My wife once came with me on a Saturday morning visit to a psychiatric hospital. I was collecting data for my PhD, and she met me in the car park of a large psychiatric hospital after I’d conducted my interviews. As I drove away, she stroked the back of my hand and suggested that I could relax my knuckle-whitening grip on the steering wheel. I really didn’t like leaving the residents behind. I wanted to rescue them.

In mental health, resolving the relative contributions of our biology and genetics and how these interact with social and environmental factors (our parenting, peer-relationships, learning, and experiences of both abuse and nurturing) is more than an intellectual puzzle. I’m occasionally annoyed by what appears to be a rather simplistic suggestion that, if there’s a biological, even heritable, element, to a psychological phenomenon, then we’re inevitably discussing an illness, a disease.

Of course there are biological elements to every behaviour, thought emotion, or human trait, since they all involve our brains (we don’t, despite the jokes, think using any other organ and we do, despite the jokes, always use our brain when we’re thinking). But our attitudes to these issues also have direct personal implications. As a mental health professional, as a some-time user of mental health services and (like most of us) as someone with family members with more serious mental health problems, it’s certainly personal for me.

I’ve spent much of my professional life studying psychological aspects of mental health problems. Inevitably, this has also meant discussing the role of biology. I hope I’ve made some progress in understanding these issues, in working out how the two relate to each other, and the implications for services. That’s my academic day-job. But it’s not just academic for me. I’m probably not untypical of most people reading this; I can see clear examples of how my experiences may have affected my own mental health, but I can also see reasons to suspect biological, heritable, traits. As in all aspects of human behaviour, both nature and nurture are involved and they have been intimately entwined in a complex interactive dance throughout my childhood and adult life.

I need to be cautious, because I don’t want to say anything that will irritate my siblings, but I do think there were oddities in my upbringing. My parents had very strong religious beliefs, and I think it’s fair to say that, in addition, there was a degree of emotional repression and our family relationships were somewhat complicated. Just one example: my parents’ belief system included the need to love God more than anything or anyone else, including one’s children. So, after my mother’s death, we discovered that, when she had confessed to a religious mentor that she was in danger of loving her children more than God, there was a subsequent process of re-adjustment … she was encouraged to practice loving her children less. My parents rejected the material world as merely a stepping-stone to heaven (or hell) and paid little attention to worldly pursuits. I remember opening a letter from Cambridge University confirming an offer of a place as an undergraduate. I told my mother, whose reply was; “Very nice dear, now, do you want baked beans on toast for breakfast?” Pride was a very worldly emotion. I guess that experiences like that must have had an effect on me and my siblings.

So much for my upbringing. But like all of us, I was also born with a particular brain. I’ve been educated to observe signs of neurological as well as psychological functioning (if those two concepts can be separated). And one of my close relatives has had major mental health problems throughout his (and therefore my) life. So it’s intriguing to observe similarities between us and speculate on their origin. Do we behave similarly because of our shared upbringing, our shared genetic heritage or (of course) both?

A Phenotype

So I am emotionally labile; my self-esteem and emotions are very fragile and very much dependent on what I imagine other people are thinking. Or, at least, I think I am; my observations of my own behaviour are themselves subjective, and it’s possible that others do these things as much as I do. I frighten myself (given my relative’s experiences) by fantasising about … winning Nobel prizes, winning Pulitzer prizes, being elected to this and that, being awarded knighthoods … and that’s frightening because I’ve seen self-referent fantasies ruin other people’s lives. My selective attention is terrible and I find it difficult to avoid distractions. Those who know me well will know that I work with the BBC rolling news constantly running in the background, and I frequently play games while on the phone. I appear to have problems with face-recognition; I find it almost impossible even to recognise the faces of people whom I know well.

And when in conversation with people (in what seems to me to be a potentially related phenomenon), I find it difficult maintain eye-contact, and look to the side to line-up images in the distance. And, perhaps most saliently, I lurch forwards and jump to conclusions in my mental logic. So, if you give me the sequence “A, B, C” and ask me to complete the sequence, I’ll say Z. Maybe that’s a bit of a joke (a pun on ‘complete’), and it’s unequivocally good for me in my academic career. A creative professor is a good professor. I also and simultaneously make abstract and surreal connections. It’s a recognised part of my teaching style – I’ll veer off on a tangent. Again, perhaps useful in an academic and possibly engaging or at least entertaining for students (if they can keep up…). But jumping to conclusions, tangential connectivity and abstract, ‘clang’ associations all have very interesting connotations in the field of mental health.

So I am very interested (and, I hope, open-minded) about what it is, if anything, that we inherit. How do I differ from other people? What proportion of the variance in these traits can be accounted for by genetic differences? What proportion of the variance in these traits comes from being brought up by repressed religious extremists? What proportion comes from being reinforced, through my childhood, for being academic? Which elements of my upbringing were different other people’s anyway?

