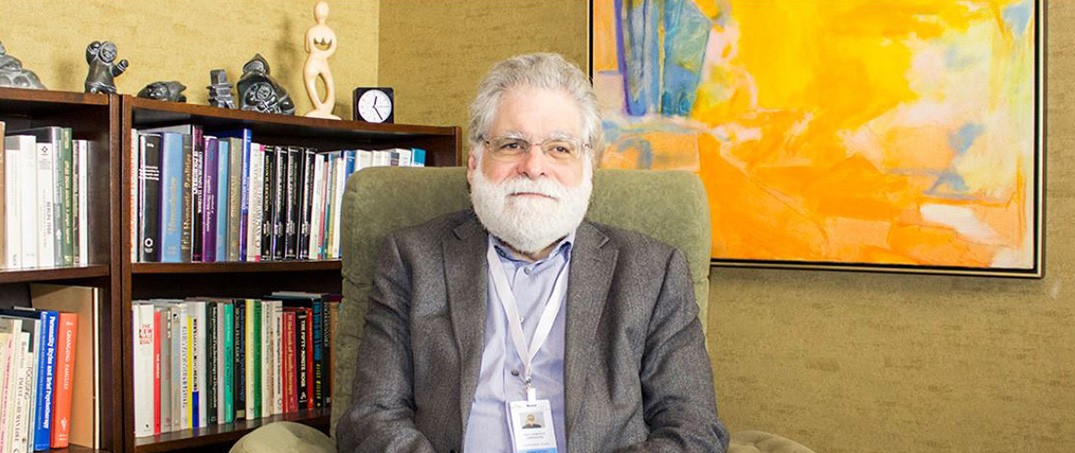

Laurence Kirmayer is one of the most influential figures in cultural psychiatry today. A psychiatrist, researcher, and theorist, he serves as James McGill Professor and Director of the Division of Social and Transcultural Psychiatry at McGill University and Editor-in-Chief Emeritus of Transcultural Psychiatry. Across decades of work bridging anthropology, psychiatry, and cognitive science, Kirmayer has advanced a complex view of mental health as inseparable from culture, history, language, and political power.

His research ranges from Indigenous youth resilience and narrative medicine to the diagnostic metaphors—such as “chemical imbalance” or “trauma”—that reshape identity and possibility. He has helped pioneer integrative approaches that unite phenomenology and neuroscience, including a biopsychosocial model grounded in enactive and embodied cognition, as well as a person-centered, ecosocial framework for understanding suffering beyond reductive biological paradigms. His critiques extend to how psychiatric categories reflect colonial histories and obscure social causes, as well as how attempts to localize mental health interventions may still impose Western norms.

Kirmayer’s scholarship on narrative, metaphor, and cultural psychiatry aligns with ongoing efforts by Indigenous psychologists and anthropologists to reframe trauma and healing through culturally grounded practices, as reflected in recent collaborative work calling for a decolonial turn in psychology. Drawing on 4E cognitive science, he proposes that metaphors are not simply rhetorical tools but embodied and enacted processes embedded in local social worlds. These shape how people experience distress and how clinicians make sense of it.

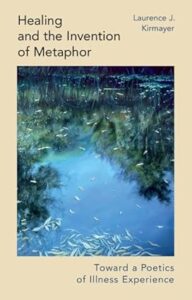

His forthcoming book, Healing and the Invention of Metaphor: Toward a Poetics of Illness Experience (Cambridge University Press, July 2025), extends these themes by exploring how metaphor, narrative, and imagination shape suffering and healing across cultures, while offering a critical account of the symbolic and political frameworks embedded in contemporary psychiatric and biomedical practice.

In this wide-ranging conversation, Kirmayer explores the politics of diagnostic language, the structural roots of suffering, and the poetic potential of metaphor to disrupt conformity and open new avenues for healing. From the medicalization of culturally normative expressions of distress to the reification of trauma, Kirmayer shows how dominant frameworks can limit imagination, flatten complexity, and displace political realities with individualized solutions. He calls for a psychiatry that listens not only to symptoms but to the metaphors and metaphysics that animate people’s lives.

The transcript below has been edited for length and clarity.

Ayurdhi Dhar: Much of your writing is about the role of culture. Many people believe we can understand individuals in isolation, or that culture can be studied as an afterthought, people without context. You’ve written that we are fundamentally cultural beings. Could you explain?

