Neil Gong is an assistant professor of sociology at UC San Diego, where he researches psychiatric services, homelessness, and how communities seek to maintain social order.

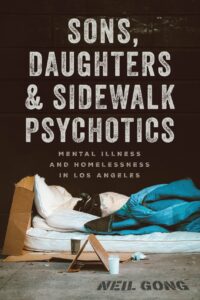

Neil’s new book, “Sons, Daughters, and Sidewalk Psychotics: Mental Illness and Homelessness in Los Angeles,” published by the University of Chicago Press, offers a detailed look into the starkly different worlds of mental health care in Los Angeles. He contrasts the public safety-net clinics, which strive to keep patients housed and out of jail, with the elite private care centers that cater to the wealthy. He finds that while the public system focuses on survival and containment, often providing only minimal care, the private system aims at rehabilitation and respectability, albeit sometimes at the cost of personal freedom.

Neil’s extensive fieldwork included spending nights in homeless encampments, shadowing social workers, and engaging with patients and families across the socioeconomic spectrum. His work highlights systemic failures and societal indifference but also the humanity of those working and living within these disparate treatment systems.

In our conversation, we unpack the critical insights from his book and explore the broader implications of his research. How do these disparate systems reflect our societal values? What can we learn about the intersection of mental health, homelessness, and social policy? And perhaps most importantly, how can we move towards a more equitable and humane approach to mental health care?

The transcript below has been edited for length and clarity. Listen to the audio of the interview here.

Justin Karter: To get started, could you share a bit about your story, who you are, and how you became interested in mental health, homelessness, and disparities in psychiatric care?

Neil Gong: For a long time, I thought I would become a mental health practitioner or perhaps a clinical psychologist, partly because of things I’d seen family members and friends go through. My first job after college was on a community mental health treatment team, where we worked with people diagnosed with serious mental illness who had been long-term street homeless. I observed many systemic issues that many of us are probably familiar with: people cycling in and out of jail, returning to the streets, and experiencing brief hospitalizations that didn’t seem to offer much help. In some cases, these interventions were chaotic and sometimes against people’s will. I was trying to make sense of what was going on.

At the same time, I was involved with some service user activist groups, which gave me a real sense of how broken these systems were from people’s lived experiences. Eventually, I shifted my focus, deciding that I didn’t want to be a clinical psychologist after all. Instead, I wanted to focus on systems, so I pursued a PhD in sociology. I ended up at UCLA, where I did some fieldwork and became very interested in ethnography as a research method. I wanted to map out the organizational and economic components of these systems, seeing them on the ground to understand how referrals work, what classifications are needed to access certain services, and how these services interact with the police.

Ethnography allowed me to do both of these things: map out how different organizations work together—or don’t, given how dysfunctional things often are—and spend time with people to get their personal takes on their experiences. I wanted to capture the existential and human dimensions alongside the structural, systemic machinations.

So I ended up in Los Angeles, and I found myself observing how LA serves as an interesting kind of laboratory of inequality in mental health care. On one hand, there’s the infamous Skid Row in downtown, known as one of America’s homeless capitals. On the other hand, you have West LA and Malibu, where wealthy people go for addiction and mental health services. Within one urban area, there are these two totally different social worlds. That’s how my book project, which started as a dissertation, came together.

Justin Karter: Your book moves between a zoomed-out sociological view of the institutions you interact with and the human stories and existential conundrums of the people you meet. Like many others about these issues, your story begins with deinstitutionalization. Can you set the historical backdrop for us? What led to the closing of the asylums, and how did that shape the systems you’re interacting with today?

Neil Gong: Much of what we see today in Los Angeles, as in other parts of the United States, can only be understood historically. The LA County Department of Mental Health, which I was studying as part of the public safety net, was born out of the deinstitutionalization movement and the idea of creating a robust community care system to replace the old asylums. There was great optimism about closing down asylums, which in the 1950s housed more than half a million people in the United States.

