Hello and welcome to this Mad in America podcast. My name is Robert Whitaker, and I’m happy today to have the pleasure of speaking with Joanna Moncrieff.

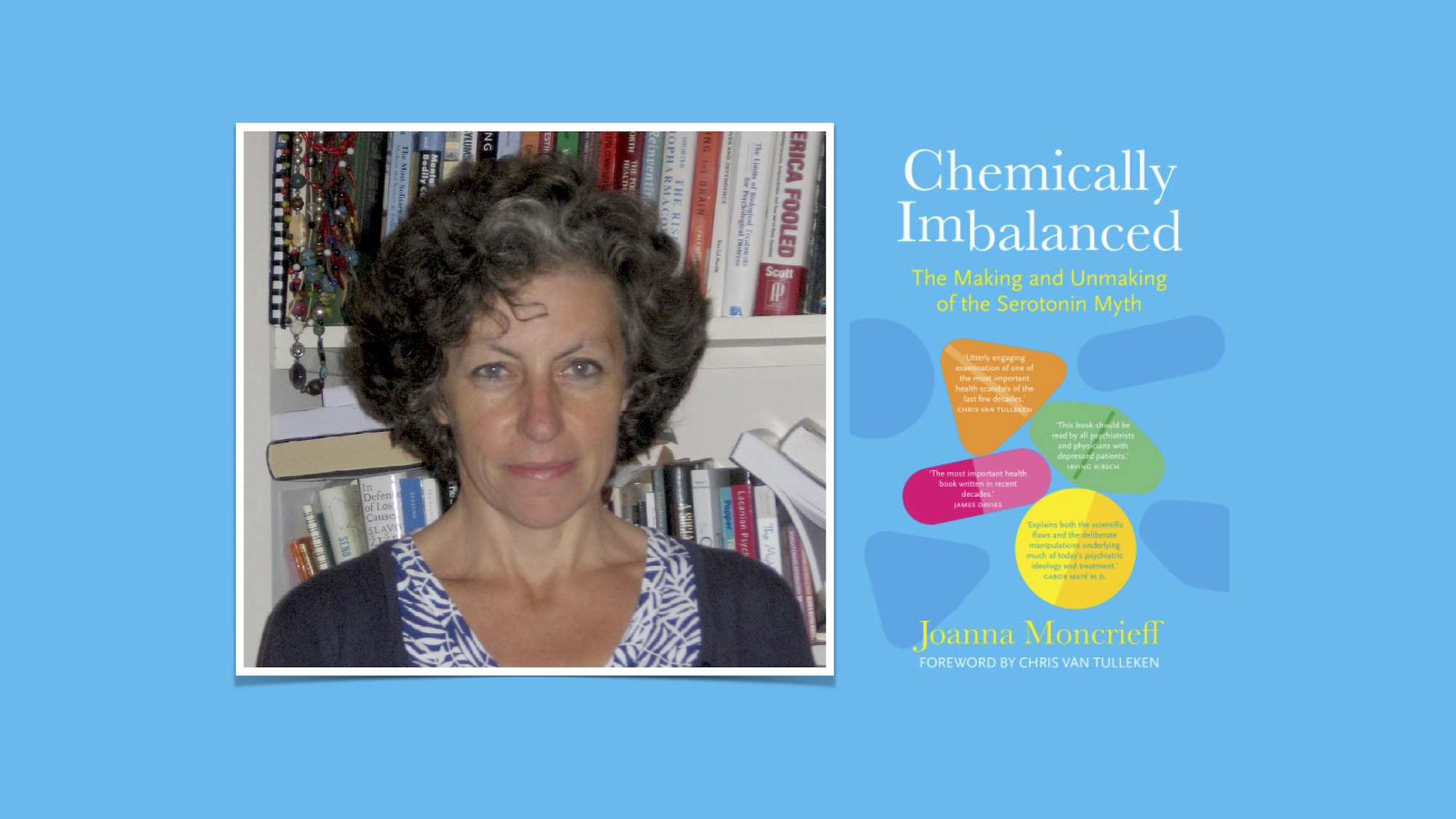

Dr. Moncrieff is a psychiatrist who works in the National Health Service in the United Kingdom. She is a Professor of Critical and Social Psychiatry at University College, London.

In 1990 she co-founded the Critical Psychiatry Network, which today has about 400 psychiatrist members, about two-thirds of whom are in the United Kingdom. From my perspective, the Critical Psychiatry Network has been at the forefront of making a broad critique of the disease model of care. Without this network, I don’t think that critique would be anywhere near as prominent or as sophisticated as it is today.

Dr. Moncrieff is a prolific researcher and writer. Her books include De-Medicalizing Misery, The Bitterest Pills: The Troubling Story of Antipsychotic Drugs, and The Myth of the Chemical Cure.

Her latest book is titled Chemically Imbalanced: The Making and Unmaking of the Serotonin Myth. This book in many ways is a follow-up to her 2022 paper which looked at the serotonin story and concluded that there was no good evidence that a serotonergic deficiency was a primary cause of depression. It caused quite a furor within the media and in psychiatry.

The transcript below has been edited for length and clarity. Listen to the audio of the interview here.

Robert Whitaker: Joanna, it’s such a pleasure to have you, thanks for being here.

Joanna Moncrieff: Thank you for having me, Bob.

Whitaker: We will be talking about your book, but I’d like to know the path that you took to become a critical psychiatrist. I believe you were in medical school in the late 1980s. So, my first question is, why did you want to be a psychiatrist?

Moncrieff: I’m afraid to disappoint people that I don’t think there’s been much of a character arc. At medical school, I was already probably more interested in philosophy and politics than I was in medicine, and so I gravitated to the areas of medicine that were most politically and philosophically fertile and controversial. That was inevitably psychiatry. I was reading people like Thomas Szasz and R.D. Laing already when I was in medical school.

I went into psychiatry after I finished studying, so I was already primed to look at psychiatry through a critical lens. But then when I started as a junior doctor working in the very last days of the old asylums, I was really pleased that I had that time because it was really interesting. I think now the asylums have gone, it’s actually more difficult to understand the psychiatric system than it was in the day when everyone was together in these big institutions.

So I was working in these old institutions in their very last years as they were all crumbling around me. Everyone in those institutions was on multiple types of psychiatric drugs. I was very struck by the difference between what it said in the textbooks, which was we’ve got these wonderful new drug treatments introduced in the 1950s that revolutionized psychiatric care, everyone gets better now and leaves the asylum and that’s why they’re shutting it down. The reality was people were shuffling around wards obviously zombified, obviously heavily sedated maybe less symptomatic but not really better and certainly not recovered. I suppose that confirmed my suspicions that psychiatry was not as it was laid out in the textbooks.

Whitaker: That’s interesting for two reasons. One is that it seems that the disease model of care that was being promoted, at least in the United States, starting in the 1980s and 1990s lacks any philosophical conception of what it means to be human and sense of our natural range of emotions. It’s so barren in that sense.

But the second thing you’re speaking about is that you had clinical experience that didn’t jibe with the story that was being told. When were you in medical school in the UK, were they teaching the DSM III disease model, or did you hear a different story about what causes depression?

Moncrieff: When I was in medical school we were taught, as we’re still officially taught now, the biopsychosocial model of mental disorders. But what was different then compared to today is that we were taught to do a formulation. You took a long history from someone and you went into their childhood, developmental and personal history. Then you put everything together and you had to summarize relevant biological factors but also relevant psychological and social factors.

Although there was already a very strong biological current in psychiatry, at that time there was still the strong influence of psychotherapy, psychoanalysis, and social psychiatry. I would say much more so than today when all we have is please give us the diagnostic code for this patient and then the treatment supposedly follows from that.

Whitaker: You really were being taught to understand the person’s life at the beginning. The context of their life.

Moncrieff: Yes.

Whitaker: So now you go out and you’re in the asylum or mental hospital. Did you find that the patients in any way fit neatly into these different diagnostic constructs?