Laurence Kirmayer: We tend to assume that the ways psychology and psychiatry look at people are universally applicable. But these ways of seeing have a particular history—one that’s deeply shaped by culture.

Today, especially in psychiatry, there’s a strong tendency to frame mental health problems in biological terms—neurobiology in particular—and to treat that framing as automatically universal. While there’s certainly some truth to those biological explanations, the fact remains that human beings are fundamentally cultural. We’re born in a highly immature and vulnerable state, with brains that are plastic, ready to be shaped, molded, and programmed with cultural knowledge. That’s how we adapt.

We don’t have the sharpest claws, the longest teeth, or the warmest fur—yet we’ve populated the entire world, thriving in a wide range of ecological niches. We’ve created many kinds of societies, families, and communities, and we’ve done that through shared learning and cooperative activity. This high level of cooperation and creativity—our ability to build diverse environments, homes, and relationships—is possible because of the human brain. In a sense, you could say the human brain is the organ of culture.

Most of what we do depends on our more complex mental faculties, and those faculties are, at their core, social. That’s what it means to be a cultural being—not the way “culture” is often used in psychology, as if it’s something only “other” people have. There’s this idea: “We just do things the way they are—we’re just people—but those people over there, they’re a little bit different, a little bit weird, and they have culture.”

But the truth is, as soon as you learn how to be physically present with others, how to relate with synchrony and resonance, you’re already becoming a cultural being.

Ayurdhi Dhar: Tell us, why the interest in studying cultures? Was it academic or personal?

Kirmayer: It is a mix. It was a personal thing, a sociopolitical thing, and an academic thing.

Personally, I come from a family of second-generation immigrants. My grandparents came from Ukraine and what is now Romania. They arrived as poor, working-class Jews who were living in an environment where there were frequent pogroms and violent anti-Semitic attacks. They were fleeing that difficult situation, and they found a place in Canada.

I grew up in a context where there was a recognition of that story. Canada is unusual in some ways because of its high level of diversity, including English and French settler societies, and, more recently, because of a serious acknowledgment of Indigenous peoples. I grew up with a political ideology of multiculturalism, which says we should acknowledge diversity. Canada has embraced this diversity in explicit political terms. I grew up with that personal story and in a political environment where there was a celebration of difference.

I trained initially in psychology, and then I went to medical school. I met medical anthropologists who taught about the diversity of healing systems and perspectives around the world, which for me was utterly fascinating. When we talk about culture, we are talking about all the taken-for-granted background information, ways of life, implicit values, and things we’ve learned to do automatically that make us feel comfortable and able to do what we want to do. All of that is part of the fabric of culture.

Ayurdhi Dhar: That brings us to this point that culture is fundamental to what is considered psychopathology, what we consider disorder. Could you give some examples of different ways across the world of looking at human distress—what people consider distressing, and how they understand it and make meaning?

Kirmayer: You use the term “psychopathology,” which implies there’s some problem in the psyche. “Psyche” is a word that comes to us from Greek, and it means something interior. It means mind. It’s not a word that exists in the same way in every culture.

When we talk about cultural differences, we’re going to find both similarities and differences, because we’re made up of similar stuff and we have certain existential universals. We’re all born in a vulnerable state. We grow and change dramatically. Eventually, we get sick, suffer, and die. These are like the Buddhist noble truths. They depend on our biology, but also on the nature of human experience, and they get rediscovered, reinvented, and reshaped in every cultural tradition.

The fact that we have “psychopathology” per se, and that we have Psy-disciplines like Psychology and Psychiatry, is the consequence of a particular history—a particular way knowledge has been divided up and institutionalized in terms of professions, structures of healthcare, and so on. It’s not the same everywhere else. Things don’t get divided up. Even though human experience has many of the same facets, they don’t get lumped together in quite the same way.

I was trained as a psychiatrist working in a general hospital, and I was the consultant to the dialysis unit in our hospital. People were often very defensive. They said, “I don’t need to see a psychiatrist. I have a serious physical problem. I have no mental health problems.”

This brings us back to the idea of diagnoses. What are we labeling when we say, “This person has a depression”? Some of those people I saw on dialysis and in primary care would fit the criteria of DSM-3, 4, 5, and ICD, and all these other systems. Some of those people would have symptoms that fit quite well. The practical question you’re raising is: how well does that work?