The history of deinstitutionalization is complex. Broadly, it was driven by well-documented abuse and neglect in asylums, spiraling hospital costs, and an overly optimistic faith in new medications. This created a perfect storm where progressives and leftists, who cared about patients’ civil liberties, joined forces with fiscal conservatives on the right who wanted to cut costs.

The history of deinstitutionalization is complex. Broadly, it was driven by well-documented abuse and neglect in asylums, spiraling hospital costs, and an overly optimistic faith in new medications. This created a perfect storm where progressives and leftists, who cared about patients’ civil liberties, joined forces with fiscal conservatives on the right who wanted to cut costs.

This moment of optimism was supposed to lead to the creation of a community care system to replace abusive and neglectful asylums. For the most part, that vision was a mirage; it never fully materialized. In my book, I try to weave between national, state, and local history to tell the story of deinstitutionalization from LA County’s perspective. The LA County Department of Mental Health itself was born out of this historical moment.

I read a story from Harry Brickman, a founding leader in the Department of Mental Health in LA during the 1960s. He recounted a meeting with then-Governor Ronald Reagan, where they agreed that Brickman and others at the Department of Mental Health and in other counties would have time to build up their systems before hospital closures and avoid too many discharges at once. However, Brickman claimed that Reagan reneged on this promise, leading to rapid hospital closures. Consequently, the new services, which were intended to be preventative, were overwhelmed from the start, dealing with people who were released and became de facto homeless without proper resources.

At the same time, it’s a bit unfair to place all the blame on Ronald Reagan because the truth is that many of these mistakes were bipartisan, with Democrats also supporting them. This situation unfolded alongside several other significant historical events from the 1970s onwards. In LA, one crucial context was the emergence of what’s called the “new homelessness” in the late 70s and 80s. People were released from asylums without adequate housing and support systems. By the 1980s, we saw the destruction of low-income housing and single-room occupancy hotels. In California, nimbyism (Not In My Backyard) further constrained housing development, driving prices up and pricing many people out, leading to mass homelessness across the state.

We often mistakenly conflate psychiatric disability with homelessness. The vast majority of people on the streets are not experiencing serious psychiatric disabilities, though they often face psychiatric distress. Understanding public mental health care involves recognizing that the challenges go beyond psychiatric disability and psychological distress to include urban poverty and homelessness. This also coincided with the rise of mass incarceration and criminalization, creating a perfect storm of issues.

Initially, this was the story I focused on. But as I conducted fieldwork, I encountered people in a different treatment world. I learned there was another way to tell this history: from the perspective of more privileged individuals who faced similar issues but didn’t have to worry as much about homelessness. Wealthier families could potentially divert a loved one if they got arrested, benefiting from a different infrastructure that emerged post-deinstitutionalization. This included private case management teams, private residential programs, and an infrastructure around addiction treatment in West LA. Today, we see these two different histories of deinstitutionalization playing out within the same city.

Justin Karter: I want to get into the tale of two mental health worlds here, but before we do, just a note on language. I noticed in the book you use the term “psychiatric disabilities,” and in other writings, you’ve used “madness.” Could you share a little bit about how you made that decision and the politics around the language?

Neil Gong: Gosh, I move between language depending on the setting I’m in, sometimes just so that people understand what I’m talking about. But yes, it is loaded and complicated. When people use the standard term “serious mental illness,” it often assumes a pathological model, typically a bio-psychiatric one. In reality, much of what we call psychosis is fundamentally mysterious. We don’t actually know what it means to explain it scientifically. We are partially informed by people’s lived experiences and what they can describe, but we need to remain humble about this.

My best solution has been not to insist there is one right way to think about it. Some people, including service users, believe that “mental illness” is the best way to describe what they’re experiencing. Others prefer a completely non-pathological way of talking about things, which might not even include the term “disability” and might just be “psychic difference.” I’ve used different language at different times to honor these perspectives. I try to rotate between terms, including those related to Mad Pride, while also using more clinical language when appropriate. In the book, I sometimes shifted language based on the historical context.

