Imagine attending two dinners over two days. On the first night, you see one man sitting by himself, 19 at a second table, and 80 at a third. You start to feel sympathetic for the man by himself; then waiters rush over and bring him carts loaded with 30 dinner plates of turkey. At the table of 19, each person gets three and a half dinner plates. At the large table the people at the far end, who get the least, get one half of a dinner plate of food. The mood is edgy.

The next night you are surprised to see something different. The man by himself gets 20 dinners. The 19 at the second table get two. At the big table, even at the far end, where the poorest people sit, each person gets one plate. People seem less anxious and less angry.

The first dinner echoes the distribution of income in the United States (with one plate of food equal to 1 % of income) among three classes. As Perrucci and Wysong suggest, there is a corporate class, which owns a large portion of the economy (1%), a credentialed class (19%), and a working class (80%). The second dinner echoes the distribution of income in Japan: there are still three classes; but the gap between the richest and the poorest is much less.

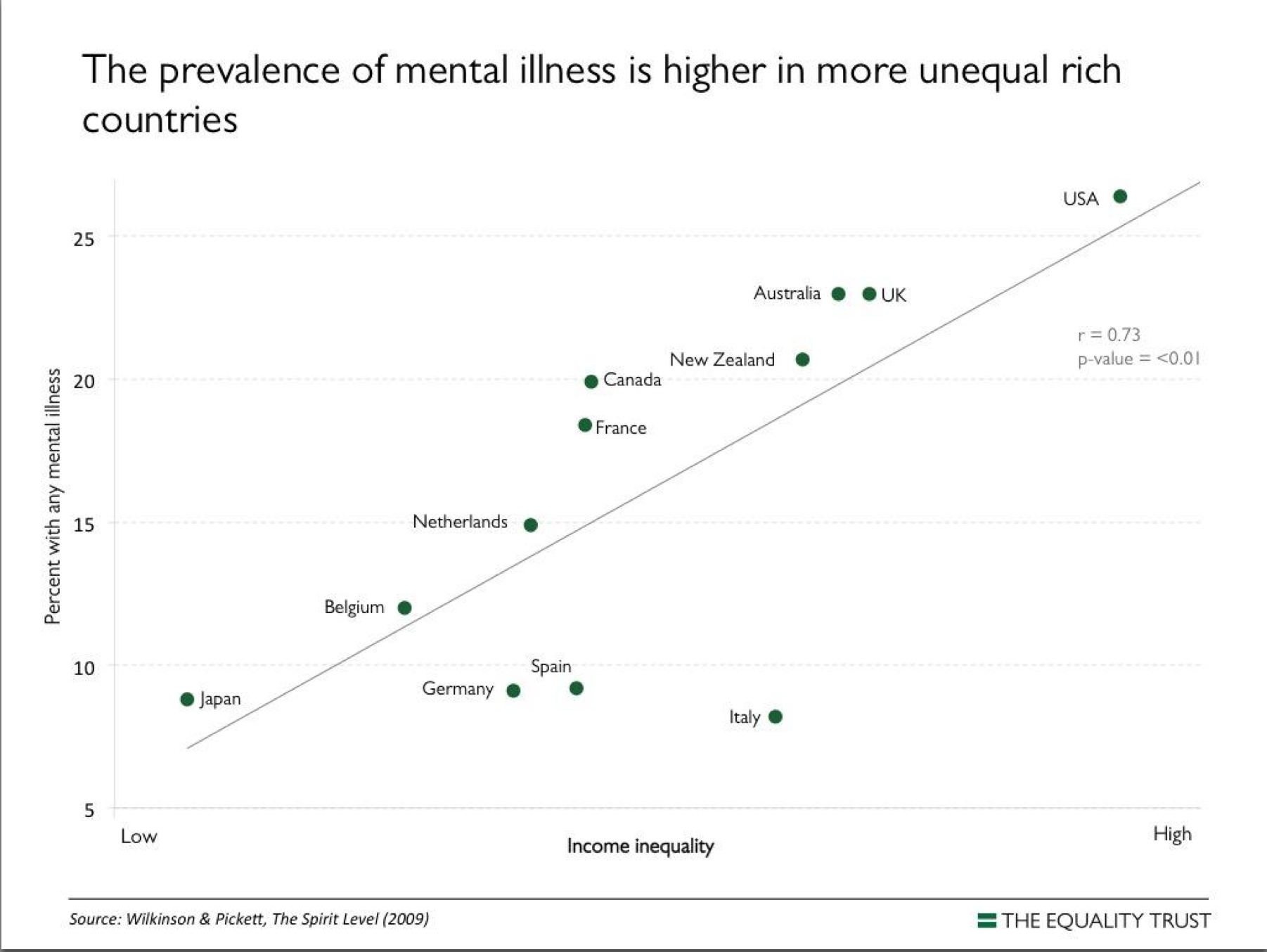

Now- your imagining is not yet done- consider what would happen if people in the United States were able to bring about greater income equality, akin to Japan’s. The rate of mental disorders would drop by half. Life expectancy, even of the upper middle class, would increase. There would be more trust, fewer homicides and fewer prisoners. These are some of the well documented effects of increasing income equality, as the social scientists Roger Wilkinson and Kate Pickett explain in their book The Spirit Level, and on their website, equalitytrust.org.

We would want, as therapists or clients, I believe, to contribute to lessening income inequality. We can support a system of care based in mutual aid among people facing common problems. This system allows people to get help and also to undertake collective action to lessen the inequality at the root of so much distress.

In a mutual aid health care system people assess themselves with the help of friends and family. People in distress would consider whether they were feeling desperate, that is, suicidal or violent or medically ill. If so, going to a professional would make sense. If not, using an idea of the Italian democratic psychiatrist Franco Basaglia, they would put in parentheses- brackets- the question of diagnosis (maybe later they would take off the brackets to consider diagnosis again). This allows them to consider other ways of thinking about their trouble or crisis.

Many crises stem from workplace difficulties. For example, lets say you have worked in a factory, had an injury and are now trying to get disability payments. You and your family are under great stress. You might then go to an injured worker’s program of the sort run in Maine in the 1990’s. The meetings had three parts. First, you would meet with others in similar situations with a moderator to talk about the experience of being injured. Second, you would meet with someone who could help you pursue getting disability payments. Third, you would be invited to a meeting to discuss ways to change laws so that workplace injuries were less likely. The program, in a simple brilliant way, kept the solution to human problems close to the causes.

