reading comments, they will consider your comment as intended for the author.

Report comment

And as always I deeply apologize for my dyslexia and dysgraphia! I need an editor!

Report comment

I’d be willing to take that job, Mary, since I was able to decipher common sense in what you said … based upon my lived experience … in the same (IMHO, and based upon a lot of psychopharmacological research) psychiatric iatrogenic illness creation system.

Jim,

I appreciate your trying to take a middle ground. As I do see the two extremes do need to come together, in order to eventually bring about a peaceful solution. And the same is true for too many, not just psychiatry, of Western civilization’s bad systems now.

I also appreciate that you’ve acknowledged some of the many psychiatric and psychologic industry’s systemic problems.

I could pick a few morsels out of this blog, and critique you now, but I have oral surgery at 7:30 tomorrow morning, so need to go to bed. And maybe it’d be wiser for me to critique you, after you’ve finished your third of three blogs anyway?

As you appropriately noted, there is a huge problem with too many within the psy professions not actually bothering to listen to their patients actual concerns, not actually being knowledgeable about the common adverse and withdrawal effects of the antidepressants, resulting in lots of misdiagnoses and malpractice.

And, of course, such systemic psychiatric and psychological malpractice – without proper compensation, while most doctors have malpractice insurance – and after the doctors had promised to “first and foremost, do no harm.” Well, such medical betrayal is … I agree … worthy of a much needed apology.

Report comment

Thanks Someonelse for your kind offer. I was helped by a parent when I put out a newsletter for families with IEPs and 508s in our community. And also by secretaries and my aunts who were secretaries. I am sure someone at MIA can forward you my email if your kind offer is still on the table. Thanks.

Report comment

Posting as moderator:

If you want to connect via email, please let me know.

Report comment

I am really baffled by the coms posting order, ot lack of at all, and the filtered against continuously spelled letters, carefully chosen from the standard alphabet to convey an accurate meaning to try to be clear and not otherwise, you know…

It’s like I’m morphing into a R, hob ot(sic) to evade another… Even typing into the square room might be deserving more Shcrut in E.

But if the self instantiated in the keyboard actuator does not do the square thing pushy thingy, the too self aware selfie can’t edit… squares and letters… and typical Os, to be shortened like a good brEad, with capital emphasis to close the gap in the missing ends…

🙂

Or, I know so many metaphors, am I overengaging with my imagination drive?.

J, looking over the part that connects me upper extremity to me central hub of the instantiated self imagines looking thus superfluous. And wrongly.

🙂

The movie: “How am I driving?” rights W apt…

The typist not clearly stated does fear and wonder, literally: wearing in front a blank page is to be following, and ED, instead of hid in the, OJ, backed 3 letters, distant future?

To make another instantiation: my short fictitious story* is actually more Of, and then another same push in the black thingy in front of me, than accurate descriptions!.

And yet, it came with flying colours in record time, and the technicals are yet to be read beme in the coms…

As they said in “The Big Bang Theory”: “I smell R…t”.

*About the radar posts. And to be clear neither are, as far ICS, off ing. They were not intended thus.

Report comment

I don’t want to write like an ordered compact array of otherwise fluidity that descends from the altitudes, diverse looking as they may seem, ironically. I just got that!.

I admit there is a point in the adding pluses and minuses, but the blank page to say something in the international, islandic experience is not an alternative to not conforming.

And I refuse! specially because the let loose was probably trained in the flame wars now tried to address partially in top blacky robby quarters.

So, double refuse, it’s not apt. But I can imagine why: it starts with an L and ends with a why?. And incentives, I guess…

Report comment

Double agreement on the top scores seems suspected, Doesn’t it?.

And appealing to R authority can be used in excercise of judgment. Egowise.

But, now, I am really going into netless ground.

Report comment

These drugs have been on the market for 40 years, ruining and ending countless lives. The fact that the people who created this holocaust are still denying it and lying every step of the way (“we never said there was a chemical imbalance theory!”) is proof enough that they’re irredeemable con artists who will always only re-victimize the patients they hurt at every turn.