Justin Karter: Turning now to this major insight from your fieldwork, you describe two different mental health systems that aren’t exactly what one might expect. In the public mental health system, there’s more freedom, but what you call “tolerant containment.” Conversely, in the system for wealthy families, there is more “care and treatment,” but also much more surveillance and control. You do a great job in the book of sharing stories that illustrate these different care settings. Could you share a couple of examples that really capture this difference, where people with similar symptoms experience very different models of care?

Neil Gong: Sure. In the public sector, I observed what is considered a kind of gold standard model, the “housing first” approach. This model helps people get into independent housing without demanding sobriety or psychiatric compliance before providing access to housing. Community case management is attached to this, but the care provision is often underfunded or understaffed. Despite the best efforts of care providers, this often results in what I call “tolerant containment.” The focus is on keeping people off the street, out of jail, and preventing too many 911 calls. Essentially, they get people into a place and let them be, which can sometimes be empowering and respectful of individual differences but can also slide into neglect.

One example that stuck with me involved a woman I call Sandy, a white woman in her 40s who was moved from Skid Row into an apartment. She was considered a success in one sense because she was living independently. However, she repeatedly banged her head on the wall she shared with her neighbor, who was paying the market rate and was understandably upset. The Department of Mental Health’s solution was for Sandy to bang her head on the exterior wall instead to make less noise and reduce eviction risk. In some sense, this intervention was creative and respected Sandy’s apparent desires. But in reality, it highlighted the lack of resources for a robust care program, focusing more on preventing eviction than on providing therapeutic support. This approach, while arguably respectful, often seemed like a form of abandonment.

On the other hand, the elite sector offers much more care. Let me tell you about a man in his 30s, diagnosed with schizophrenia, whom I call Justin. He was receiving private case management services and living in a dual-diagnosis sober living home by the beach, addressing both mental illness and chemical addiction. He had just completed months of dual diagnosis residential treatment in another beach city in Southern California. His family was spending a significant amount of money on his care. Despite his privileges, Justin felt trapped.

I saw him in the Intensive Outpatient Program (IOP). He wished he could do more, but the medications made him very tired. He was expected to attend various forms of therapy, go to AA meetings, and do volunteer work, with little independence. He had reached the point where he was promised more privileges, but the program decided not to grant them. When I spoke to the staff, they said, “We think that without constant monitoring, he could end up like a psychotic street person, so we’re not giving him these privileges.”

That night, Justin ran away, got high on the beach, was picked up by the police, went to the hospital, and eventually returned to the high-end sober living home. Later, while doing volunteer work together, he said, “Neil, you kind of can’t get out of this place.” It was interesting because the program was technically voluntary; he wasn’t under conservatorship, guardianship, or any court order. Yet, he felt trapped.

What I want to highlight is that it’s not just about whether someone has a court order over them but about how much surveillance and control they experience from moment to moment. In the public safety net world, for instance, I visited board and care homes, which are psychiatric group homes. They had many rules but often no surveillance to enforce them. I was at one late at night, and people were openly getting high in the common area. When I talked to the owner, he said, “What do you want us to do? We don’t have the staff to smell people’s breath for alcohol or monitor them.” This kind of tolerance can become neglectful, contradicting the facility’s claims of surveillance due to limited staff and capacity.

Ironically, people in elite settings often felt much more controlled. Many of these programs don’t even take insurance, so well-off families pay cash, making them the true clients. As a result, their perspectives often take precedence over those of the person receiving care.

Justin Karter: It seems like a powerful metaphor that you have the freedom to suffer or even potentially harm yourself as long as you do it in a way that doesn’t disturb your neighbors or draw attention.

Neil Gong: Yeah.

Justin Karter: Hence the name of your book. For the wealthy, people experiencing psychiatric disabilities or extreme states are seen as “sons and daughters,” which comes with a sort of paternalistic care model that the title evokes. In contrast, the poor person on the street, the “sidewalk psychotic,” is treated as an embodied social issue. Could you say more about this discrepancy and the way we view these people as either potential family members or as symbols of societal failure?