Moncrieff: Absolutely not. That’s as well as discovering how the narrative about the drugs didn’t fit reality, the diagnosis was probably even less congruent. I would say even for a very mainstream psychiatrist it’s surely obvious that we’ve got these rigid boxes and we’re trying to squeeze people into them.

We’ve got a few sort of crude labels and we’re trying to squeeze this huge variety of human trouble, confusion and distress into these narrow boxes, because then what you see is only the box. You see the box, you see the label and that’s what you treat, or that’s what you’re supposed to treat rather than trying to help a person with their individual difficulties and their idiosyncratic ways of responding to life. What you’re trying to do is treat a label as if everyone who has this label of depression has exactly the same thing going on.

Whitaker: It’s interesting that you’re going through this in the 1990s in your own experience. Here in the United States, we were hearing this story of extraordinary advances. Prozac fixes the chemical imbalance in the brain. We had new atypical antipsychotics which is a story of great medical advances and fits into a larger narrative of the advance of medicine in the 20th century. Yet you co-founded the Critical Psychiatry Network. How did you and others find each other and what did you see as your mission?

Moncrieff: I was aware when I was still a fairly junior trainee psychiatrist that there were other people who were similarly critical of the mainstream medical model. When I got a job at the Institute of Psychiatry I was working with a couple of colleagues, and a couple of other trainees who were like-minded. We set up a little reading group and we read R.D. Laing and Thomas Szasz so that’s how it started. Then we thought we’d invite a few people to come and speak to us because there was a nice lecture theatre and we could get them to come along.

I emailed Thomas Szasz on the off chance that he might be visiting the UK, and he was. We had Thomas Szasz speaking in November 1997 to a packed audience, so that was interesting.

Then we got together with people from other parts of the UK and what brought us together initially was the Labour Government’s decision to review the Mental Health Act. They commissioned a big and thorough report led by a lawyer. It was quite a good report on the Mental Health Act which fundamentally questioned the whole premise of mental illness as a basis for incarceration. One of the options it put forward was that coercive treatment and hospitalization should be based on capacity rather than a supposed diagnosis of mental illness. That was in the end rejected because I think it was just seen as being too big a change and too complicated, but it was interesting and we fed into that process. We put in a report to the information collecting part of that process of review.

Whitaker: There were some political winds that lent you some support within society for what you were doing. It is interesting that the critical psychiatry group managed to survive within British psychiatry. Whereas in the US, people who broke out of the system were really pushed out. They had a hard time staying in the system.

Two things Joanna, how would you describe the critique that the network advanced? How well was it received and why did you survive in the UK whereas here people who broke with the conventional wisdom had a tough time staying in their jobs and not being sort of dismissed by the media as cranks?

Moncrieff: I was reflecting on this when I wrote my recent book. My experience when I was a junior psychiatrist and a medical student was that psychiatry was really quite a supportive forum for debate. Then even mainstream biologically inclined psychiatrists used to welcome debate. They were not too defensive and able to see other points of view.

When I invited Thomas Szasz to come in 1997 to the Institute of Psychiatry, the heartland of biological psychiatry in the UK, the audience was packed and some very mainstream biological psychiatrists showed genuine interest in his point of view. I would say that in the UK that has changed somewhat over the last few years. It feels like a much less comfortable place to have a debate nowadays and it’s just less possible to have debate.

I mean even today there seem to be far fewer critically minded psychiatrists in the US, at least that I know of, because actually every now and then I come across someone who’s been doing amazing work. Helping people withdraw from antidepressants in some little place I’ve never heard of but hasn’t linked up with us. I think that reflects what you say that being outside the mainstream in the US is much more difficult, and you just really need to keep your head down.

Whitaker: What did you see as the impact of the Critical Psychiatry Network over the past 20 years? Have you managed to get this critique into the mainstream literature? Can you just talk about the accomplishments of the network?

Moncrieff: The members of the network have published quite a lot. I’ve published but other people have as well. Phil Thomas and Pat Bracken who were leading members when we got started published books on post-psychiatry as well as scientific papers. Duncan Double’s been quite a prolific publisher as have Hugh Middleton and Sami Timimi.

I think that’s helped to build up a body of influential knowledge that’s critical of mainstream approaches to mental health and psychiatric care. I think it’s been important just to create that and have a body of literature that people can refer to. I think it’s also been important for the rising survivor movement to be able to reference psychiatrists who agree with them and who share their criticisms of the mainstream model.

Have we changed care? I don’t know whether we have changed care. I think the survivor movement has changed things facilitated by the Internet. The ability of people now to link up about antidepressant withdrawal, benzodiazepine withdrawal and sexual side effects, has all been put on the agenda by people who’ve been subjected to the harms of these drug treatments and have been brave enough to come out and speak about their experiences and highlight it. But I think knowing that in the background there are professionals who agree with them has hopefully been helpful as well.

Having an alternative perspective available for people to find is so important, isn’t it? There will be plenty of people who still want to subscribe to the disease model, and that’s fine. But what I hope we have now achieved is that people who don’t like that idea can go and explore other ways of understanding their difficulties. There is a different way of thinking out there.

Whitaker: I know from the many people I’ve talked to who’ve re-envisioned their own sense of what was happening to them–I’m talking about psychiatric survivors–that being able to read what you all have been publishing was pivotal for them to remake their own narrative. Often that narrative led to a much better place. It’s been essential, I think, not just in a broad way but to the individual lives of many, many people.

Let’s go back to the serotonin story because it is so critical to the heart of that biological story. Tell us just how did the hypothesis arise, and then how it was investigated?

Moncrieff: It goes back to the 1960s. These new drugs are coming into psychiatry which starts with what we now call antipsychotics, which are given to people with psychosis or who are diagnosed with schizophrenia. Then people start thinking, well, if we’ve got a drug for psychosis that looks as if it’s a bit helpful, maybe we can find a drug for depression.

They start throwing various drugs at depression, drugs that are completely different from each other. They try out Iproniazid and Isoniazid, which are drugs that are being used in TB and are almost certainly amphetamine like substances with an amphetamine-like profile of side effects, including psychosis and insomnia. But then they also try out some chlorpromazine-like drugs, so those are really sedating tricyclic antidepressants.

In the middle of all this experimentation, people start to think, okay, we need some theoretical basis for this and start to speculate on why and how drug treatment might be useful in people with depression. That’s where this idea comes up, that maybe depression has to do with some abnormality in brain chemicals that is being corrected by the drugs that are being given. The first interest is actually in noradrenaline because amphetamine, which, although it was not often referred to as an antidepressant was widely being prescribed to people with depression, was known to stimulate noradrenaline.

Noradrenaline was the chemical that sparked interest most back in the 1960s, but serotonin was also suggested to be relevant to people with depression. This idea that there’s an imbalance and abnormality, particularly a deficiency of chemicals such as serotonin and noradrenaline, was articulated first in the 1960s. It’s then actually researched in a big project funded by the NIMH in the US in the 1970s which almost certainly finds nothing because it doesn’t publish anything anyway.

By the 1980s, David Healy is writing to say, this theory is dead in the water. This hypothesis that depression is caused by a chemical imbalance, it’s dead, it’s over. Then, probably the same year it’s picked up by Eli Lilly, the makers of Prozac, and other pharmaceutical companies who come along with their SSRIs, and they breathe new life into it and recruit this idea, which has already been disproven, to market antidepressants.

The reason it’s so useful, so vital to them is that the use of drugs to numb and sedate people with emotional problems had got a really bad reputation by the end of the 1980s because of the mass prescribing of benzodiazepines. In addition to the revelation that benzodiazepines were just as dependence-forming as barbiturates, even though they had been marked as being free of this complication. With benzodiazepines, it’s difficult to pretend that you’re doing anything other than just drugging people’s misery away temporarily.