There was literature from anthropology—and this speaks to your question about culture—an important paper in the late 1970s by Arthur Kleinman, looking at depression in Taiwan and in North America. He described how people there, who had some of the same symptoms as depression, were not focusing on those symptoms. They were focusing on physical symptoms. This got called somatization because the assumption was that depression is a mental disorder, a psychological condition, an emotional problem, and that you should be talking about your emotions—that you feel sad—and that’s how you should frame it.

But when he looked at people in China, their problems involved feeling irritable, fatigue, pain, heaviness—a lot of physical symptoms. This got written about as somatization. But in the hospital, I was seeing people who were not coming to psychiatry, but to primary care or nephrology, and when they had some symptoms of depression, the main way they expressed them was through physical symptoms. They were not coming and saying, “Doctor, I think I’m depressed.” They were coming and saying, “I’m exhausted and tired all the time. I can’t do anything. Help me.”

This, for me, is very important because there was this idea that Asians somatize, Africans somatize, everybody except Westerners somatize. Then, lo and behold, when you go to primary care, North Americans somatize. The lesson there, partly, was that the norm around the world is to express suffering as physical symptoms.

Ayurdhi Dhar: You’ve written that there is a bias against somatization. Psy-disciplines often advocate that if you emotionally express and process, or if you psychologically figure something out, it is somehow truer, more authentic, or superior to having an experience in your body. Do you think this bias in psychiatry and psychology had something to do with the fact that we completely ignored that people in our own culture also show bodily signs?

Kirmayer: There’s a symmetry between the biomedical physician who is just looking for something in the body and ignores how people are feeling, and the very psychologically oriented practitioner who is focused on how you’re feeling and ignores what’s going on in the body.

Horacio Fabrega, years ago, looked at people on a psychiatric ward and asked them about physical symptoms. They all had many physical symptoms, but nobody was talking to them about it, because it was like, “Okay, you don’t have a serious medical illness, so it’s not interesting to us that you’re actually feeling bad.” There is a bias built into how we’ve cleaved things apart.

This is sometimes portrayed as mind-body dualism. But it’s really a consequence of professionalization. Some theories justify the idea that the real action is in psychology, and everything else is not important. Or, in mainstream psychiatry in North America today, it’s the opposite claim: that it’s all really about the brain, and consciousness and awareness are just epiphenomena.

Human suffering has many different dimensions. We’re talking about body and mind, but there are also social dimensions, spiritual dimensions, relational dimensions. As practitioners trying to help someone, we often want to simplify and focus only on psychology or the brain, but we need to be honest and recognize that this is only one facet. We’re coming at it that way because those are the tools we have, that’s how we were trained, but that approach is like looking through a keyhole at something more complex.

About depression cross-culturally, one can say that there’s a state you can get into—a brain state, perhaps to some degree—where you don’t respond well to ordinary social input and reinforcers, and you’re stuck. One can say there’s a psychological state in which you’re full of pessimistic and self-deprecatory thoughts, and they’re just looping around, grinding you down. But there’s also a social position you occupy that is preventing you from getting out of that, or a spiritual position where you’re viewing life as not making sense and you’ve lost sight of a bigger picture. If we think in that multidimensional way, then we can have multidimensional assessment and multidimensional interventions that we can try to guide people toward.

Ayurdhi Dhar: A couple of years ago, I went to a psychiatric conference. It had people from all over the world, and it was about social psychiatry. Some public sector Indian psychiatrists even impressed me with how sensitive they were, and how openly they challenged the objectivity of diagnoses. They talked about poverty, oppression, marginalization, and gender violence as causes of mental health issues.

But even then, when I asked them a simple question—“What do you do then? How do you fix it?”—The first answer I got was antidepressants. The second response I got was, “It’s complicated,” which I remember Arthur Kleinman writing is a ridiculous cop-out.

I ask you, what can we do then as Psy disciplines? We have acknowledged that inequality plays a huge role in human distress, but we immediately go back to individual solutions. This is connected with what you wrote, which is that psychiatric concepts and categories “bear the traces of their colonial origins and reflect current structural inequities maintained by constructs of race and ethnicity.” If this is true, then I don’t know if we can use these same concepts to fix the structural determinants causing these mental disorders.

Kirmayer: There’s a famous quote from Audre Lorde about how the master’s tools will not dismantle the master’s house. You framed it in a very important way, in terms of the history and the enduring structures. We’re supposedly in a post-colonial era, but really, there are new structures of domination.