Neil Gong: Absolutely. Ideally, we would treat people as individuals on their own terms. However, what I observed in these systems is that people are framed through other lenses. For families paying for elite care, the person is seen as a beloved son or daughter with an expected upper-middle-class future. The focus becomes how to normalize them and get them back on track with that vision. This comes with the privileges of resources, love, and a vision of a robust future, but also with the paternalism that can accompany it. Family dynamics are extremely loaded, and being controlled by one’s parents can lead to very difficult and explosive situations.

On the other hand, we have people who are deemed what I call “embodied social problems.” They carry decades of policy failure in their bodies and come to represent these issues. It’s easy to stereotype them as problems to be solved. This is often how treatment providers, even well-intentioned ones, view them.

I saw this with providers who genuinely cared and had progressive commitments to serving the poor and marginalized. Yet, they often thought of their clients in an abstract way, addressing them as issues to be managed rather than as individuals. While helping people find places to stay is crucially important, it reflects a different mindset compared to the therapeutic approach in higher-end settings, where social issues are not as predominant.

The title of my book aims to capture these two perspectives. By the end, I hope readers question how we can see people not just as sons and daughters in elite settings or as policy problems, but as individuals.

Justin Karter: What might that look like? What are the other lenses that could help us see people with these experiences in ways that are less paternalistic and make us less likely to avoid confronting the callousness and dysfunction of our society when we walk down the street?

Neil Gong: Yeah, I mean, this is tough. It’s a challenging issue. One big component, that people are working on now, is incorporating more peer perspectives into research, policy, and clinical care. This means truly listening to people who have lived through these systems, whether it’s homelessness, addiction, or serious mental illness, and integrating their insights to improve services.

Another aspect, that I hope to address with this book, is helping people recognize the frames they use. When we look at someone close to us, we might adopt a paternalistic family mindset and neglect the individual’s preferences or a civil libertarian model. Conversely, we might view someone we don’t know as a problem to be managed, ironically respecting their rights as long as they stay out of the way.

What we need to do is hold all these different perspectives simultaneously, be critical of them, and see through them. There’s value in not stigmatizing people but also in understanding their experiences from multiple lenses: as someone like ourselves, as someone we care about, and as a stranger. Ultimately, we’re dealing with one person, and we should consider what we would want for them from all these different viewpoints.

Justin Karter: I’m thinking about how this issue extends to the social and historical levels you write about in the book, what you call the “Frankenstein’s monster of civil liberties and austerity.” There’s a strange confluence where people on the left advocate for mental health reforms and human rights using a classical liberal model, while neoliberal forces push to privatize and defund social services, creating a perfect storm of abandonment. There’s renewed conversation about this risk in the UK, where efforts to demedicalize depression and other mental health issues may inadvertently align with right-wing politicians seeking to defund NHS mental health services. Can you elaborate on the politics of this from both the left and the right, and how we might critically navigate the existing system without inadvertently supporting defunding and privatization?

Neil Gong: In the 1960s, many critics of psychiatry focused primarily on a negative liberty model, where the key idea of freedom was ensuring people weren’t controlled by external forces, whether by the state or others. This concept of freedom was mainly about avoiding any external coercion. However, there’s another aspect of freedom, which involves ensuring that people have the capacities and resources, such as education, healthcare, and safety, to act freely.

Many civil libertarians emphasize negative liberty too much, overlooking the need for positive liberty. For instance, they might team up with conservatives to defund hospital systems without considering that these same conservatives won’t fund community systems either. This lack of foresight leads to a dynamic where well-intentioned reforms result in neglect and inadequate resources for those in need.

We see similar dynamics in attempts to decriminalize drugs. Critics fail to anticipate that without supportive infrastructure, these reforms can lead to further neglect. Navigating this issue requires recognizing the need for both negative and positive liberties. We must be critical of existing systems while ensuring that reforms include provisions for adequate support and resources, avoiding the trap of merely defunding and privatizing services.