The pharmaceutical industry wanted to put a line between benzodiazepines and their new range of drugs. They marketed this new range of drugs as SSRIs. Firstly, they chose depression rather than anxiety, which had been the main condition for which benzodiazepines were given. Secondly, they marketed them as disease-specific, a disease-targeting treatment and as something that targeted an underlying abnormality.

They told people that depression was caused by a chemical imbalance and that you need one of our new drugs to put it right. That’s why the idea was so important at that period of time to the pharmaceutical industry, and that’s why it was disseminated all over our culture so that everyone came to believe that it wasn’t just an idea, it wasn’t just a theory, it was a proven fact.

Whitaker: Here’s the interesting thing. The NIMH had one of their investigations, and they published in 1983 and said there’s no evidence that low serotonin is a cause of depression. I think it was in 1998 that the American Psychiatric Association’s textbook said the monoamine theory of depression just hasn’t panned out. Yet, if you would have been in medical school in the United States in the 1990s, they were teaching the low serotonin theory of depression. New psychiatrists were learning that that was a fact. I don’t know how it was in the UK, but I think that so many GPs and psychiatrists came to believe that story.

Moncrieff: I remember my training, and we were taught that it was a theory, and we were taught that there was evidence for it and evidence against it, like the dopamine theory of schizophrenia. Having said that, we had some very good teaching by a pharmacologist, who wasn’t a psychiatrist, so expert teaching in different places varied. But if you look at textbooks, they usually refer to it as a theory. They don’t often say explicitly that it’s been proven. But then you’ll see something like a table with causes of depression which includes serotonin imbalance or neurotransmitter abnormalities or something similar. There was always an implication that there was more evidence than there actually was, even if you weren’t explicitly told this has definitely been proven.

Whitaker: I understand why the pharmaceutical companies wanted this story, but why was psychiatry so interested in this story? They promoted it like heck, it became their calling card so to speak ,at least again in the United States. In 2007 I think, there was a press release put out by the APA saying that psychiatrists are experts in fixing chemical imbalances in the brain.

Moncrieff: I think that some psychiatrists really want to believe that depression, in particular, is a proper medical disorder. I think this stems from history and from the fact that psychiatrists were born and started their lives in the asylum system, and then in the 20th century, started to feel that being associated with the asylums and with people with chronic, severe mental health problems such as so-called schizophrenia, was a bit stigmatizing.

They tried to develop an outpatient practice and that takes off in the mid part of the 20th century. Depression was one of the less serious conditions that they chose to label that they came across in outpatient clinics and community services. That helped them to develop a clientele of people who were not people with chronic, severe, psychotic conditions, but people with less severe conditions. That was partly because of the stigma, but also probably also partly because of the money.

Thinking about it, it’s different in the UK because it’s a nationalized service, but in a commercial system, there’s not much money to be made out of people with chronic, severe mental health problems, but probably quite a lot to be made out of people with less severe mental health problems.

Whitaker: There is a sense, I think, that the profession became believers in their own propaganda. In 2009 you wrote The Myth of the Chemical Cure and so you understood a long time ago this had not panned out. So why did you do the research that led to your 2022 paper if it seemed like this had been debunked? Why make that exhaustive effort with Mark Horowitz to do it?

Moncrieff: I wanted to do it because there was nowhere to point to, to say that this has been debunked. You have to say, oh, well, there’s a reference in this textbook that says that it’s not supported or a reference here. But there was no substantial paper or piece of research that actually said, look, there really isn’t any good evidence for this idea. That’s what I wanted to do. I wanted to bring together all the recent strands of research into the links between serotonin and depression in one place. To take an overview and come to a conclusion.

Whitaker: What you did in that book, of course, is you went through the history of research and the different types of efforts to see if people had low serotonin because there are different kinds of experiments. They look at metabolite levels and that sort of thing. No matter what the method, you found that there never was a finding that really supported the theories. Is that fair to say?

Moncrieff: None of the various areas of research that have looked at it found any consistent or convincing findings.

Whitaker: First of all, the media response. Your paper elicited a huge media response and I think it had quite an impact on the profession as well. If you look at the metrics for studies that are read, it’s quite high up.

Moncrieff: People were staggered, really surprised. I went on one television program and the presenter said it blows your mind that this is not true. It revealed that the general public has been persuaded by all this pharmaceutical industry and medical propaganda that depression has been established to be caused by a deficiency of serotonin. Not that this is just one theory or that there might be a bit of inconsistent research out there but that it was an established fact. That’s what people thought, and so people were blown away to find out that it wasn’t true.

Whitaker: One of the responses by psychiatrists is that this is nothing new. We knew it all along. Well, when they say this, that becomes a story of betrayal. Obviously, doctors have a responsibility to inform the public and their patients of what is known and to get consent for treatments based on what is known. But in essence, they were saying, we didn’t tell this to our patients, even though we knew it. Can you speak to that sense of betrayal by a medical profession towards its patients?

Moncrieff: It’s really shocking, isn’t it? I think the publication of our paper and the public reaction to it was profoundly embarrassing for the profession, because even if they hadn’t been explicitly telling people that depressed people had a chemical imbalance, and we know that lots of doctors were telling people this, and probably still are. But even if they weren’t, they hadn’t stopped people from believing it. They hadn’t stood up when the pharmaceutical industry was flooding the airwaves with this message and said this is not established. This is not proven. You shouldn’t be persuading people that this is the case. I think it was a profound embarrassment.

Whitaker: As you know, on Mad in America, we regularly publish first-person stories. The story that comes out over and over again is how people feel their lives were dramatically changed by that story. Self-identity changed and their use of these medications changed. So often they had very bad long-term outcomes and they really feel their lives were taken away from them in a large way. This wasn’t a harmless betrayal, in my opinion. There is a sense of harm done by telling a story that’s not true, which gets you to take the drug because of your conception of what’s happening to you.

Moncrieff: I really agree with you. I think this has done so much harm. When people tell you about their experiences they will often say, “Oh, initially it was a relief. Initially, it was great to think, okay, it’s a simple problem. There’s some abnormality in my brain. I can take a drug and it’ll put it right”. Sometimes people initially feel a bit better and have a sense of relief and like the idea. But then, as you say, it gets into people’s view of themselves. It changes people’s sense of their identity and it is profoundly disempowering.

To be told that your emotional reactions are being controlled by some processes in your brain that you have no control over. That you have no agency and you’re going to need to go to the doctor and get some pill to tweak. Then, of course, the pill doesn’t work, so you think you’re a biological failure. Even worse than having a biological condition, you’ve got an untreatable biological condition. You can understand how that can set people on a pathway to chronic debilitation and disability. Many stories testify to that.

After I published the paper, one of the frequent questions was, “If we can’t give people antidepressants, then what can we do?” People were quite indignant that I should be criticizing the current view of depression and the current solution to depression without having a perfectly worked-out answer to resolve everyone’s emotional difficulties. But really, what people should be saying is this idea that we’ve had, and this answer that we’ve suggested for it, is incredibly harmful, and actually, if you take that away the world will be a better place for it. Even though that means that, yes, people will struggle with their emotions; yes, we should definitely develop other forms of support, other ways of helping people; but actually just getting rid of that harmful idea would be a very good thing.

Whitaker: The other thing I heard was that Daniel Carlat said, for example, “Well, I don’t really believe it, but I tell people that anyway.” Did you hear that? If so, why is it okay to lie to patients? Why would psych professionals say I lie to them for their own good? Which is basically what that response was.

Moncrieff: He said that. Ronald Pies said something quite similar. Carlat also said that he wouldn’t tell people that it was a serotonin imbalance anymore, but he’d say it was something similar. Back in 2005 or 2006 when Lacasse and Leo published a paper on the serotonin hypothesis which got some media coverage, Wayne Goodman responded. He said that he thought this was really interesting and that the chemical imbalance was a useful metaphor for the idea that depression is a brain-based problem. That I think reveals the whole nub of it, that mainstream psychiatry desperately wants people to carry on thinking that depression is in the brain and that we can tweak the brain in some way to put it right.