Report comment

One thing standing out for me is that it equivocates SSRIs with antidepressants.

Cocaine and other estimulants, like amphetamines were used as antidepressants. Then, just like SSRIs were claimed to be successfull, and had side effects, not recognized at the “beginning”.

Then there were tricyclics and other atypicals before fluoxetine.

And the added story of ALL known chemical/synthetic antidepressants paint a picture of close homology, almost identity between claims of successful treatment, failures and severe side effects.

I bet that with cocaine and amphetamines there were attempts to help withdraw people of those when used for depression as there are now, apparently, for SSRIs and SNRIs. Just these ones are more difficult to withdraw from.

So I think JP is omiting that for brevity, but it is an important omission to address, I think.

Report comment

You can’t expect anything but deny, deny, deny.

Report comment

I’m left, after reading, feeling that something is missing in this article, perhaps many somethings. The first thing that jumps out is the lack of discussion of the power dynamics at play across the wide spectrum of how psychiatry actually intersects with society. You said that the larger psychiatric establishment has more avenues to advocate for itself than patients-yes. Not only does it have more avenues of advocacy it also acts in a legal fashion, it shapes policy related to our Justice system, it does in fact weaponize itself against the very people it is supposed to help as well. The political and economic aspects of psychiatry’s entanglement with law endorment and greater city policies cannot be ignored because it plays such a significant role in how psychiatry is perceived and in fact practiced. So the power dynamics at play create a very uneven playing field where perhaps a “middle view” is actually not warranted when people have been subjected to societal abuse for so long. This is a reality that psychiatry has to contend with. Additionally, yes there has not been as much research done on withdrawal specifically, but there has been much research done on outcomes. Time and again the science doesn’t match the practice when it comes to the validity of the psychiatric status quo. The science underpinning the field is incredibly weak and yet is propagated as gospel almost to a dogmatic degree. People who have experienced withdrawal, and frankly any person who has experienced the practical corruption of medicine and healthcare in the US, understand there is not a fair playing field and perhaps may never be precisely because of the political and economic factors involved. Subsequently, psychiatry is not interested in community based or person-centered solutions because they would fundamentally require two things our system is not interested in giving: time and money. There are so many alternatives out there to psychiatric medication, so many. Access to them has been purposefully limited by compounding socio-economic and political factors. Also, if psychiatry truly wanted to progress and help people while keeping their biomedical model, it would become an interdisciplinary specialty that combines neuroscience, immunology, endocrinology, and gastroenterology (minimum) because these are all the physiological factors at play in “mental” health. But not only do we not have a health system at large that in interdisciplinary, we also know that our psychological and emotional experiences are heavily influenced by life experience and environment. We have SO much research demonstrating how our environment and the things we experience in life shapes us. Psychiatry actively ignores a wealth of explanations for human behavior in their search for the magic bullet that will finally legitimize their profession. The answers are already out there. But to see them would be to admit that they got it wrong. I really do not know what it will take to change this establishment and/or make them even want to change. I know that individual practitioners make up a field, and that many may be frustrated or dissatisfied or feel like they don’t have the right tools. But the path of least resistance in strong. It clearly is stopping a number of practitioners from changing, across both psychiatry and psychology. I applaud the effort to see both sides because understanding all sides in necessary to make change. But there is so much more that needs to be addressed within this field that directly relates to why we have the current withdrawal situation we do. And one last point, when service users are talking about severe or extremely severe withdrawal we are talking about disability that for some may be life long-iatrogenic harm that has no path of recourse to Justice. This is disability that profoundly effects people’s ability to work, to live, to have relationships. This type of harm has been going on for a long time. Psychiatry will need to actively work with these people, to seek their counsel, to openly give them a seat at the table of trust is ever to be rebuilt. There is real betrayal by medicine here that is actively affecting thousands of peoples lives while companies make money off their suffering. Of course it’s hard to see a middle ground. There is no middle ground until psychiatry can come to that table of recompense. And frankly, it never seems like they want to. I really do feel these types of conversations and debates are good and necessary. However it does also give me “tactics of the oppressor” vibes-“just try to see our side!” What is the validity of a side that trades in ethical and financial corruption, forced treatment, scientific misconduct, dogmatic defenses, and gaslighting? I think a serious point being missed from the survivor community is that psychiatry as it stands should not exist. There are plenty of far more loving, empathic, community-oriented models to take its place. When the system is the problem, there is no middle ground-there’s just a different system.