As useful as this program was for you, it might not be enough. You might think the crisis is also about the direction of your life, and speak to your wisest friends. Perhaps later you might think that diagnosis, say, of obsessive-compulsive disorder, could help. At that point you have removed the brackets from the question of diagnosis and consulted a professional. But along the way the system of care has supported greater income equality.

If we decide that we want to support a mutual aid health care system in order to bring about greater income equality, we need first to understand the obstacles to achieving this goal and how to overcome them. The corporate class – like dominant classes before them, use two types of power to oppose greater income equality. Following Machiavelli, Antonio Gramsci suggests that power is like a centaur, half beast, with a human face, a combination of force and consent. To win consent, the corporate class- a tiny ultimately weak minority- needs to persuade the majority that extreme inequality is good or natural. To do so, this class argues for a set of ideas about human nature and society that takes extreme inequality for granted.

The corporate class employs professionals such as teachers, scientists, and doctors, as well as therapists, to help persuade the working class that extreme inequality is the norm and discourage opposition to it. Imagine you are the worker I mentioned earlier. Instead of going to an injured worker’s program you go to a mental health clinic. Instead of talking about common problems, people in the waiting room do not look at each other. Then the kindly counselor ushers you into a room where you, alone, get a diagnosis of a problem that is inside you. Counselors working in this way head off two challenges to inequality, Vicente Navarro would say. They separate people who might unite in collective action. And by defining distress as individual disorders, they make social analyses of distress less legitimate.

Keeping in mind these obstacles, therapists and others could organize to foster mutual aid health care systems and greater income equality. One useful way to plan change is to think of mental health care system as a pentagon, to borrow an idea from Robert Castel. The five points represent theory, united groups of practitioners and service users, laws, institutional structure and practice (a mnemonic is TULIP). Castel says that the lines between these points count the most. You can pass a law protecting the rights of service users, but you also have to see to it that the law is enforced and changes practice. You can develop a theory that places problems in a social context; you’ll also have to change institutions so that the theory can be practiced. I say “you” but I don’t mean you by yourself. As one leader of a new political party told me, “Don’t act alone.”

Some therapists in various disciplines, including psychiatry, will say that they have nothing to do with the maintenance of extreme inequality. In fact most professionals- teachers, ministers, doctors, journalists, scientists and others -will say the same thing. To accept all these claims one would need to say that millions of people in hundreds of influential occupations have little to do with maintaining severe inequality. That cannot be true. After all, the 1% is just 1%; they need a lot of help to appear strong and legitimate.