In California, we saw Proposition 47 turn meth and heroin possession into misdemeanors. The idea was to release some prisoners who were incarcerated for drug offenses into the community and build up a community support system. We managed the first part but didn’t adequately follow through on the second. Building a robust community system is expensive and logistically complicated. After neglecting treatment infrastructure for so long, suddenly finding or building facilities, training new staff, and determining appropriate models is a massive challenge. In a neoliberal model where nonprofits contract with the government, figuring out contracts adds another layer of difficulty.

As a result, we often end up with compromised positions: a bit of decriminalization and a bit of civil liberties, but only in the negative sense—not in the sense of providing positive rights for people. This is a significant danger, as Peter Sedgwick pointed out in PsychoPolitics long ago. While we might philosophically question the language of mental illness, believing it to be too biologically loaded, that medical language is often what allows people to demand resources from the state.

Justin Karter: To stay on the policy front, you offer several concrete recommendations in the second half of your book about changes that could improve mental health care for all socioeconomic groups in LA. How can policymakers start to address these issues? What do you think is the best first step here?

Neil Gong: I’m not sure of the precise best first step, but I’ll tackle two dimensions: community care and institutional settings. From what I observed, people often received treatment based on the sector they were in—public versus elite private—rather than their specific needs. For example, I saw people in housing-first, harm-reduction settings who could benefit from much more. “More” could mean traditional treatments and therapies, but also access to vocational training or education.

We need to ensure that housing-first programs don’t become models of “tolerant containment.” They should provide housing along with a range of services, from harm reduction and peer-based support to various clinical settings. If people want residential rehab, that should be accessible too.

Conversely, I saw people in elite care settings who could benefit from a harm-reduction model, which is less prevalent in these private settings. Family members often resist the idea of allowing continued drug use, making it harder to implement harm reduction. However, individuals in elite care could benefit from the lighter touch seen in the public sector, feeling safe and then choosing their next steps from there.

Turning my attention to the more institutional side, we’re at a very interesting moment in California. California often serves as a bellwether state for the rest of the country, so what we see here might be echoed elsewhere. There is a movement to “bring back the asylum,” with the expansion of care courts—a novel mechanism for court-ordered treatment—and the recent passing of Proposition 1, a $6 billion bond measure. This measure will fund some housing as well as locked residential facilities.

The current debate is very polarized, often framed as pro versus con, yes versus no, and centered on civil liberties. It’s crucial that civil libertarians fight to ensure people’s rights are respected. However, what’s missing from many conversations is a focus on the quality and type of services that will be available in these residential settings. We know that poorly implemented coercive care can backfire tremendously, but there are times when it may be the only way to save a person’s life. These are true statements that we need to be able to hold in tension.

One of the key tasks we need to undertake is building up our voluntary care sector to ensure that very few people ever find themselves in a situation where coercive intervention seems necessary. As new measures are rolled out in California, we must focus on harm reduction. We need to ask: how can we make the unfortunately necessary aspects of coercive care less harmful?

Two ideas I’ve been focusing on involve incorporating peer perspectives and redesigning procedures. First, we need to really focus on peer perspectives regarding psychiatric holds, long-term residential care, and conservatorships. We should gather input from those who have experienced these systems to identify which aspects have been damaging, which have been helpful, and what can be changed productively. For instance, we could involve former patients in designing less alienating psychiatric wards. Researchers like Morgan Shields, who have done great work on the lived experiences of inpatient care, provide valuable insights that should be integrated into our system redesigns.

Second, we need to improve procedural justice in care courts and conservatorship hearings. Even if a person loses their case, it’s crucial that the procedure is seen as legitimate—that their voice was heard, taken seriously, and considered in the outcome. Ensuring that people are treated with dignity and that their input influences decisions can reduce the harm associated with more institutional approaches.

These steps can help mitigate the negative impacts of upcoming changes, making coercive care more humane and respectful.

Justin Karter: One of the goals in your book is to humanize those often dismissed as “sidewalk psychotics.” What do you hope readers take away from your book in terms of changing their perceptions of individuals experiencing homelessness or serious psychiatric disabilities? To that end, could you share how your fieldwork changed your own views?