Report comment

It might be that the middle way proposed is more like a third way, not in the middle, just a different offer, apparently.

And as such, open to analysis. And JP I think has admitted that omits info from prospective withdrawers of SSRIs and SNRIs, like akathasia. If I am not misremembering nor misunderstanding because it can be SO severe and unpredictable.

So, in the regard of complete information for consent, JP is more into the mainstream: deciding for patients instead of letting them do that.

Some parts of this post by JP do speak to me of some difficulty appreciating that consent, informed consent does go hand in hand, is integral to the fact that people can go in deciding from 0 to 100%. Like “Rashes”.

For patients it’s about patients’ values, not practitioners’ values. That is consent and medical ethics 101.

So, JP aligns more with the mainstream there too: apparently can’t appreciate enough people decide for themselves in ways that are congrous with patient’s values.

And that can appear surprising for some practitioners, not for patients, because practitioners think too much of their own values, at least. Oddly, after some times admiting ocasionaly their ignorance of something that would pass as basic for patients.

Report comment

That’s such beatifull insightfull correct and succint view of the issues.

I do share a lot of the feelings and ideas expressed in your comment.

I just want to add that for individual practitioners choosing to keep doing, every day, of every week, of every year the same, for decades, does not speak of trying to change or do goody goody.*

Particularly when no honest, fully transparent and complete explanations of harms, intentions, motives, incentives has come, or will come from said practitioners, even researchers.

And more recalcitrant when no apology emerging from such prerequisites emerged, or is to emerge from continuing practioners, and researchers.

It sounds to me window dressing, false alternatives, more of the same in an “alternative” or “progressive” looking way. And looking the other way too!.

Great post of yours, maybe just splitting the paragraphs might improve the already heightened estetics.

😛

*Note: In medicine claiming one practitioners practice is now according to new published research can’t be considered neither progressive nor progress. It has always been like that:

Pracitce of medicine is one of the few, maybe only economic activity where knowing more does not increase one’s income. Any investment in continuing medical education returns exactly zero more income when compared to the income, let alone profit, before “updating”. Ex learning to do something not previously done by the practitioner: like now treating something I did not treated before.(Psychiatry I am looking at your ever expanded and more vague diagnoses).

So the lone claim of I read the new articles and I changed my practice accordingly is not progress nor improvement, it is the way it always was.

And that is anti-investment in knowledge, in the sense such investment is bound to return more profit allocated somewhere else.

Investing in more knowledge in other economic activities does lead to, or should lead to more income, not just staying in bussiness.

Psychiatry and medicine are after all a monopoly of the restaurant kind: each restaurant owns by itself the brand, but there is competition from other restaurants. They are monopolistic competitors in that sense, and there is barrier to entry into medicine and psychiatry’s practice.

And medicine aspirants are not effectively aware of that either: disinvestment. As they are unaware of the bollocks of psychiatry. And of monopolistic competition.

And it’s also a disinvestment in the long term kind of way: they are decreasing the customer pool and decreasing the payers pool by increasing disability and for those no disabled forcing them into dependency or very low paying jobs.

Despite the obvious facts that many commenters at MIA who are survivors deserve way higher paying jobs that practitioner posters at MIA. As far as I can infer…

So to me there’s also wealth transfer of the Hood Robbing kind: from the deserving to the undeserving. Some have to be at least dishonest to have an income, not otherwise available to them…

Report comment

“Their protests to the contrary have even been seen as indications of a personality disorder. Really?”