You may also say that I have focused on the effects of increasing equality of income within rich countries while increasing equality in the world seen as a whole is a much more urgent goal. You would be correct. Imagine attending a dinner of 100 where the food was distributed in proportion to income in the world. One person would receive 56 dinner plates, 19 one plate and a side dish, and the other 80% two soup spoon-fulls of rice. How to foster greater global equality is a question for us as citizens. As therapists, during our work week, we might consider developing mutual aid health care systems similar to those in countries where people earn the median global yearly income of $2,000 per year. By creating effective inexpensive systems of care for everyone, we’d be a small step closer to a world where all can live modestly and well.

In summary, in many countries citizens believing in greater income equality have followed the labor union maxim “Educate, organize, act.” As a result they are living longer healthier happier lives. There are promising movements of service users and therapists that are continuing in that tradition. You can join, or decide not to; in either case you’d do well to recall that more is at stake than your own future.

* * * * *

References:

Alvaredo, F. et al. (2013). The top 1 percent in historical and international perspective. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 27 (3) 3-20

Congressional Budget Office (2013) The distribution of household income and federal taxes. 2010. Washington D.C.: Congressional Budget Office.

Ballas, D.. et al ( 2013). Social cohesion in Britain and Japan. Social Policy and Society, 13, 103-117.

Basaglia, F., Scheper-Hughes, N. and Lovell, A. (Eds.) (1987). Psychiatry inside out: selected writings of Franco Basaglia. New York: Columbia University Press.

Castel, R. (1988). The regulation of madness: the origins of incarceration in France. Berkley: University of California Press.

Kellman, P. Maine Labor Group on Health (2006). Personal communication, on injured workers groups in Maine

Navarro, V. (1976). Medicine under capitalism. New York: Prodist.

Ortiz, I & Cummins, M. (2011). Global inequality: beyond the bottom billion- a rapid review of income distribution in 141 countries. New York: UNICEF.

Perucci,R. & Wysong, E.(2003). The new class society. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Robinson, W. (2004). A theory of global capitalism. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Wilkinson, R. & Pickett, K. (2009). The spirit level: Why greater equality makes societies stronger. New York: Bloomsbury Press. See also the website of the Equality Trust, and a TED talk by Roger Wilkinson.

Wright, D. (2013). More equal societies have less mental illness: what should therapists do on Monday morning? International Journal of Social Psychiatry, published online first, 22 July 2013

This kind of stuff always sounds great but we always seem to end up with big oppressive wasteful government stuff with these redistribute the wealth ideas and why should I work extra hard if someone is just going to take the extra benefits away from me and my family ?

I have had bad experience with things like the DMV , the court system ect, less govt the better I think.

Report comment

In the book, The Spirit Level, they said there was more than one route to more income equality. One way is for the state to tax high earners and redistribute through benefits, state jobs, and also minimum wage legisltaion. This happens in Sweeden for example.

The other is for the initial pay levels in a society to be fairly near each other. This happens in Japan.

So it does not have to be about the government.

The book also said a big link to financial equality in a country was linked to the level of trade union membership. So that is about working people having an impact on the economy and government.

The book also pointed out that working hours are less in countries with more income equality. So people work less hard for similar benefits and easier lives

Report comment

I think these points are all super important, and was glad to read them. I would add that people who want less inequality may also want to support/join/form worker-run, worker-directed co-ops. If all the employees in an enterprise run the enterprise, it’s highly unlikely that they will decide to let one or several persons accumulate all the wealth while the rest starve.

Report comment

Oops, I meant “worker owned, worker directed”!

Report comment

Thank you for the summary of these important points.

Report comment

For people who are think that the government should be small, a mutual aid health care system has advantages. Donald Light described such systems in Germany in the nineteenth century. These days such a system would be democratically controlled by its members, while keeping an arms length from the state, the professions and corporations.

Report comment

Hi Copy Cat;

Equality of outcome of necessity requires Collectivism.

Equality of emotions of necessity requires . . .?

PPACA illustrates perfectly the impossibility of equality of outcome strategies. They require massive Govt. bureaucracies and massive Govt. Intervention/Control/Redistribution. And all they have ever produced is massive misery, poverty, and death.