Neil Gong: As I mentioned before, it’s crucial that we all consider these issues through different lenses. People often approach these topics from various perspectives: seeing them as abstract policy issues, disliking the presence of homeless individuals in their neighborhoods, or feeling frustrated with a loved one they wish they could force into care. These are, of course, stereotypes, and we must also consider the perspectives of those who have experienced trauma from forced care.

What I aim to achieve with this book is to present the voices of all these different people, to hold their perspectives in tension, and to take them all seriously. By doing so, I hope to foster a more nuanced understanding and encourage readers to reconsider their perceptions of those experiencing homelessness or serious psychiatric disabilities.

One thing I hope readers take away is the ability to empathize and walk in someone else’s shoes for a bit. For example, when I have guest speakers who are peer advocates come to my class on the sociology of mental health and illness, it often surprises students. A speaker diagnosed with schizophrenia might be far from the stereotype students have been exposed to; they’re involved in advocacy work, running organizations, and so on. This experience can be mind-blowing for students whose only idea of someone with a psychotic disorder is a stereotype of a person on the street.

I hope that by hearing these stories, readers can move away from viewing people as “the other.” By presenting personal stories alongside my analysis of the systems, I aim to humanize individuals while providing a sociological perspective. Through my fieldwork, I’ve had my own assumptions overturned. Talking to people and hearing their profound insights about personal experiences or inequality in America taught me a lot. I learned from service users, clinicians, and even random folks I met on the street.

However, there were also people I struggled to relate to. Despite my efforts to engage sensitively and non-judgmentally, some aspects of their experiences were beyond my understanding. Readers of the book might also find forms of deprivation and trauma that can’t be fully communicated through reading. Some altered states, like psychosis, are mysterious and challenging to understand, which has led me to rethink my own theories about it.

This has taught me to always remain humble. I hope readers, whether they are family members, service users, clinicians, or concerned citizens, can embrace this humility. We don’t always know what’s going on or what will work best, so we need to be humble about our own opinions and generous towards others trying to do the right thing, even if their efforts don’t always seem helpful.

***

MIA Reports are made possible by donations from MIA readers like you. To donate, visit: https://www.madinamerica.com/

He asked if there was a stop to time. Does time have a stop? But now it seems that time itself has run out of time. It can only repeat and become more and more obviously dead. The dead will drop away of it’s own accord. Just don’t get mixed up with the dead. Almost everything is dead, except you, the inside of you. Feeling, creative nihilo. It comes alive only in absolute freedom. The nearer to freedom the harder it is to bare. Complete freedom is the only freedom. It’s so alive that it cannot move, yet moves everything.

Report comment

The Gilded Age has fully returned: a world of extreme haves and have nots. But calling it The Age of the Boiling Frog I think would be a more accurate way of describing what’s happening today.

Tragically, I don’t see a cure for indifference when so many people are faced with trying to survive economically themselves.

Report comment

The whole idea of paternalistic care is itself violence, domination. Who is to parent another free human being in a free society? Parent implies love, otherwise it is violence. But love cares, and care acts. This is the problem. We do not care about other people’s suffering and therefore don’t love, don’t act, and the resulting human carnage is swept up by mechanical system called psychiatry and psychopharmacology – an unfeeling, unintelligent, unenlightened, fraudulent grift. The psychiatrist may not realize they are nothing but agents of social violence but this is exactly what they are.

Mental illness is basically the result of a society that lacks love and health. When love is forgotten, the world goes mad, and the proof is in the pudding.

Report comment

I agree with this sentiment

Report comment

There is only an inward and outward because the outward, which is other human beings including ourselves, are in conflict. If that conflict ceased there would be no inward or outward at all, and in fact there isn’t – there is only consciousness, within which everything happens, so everything IS consciousness. There is no outside of consciousness for consciousness, so is there an outside to consciousness at all? For whom would it be anything if not for consciousness? But the outside world is actually created because the other is violent towards you, and you are violent towards another, not just physically but in the form of judgement, domination and criticism, and this violence separates you, so they become ‘outer’ to you, even though they are in you, in your consciousness, your one world, your one life, the only thing that you are. Of course if they are a nagging boss you won’t feel like they are your very own life and consciousness because violence alienates, which means separates. So this separation is both real and unreal. We make the illusion real for us and actually cause, create separation.