The death-knell diagnosis of borderline personality has been used widely, for decades, by psychiatrists to bolster themselves against valid claims of malpractice. Anyone who is surprised that “personality disorder” diagnoses are used in this way is naive to the depths of depravity exhibited by psychiatrists.

Report comment

If BPD is so common, and it technically is in patients who seek or are forced into treatment if psychiatrists actually bother to read the Statistical part of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM), you would think that it would be more common practice to screen for so called personality disorders like BPD before prescribing.

Diagnosis by poor response and frustration with treatment is a bad way to both diagnose and treat. It belies supposed usefulness of a full diagnostic exam if you can’t detect “personality” until a suffering person is feeling worse due to treatment.

Report comment

If you look at it from the perspective that they hate us, want us dead or disabled and want to make sure no one ever believes our malpractice claims, it makes sense. If you look at it from a perspective of them trying to help us or at least to do no harm, it makes no sense.

Fortunately, they have provided plenty of evidence that they hate us.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9567085/ “Results suggested BPD patients are viewed by mental health professionals as ineffective, incomprehensible, dangerous, unworthy, immoral, undesirable to be with, and dissimilar to the mental health professionals. Moreover, disgust propensity and the pathogen component of disgust sensitivity were associated with stronger negative attitudes towards BPD patients.”

Report comment

This is a very balanced article. Mr. Phelps is mainly focused on antidepressant withdrawal, not on antidepressant efficacy or the sins of psychiatrists. As is the case for much of medicine, there may be no final answers, but he has a very reasonable approach concerning this one issue.

Report comment

The 2005 article by Sir is after 8 weeks of antidepressant use.

We know that the longer you take an antidepressant the more likely you are to have withdrawal effect and the more likely they are to be severe:https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40263-022-00960-y

It is pretty incredible that after just a few weeks of exposure to venlafaxine 1 in 20 people have at least severe withdrawal effects and that 1 in 60 have very severe withdrawal effects.

After years on these drugs we would expect this to be a lot more people.

Report comment

After years on any drug, the person (and those around him) has forgotten what it feels like to be undrugged. Withdrawal effects such as anhedonia, emotional blunting can easily be interpreted as “that’s just me.”

I actually think these effects are far more scary and devastating than physical pain etc.

I married someone who had been on psych drugs (not anti-Ds) for around 6 years already, and it took me around 10 years to get him off them, with tons of withdrawal effects. But it’s still in many ways like being married to a shell of a person. How much of that is due to the drugs’ effects, and how much is due to the lived experience of “being a person who needs to take psych drugs” is a good question. Plus more.

But because people are all different (something psychiatrists would do well to accept), withdrawal effects of course are widely divergent.

Report comment

Another issue to me not clearly stated, but that stands out to me is that the diversity in reported rates of symptoms of withdrawal: all, severe, life threating, speaks to me not ONLY of differences of definition, but of IGNORANCE:

If there were 30 to 50 meds, SSRIs SNRIs and each had 20 to 30 scientifically, mechanistic, beyond doubt symptoms of withdrawal, and only 4 to 5 were present in a given patient, then the clinical picture in the aggregate of patients will be close to the life diversity in the Amazon. But not as easy to pick apart just by “looking” at them…

And the scientific, mechanistic, beyond explanation of it’s benefit is not only lacking, is plagued by false claims. The withdrawal part, by incentives, is bound to be as “data” even more suspect, if that were possible.

So, based on that: how is this reader expected to swallow the explanation of inconsistent definitions as an explanation?, when in fact it’s the ignorance of the biological, fundamental mechanisms and it’s correlation with “symptom expression” that, as empiricism based on false logic, stands in the way of doing research to tackle that.

First stand, then baby steps, then walk, then if safe run… from psychiatry.

I am not advising though, running from psychiatry does come with its owm issues.