Here are some essays on the subject.

http://psychroaches.blogspot.com/2014/04/social-justice-defined-why-you-dont.html

And here is Social Justice hitting the street, as it relates to behavioral control/mental health:

http://psychroaches.blogspot.com/2010/09/i-am-law-paramedic-has-them-locked-up.html

Report comment

Thanks

I am not that good at politics but I sure get it,

It seems to me like a no win situation becuase the right or the Republicans I believe are behind the war on drugs and built the worlds largest prison system and police state.

I found this site searching Justina Pelletier Boston Children’s hospital kidnapping

Police State USA is a volunteer, grassroots journalism hub dedicated to exposing the systemic formation of an American police state. A team of contributing authors has been built based on their ability to exhibit professionalism, accuracy, knowledge of the subjects, and passion for the liberty movement.

http://www.policestateusa.com

Creating More FREE Societies Decreases Mental Illness !!!!

Report comment

Thanks Copy Cat, I hadn’t seen that one.

The CATO Institute has one too.

http://www.policemisconduct.net/

Report comment

” The corporate class – like dominant classes before them, use two types of power to oppose greater income equality. Following Machiavelli, Antonio Gramsci suggests that power is like a centaur, half beast, with a human face, a combination of force and consent. To win consent, the corporate class- a tiny ultimately weak minority- needs to persuade the majority that extreme inequality is good or natural. To do so, this class argues for a set of ideas about human nature and society that takes extreme inequality for granted.

“The corporate class employs professionals such as teachers, scientists, and doctors, as well as therapists, to help persuade the working class that extreme inequality is the norm and discourage opposition to it.”

“Some therapists in various disciplines, including psychiatry, will say that they have nothing to do with the maintenance of extreme inequality. In fact most professionals- teachers, ministers, doctors, journalists, scientists and others -will say the same thing. To accept all these claims one would need to say that millions of people in hundreds of influential occupations have little to do with maintaining severe inequality. That cannot be true. After all, the 1% is just 1%; they need a lot of help to appear strong and legitimate.”

This is all very true, and shameful, since it is essentially the opposite of the belief system upon which the US was founded. And in addition to the professions listed as “employed” (controlled) by the 1% is now the US government, and it’s employees. It’s a shameful display of greed and propaganda that is being perpetrated against the American people these days, by the corporate elite. And as you mention, the corporate class “argues for a set of ideas about human nature and society that takes extreme inequality for granted,” and this is the DSM belief system. So the psychiatric practitioners are far from innocent. And some day, even those helping the corporate elite, will be harmed by them, if things continue in this manner. Don’t be fools, the corporate elite doesn’t care about you either.

Thank you, Charles, for this blog pointing out how, and the problems that arise when, a country is taken over by the apparently, now completely unethical and uninsightful, corporate elite. I do think a comparison graph of where all countries stood, say in 1980, would further prove your point, and give a better frame of reference.

Report comment

You might notice that it is the English speaking nations (except Canada) where this inequality is greatest. Germany which is the richest nation in Europe is almost like Japan in terms of mental illness. A different ethos. Nations with a higher Catholic populations are less likely to revile the poor.

But in America money is king. People have an exaggerated idea of what money can do.

And they fear the reproaches they will receive if they get low on money. No sympathy for those out of work. Calvinism is a big factor. Are you of the Elect?

Money creates a false sense of independence and of detachment. What people really want can never be gotten through money which is self assurance and genuine security; but those valuable conditions are a matter of character and experience.

Report comment

Karsten Struhl who teaches at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York (and is speaking at the Left Forum on May 30) would have a response to your comments. He argues that very unequal capitalist societies depend in part on a concept of the isolated self competing with all others. To create a more equalitarian society then requires us to consider, as Buddhists do, that the “self” is an illusion.

Report comment

Interesting article Charles, and i totally agree that the ‘intellectual class’ (the 19%) might want to consider the position they have in maintaining wealth inequality.

The way i see it is that the slave master (the 1%) are not really the biggest problem. It’s the overseer, the man with the whip (the 19%) whose greed results in the most pain for the remaining 80%. Blaming the boss man ain’t going to cut it if we get organised and decide to resist. We will not forget the brutality dished out to us by police, prison officers and mental health workers etc.

Collective action, we should all talk to each other more. The internet has made this possible.

I wonder what Antonio Gramsci and Machiavelli would have made of this development in technology lol.

Report comment

I like that “the 19%” the police, prison officers and mental health workers … people who will hurt you and say well sorry but “I am just doing my job”.