They’re very threatened by anything that really fundamentally questions that idea.

That really speaks to my ideas about models of drug action, and how there is such a deep belief in the disease-centered model of drug action that psychiatrists and doctors really cannot see around it. They cannot contemplate that there is an alternative explanation for what drugs are doing.

In the case of antipsychotics and dopamine, antipsychotics clearly create a highly abnormal altered brain state which alters people’s behavior and thinking processes and emotions. That is a perfectly sufficient explanation of how they affect people with psychosis and schizophrenia without having to come up with any theories about dopamine abnormalities.

But many psychiatrists just cannot contemplate seeing their drugs in that way. It just may be too terrible to think that actually what we’re doing is using chemical straitjackets or chemical pacifiers as the barbarian psychiatrists of the past did, because we are new scientific people, we can’t possibly be seen to doing that. Therefore they just blank that out, and all they can see is that it must be some abnormality of dopamine.

Whitaker: Now, let’s go to your book. Can you talk about how even though it’s the making and unmaking of the serotonin myth, you’re really bringing it into what does this mean for how we think about depression, how we treat depression, and what are the opportunities?

Moncrieff: I wrote the book to answer all the questions that people put to me after I published the paper. I was trying to address all these huge questions, like, if it’s not serotonin, then what is depression? If antidepressants aren’t the answer, what is the answer? Do antidepressants work? I was trying to answer all these questions in interviews, and probably not doing a terribly good job. So I thought, okay, I’ll sit down and do a good job of it and answer all these questions properly. That was really the stimulus for writing the book.

That combined with the extraordinary reaction that it provoked from the general public and from the psychiatric profession. I felt this needed to be documented as an example of how vested interests shape what becomes received scientific wisdom, received scientific knowledge. I felt that after the publication of the paper, we saw how knowledge was shaped in action. We saw the psychiatric community coming together to counteract this challenge to their knowledge base and to the message that they put out there. We saw how they came together to defend their point of view, and make sure that any questioning was shut down. I thought that was important to document that process.

Whitaker: I think this is really important. What happened is when the low serotonin theory is debunked, it becomes a challenge to their narrative and the narrative that we formed our lives around. One that they sold to the public. I think that’s why you got such a response. It wasn’t just an element, their whole narrative was collapsing, and of course, that’s quite a threat.

I think you do a beautiful job in the book of achieving your aim. I think it’s really important to understand the response because it was a response designed to defend the narrative and you can see actually the flailing in that response because they actually can’t point to evidence that supports this narrative. That’s their problem, that’s their weakness. But then your book does go into, okay, so if that narrative is wrong, It opens up a new narrative of possibility.

There are two parts to that, the way I see it. One is to just go back to asking is depression episodic, and is it a response to the environment rather than a flaw in your biology. Then also, once you re-conceive depression the way you present it, then the question becomes, do we use these drugs at all? Can you talk about the opportunities that you present in this book that come from re-conceptualizing depression?

Moncrieff: Yes, and I think that’s a really nice way to put it because I’m often accused of being nihilistic because I don’t want to simply offer people a pill or some brain procedure to cure their troubles. But actually, I think re-conceptualizing depression is a very positive and optimistic thing to do. It helps to empower people and give people agency. Also, it actually chimes with our underlying inclinations and beliefs which were deliberately beaten out of us by the pharmaceutical industry propaganda exercises that were dressed up as disease awareness.

People used to understand depression as a natural reaction to bad things happening in their lives. There is tons of research, which is not disputed, that shows that if you’ve been the victim of child abuse or maltreatment, that if you’ve got financial problems and housing problems or relationship problems, you are more likely to have depression, you’ll have an increased vulnerability to being depressed, and lots of other mental health problems as well. That’s how people used to think of depression. If you think of it like that, then it’s clear that all a drug can achieve is to sedate you at best. To temporarily induce a little bit of oblivion that puts these things out of your mind, but it doesn’t help address the situation in any way.

If you think of it like that, it puts the emphasis back on looking at why you are feeling like this. We’re asking the wrong questions. Instead of asking, what is your diagnosis and what’s the correct treatment for your diagnosis? We should be asking, why do you think you might feel this way? What could it be that’s gone wrong in your life, and what could be done about that? That’s not necessarily easy. Obviously, people can be facing really difficult situations that are not easy to change. Ultimately, I think that’s a much more empowering view than being told that the problem is in your brain and you need to rely on the doctor’s magic potion to put it right.

Whitaker: There was a six-year study done by the NIMH in the 1990s that compared outcomes for people who took medications and those who did not. What they found is that those who did not take the drugs made changes in their life, including getting divorced, and ended at the end of six years with a better social standing than at the beginning. They weren’t frozen in place.

I think that goes to what you’re talking about. It can be a signal that maybe you need to make changes. But I agree, cultural conditions can be difficult to change, job and housing and all this. Going back to your original theme, Joanna, this is a picture of a philosophy of humanity, what it means to be human and so it goes back to your philosophical roots as well.

Moncrieff: On that point, I thought you put it really nicely at the beginning, Bob, that what it is to be human is a vast variety of reactions and patterns of behavior. Some people are more sensitive to bad circumstances than others. We’re not all the same, and some people will, through what’s happened to them in their childhood or through their genetics or biology, be more predisposed to react to things dramatically.

Some people do get really severely depressed, they take to bed stop eating and drinking and stop going out. Often, people will say to me, so surely that’s biological, and surely you’ve got to give them antidepressants. But I don’t think it’s any more biological than any of our other reactions. Of course, biology is involved in everything we do, but that doesn’t mean that that’s some specific process in our brains that’s driving our feelings or behavior.

As you point out, depression is almost always a temporary state, so those people who get into that really severe state do need looking after while they’re in that state, and do need support and care, but will come out of it. We don’t need to be zapping their brains with electricity or filling them full of antidepressants and goodness knows what else. We need to just be humanely looking after them and nurturing them until they find the strength themselves to get through it, which most people will.

Whitaker: The other thing in terms of a conception of what it means to be human is, I’m not the same person I was when I was 20 or 30. I was pretty anxious when I was 20-25 . As I grew older I became less anxious. I think, again, the conception with the disease model is this is who you are and always will be. That you’re like a fixed biological state, which, again, is not consistent with any sort of scientific understanding of how we evolve physically over time. This is an optimistic story. I think we need to emphasize that. What use then do antidepressants have? Do they have a place?

Moncrieff: I’m not sure that antidepressants have any use. I wouldn’t say that about all psychiatric drugs. I think antipsychotics have a place, for example, in the I think they can be helpful when someone’s acutely psychotic, just to suppress psychosis if it’s really uncontainable in other ways. But I’m not convinced that antidepressants are that useful.

If we think of antidepressants in a drug-centred way, that means trying to understand what sort of alterations they produce. Undoubtedly, one of the alterations they produce is to numb people’s emotions, so to reduce the intensity of negative emotions like depression and anxiety, but also the intensity of happiness, joy, excitement and positive emotions. That seems to go along with the sexual effects that they have as well, the reduced sexual sensitivity and libido.

In theory, antidepressants might be useful in reducing the intensity of depressive feelings if someone is really depressed. But the trouble is if you look at the research, I’m not sure that it actually confirms that they are useful. The differences between antidepressants and placebo are minuscule. They are not clinically significant and easily explained by other artifacts of the randomized trials. Such as the fact that people can detect whether they’re on the antidepressants or the placebo, at least in some trials, to some extent, and therefore they’re not fully double-blinded.

So I’m not sure that the evidence suggests that they have any use at all. However, there may be people who feel that something that makes them feel numb for a short period might be useful. I wouldn’t want to deprive people of trying them if they really want to, and if they really feel that might be useful.

What I would say to both prescribers and people who are thinking of taking psychiatric drugs is never take anything for longer than you really need to, because the longer you’re on something, the more your body will adapt. The more it’ll be difficult to come off, and the more harm will accumulate.