And I am not unaware of how that speaks of a bigger ignorace of biology by biological psychiatry…

That won’t be addressed with apologies, but with corrections of the published medical record. As now, still strong, Robert Whitaker is trying to pry from the “establishment.

https://www.madinamerica.com/2023/10/the-american-journal-of-psychiatrys-answer-to-mia-a-silence-that-speaks-volumes/

Report comment

About the QUESTION what to tell, to effectively warn a patient what to expect when withdrawing my answer is:

How would ANYONE know now what each unique individual is to expect when withdrawing, IF the imputed neurochemically mechanistic, obfuscated by false claims and full of ABSENCE of detailed causal explanations renders any PREDICTION efforts a CHARADE?.

It’s exponentially worse than predicting 9 of the past 5 economic recessions!. I do love and respect economics though.

That sounds to me like asking another form of: “What are we supposed to do?”. See: you are the expert, that’s what YOU are supposed to justify with science, care and humanity, not me, YOU.

So to sum up, if there is no way to justify, to make true claims about future events by psychiatry for people trying to withdraw that question is a deceptive one.

Justification in the sense of to CHOOSE…

Because to me the legal, ethical, scientific obligation would be: admit ignorance and wrongdoing. And stop hooking people on these stuffs: chemical and pseudoscientific.

Even saying 1%, 2%, 10%, 30%, 50% is a distraction of the fact there is no way to calculate those numbers because they are empirical correlations without scientifically valid causal explanations AND those correlations are based on logical arguments extended into empirical theaters based on false premises.

False premises and bad logic are like the 8th passenger: they start in the textbooks and classrooms, cling to the research proposal, distorts and negate the published findings and sometimes “land” on the patients’ faces.

To then “emerge” during the withdrawal process…

And that does not start to address how those empirical correlations are landed, are relevant, are expressed in each unique individual trying to withdraw.

So, to me, no prediction possible, no way to choose. Fortune cookies with oblique statements that may or may not land on this unique individual?.

To paraphrase MK, the physicist: Psychics of the Impossible!.

If I put MK’s name, apparently, I can get boted and booted…

Report comment

Agree completely here. They should dispense with trying to nail down percentages and predicting how any given person will react.

OTOH, yet another aspect of informed consent would be: “if you do experience side effects/adverse events/worsening physical health/withdrawal syndrome… basically any negative outcome from the prescribed drug…there is a strong possibility that you will not be supported by the health care system. There’s every likelihood that doctors will write things in your medical records like “personality disorder “, “non compliant “, “hysterical/hypochondriacal/delusional”, that will effect the quality of care you receive going forward.”

People need to be told that some wind up disabled from psych drugs. And for those that wind up disabled, the “official cause” of the disability will be “mental illness” not “disabled due to iatrogenic harm.”. For the rest of their life, the person will be seen as untreatably mentally ill rather than someone who was severely harmed following doctors’ advice/orders.

Report comment

The second paragraph is like the unbreakable contract of the movie “Intolerable Cruelty”.

So beautifully written by you.

You are not giving me the green eyed look, right?.

Just kidding, that looks was powerfull, as your second paragraph.

And so are you.

Report comment

Thank you :). I have not seen the movie.

Report comment

Finally, the last alternatives part of the “essay” looks tendencious to me:

If there is no available alternative to treat the patient, sometimes the best, sometimes only course of action is to first do no harm, and explain the patient why he or she is not a candidate to exchange, to switch the treatment INDICATED to him or her.

This burdened reader is not suposed to remind a colleague in activity that’s how medicine IS, in fact, supposed to work: If me, the practitioner can’t provide the treatment the patient requires, that is indicated individually, specifically, me, the practitioner IS to abstain from providing nonsense for MY patient.

And to be clear about it, why, how, and what to do about it. At least, because that gives the patient the choice, the option, sometimes, if rare even, to buy another insurance, search and get another job, etc. Move to a country with social health care even.

Not doing so not only exposes patients to harm by treatments innapropiate for them, it closes their choices to do something NON-MEDICAL about it. A clear, direct, patent, harmfull, prejudicious extension of medicine into legal, market, etc., issues.