One thing that helps is that when people are in a predicament, they should not totally personalize it. This is the core of narrative therapy, as proposed by Michael White and David Epston, in which you’re looking not just at the person’s story, which is very important: “How do they understand their situation? How do they understand the trajectory of their life or the nature of the world they’re in right now?” But you’re also helping to reveal the larger narratives that we’re all embedded in. You’re helping the person not to blame themselves, to understand better what they’re up against. Their example was around eating disorders, and how ideas of what a woman’s body should look like circulate in mass media and have powerful impacts on people.

While working with people, bringing in that element is helpful in terms of helping them understand, “Okay, this is what I’m negotiating with. It’s not just my internal struggle. This is racism, or this is poverty.”

Then the challenge is: what can you do about those? At a larger level, outside the immediate clinical setting, there is advocacy. There are things you can do to intervene on behalf of a person—to get them access to resources, to push back on the lack of resources.

For us clinicians, even if we intervene at the individual level, like, “You’re living with racism, you’re not going to make that disappear,” just being aware of it helps. Finding solidarity with others helps. Having strategies for what you can do helps. A practitioner has to become familiar with them and give good examples of ways to deal with them to make sense of them. And then, there can be small structural changes.

To do that properly, we helpers need to have the right picture of the world—a complete theory that includes those things. In Canada, we have a long history of the government systematically oppressing Indigenous peoples. It was part of the policy: “The Indigenous people are all primitive. We’ll take kids away from their homes and put them in residential schools at the age of five, and they won’t see their parents anymore. We’ll just teach them how to be good little Euro-Canadian kids.” Predictably, this had very painful effects for many people.

Now in Canada, there has been a recognition of this history. We had a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, a formal apology. We had a whole process of reconciliation and restitution that is ongoing, and the Commission declared that Canada had committed cultural genocide. That’s very powerful and painful language for people who think of themselves as moral beings. It’s an important step in terms of helping communities.

Just last week, there was a government meeting with the people of Haida Gwaii on the West Coast. The government returned to Haida Gwaii ownership of the island that they’ve had since time immemorial. These kinds of concrete, politically and economically meaningful, redistributions of power do happen.

Ayurdhi Dhar: You have written about the importance of language and metaphors, and how people’s experience is shaped through these. Let’s talk about the language of historical trauma. This concept has been misused and co-opted for Indigenous people. What are the effects—the looping effects—on their identity when they are construed through deficient statistics and constantly called “traumatized”?

Kirmayer: There are several layers to this. It starts with what you said—that we use certain language, metaphors, and models to describe a reality that is always more complex than those models. The metaphor of trauma now means emotionally violent events that leave their marks on people. But by reifying trauma, we ignore the point that Mel Konner made: that throughout human history, from the earliest evolution of human beings, we faced violent environments, and we have resilient systems. We have coping systems, so these events don’t necessarily destroy us every time.

That’s where we should start—by acknowledging that the world is tumultuous and that life is going to be marked by grave difficulty. Oftentimes, we’re able to keep going. That doesn’t mean it doesn’t hurt us, or that we’re not wounded. We should begin from the position that these events don’t necessarily mean people are now completely stuck.

Many Indigenous people make this point: “Yes, we’ve faced repeated violence and disqualification, and we’re still here. We’re still holding on to aspects of our tradition, even though those were deliberately targeted.”

That’s what historical trauma is trying to point to—not just one moment of overt violence, but the structures that ground us down and disenfranchise us.

The critique I have is this: that’s all true, and it’s important to name that, but there are also ongoing structural problems. Talking about it historically is not the whole story. People in North America adopted this metaphor of historical trauma partly because of the influence of discussions around the Holocaust. But in that instance, most of the people who survived moved away and rebuilt their lives in other environments.

That’s very different from what has happened for Indigenous people who remain on their land, and who are being displaced to make room for a city or something else. They have no place to go. It’s a very different dynamic, and there is ongoing inequity. The concern is that when we use a metaphor like historical trauma, we are trying to mobilize an understanding that there are powerful external forces causing people’s suffering.

This model, however, is only going to be a partial model. Trauma theory can overly simplify how people respond to trauma. Rather than seeing how people find ways through this, individually and collectively, we can get stuck in a rigid model.

Again, many people have adopted the psychological idiom, and then it pushes aside the political. The question is: how do we find the interplay between these? It’s helpful to have a way to manage acute suffering and to understand the disruptions people experience with trauma. But understanding the ongoing adversity people face is equally important.

