While the 1960s and ‘70s saw major upheavals in culture and knowledge, the 1980s would turn out very differently. Riding a wave of reactionary politics, Ronald Reagan was sworn in as the 40th president of the United States on January 20th, 1981. While it is true that part of this wave was rising up against the economics of the “liberal consensus” and Keynesianism, it really owes its victory to the revolt against changing cultural norms.

By 1980, critical discussions on race, gender, and class had spread across the country. Community and workplace organizing was working to beat back the oppressive past. But that pushback came with conflict, and that created internal conflict in many Americans who would saw themselves as apolitical or “moderate”. This tension and internal conflict was masterfully used by students of Edward Bernays.

Much like Nixon in 1968, the Reagan Campaign would message the need for “Law and Order”, hard work, and a belief in American Meritocracy (AKA “Just World Theory” or “you get what you deserve”). At first, the realms of drugs and addiction were not a major part of this dynamic. They rarely spoke of drug users directly. Instead, they relied on dog-whistles, like the “Welfare Queen”, that could vilify people of color and the poor at the same time. While many could infer the existence of drug use in these caricatures, they would not be called out by name.

Partly because even Nixon himself knew that addiction could strike (almost) anywhere. It was better not to tempt fate by accidentally igniting empathy instead of outrage. That is, of course, until Reagan found himself losing support.

After his first year of tax cuts for the wealthy created a looming recession, the “honeymoon period” support, measured by approval ratings, started to drop. In 1982, as a response to this (much like Nixon before him) he launched a campaign against the “scourge” of drugs. He would speak of the need to help those suffering, while not increasing spending for diversionary programs or treatment.

Instead, Reagan pumped billions into the policing and criminalization of drugs and drug users. In order to continue his public relations approach to the Drug War, he handed off the public-facing duties of the operation to the First Lady, Nancy Reagan. This would eventually culminate in the famous “Just Say No” crusade. Even with all the knowledge we had gained in the decade after Nixon’s first salvo in the War on Drugs, America was going back to the front.

The Crack Epidemic

Interestingly, Reagan launched this campaign at a time when drug use and addiction were at all-time lows, further evidence that the expansion was less about actual drugs and more about publicity and politics. However, he found willing partners like LAPD Chief Daryl Gates who infamously said that “casual drug users should be taken out and shot”. Gates compounded that infamy when he created and implemented the Drug Abuse Resistance and Education (D.A.R.E.) campaign.

D.A.R.E. had never been researched prior to introduction into schools but had a message that was a perfect match for the “Just Say No” campaign. We now know that DARE was responsible for expanding the reach of drug misinformation to Gen X and Millennials. Even with all the misinformation, only 2.6% of Americans thought drugs were the nation’s number one problem in 1985. Then, to paraphrase Michelle Alexander, “they got lucky”.

The same year that was taken, “crack” cocaine was showing up on the streets. The psychoactive chemical compound found within the drug was no different than what was being fashionably used at discos in the ‘70s and boardrooms in the ‘80s. The problem was that regular cocaine was extremely dangerous to smoke. People learned that simply combining regular powder cocaine with baking soda, through heat (“cooking”), crystalized the compound. The cracking sound when the crystal was formed gave the drug its name.

In this form, it was much safer to smoke (from a standpoint of immediate harm). This change in route of administration allowed the drug to enter the bloodstream, and break the blood-brain barrier, more quickly and more efficiently. The intensity of the experience was not due to a change in the chemical, making it “more addictive”. It was simply a more effective way to use the drug.

With “crack” usage expanding over the next few years, along with nightly news coverage of associated crimes, the percentage of people who said America’s number one problem was drugs rose to 64% in 1989. During this time, the Reagan administration was able to escalate policing in communities of color, spend billions to militarize the police, and execute paramilitary actions across Central and South America.

A combination of growing panic about “crack” and an administration ready to exploit those fears cemented a “tough on crime” consensus within both major American political parties. This consensus led to what we know today as the “Crack Disparity”. As we discussed, “crack” was not chemically different than powder cocaine. It was the same substance, with inert baking soda added. Yet, the sentencing for drug violations regarding “crack” cocaine was more strict by a factor of 100 (e.g., people caught with 5 grams of crack were punished as if they held 500 grams of cocaine).

One major disparity between the drugs was that poor Black folks were largely used “crack,” while rich White folks mainly used powder cocaine. And while the 2010 “Fair Sentencing Act” reduced the disparity, the issue remains.