Where docs are worse than the average citizen at least because of hubris, and the opioidal fumes of “expertise” of the “we want to save lives” kind…

And not doing thus, does stress the fact that psychiatry is a market: yeah, we can fix that, we have tons of medicines for a lot of ailments. Like a traveling false remedies salesperson of yore…

“In psychiatry indication is not required, only a prescription is needed”. Symptomatologists, not real medicine people…

Report comment

Another issue to me not clearly stated, but that stands out to me is that the diversity in reported rates of symptoms of withdrawal: all, severe, life threating, speaks to me not ONLY of differences of definition, but of LACK OF KNOWLEDGE (not otherwise stated clearly):

If there were 30 to 50 meds, SSRIs SNRIs and each had 20 to 30 scientifically, mechanistic, beyond doubt symptoms of withdrawal, and only 4 to 5 were present in a given patient, then the clinical picture in the aggregate of patients will be close to the life diversity in the Amazon. But not as easy to pick apart just by “looking” at them…

And the scientific, mechanistic, beyond explanation of it’s benefit is not only lacking, is plagued by false claims. The withdrawal part, by incentives, is bound to be as “data” even more suspect, if that were possible.

So, based on that: how is this reader expected to swallow the explanation of inconsistent definitions as an explanation?, when in fact is the lack of knowledge (not otherwise stated clearly) of the biological, fundamental mechanisms and it’s correlation with “symptom expression” that, as empiricism based on false logic, stands in the way of doing research to tackle that.

First stand, then baby steps, then walk, then if safe run… from psychiatry.

I am not advising though, running from psychiatry does come with its owm issues.

And I am not unaware of how that speaks of a bigger lack of knowledge (not otherwise stated clearly) of biology by biological psychiatry…

Report comment

Oh, the doggy, Myne, intercalating and transposing!.

A bee oooh tee, I’m not a golf fan, but I met some dudes that were, is prioritizing MIA posts!.

Or there is misdirection I admit. My lack of knowledge was a stand inn for the unspelled starting in I, and ending in the last three of nuance.

With a geeh! at the second, and who’s on third? Nnnnoh, really can’t tell.

Orance can see?. Does it really see it?…

Same as the word demise, starting with a konundrum ending in ill, repaced by demise or fatality in:

https://www.madinamerica.com/2023/10/the-war-on-suicide-is-making-things-worse/#comments

That’s why the coms come discombobulated, as Yoda would say: hummm!. And some kept to the mono phrasing…

Yeah, I might not post the first premises and conclusions in:

https://www.madinamerica.com/2023/10/maid-and-mental-illness-an-interview-with-dr-jeffrey-kirby/

I refuse to be bound by a gpeteer lacking human understanting, mesmerizing, see? I can use metaphor, to explain logically what otherwise not even MIA contributors can.

Suit yourselves.

Words filtered, meaning unnapreciated, all soo gpetied. And so prone to “ego” abuse.

Now I see geepeetees posts under a more crappy light.

It turns out we squirmed not the beeh ooooh teeeH!.

Report comment

Didn’t you say they were symptomatologists? Because Jim visited the Surviving Antidepressants site, where the high histamine symptoms are dancing with the hyperhomocystenimia symptoms and at the end of the show they vow and scream, “We are caused by MTHFR C677T homozygous mutations and antidepressants”

I mean, they don’t actually dance or scream, it just seems like it.

Report comment

Please tell me why we need a so-called “middle view” on antidepressant withdrawal?

It is the responsibility of the author of this blog to indicate what particular books, or writers at MIA and other websites, have allegedly exaggerated antidepressant withdrawal effects, and THEN scientifically critique their so-called errors point by point.

Without such a scientific critique of other authors and their writings, this blog represents nothing more than a “straw man argument” that ends up covering for the crimes of Big Pharma and psychiatry.

Richard

Report comment

Richard,

I agree completely.

Report comment

I doubt that accurate data on the percentage of people who experience severe withdrawal from psych drugs, as well as the severity and duration of the withdrawal, will ever exist.

If most patients who had been diagnosed with a mental illness and prescribed psych drugs had a trusting relationship with their prescriber and with the health care system in general, it might be within the realm of possibility to obtain accurate data, but most patients know better than to tell health care providers everything they’re experiencing.