That’s where my interest in metaphor and language has two sides: the language we use to make sense of problems professionally, and the language we use individually every day. Those two things play back and forth. I can adopt the word “trauma,” and suddenly it becomes the way that I’m looking at my own world.

Any metaphor or model is always a partial truth, and it is always going to have tradeoffs.

It will reveal some things, and it will hide other things. Rather than saying, “Here’s the right metaphor, this is the one we should use,” we should also ask, “But what is this leaving out?” That word might come with extra meanings that aren’t right for the situation we’re in, or it might exclude something that should be in the foreground.

We’re better off having many metaphors. That’s part of what we do in therapy—helping people generate more metaphors and asking, “Does this one open a door for you that the other one didn’t?”

Ayurdhi Dhar: I remember reading somewhere that in a post-therapeutic world, therapists would be curators of narratives, and I thought that was beautiful. What are some of the narratives in the Psy disciplines that are just cultural narratives, but we see them as unshakable truths?

Kirmayer: The problem we have is still this ontology that says physical things—Western biology—are real, and that’s where the action is. Language and meaning are considered after the fact. We need to recognize that the ways we look at and interpret this complex world are constitutive of a lot of what is going on.

If we say, “I now pronounce you man and wife,” we’ve created a new kind of institutional relationship that has all kinds of concrete consequences. If we say, “You have a psychiatric problem,” or “Your diagnosis is such and such,” we’ve created a situation that a person can now work with, for better or for worse. Maybe that label opens doors to get some help, but maybe it also has unintended consequences: that people are now disqualified in a certain way, or that they don’t look at other options, and so on.

Language is important, but it’s not the only thing. We live in a world of material structures, of other people, of things that are not just mediated by language. But a lot of what we do is mediated by language. Taking that seriously means we should choose our words carefully and pay attention to what we are emphasizing.

We turn our metaphoric lens to one corner and throw something into relief; at the same time, other things remain in the shadows that we’re not paying attention to. So we need that metaphoric mobility.

We should pay attention to what poets have to tell us—those who are trying to generate really fresh metaphors and startle us awake with a kind of new view. That could be an important source of individual or collective healing, of getting out of the box.

For example, we hear that our economy is growing. Why is it good for an economy to keep growing? The only thing that grows without bounds is a tumor. There are people working on green economics who are talking about what it would mean to live in balance, so that things are distributed more fairly and people have the option to pursue things that are not all about material accumulation, but about the aesthetics of life, about moral values, about building together. That challenges a very core metaphor we hear repeated all the time and used to justify all kinds of political decisions.

Dhar: In Hindi, the language around alcoholism is different. Instead of being an “alcoholic,” as one would say in English, in Hindi, you would say “s/he drinks too much.” It’s not an identity but an action. It is common to find people who were heavy drinkers, then stopped, and later drank only occasionally, because there is no narrative constantly reinforcing that you have failed if you drink occasionally.

Kirmayer: Yes, that absolutely is a beautiful example. The challenge lies between that view, which seems to give us an opening and possibilities, and the fact that not everything yields to our language. People could have the best language and the best intentions and still be up against very obdurate problems.

**

“The only thing that grows without bounds is a tumour”.

D.S.M. in a nutshell.

Report comment

DSM is not all of the malignancy of this malignant growth disorder; the real problem is capitalism, the creator of poverty, privation and marginalization of anyone different from the dominant mainstream cultural delusion, whichever one that would be.

Report comment

Dear Elderly Survivor,

I agree that capitalism, poverty, and marginalization are significant causes of social distress. However, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental ‘Disorders’ (DSM) is used to marginalize individuals and dismiss the real causes of human suffering. This can be viewed as actively contributing to the very problems we face.

Moreover, accepting any diagnosis from the DSM tends to perpetuate this social issue.

Kind regards,

Cat

Report comment

The mention of medical anthropologists in medical school reminded me of now retired author Mary Doris Russell who wrote The Sparrow an extended overarching metaphor told in multiple thematics.Sex abuse is part and parcel and recovery as well as moral injury on a short and eons long basis.

She was a medical anthropologist and taught at CWRU Medical School and was fired along with many people including my children’s future basketball coach.

Her own story and all her novels must reads.

Report comment

I enjoyed your thoughts about the usefulness of metaphors: how they can not only help identify problems, often reaching another level of consciousness, bypassing psychological and cultural biases, and offer the possibility of creative solutions.

Report comment