In spite of incarceration rates for drug crimes skyrocketing, drug use and addiction rates remained pretty steady:

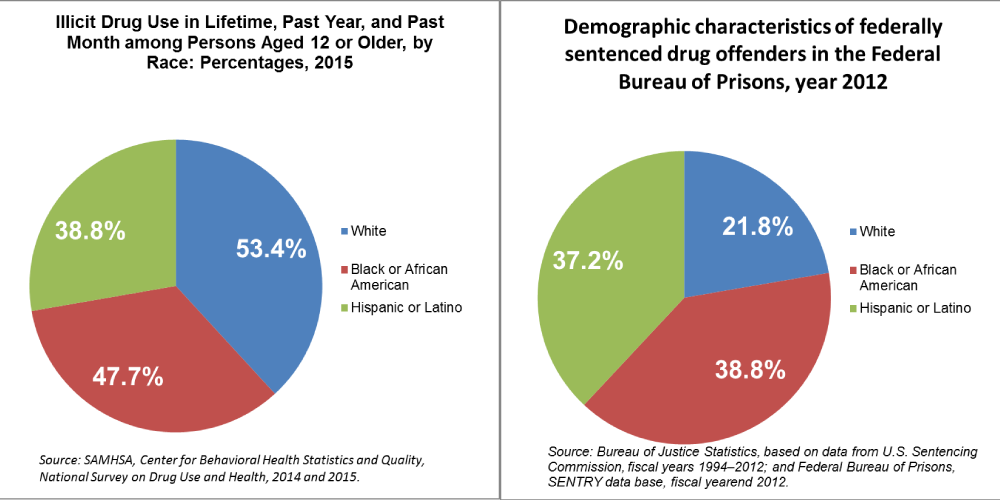

Many contend, with good evidence, that the main goal of the Reagan Drug War was to reify the ever-present, cultural image of the dangerous Black drug addict for a new audience. Nonetheless, the truth is that White people have always used more drugs than Black people (and other races as well), while Black people are incarcerated for drug-related offences at many times the rate of White people:

With everything that we learned about drugs in the 1970s, there was no reason for this to occur. We had learned that the endogenous addictiveness of drugs was not inherent. We had learned that those people who were addicted were not “out of control”, but were instead suffering from some other trauma, instability, or insecurity.

All these ideas that were used as a foundation for tough crime laws were repudiated, yet those ideas continued on. And not only did they continue in the social and political spheres, but in the realm of addiction treatment itself.

Betty Ford

In many ways, the findings of the 1970s were more applicable to addiction treatment than policy. The main model at the time, “Twelve Step Facilitation” (TSF), was based in the same temperance movement ideologies and beliefs that were instilled in the 12-step “rooms”. As had been thought for 200 years, addiction was a “chronic, progressive…uncontrollable disease of the brain” which necessitates the model of treatment founded by Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), at the very least, lest the sufferer die. As we saw in Part 5, this model of addiction was, bluntly, false.

Yet, the industry grew while maintaining that usual standard. In fact, the hegemonic Hazelden (which was discussed in Part 3) had found a famous competitor in the new “Betty Ford Clinic”, launched by the former First Lady, Betty Ford. Ms. Ford had dealt with alcohol and drug addiction while in the White House with her husband, and later found recovery in AA.

As part of her 12th Step, wanting to expand the reach of AA and TSF treatment to help those suffering from the disease, she used her power and wealth to start the new clinic. With the clout of the former first lady’s name, the new clinic rose in fame and acclaim.1

While AA had risen in approval since the Marty Mann campaigns of the ‘30s, ‘40s, and ‘50s, actual treatment still held stigma and a lack of social acceptance. New films and television depicting the traditional treatments and models found in Hazelden and Betty Ford, such as Michael Keaton’s Clean and Sober and James Woods My Name is Bill W., helped to teach America what their system of addiction treatment and recovery was all about. In fact, you would be hard pressed to find someone who has gone through traditional treatment and has not seen both of those films while in treatment.

Not only did this allow for acceptance to grow, but the industry itself grew into a $2 billion behemoth by 1995 (now $42 billion). Yet its success rate hasn’t grown beyond 30%, even for those who actually complete the program. Moreover, 70-80% drop out of treatment within 6 months!

Conclusion

Once again, defeat was snatched from the jaws of victory. While the treatment industry could have reformed their foundation around the new knowledge from the ‘70s, it instead doubled down. Lee Robins’ study would be forgotten until the mid-2000s, right before her death. “Rat Park” replications would be imperfect, allowing researchers to attempt to debunk the whole premise. Stanton Peele would be presented as the heel during an interview with Oprah. As for the Sobells, they had to flee the country for a decade after facing threats and incessant harassment.

Unfortunately, America was not quite ready for the major changes necessitated by the advances in our understanding of addiction. Still, there was something happening during this period in history that would force people to grapple with our inadequate framing and structures. It was horrible, deadly, and yet oft forgotten. It took Reagan four years into this crisis before he would even mention it by name. Yet, it came with a (very thin) silver lining in that it helped to create and grow what would become known as “Harm Reduction”.

It was HIV/AIDS.

Editor’s Note: All blogs in this series are available to read here.

Reagan pumped billions into the policing and criminalization of drugs and drug users. In order to continue his public relations approach to the Drug War, he handed off the public-facing duties of the operation to the First Lady, Nancy Reagan. This would eventually culminate in the famous “Just Say No” crusade.

Ah, sweet memories.

My friends in the “marijuana movement” used to point out how rude Nancy’s slogan was, and remind people that the proper response would be “No THANK YOU.”

Report comment

These are brilliant articles showing how drug policy is used by politicians to garner votes while the real causes and solutions to problenatic drug use are ignored.

Report comment

Well, John. If our politicians actually did do something serious about addiction, they wouldn’t have anything serious to campaign about during their following election campaign seasons, now, would they.

Report comment