One has to ask, regarding the people who went off the drugs without speaking to their prescriber — why didn’t they? Why did they go it alone?

There are documented aspects of withdrawal (which we know at least some people experience) that involve suicidality, severe agitation, intense despair. Most people wouldn’t be vocal about these things because they know that the prescriber might then feel legally obligated to commit the person. Even putting aside the fear of commitment, most patients realize that if they complain too much or too loudly about withdrawal problems, they will likely be told that that’s their mental illness, the drug doesn’t do that, the drug is out of their system, etc. Patients know what happens if they’re “too honest”.

Report comment

Getting gaslighted as a “psychiatric patient” is par for the course.

Report comment

I like this article. Mr. Phelps is not discussing the efficacy of antidepressants but only asking how difficult it is to withdraw from the drugs. He gives a reasonable description of what withdrawal studies have found and admits to their limitations. He points out that no matter how the withdrawal risk is presented each individual will evaluate it differently based on what they see as their alternative.

I think that’s a balanced approach, even if you think antidepressants are totally worthless.

Report comment

thanks for your thoughtful essay. I’m particularly interested in your part three with a hypothesis around why only some people get withdrawal symptoms.

Report comment

Try reading these books before making claims about psychotherapies research

William M Epstein:

The Illusion of Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy as Religion

Psychotherapy and the social clinic in the united states, soothing fictions

Paul Maloney The Therapy industry.

Report comment

I think this author has a problem facing reality.

Report comment

Me too. It’s very upsetting that this is presented as a “middle view”. If informed consent is that much of a problem or quandary or sticky wicket for psychiatrists and other drug prescribers, that says that either: the drugs are dangerously unpredictable and cause reactions in people that we still don’t know or understand the scope of, in which case they should be taken off the market. Or, informed consent should just be taken off the table completely: The informed consent should be “we don’t/can’t provide informed consent” for our treatments.

Report comment

Yup. It’s too bad this guy doesn’t know the difference between “middle view ” and “muddled view”.

Report comment

…and why doesn’t he see anything wrong with prescribing drugs for non-illnesses???

Report comment

Yeah, exactly.

This is starting to feel like those political debates where the opposing sides argue interminably about data points while the people who are most impacted by the issues being debated eventually realize that nothing is going to change.

Report comment

The bean counting’s been going on for years and it’s never gonna change.

Report comment

Yes the drugs should be taken off the market, but it is complicated. We don’t want current users to have to abruptly stop because the drugs are off the market. A good start would be FDA mandated “black box” warnings.

We should be sure that actually effective depression treatments are available and affordable to all. In the section “The Context: Alternative Treatments” the author lists several alternative treatments and why each may not be available, starting a to do list for people working to improve depression treatment.

The author has promised in the 3rd essay to reveal a hypothesis for why some people have severe withdrawal symptoms, while others have little or none. I hope this can be tested in a rigorous study without pharma funding or influence. However, even if we can know with certainty that a patient will easily withdraw, that does not mean that drugs are the best treatment. They are among the cheapest alternatives. Also the least effective (citation needed).

Report comment

”I’d like to present a sort of middle ground, where the views of both sides are respected”

The question of the prevalence and severity of antidepressant withdrawal is a scientific one, not a political one. Should we try to respect both sides regarding climate change, too? Or the theory of evolution?

We don’t need a middle ground, and we don’t need to strive for agreement. We need more research, and the research has to take delayed withdrawal into account. Until then, doctors need to assume the worst and practice a harm-reduction approach.

The prevalence may very well be in the middle of psychiatry’s and the survivor movements’ estimates, but advocating a middle ground for the sake of it is a flimsy way of tackling a medical question.

Report comment

”I’d like to present a sort of middle ground, where the views of both sides are respected”

The question of the prevalence and severity of antidepressant withdrawal is a scientific one, not a political one. Should we try to respect both sides regarding climate change, too? Or the theory of evolution?

We don’t need a middle ground, and we don’t need to strive for agreement. We need more research, and the research has to take delayed withdrawal into account. Until then, doctors need to assume the worst and practice a harm-reduction approach.