You nailed it with that one.

Report comment

The 19% : “I’m just doing my job” – an all purpose excuse invented by the NAZIs that can be used by anyone who doesn’t want to take responsibility for their own actions or even consider that what they’re doing might be wrong. It’s as if the person who’s just doing their job isn’t a real person with the ability to make choices and moral decisions. Instead they’re just an unthinking cog in the government machine with no more choice or responsibility than a photocopier or fax machine.

Report comment

“I am just doing my job” = “I’m just following orders”.

Humanity has heard that line before…it never changes:(.

Report comment

I agree . For me, the more I blame, the less energy I have for organizing.

Report comment

Japan covers up their mental illness. Suicide in Japan is at 26 deaths per hundred thousand (2009) versus 7 deaths per hundred thousand in Netherlands. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Suicide_in_Japan.

The prevalence chart is inaccurate.

Report comment

More on Japan “Most of the involuntary sterilizations were performed on inmates of psychiatric hospitals and institutions for intellectually disabled people.” http://www.lit.osaka-cu.ac.jp/user/tsuchiya/gyoseki/paper/JPN_Eugenics.html

Report comment

On the website of the Equality Trust, Roger Wilkinson and Kate Pickett describe how they arrived at an estimate of the rate of all mental disorders-not only the suicide rate- in different countries.

Report comment

Suicide has always been an acceptable choice in Japanese culture, much as it was in the Roman culture. Of course, when America occuppied Japan after the war we tried to pathologize everything in their culture that we didn’t agree with, especially suicide. One has to be careful what one accepts concerning all of this and one should go to the horse’s mouth to learn what’s going on here. Because of a huge difference in religious and cultural beliefs, suicide has never been seen as something bad in Japanese culture.

Japanese culture didn’t have a word for “depression” until the drug companies and American psychiatrists saw this culture as a lucrative plum to pick in the world market. So the drug companies and American KOL psychiatrists promptly hied themselves over to Japan and began convincing everyone that they suffered from “depression.” SSRI’s became a booming business. This is truly sad since the Japanese had a very good understanding of sadness and how to deal with it. An entire period of Japanese history was devoted to the comtemplation of the quality of sadness, especially in the lives of humans because of the shortness of our own sojourns here on earth. This is why the cherry blossom holds such prominence in Japanese visual art, poetry, etc. The cherry blossom, as beautiful as it is, lasts only a short time and with the first breeze the petals fall onto the flowing waters of the stream, to disappear from sight and our awareness. I think it was called the Edo Period. Anyway, American consumerism, psychiatry, and the drug companies quickly took care of all this maudlin stuff and convinced everyone that this was a sure sign that they were depressed and heading for worse things, like the big bp and the horrible s. Totally disgusting. I think there’s a book about all of this by a man named Evan Waters.

Report comment

I should have made more clear the reasons for telling a story about Japan and the USA. I wanted a vivid illustration of the beneficial effect of income equality on mental health. I could have picked other countries to compare.

Report comment

Right, I understand. My response was to markps2.

Report comment

This is timely.

I’m crying my eyes out in the midst of Klonopin withdrawal because I cannot relate to anyone on the BenzoBuddie boards. They all have houses, cars, families-microwaves even. I’m recieving disability after being diagnosed ‘bipolar’ after an abusive divorce where I lost EVERYTHING-my home, my kids, my business, my profession…I have not recovered from all that loss and the message I continue to get is I’m suppose to slap myself around and ‘get over it’. I cannot feel close to anyone. I cannot relate to people who take vacations and watch DVDs via their ‘entertainment’ centers.

I am utterly absolutly on my own and this withdrawal just points out how useless it all is. I can’t sleep, I can’t be around people without freaking out I’ve lost empathy for myself and others. I want to die.

I wish the 1% would send me the black pill cuz I ain’t doin’ a thing for them.

If only I’d had some help getting away from my abusive husband-if only my family hadn’t abandoned me..if only life wasn’t just about money.

Report comment

Human being,

I also was misdiagnosed as bipolar. My marriage was destroyed by a psychologist and psychiatrists who lied to my husband claiming adverse reactions to Wellbutrin withdrawal was a “life long incurable genetic disease,” so they could aid in covering up the sexual abuse of my little child.

Their lies prompted my husband to take all MY money out of our home, resulting in the bank demanding, (within days after my husband’s untimely death, and without proper paperwork), I sell my home at the absolute bottom of the housing market. I lost my life savings, over $250,000 in home equity, in addition to my marriage being destroyed, due to psychiatric malpractice.