Gene x Environment Interactions

My tentative conclusions, as of today, are these: First, my childhood had at least as many oddities and peculiarities as would capture the attention of any competent psychotherapist. Second, I believe that my professional eye has identified interesting phenotypes in my close family that reflect potentially heritable traits. Third, these traits may well put me at risk of many emotional problems. Incidentally, they may well also make me absolute hell to live with, and I must give credit to those who have given that a go. Fourth, the interactions of these heritable and environmental factors in my development have also created a person – me – that I value and respect. That’s a very odd, solipsistic, thing to say, but it’s important.

Which leads to my fifth and most important conclusion. For some people, such as for my relative, these interactions cause problems. For others, like me, a presumably very similar pattern of interactions has observable similarities but different outcomes. Of course we need to consider the contribution of biological as well as environmental factors in our psychological makeup. I think it’s perfectly possible to be intelligent and open-minded about the contribution of genetic and environmental factors in our mental health. We can intelligently and respectfully discuss how experiences and heritable traits can interact to produce the wonderful variety of human experience. This, I think, is a much more accurate and helpful way to conceptualise what’s going on than to say that some of us – but only some of us – have ‘mental illnesses’. Labels such as ‘schizophrenia’ not only suffer from the validity problems that we’ve discussed elsewhere [URL], but also obfuscate these important considerations. I don’t think it’s helpful to consider how I have managed to avoid developing ‘schizophrenia’, or whether I have ‘attenuated psychosis syndrome’. To do that, to reduce these discussions to binary considerations of the presence or absence of disorders, necessarily constrains the scientific debate. It can also sometimes have frightening consequences in the real world. When I’ve mentioned some of these issues before in less public settings, friends and colleagues have often told me that I’m being brave, and that it’s a potentially risky topic of conversation. So why might that be?

The Eradication of Undesirable Genetic Traits

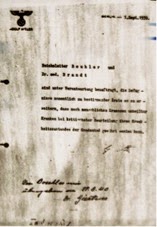

Part of the reason that people might be reluctant to talk about such issues is that we have a very poor track record in this area. This is a difficult topic, but I think it is important to remember the infamous 1933 Nazi Law for the Prevention of Genetically Diseased Offspring (Gesetz zur Verhütung erbkranken Nachwuchses). Arguments of genetic science not only led to the drafting of this law (which permitted the compulsory sterilisation of any citizens who were judged to possess a ‘genetic disorder’ which could be passed onto their children) but indeed led German-American psychiatrist Franz Kallmann to argue that such a policy of sterilisation should be extended to the relatives of people with mental health problems (in order to eradicate the genes supposedly responsible). The notorious Action T4 ‘eradication’ programme was the logical extension of these policies.

[Note: on the left, the Reich Law Gazette on 25 July 1933: Law for the Prevention of Genetically Diseased Offspring; on the right, Adolf Hitler’s order for the Action T4 programme.]

Of course, a focus on biological aspects of mental health problems is not in any sense necessarily synonymous with fascism. But for many of us, there are echoes of blame, of stigma, when we identify the pathology within the genetic substrate of the person. I’m reminded of Eric Pickles’ notorious throw-away comment to a voter campaigning about the abuse she’d experienced that she should “adjust her medication.” If the pathology lies in the person, and particularly if it is a biological problem, we can dismiss any further troubling considerations.

So one way to understand these kinds of experiences is to diagnose some form of ‘subclinical’ syndrome, perhaps attenuated psychosis. If the Nazis had won the second world war, I would have been castrated as a first-degree relative of a ‘schizophrenic’. Disease-model, eugenic, thinking is a direct threat to me personally, especially given the recent rise of UKIP and other far-right parties in Europe. I am interested in whether the traits that make me a good professor may also be related to the traits I listed earlier, and on their impact on my emotions. I am interested in whether they may have emerged from a similar mix of genes and environment that led my relative to experience psychosis. I am very interested in the practical implications; I have always, for example, avoided certain classes of street drugs. It is absolutely possible to discuss gene × environment interactions, but – please – don’t use the ‘disease-model’ as a framework.

Acknowledgement: Thanks to Anne Cooke for helpful comments and advice on earlier drafts.

I’m pretty vocal about my reservations regarding academia, for a variety of reasons, but I really appreciate the personal element you bring into this, regarding your own family dynamics, beliefs, practices, and upbringing. To me, that is always most relevant, as it teaches us, by example, how to respond to life.

Often, what we learn by example is not the best way, and it can take a while, going through life, to recognize that we have this split happening–between how we were raised to respond vs. how we would naturally veer toward responding to life’s experiences, as per an expression of our own unique individual spirit. I know that for me, it has felt like breaking away from the family patterns is almost like betraying my family, when in essence, it is just me finding my own voice, heart, and spirit.

One thing I take issue with in this article is where you say that we don’t think with any other organ than with our brains. I have come to believe, from my experience of healing, that we actually ‘think’ with our hearts. While our brains are, perhaps, a measure of intellectual intelligence, our hearts are a measure of emotional intelligence, which I feel influence our intellect and perception a great deal. Our beliefs and thought patterns are most influenced by how loving, kind, and generous we have feel toward ourselves and others, as well as how much of these we have had shared with us by others, especially by the adults whom surrounded us as children. I believe the level of pure gratitude we carry with us also greatly influences our thinking and perception.