The prevalence may very well be in the middle of psychiatry’s and the survivor movements’ estimates, but advocating a middle ground for the sake of it is a flimsy way of tackling a medical question.

Aurorax

Report comment

Science is not created by consensus, and does not have any consideration for a “middle ground.” Are we going to start saying that gravity is inconvenient for some people, so we’re entertaining some small modifications to help people adapt?????

Report comment

[Moderator: I posted this several days back but it looked like the system didn’t save it? This happened twice. Please post and delete this note. Thank you.]

Thanks for this point of view, Dr. Phelps.

As we all know, going back 35 years, the problem of withdrawal from the newer antidepressants and other psychiatric drugs has been all but ignored by academic psychiatry, for reasons we can only guess. Someone studying the sociology of medicine should investigate this.

Psychiatry’s obliviousness to withdrawal has been so pervasive that in 2021, a Cochrane review team led by a GP, Ellen van Leeuwen, exhaustively reviewed decades of antidepressant trials with discontinuation designs to see how their tapering schedules affected the rate of withdrawal symptoms.

Of the 33 studies meeting criteria, all conducted by the cream of academic psychiatry (many paid by pharma), only one contained protocols to distinguish withdrawal symptoms from “relapse”, which the discontinuation studies found in abundance. Psychiatry’s elite took this to mean that their goal to show the efficacy of antidepressants was confirmed.

However, the Cochrane reviewers concluded that even with this vast volume of academic activity, due to the confounding of withdrawal symptoms with “relapse”, there was a dramatic vacuum of knowledge about efficacy as well as withdrawal and what might be more effective tapering of antidepressants. In short, medicine knows nothing about this.

It’s taken mass outcry from patients, many who have learned from social media that the bizarre and sometimes incapacitating symptoms they felt after they went off their antidepressants were, in fact, withdrawal syndrome, and that’s what’s put this dilemma in front of clinicians. (By the way, there are several reasons why patients might not have gone back to their doctors with complaints about withdrawal, as suggested in Phelps et al., 2023, a principal one being they might not have known that their strange symptoms were withdrawal.)

Given the laws of pharmacology, it is unaccountable why antidepressants have long enjoyed the undeserved status of psychotropics that somehow evade the natural neurobiological processes of adaptation, dependence, and thus withdrawal risk so obvious from psychotropic drugs somewhat arbitrarily classed as “addictive”.

Why would antidepressant withdrawal be less likely than from that of, let’s say, daily chlordiazepoxide (Librium), a benzodiazepine that shares a similar half-life of about 24 hours with many antidepressants? There was a huge scandal over Librium withdrawal in the ’60s, when it was liberally prescribed to anxious housewives. Benzodiazepines were internationally restricted as Schedule IV drugs in 1971.

When it comes to risk of withdrawal, why is there a halo around antidepressants but not benzodiazepines? (I contend that among medical professionals, there’s a quasi-religious belief in antidepressants that’s impervious to evidence, but that’s another topic for medical sociologists.)

So what should clinicians tell patients about risk of withdrawal? My conclusion would be that whether the frequency of withdrawal syndrome is 20% or 80%, the takeaway for clinicians should be that withdrawal syndrome occurs “often” — not “rarely”. And upon prescribing, clinicians should visualize a taper plan for that patient, because anyone can experience severe withdrawal effects, which will be the prescriber’s responsibility.

I do agree with you that the general public shares with clinicians that quasi-religious belief that antidepressants are miracle drugs, and that warning about withdrawal risk will not keep people from asking for them. But doctors should not be reassuring themselves that the odds are in the favor of an antidepressant miracle. Clinicians should portray the risk realistically because it’s the right thing to do.

(By the way, Medicating Normal was an independent film production unrelated to SurvivingAntidepressants.org or any of the peer support groups that has developed a well-deserved following among the patient movement. It’s is a devastating, insightful film about the drug-riddled way we live now. Everyone should take the opportunity to see it.)

Report comment