You’re not alone is your disgust at our societal worship of only money. Hang in there, eat healthy, exercise, have hope; you can heal in time. And your disgust is well founded. The truth, albeit with patience and perseverance, shall set you free. My prayers are with you, if that matters.

Report comment

Saying “I want to die” will get you locked up (hospitalized) if you say it to someone in authority. I guess you have not been locked up in order to be “helped”?

If you can’t be around people without “freaking out”, don’t put yourself in that situation.

If you exercise strenuously during the day, you will (have to) sleep at night. The sleep will not be great, but it will be sleep.

Report comment

Life is not just about the money, though it helps…

I hope you’re still hanging in there. When I had my total breakdown I was in dire straits as well – lost the job (or rather was not prolonged on a shitty time-limited contract), couldn’t afford the flat and had to move to a small shitty apartment by myself and was severely drugged and abused by the system.

This is just something one has to go through. “What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger” – it’s cliche but it’s also true. Don’t try to push yourself too hard, just get through the withdrawal first, your health is the most important. Picking pieces takes time…

Report comment

Your story poignantly illustrates a point made by Roger Wilkinson and Kate Pickett in the Spirit Level (p. 213). “For a species which thrives on friendship and enjoys cooperation and trust, which has a strong sense of fairness… it is clear that social structures which create relationships based on inequality, inferiority, and social exclusion must inflict a great deal of social pain.” Since very unequal societies are so socially dysfunctional, we perhaps can ‘feel more confident that a more humane society may be a great deal more practical that the highly unequal ones in which so many of us live now.”

Report comment

What Should We Do?

I say the key is to get off the grid as much as possible, for example you can get a long range wifi antenna and get internet free instead of getting a bill in the mailbox. Cutting cable is one of the the first steps.

http://www.turnoffyourtv.com/

http://science.howstuffworks.com/environmental/green-science/living-off-the-grid.htm

You can feed the machine and be it’s slave or you can build your own machine that feeds you, long range wifi antenna V.s a cable bill is the perfect example, solar wind stuff like that is cool too.

http://www.offthegridbuild.com http://earthship.com/

Living half a dozen paychecks away from disaster is a perfect recipe for anxiety / depression “mental illness”.

For example, If I can’t pay my light bill my solar panel will charge my battery bank going to a walmart 12-120 volt inverter to power this computer that can pick up free wifi’s a long way off. Those new Led bulbs use less that 10 watts and are bright, I won’t be in the dark either any time soon.

I want this thing next the 600 watt wind turbine,

http://www.walmart.com/ip/Coleman-48444-Coleman-600W-Wind-Turbine/15063163

Report comment

On the other hand there is something unbelievably freeing about hitting the bottom. When all your life you’re under pressure to always achieve and be the best, not having to care anymore is refreshing as hell. A good place to start a new life…

Report comment

Brilliantly put, great article.

In the words of Noam Chomsky:

“The prime target of condemnation in the labor press was what they called “The New Spirit of the Age: Gain Wealth, Forgetting All But Self.” No efforts have been spared since then to drive this spirit into people’s heads. People must come to believe that suffering and deprivation result from the failure of individuals, not the reigning socioeconomic system. There are huge industries devoted to this task. About one-sixth of the entire US economy is devoted to what’s called “marketing,” which is mostly propaganda. Advertising is described by analysts and the business literature as a process of fabricating wants – a campaign to drive people to the superficial things in life, like fashionable consumption, so that they will remain passive and obedient. “

Report comment

“Propaganda is to democracy what the bludgeon is to the totalitarian state” also Chomsky.

Coercion and force. We see the coercion daily in the media, force becomes necessary when people begin to organise. See the Occupy and Anonymous demonstrations.

The levels of fear and paranoia of the 1% seem obvious when we consider recent developments. Censorship with laws, violence to disrupt protests, and spying by the NSA. I think in psychiatric terms they are becoming delusional, and may be a danger to self or other lol.

Should the 80% restrain, incarcerated and medicate them before they hurt anyone? It may be necessary.

Report comment

We can respond to injustice in two ways.

First, we can respond in our role as citizens, as the comment implies. As a citizen I believe in using the 298 methods of non-violent action described by Gene Sharpe.

Second, we can also respond to injustice in our workplaces, including mental health clinics. I outlined a way to do this in the article.

Report comment