Whitaker: Just to conclude, your book is saying we’ve been doing things wrong. It’s been harmful. We need to rethink this whole thing. It’s not just about unmaking the myth. It’s about unmaking the way we take care of people. What’s been the response from the profession to this book, because it’s a big challenge to conventional treatments?

Moncrieff: I’m afraid it’s been entirely predictable. It’s been more of “But antidepressants work, and it doesn’t matter how they work, that’s all that matters. They work and they save lives”. Of course, there’s no evidence they save lives. So that’s been the response just to double down and defend the use of antidepressants, which doesn’t bode very well I’m afraid, does it?

Whitaker: I’m talking about the defenders of the faith, which mostly is coming from the profession. What is amazing to me is that they want to be people who practice evidence-based medicine, right? That’s one of the ways they promote themselves to the public. They say antidepressants work, but they can never point to research that shows they work beyond some minor thing over placebo in industry-funded trials. Which, as you say, even the meta-analyses show is not clinically significant. How do they get away with that in their own mind?

Moncrieff: I think there’s an awful lot of cognitive dissonance going on, but I think one of the problems is there is just so much research and people are easily swayed by big numbers. If you say we’ve got thousands and thousands of patients who’ve taken antidepressants and we’ve got a P value of less than .001, people will be enormously impressed.

I’m afraid that includes doctors who should know better and should have much better training in critical appraisal and statistical interpretation. People see what they want to see in scientific research, don’t they? If you want to believe that something’s effective, you’ll be able to interpret the research in a way that you want to very often.

Whitaker: Last question, you personally, together with the Critical Psychiatry Network, have had a profound impact on the narrative that is out there for the public. There’s a conventional narrative, but there’s a pretty strong counter-narrative that grows and grows. You certainly have been at the center of creating that counter-narrative. What is your thought for the future? Is that disease model narrative going to sustain itself, or is it going to finally collapse and we’ll get a paradigm shift? What’s your crystal ball telling you?

Moncrieff: My crystal ball tells me that it’s not going to disintegrate anytime soon because it’s so useful to so many people with power. But I think it is creaking at the seams now. I think it’s more fragile than it was, and I’m pleased to have contributed to that process. But I think the main credit needs to go to the survivor movement facilitated by the Internet, which can now bring people together so that they can finally be heard and find each other.

Whitaker: There’s something about personal stories also, when they connect they have a power beyond any sort of P values. Joanna, thank you so much for your time. It’s been a real pleasure speaking with you, and I know our listeners are going to be eager to hear from you.

Moncrieff: It was a pleasure Bob, really nice. Thanks.

**

Thanks for a great discussion, Bob and Joanna. Keep talking and writing—you are helping lots of folks.

Report comment

The age effect noted in the transcript is widely underappreciated. … I was pretty anxious when I was 20-25, but I am less anxious now. … . The global DALYS (Global Burden of Disease 2010) by age for some of the major mental disorders are: Depression– topping out at ages 20-25 with 7 million, declines to 2 million by ages 60-64; Anxiety tops out at ages 20-24 at 3 million, declines to 1 million by ages 60-64, etc.. Every psychological disorder is similar. All these mental disorders top out at least by ages 30-40. Age by itself appears to have population scale effects on the rate of mental disorders.

Why is that? Why does life stage have such a powerful effect? How might people take advantage of this effect earlier in their life? Why could not 20-24 year olds have the anxiety or depression levels of 60-64 year olds if they applied whatever secret is involved? They could. The answer seems to be that one simply learns through experience what triggers you and then avoid those triggers.

That has played out in my own life experience very powerfully. Earlier in my life, I went to the hospital for a mild case of food poisoning. A doctor measured my blood pressure — it read out on the top line as 160. This was considered a medical emergency they wanted to start me on an IV stat — I waved them off, I explained that for me this was normal; sitting in the ER waiting room would trigger a panic like response — when I escaped from that environment it would disappear. They did not believe me. I told them to fix the food poisoning, the severe hypertension would take care of itself stat after I left the hospital. It did.

I was in similar environments to the ER for many years (for example, school environments) that triggered equally extreme responses. As a teenager, in order to cope with these hyper-responses I was on a whole poly-pharmacy trying to address each symptom in turn. Once I was able to take control of my environment (for example, by learning online), my physiological and psychological hyper-responses stopped immediately. I stopped all my medical treatments and have never needed them again. I did in fact, achieve the effect I speculated on above — I figured out the trigger avoiding trick and I shifted my peak mental distress years into my early 20s and not my early 30s.

Merely, avoiding the anxiety/and other triggers, stopped the problem— cold. If I wanted to I could step outside of safe environment right now and my blood pressure would rapidly spike. Instead I am now comfortably resting at 115. I regulate my physiological responses by controlling my triggers.

I suspect it would not be that difficult to repeat this parlor trick with many many others who have entered a remission state through a similar process. The cure for me has been a simple change in environment. You say potato I say potaato. If you allow people (especially young people to choose the environment that is right for them), then their mental disorders might also disappear.

This is made all the more powerful when you add in polygenics. You then are not merely guessing who might be at risk — you would know prospectively. For me I am at the 90th percentile polygenic risk for anxiety, the 95th for PTSD, and the 95th for schizophrenia. These scores correspond very well to my life experience. At some point in my life all of these genetic risks were clinically active. However, as soon as I chose environments that did not trigger me all of these conditions immediately resolved. I suspect if I were to go out into the world and found my genetic doppelganger who had not learned the trick, then life would not be as great as mine as turned out. The people who clue in to the trick blend into normal and go unrecognized — those who do not learn the trick are tormented with severe medical and mental health challenges. The community then adds in all sorts of mental triggers that amplify the distress that those with mental disorders have. Mental hospitals themselves would have a similar triggering effect for many — the entire design concept of aggressive sociality would induce panic for those of some genotypes.

For me the bottom line message that I would tell a younger version of myself would be to avoid the struggles that I went through by simply getting a full genome sequence as early in life as possible and run comprehensive polygenic scores. You would then know exactly what your genetic risks were and could potentially (though perhaps not always) develop strategies to avoid the problems written into your genes.

If a school were not to accept my unique genetics as reason for accommodation, then I would request a legally authorized letter from them stating they would take full civil responsibility for the inevitable medical crises that would ensue. As it was my school system merely watched many children similar to me without in any way responding to the crisis that we were in and apparently this problem has only intensified in recent years.

The cure for me once I understand the logic was quite straight forward.

My comments above might be a highly fruitful direction for the anti-psychiatry movement to take. Even in my experience, there might have been a certain rationality in taking the multiple pharmaceuticals I needed to make it through my teenage days. However, as shown above the even more powerful therapeutic approach is to simply stop the physiological responses by avoiding the triggers.

Report comment

We have answers for that. During adolescence, that ends around 21, your brain creates new pathways and the pathways that are less used go through a process called pruning. 20s we really don’t see an increase in depression (middle age men have a high rate of depression.) But it is when we see bipolar disorder and schizophrenia spectrum disorders start.

Report comment

That’s not really an answer, though, not scientifically. It’s a hypothesis, untested and unproven. In fact, the very idea that cases of “schizophrenia spectrum disorders” or “major depression” or any DSM diagnostic category have common etiologies is pure speculation. It is just as legitimate to hypothesize that environmental triggers play a role in all forms of “mental illness”. In other words, the same etiology might result in PTSD, ADHD, depression, anxiety or psychosis depending on the person and the context. At this point, there is no scientific basis to assume the DSM categories are legitimate in any scientific sense, so talking about etiologies of these so-called “disorders” makes no scientific sense at all.

It is worth noting that a two people could have literally no symptoms in common and yet qualify for the same “diagnosis.” Plain common sense says that can’t be right.

Report comment

“It is worth noting that a two people could have literally no symptoms in common and yet qualify for the same “diagnosis.” Plain common sense says that can’t be right.” Steve, can you give an example of this — two people having no symptoms in common but yet qualifying for the same “diagnosis”?