The idea of a me is an illusion, and the same illusion as the idea of the other. How can someone be other when they are your very consciousness? In the one mundane sense they are only happenings in your consciousness, but in another, deeper sense, your consciousness is the whole consciousness of humanity, and your brain is an apple that fell from the vast tree of humanity therefore is the whole of humanity. What in your mind is not drawn from the vast totality of social historical experience, both your own and the collective experience of humanity? The thinking mind is composed entirely of social forms and images drawn from social experience. Everything in thinking is conditioned by society and made up of social historical forms that have accumulated as the human totality. So the thinking mind is nothing but these social historical accumulations, this totality. So this consciousness is the consciousness of the human totality, but your consciousness is the whole consciousness of humanity in many and deeper senses still, but you’ll have to peel this onion yourselves because it will take forever to go into, but the onion is not hard to find because you are this onion! It is your own mind.

It’s an illusion that anything in human reality is not the whole of humanity – that is like saying a part of the body is not the whole of the body, but in truth the part is a mere conceptual abstraction: there is no part, only the whole, and the mind breaks it down into fictional parts. So one skin cell is the whole human body AND the whole of humanity AND the whole of nature AND the whole of the Universe because all these unreal conceptual divisions are to plot out the infinite and break it up so we can discuss it. All of us are the infinite.

This is more interesting to me then Jo Biden or even Donald Trump. Donald Trump always looks like he is being electricuted. But he is the whole of humanity and his soul has done an admirable job in creating a unique learning situation for the whole of humanity. That’s what a person is – a flower of nature expressing pertinent truths. We are al manifestations of the whole truth of the Universe, and that truth is revealed only through understanding ourselves and through understanding ourselves, understanding all selves. It is not that we know all selves, but we understand the fundamental structure of reality, and the only reality anyone can ever know or discuss or grasp is our very own conscious reality, which is our consciousness, not some divided ‘reality’ which is merely an intellectual concept. Consciousness is all there is. The world is a mere idea and so are you and me.

Report comment

Such important information and insight. Thank you for your compassionate work. Giving a voice to the silenced, discarded, and erased makes a difference. Understanding lived experiences is critical to reducing individual and societal suffering. We need radical systemwide changes to reverse the current trajectory of policies and practices that undermine freedom, safety, and equality. Your statement about the young man who felt trapped in a place where his presence was voluntary should be highlighted for emphasis of understanding. Maintaining a power imbalance with coercive control involves forcing targets into unresolvable dilemmas regarding life and survival. The resulting loss of autonomy serves the ones in power in many ways. It’s a trap that can’t be seen. It misplaces cause and blame. It creates they very problems it claims to be helping. It reinforces conformity and compliance to rigid beliefs. It’s written on the warning sign that’s staked on the slippery slope on which we live. Compassion is the only way off

Report comment

I agree. Depriving adults of personal agency and bodily autonomy just replaces one hell with another. Coercive control (infantilization) creates many of the same problems that caused people to go over the edge in the first place.

Report comment

Exactly. You captured nicely what I was trying to say with far too many words lol.

I agree with the boiling frog analogy. I believe death by a million paper cuts fits as well

Report comment

🙂

Report comment

Thank you for your careful and compassionate examination of a very complex problem.

Report comment

Ah yes capitalism.

Report comment

Why do we keep distancing ourselves from people? Governments are people. Corporations are people (although the Law has decided otherwise). Systems are people. Policy writers are people. Economists are people …. It is these people who have decided which morals, which ethics that they value as important, most important. Regardless of Mission Statements and regardless of Philosophies, which are so well managed and put in print for all your the world to see, who actually lives by such values? Who actually puts these publicised values into action?

Struggling to think of anyone….?

Report comment