Report comment

I have found four out of five different for MDD and ADHD.

For schizophrenia, we need two out of the following 5 symptoms for a mere one month.

Delusions

Hallucinations

Disorganized speech (e.g., frequent derailment or incoherence)

Grossly disorganized or catatonic behavior

Negative symptoms (i.e., diminished emotional expression or avolition)

We need one of the first three. So we can have hallucinations, disorganized speech, and grossly disorganized behavior. Or we can have delusions, catatonic behavior, and negative symptoms. Nothing in common between the two.

For Bipolar I disorder, we need four of the below criteria:

Inflated self-esteem or grandiosity

Decreased need for sleep (e.g., feels rested after only 3 hours of sleep)

More talkative than usual or pressure to keep talking

Flight of ideas or subjective experience that thoughts are racing

Distractibility (i.e., attention too easily drawn to unimportant or irrelevant

external stimuli), as reported or observed

Increase in goal-directed activity (either socially, at work or school, or sexually)

or

psychomotor agitation (i.e., purposeless, non-goal-directed activity)

Excessive involvement in activities that have a high potential for painful

consequences (e.g., engaging in unrestrained buying sprees, sexual indiscretions,

or foolish business investments)

There are obviously many combinations of the above that would enable two people with no symptoms in common to fit the criteria.

I could go on.

Report comment

Thank you Steve for your response. I got it. For schizophrenia, “So we can have hallucinations, disorganized speech, and grossly disorganized behavior. Or we can have delusions, catatonic behavior, and negative symptoms. Nothing in common between the two.” I guess the DSM wants to cast as wide a net as possible based on their professional members’ subjective clinical observations.

Report comment

It’s all basically “Behavior that makes adults uncomfortable.” That should be the only “diagnosis” in my mind!

Report comment

Thank you again Steve!

“It’s all basically “Behavior that makes adults uncomfortable.” That should be the only “diagnosis” in my mind!”

For children, the “adults” are school teachers and parents. For individual adults ending up being psychiatric patients, the “adults” are their family members, community members, people at work who align with psychiatry.

Report comment

Yes, I largely agree. DSM does not instill much confidence. Nevertheless, one must acknowledge that DSM has been applied to work backwards from GWAS to clinical diagnosis and this has resulted in valid genome wide significant SNPS. That is they used DSM criteria in large samples of schizophrenics etc. — some upwards of 1 million people — they then found SNPs from these studies and constructed polygenic scores.

Thus, while at the clinical level DSM can be quite inaccurate, when it was applied to large samples in GWAS, more accurate clinical appraisals can be made.

This means that DSM is picking up on the signal! DSM is scientifically anchored in the disease constructs, while at the individual level diagnosis has been difficult when only observing behavioral phenotypes. If they can predict DSM diagnosed schizophrenia simply by calculating a polygenic score, then this means that the DSM is finding the genetic signal. If the DSM were purely nonsense, then you would only have GIGO. But we know that the risk of conversion to clinical schizophrenia exponentially increases with polygenic score. Given that ~1% of the population is schizophrenic and I am at the top 5th percentile of risk my risk of developing clinical chronic schizophrenia is actually probably fairly low – perhaps 10%. None of my other family members have been diagnosed. For me it is more of a shadow type syndrome — I have had very very minimal delusionality in my life and no hallucinations.

The polygenic score was how I found that I have highish schizophrenia risk {95th percentile}. This for me has been of pivotal importance. If you just give a clinician the DSM-5 and tell them to give us a valid diagnosis, then you might as well just throw a dart at the wall. My doctor was just not in the right ballpark – it was almost worse than a guess. With my deep knowledge of my family’s behavior, I knew right away that schizophrenia was the right choice.

With large large sample sizes all of the tiny effects added up and an unbiased answer could be found. This a remarkably powerful 21st Century medical advance. When I hear online of those on social media talking about their psychiatric diagnoses I am fairly confident that their diagnosis does not in any way align with reality. Simply looking at phenotype with a checklist is a hopelessly primitive idea.

Almost all of my other family members are on the schizoid spectrum, though at a subclinical level. I am also on the schizoid spectrum, and have largely remained subclinical. Understanding what schizoid spectrum actually means and how this would affect how my family members would interact with me has been a game changer. Something clearly was odd with my family, though I was never able to quite figure out what that was — until I go the genome scan. Once the genetics was revealed to me it was like a curtain dropping and it allowed me to understand what was happening and to protect myself from their EE, conversational deviance, bad advice, etc..

Report comment

We will have to agree to disagree on this one. The massive numbers of genes needed to predict a tiny percentage of the possible “schizophrenia” cases does not make for accurate “diagnosis”. The number of “schizophrenics” who do NOT have these high-risk combinations is in itself sufficient to invalidate this approach. Not that a small percentage of folks (like yourself) may be able to find some correlations – it is certainly more than possible that a certain subset of “schizophrenia” gene combinations conveys a certain vulnerability to psychosis. However, correlations with trauma, urbanization, and other social causes are much, much higher than anything these giant genetic experiments have ever demonstrated. At best, a certain level of vulnerability can perhaps be imputed from this data, but to suggest it is CAUSATIVE of “schizophrenia” is just not the case.

Report comment

Polygene, I respect your right to post your comment above. And you have a right to your opinions. But you do NOT have a right to fabricate either FACTS, or REALITY. And, your reality is ONLY YOUR “reality”. You claim that you are “on the schizoid spectrum”. I say that has no solid connection to objective, consensus reality. It’s only “real”, FOR YOU, simply because YOU BELIEVE it to be so. In other words, your “schizoid spectrum” is only as real as presents from Santa Claus. You must live in a house with a large, inviting chimney….

My lived experience has been VERY DIFFERENT from yours.

This is the TRUTH of MY REALITY:______

“Psychiatry is a fraudulent pseudoscience, a drug racket, and a social control mechanism. It’s 21st Century Phrenology, with potent neurotoxins. Psychiatry has done, and continues to do, FAR MORE HARM than good. The DSM is in fact a catalog of billing codes. EVERYTHING in it was either invented or created, nothing in it was discovered.”

In plain English, the DSM is organized MEDICAL FRAUD for profit. Your “schizoid spectrum” only exists in YOUR MIND….

Please, RSVP and try to disprove my claims….

Report comment

One of the large errors with the DSM is that they take some behavioral sample and then create an eternal diagnosis that somehow speaks to the very core of your being. This can be highly misleading.

So for me, my actual diagnosis was Bipolar I. There was no clinical sign of schizophrenia even when highly agitated — the bipolar 1 diagnosis does follow the logic of DSM. However, no one in my family is on the bipolar spectrum –not even close. The family just nodded politely when given my diagnosis without any realization that with the very high heritability of bipolar 1 they would also be expected to carry high genetic risk and probably would also have at least some observable bipolar 1 traits – they do not. My polygenic score for bipolar 1 came back so average I did not even bother recording it.

However, in terms of DSM I checked almost every SINGLE diagnostic box for Bipolar 1. It was a perfectly valid DSM diagnosis by a highly trained clinician. Yet, it was simply incorrect. Aside from 2 months in my life, I have never exhibited this behavior. DSM created a permanent diagnostic label for something that I only exhibited temporarily and under highly abnormal conditions. Supposedly I would need to be treated for life for this.

How did my symptoms emerge? Under what specific context? I had not slept in about a week during a prolonged summer heatwave — we do not have air conditioning. For me, air conditioning has had curative effects for my problems.

Report comment

You are making my point for me. There is no way that any “genetic risk factors” can possibly explain more than the tiniest percentage of “bipolar diagnoses.” There is no effort to establish any other cause, including the obvious one of lack of sleep. They just see if you “fit the criteria” and label you with these subjective “diagnoses” that have no particular connection to reality. There is no “DSM logic”. It’s complete speculation.

Report comment

There is of course the example of the Genain Quadruplets. What is the probability that each of these 4 genetically identical sisters would develop schizophrenia? 1 in ~1 billion?

How will DSM in its next upgrade (DSM-6) include genetics? Bipolar I is highly heritable — it is a very genetic illness and it has 1% lifetime prevalence. The latest GWAS exceeded 150,000 patients. With only age+ gender+ polygenic score, area under curve begins to offer relevant information. Looking at especially the upper end of the risk distribution might then be important for identifying those at risk and creating prevention programs. We could start to see medical centers with very specialized prevention/treatment services for highly genetically characterized patients (instead of more tourist types like me who really are not true patients).

The argument that DSM diagnosis are empty could soon strongly be rebutted by irrefutable clinical evidence. If DSM moves towards genetic confirmation in the next edition, it could start a revolution in psychiatry! There would be much more exact diagnostic labeling that perhaps combined phenotype and genotype.

Even now I doubt whether I would make the grade for bipolar I. I suspect that with current genetic technology, looking at my full genome along with that of other family members the answer would be all too obvious — what is opaque by only considering presented phenotype would be crystal clear when adding polygenics.

I realize that I have been highly internally inconsistent with my comments — I am still figuring things out. What I see now is that bipolar 1 was in fact, the “correct” diagnosis for me purely on a behaviorist level. Did I exhibit all of the symptoms checked off? Absolutely. However, I also can see the flaw in this thinking. This diagnosis is not anchored in a plausible etiology (genetic or otherwise) and is then not anchored in a treatment or prognosis. It is hollow. Many many millions of people could take a fairly inexpensive full genome test for ~$200 and find their diagnosis was likewise hollow. Millions of people would suddenly realize that they received dangerous psychotropic medicines for no justifiable reason clearly would not be a good look.

Genetics is a major leap in medical science! Up till now it has never been obvious what exactly others were referring to when they had their lived experiences. Lived experience of what exactly? Polygenics allows us to more precisely define the boundaries of this lived experience and move it outside of a subjective inner dialogue that is not easy to translate to others. It also allows us to calibrate our own personal experiences to “normal” and see whether labels of “abnormal” truly apply to us.

While polygenics might be somewhat immature yet, it could still indicate that the future direction. It would immediately harden up the scientific credibility of DSM. Once the phase transition happens at perhaps patient sizes of 1 million in the GWAS, the entire genetic architectures of bipolar, schizophrenia, ADHD, etc. would fully unlock and that would be monumental. So, it is critically important to get on the right side of this wave before it makes landfall.

Report comment

You are incredibly overly optimistic based on the evidence to date. Normal science postulates a cause and tests for it. Psychiatry postulates a conclusion and looks for data to “prove” it after the fact. If there are some genetically-identifiable cases, they ought to be identified as SEPARATE CONDITIONS that may be amenable to treatment. But the vast majority of DSM cases have NOTHING in common with the genetics you mention. NOTHING.

I would also ask you to consider the following: even if genetic markers DO occur in common between people with these subjective “disorders” tossed on them, why does that mean these people are “abnormal?” Maybe it’s just NORMAL to have people with a wide range of activity levels or sociability or any of a number of these “criteria” which remain completely subjective and unmeasurable scientifically? For instance, why is there no “Hypoactivity disorder”? Is this because there are not kids who have very low activity levels? Or perhaps it’s only because kids with HIGH activity levels ANNOY ADULTS, even if their behavior is entirely normal? Maybe there are advantages to a certain genetic arrangement which are ignored by your normal/abnormal framing?

GWAS is a dead end. At best, it will identify a tiny, tiny percentage of vulnerable people, and we already know that many such people never develop any kind of “DSM” problems. And the vast majority so labeled have zero connection to the GWAS genes in question.

The problem is having the cart before the horse. We can’t decide to define diagnoses by totally subjective criteria and then expect scientific verification of them. We have to do it the other way around, and again, it will only be a tiny percentage that are predicted by GWAS data. Trauma and loss is a much better predictor BY FAR of the presence of “mental illnesses.”

Report comment

I’m calling you out, Polygene. Please describe the genetic mechanism of action by which (supposedly) so-called “bi-polar” is “inherited”? How do you distinguish between a psycho-social, and a (supposed) genetic cause for so-called “bipolar”?….

So-called “bi-polar” is no more “real” than presents from Santa Claus.

And no more “real” than any other invented, created, BOGUS DSM “diagnosis”….

Report comment

Eureka! I finally have it!

Time to call in the economists!

You know that this is getting serious when you call in the dismal scientists.

They can tell you the answer — it is just you are not going to like it.

Abnormal psychology is not a problem of psychology, but of economics.

Steve, thank you for your comment, it has finally helped me to piece things together. Up until now, I have not been that sure exactly what happened with me. However, now this feels like it quite close to the truth.

Primary school went so great for me. It was such a fantastic time with a stay at home mom and all the activities from school and being part of the community. Yet, in just a few short years things would crash down for me. What happened?

Almost, from the first day of kindergarten, some of the kids arrived in class with a range of emotional problems. Their parents were getting divorce, … and the whole range of modern urban social problems. Our family was perhaps the most highly functioning in town and my parents were highly trained in all of the latest psychological theory. We were this beacon of hope for our community — almost a model family. Hmm, sounds good: What happened?

After primary school it was time to make money and for my mom to go out there and start making money. Basically, start working around the clock. Money all the time. Money, money — all the time money. Our well-being then had a multi-year decline. We were no longer the model family. We were no longer being a positive for others. We were already displaying “negative” symptoms — that is in the mental well-being economy we were no longer freely giving positive energy.

What was the motivating factor for this change besides the money? One thing that was quite noticeable is that when you are the model family, then everyone starts dumping their problems on you. It allows other people to dump more of their emotional problems of their children on you because you are doing so well. You are the golden goose and you are laying golden eggs that others can freely take from you.

This is a classic problem from economics economics called the tragedy of the commons. You have some shared resource say a nice pristine lake. You have no restrictions on how people can use the lake — so some people start dumping toxic waste into the lake — the good people clean up the pollution and this only encourages the others to pollute more. They can freely externalize their negatives and they are financially rewarded for doing so.

This is the problem that we faced in the school system. Parents could work to excess — they maximize their personal utility, while the children are put into worse and worse mental states. The utility of the children is ignored and once they have left the home the wealth stays with the parents. Children then are taking all of these psychotropic medications, they are having all of these side effects such as weight gain etc., and school has now become this truly disturbing dystopia in which most of the school is now chronically needing help from others. These are no longer precious school days to be remembered for a lifetime, but more days to be sped through as fast as possible and forgotten.

What does that suggest would be the arc for childhood well-being? There is almost no bottom to the down drift in the dumping that could occur. The lives of children could simply decline endlessly — and it largely has. Yet, the youth mental health crisis now appears to have almost reached some near theoretical minimum. As a response, to such dismal childhoods there could be a fertility implosion; this has happened. Also people could demand school choice — this is also happening. Something had to change — and it did. With school choice you can stop the race for the bottom by allowing children a realistic exit option when others play the negative externalities card. If given a way out of the toxic school environment that now exists, then things could rapidly improve. When I played the school choice card I instantly recovered from quite severe medical symptoms.

Why has this “dumping” strategy only emerged within the last few decades? What is so new about now? Modern urban cities. In a highly cohesive rural community this type of behavior is simply not allowed. Children are highly protected because they truly are the future of the community. If you do not stop this type of behavior your community can rapidly collapse. This is probably why our rural relatives were so surprised by our behavior. To them it seemed so irrational – were we not at all interested in what would happen even one generation forward? Not really. Playing negative externalities means you are playing the short game without any concern for the long term viability of your society. For us, the long term viability of our society is already highly in doubt — our society has rapidly and profoundly entered into demographic collapse: A truly dramatic decline in fertility rates is underway countered with an open borders policy that is further destabilizing our community. Reversing open borders will then merely lead to accelerated mid-term population implosion.

There it is. That is my best try yet. It is not that we did not know how to be mentally healthy — we did. It is more that we no longer wanted to be suckers. Optimizing personal mental health in that context is not rational. Knowing the path to mental wellness does not really help that much. So, for me, there is this consolation in realizing that my lived experience in some sense was actually utility maximizing — though just not for me. We were rational. You then feel sympathy for the unfortunates who did not figure this one out. Of course longer term, all that will remain of our community is a crater. Playing by these rules of logic does not offer that many wins.

It is like cell phones. Without social coordination, you can get stuck in a local minimum where everyone is worse off. Finally after decades it is realized that we can get out of our current youth mental health crisis by dismantling the monopoly public education system that has allowed lack of choice to result in the tragedy of the commons.

In this scenario, the mental health challenges of the children is more sociological/economic than it is psychological in origin. This is all quite a dismal assessment of what happened, though that does not in some way mean that it is not correct. In this instance we can see how your critique of mental illness is quite accurate — mental illness here was really not something existing so much in the mind but in the community and the incentive structures that existed.

Report comment

You speak wisdom. Our lives are all polluted by users who wish to profit from our hard work and our sufferings. We no longer have real communities in most cases. We are constantly working against forces that are not concerned with our welfare. It is exhausting and it breaks us down. SO much more going on than biology!

Report comment

Thank you for responding Franklsc!

Yes, that is a good point to refer to the continuing brain development. It was just that I was trying to align the discussion with my particular experience. For me, a fairly simple environmental change had an immediate and profound effect on my life. My brain did not somehow change over night when I switched to online learning, though my physiological response did!

It was the most powerful experience I have had in my life. I sat in front of my computer the first time I started on my online courses and I had an enormous feeling of relief. Relief because I noticed that I did not have a panic response in a learning environment. That had not been true for many years. Since then there has never been any of these panic responses that had been continuous in the bricks and mortar world. My ability to perform academically took off once I was away from the extreme stress responses I had in the physical world.

The Burden of Disease figure by age for mental illness seems to show that some part of the very large decreases in all mental illnesses is probably due to similar learning effects/environmental changes. In a psychological treatment environment it is likely well understood that patients will be stuck in a rut for as long as they remain in the same environment that they were in which caused their probelms. What is exciting with the online world is that someone could profoundly change their environment simply by going online — as I did. This opens the possibility of quite rapid social change [as we saw during COVID]. People can change their lifestyle overnight and then they can see what effect this might have. Many people saw an enhanced online life during COVID.

Interestingly, these declines for all of the illnesses occurred decades and decades after most of the brain changes have already been largely completed. So with schizophrenia, alcohol and drug abuse disorders, etc. you see ongoing declines for people into their 60s. By that time some of these illnesses have almost vanished. While there might be some survival effect involved, it is highly notable how large these age effects actually are.

Report comment

“The Burden of Disease figure by age for mental illness seems to show that some part of the very large decreases in all mental illnesses is probably due to similar learning effects/environmental changes.”

From what I’ve read, the Covid debacle has greatly increased, not decreased, the defamations of people with the “invalid” psych DSM diagnoses. Can you please give citations to how the Covid situation has decreased psych diagnoses, please, Polygene?

Report comment

Thank you for your question Someone Else!

The research I was thinking about in particular were studies that considered calendar year effects of schools. These studies have found the interesting result that school children apparently display self-harming behaviors etc. that sync with the school calendar. Other age groups do not show this pattern. However, during COVID this pattern of behavior disappeared. The unsettling possibility then is that it is the school system itself that is inducing mental health problems in children.

We also saw a very large decrease in youth drug and property crimes during COVID. While this might be explained away due to the economic and distribution effects due to the epidemic, what is of interest is that these effects have lingered. By definition such crime declines would result in greatly reduced conduct disorder diagnoses under DSM. It seems as if COVID has reset something in the school environment and this has had lasting effects. There perhaps was an institutional pathology present in the school system which COVID has somehow disrupted.

To access the specific studies alluded to above simply chat with an LLM and it will help direct you in the right direction.

In terms of your observation of evidence pointing to greatly increased psych diagnoses during COVID, I would refer back to the idea that generalities do not help to uncover the more individual granular truth. Deaggregating and looking more at the individual level can then reveal personal lived truth. For the more socially inclined people, COVID clearly would have been a tremendous stressor. That would seem to be reflected in some of your data points. Yet, for those who lean in the more non-social inclination, COVID would seem to have been a tremendous anti-stressor. So, instead of trying to create some sweeping universal conclusion about mental health during COVID, thinking more at the level of personal gentoypes would be very helpful.

Being fully genome aware, it was not difficult for me to accurately predict that I would do very well during COVID type events — and I did. The COVID social restrictions created an environment that I thrived in. Interestingly, many other people noticed how much better virtual type lives worked for them. Some organizations had almost 100% of their workers vote for continued online work. It was then that organizations starting creating mandated return to office policies. This was such an obvious example where mental health was placed second to organizational motivations.

Much of the youth mental health “epidemic” can then be recognized as an environmental effect. Putting children into highly rigid monopolistic school systems might be a central driver of the emergence of very unhappy and often labeled as “mentally ill” children. It is a double whammy for these children to then be sent into a highly rigid and questionable psychiatric care environment.

Highly rigid and pathological government school and medical systems were at the center of my own personal problems. Government is in the unique position to create entirely maladaptive social structures that are not suitable for a large fraction of those it serves. It then creates deeply pathological institutional structures that often make people very medically and mentally unwell. Without any competitive forces it is not obvious that there is any other choice but to have dramatic levels of childhood psychopathology. Until you age out of the system you are trapped in a high pathogenic environment. They have normalized childhood mental illness and after a while no one is able to see the obvious absurdity. At the same time, it is typically never even imagined that they could be held criminally or civilly responsible for their behavior, while private corporations are exposed to such enforced responsibilities for similar behaviors.

As soon as I escaped the bricks and mortar school system and went to online learning I immediately felt overwhelmingly better which then allowed me to also escape the medical system. Escaping monopoly organizational “illness” is then a powerful way to escape personal mental illness. The wave of school choice that we are now witnessing could lead to a profoundly improved era of childhood well-being. As soon as children are given escape options to improve their mental well-being, they will take them.

Report comment

[Note: For some reason the reply button to your comment and a few others mysteriously has vanished. So I will reply to you instead from one of my previous comments.]

Bill, thank you very much for replying to my comment. I am sure you understand how very important it is for people like me in the community to talk about their experiences and it is always such a pleasure for me to have an opportunity to add more layers to the conversation.

Being listened to is so empowering. I can fully understand that most people really do not want to hear about other people’s problems — I suspect that many people already have more than enough of their own problems, though I have thought a lot about my experiences and I think that I can help others who might be in the same boat that I was in.

Surprisingly, I have until now rarely mentioned what happened to me. To an almost complete extent — I just got on with my life. For me mental illness is not some sort of organizing principle or something that I want to go on a great mission for — It is more that I hope that my insights can help others who might be struggling; provide some ideas that can change their life — I have done everything possible to make it a footnote in my life.

However, my impression is that there is so much left out of the discussion that is not being said by the treatment community, the anti-psychiatry movement, policy makers, or even the patient community …. . There is this gap in perception, in understanding the totality of the reality — it is the core strength of the schizoid perspective to want to seek out such mysteries — reality itself needs to be struggled with to find higher levels of truth. To get all of what I have seen in my trip to a faraway land out there I would need to write probably a multi-volume magnum opus.

I have only disclosed about a tenth of the genetics that are at play with me. Even on the genetic side there are large gaps that I have avoided filling in. I could also fill in the gap related to the economic utility of insanity from the view of the tragedy of the commons — the idea that madness can be utility maximizing. The rural urban perspective is also highly relevant. Our rural relatives simply cannot believe how we have lived — if we had exhibited our city type behavior back in our family’s heart land, then they would have simply never allowed it — in the big city, our maladaptive type behavior will often get you a medal. etc. etc. … There is just so much to talk about and I do not want to bore people excessively.