What you describe sounds like what I would call ‘withholding love,’ which would be traumatic and which would instill beliefs of not being worthy of love. That’s how I read your story about your family.

In turn, that would translate into all sorts of negative messages which would interfere with our perspective and influence our focus in a variety of ways.

Mostly, though, it ends up being a very deep seeded feeling of unworthiness. Once we identify this and shift into a more present time and self-affirming perspective, that of course we are all worthy of love, that it was our parents (or whomever) that had their own issues and beliefs which were, somehow, passed down to us, inappropriately, then we can forgive the past and come into present time with a new version of ourselves, as one that is of course worthy of love and all good things. That’s how we can rewrite our stories, heal from the past, and come into a new version of ourselves, aligned with our self-loving hearts. I have found this to be tremendously healing to anything, always uplifting.

Very interesting read, thank you so much. Stimulated my thoughts around all of this. Thanks for the personal touch, as well.

Report comment

I always love your comments Alex 🙂 I feel that we are on the same wavelength. Just when I have been pondering over something I log on and see you’ve posted almost the exact same thing I was thinking!

I completely agree about the “learned” responses! And you’re right, it’s hard to change until you stop and think about how you are responding and why. I have also found “heart work” to be extremely helpful and beneficial.

Report comment

Thank you Dr. Kinderman for a very interesting and thought provoking article.

My husband and I were also brought up in a rather harsh, religious style. I think this was very common back when we were young back in the 1960s. We were taught to think of ourselves as sinful and imperfect. Pride was considered a sin and we were never praised. We were subjected to harsh punishments both at school and at home. For many years I believed that this was the reason we both suffered from mild anxieties and depression.

When we had our own children in the 1980s we decided to try a very different form of child rearing. We were determined not to make the mistakes our parents and teachers had made. Feeding our children on demand, waiting longer to start toilet training, praising the most mediocre efforts were all encouraged as ways to help our kids achieve “self-esteem”. We followed the teachings of the age and were very proud of our high-achieving, well-adjusted children.

The last thing we ever expected was for one of our children to develop a severe mental illness. We thought we had done everything right. How could this happen to a young adult who had shown so much promise? How much is nature and how much is nurture? We have been seeking the answer ever since. I think you are correct in saying that it must be a combination of factors. I wish so much that there were more answers out there for those of us who keep questioning whether we did something terribly wrong or whether we are so genetically flawed that we should just stop having children.

Thank you for your contribution in looking for the answers.

Report comment

There are two things that come to mind: one is that research and “anecdotal evidence” both suggest that you should not prescribe to any extreme “parenting style”. Growing up in a family which enforces ruthless discipline is bad but growing in a no stress environment of absolute acceptance is just as bad, especially when the child gets out and faces the real world. That being said – there’s no perfect being a parent and fads come and go but it’s always a very personal thing which everyone has to learn and make mistakes at.

The other thing is that having “mild anxieties and depressions” is not mental illness. It’s called life and everyone (maybe save for some truly psychopathic individuals if those in fact exist) experiences those. I don’t know a single person who has not have a period in their lives when they could be described as clinically depressed and for most people this is a constant part of everyday struggle. Life isn’t roses and unicorns. Pathologizing this as “mental illness” is a different beast altogether. The point is: if you want to find “genetic mental illness” in the family – you will. There’s always going to be “oh, I think my grandma was depressed, she cried 3yrs after grandpa died” or “uncle John was weird and talked to himself” or wherever. It’s called confirmation bias and one of a thousand reasons why “psychological autopsies” are scam.

Report comment

Not to be nit-picky, but yes, you were born with a brain, and that brain has been changing non-stop since before you were born. Whatever genes we have, the expression of those genes is determined by environment. I’m not denying that there are medical causes of unwieldy or unbearable mental states, it’s just that the idea that there is any separation at all between nature and nurture is old-school and faulty to a degree that warrants its abandonment, but we don’t have the language to speak or think without the dichotomies of nature/nurture and mind/brain.

Sometimes, I think, we need some philosophical therapy to create our own new perspectives and paradigms to help us liberate ourselves from our past without dragging our parents into our psyche any more than we need to so that their traits no long matter, heritable or not. We we can stop being their children and take possession of ourselves.

Report comment

Dear Peter

KNOW THYSELF is ancient wisdom advice that most within our predominately Patriarchal, Misogynistic, Caucasian developed, educated societies, assume to be from Ancient Greece. That well known phenomena of HOW the winners get to shape our sense of how we got here, in this 21st century A.D. While a well travelled and experienced sense of that concise advice, comes to understand that it most likely stems from ancient Temples now buried under an ocean of sand, in the Sahara desert.

While ‘what is he on about’ will grip your obvious sense of reality, as you read this comment with the dichotomy of being human. The taken for grantedness of our actual experience. Specifically, HOW we forget our own life history and take our adult capacity for the spoken, written and read word, completely for granted. With no real memory of how our body created the “sensation” experience we label mind, in the process of our emerging functionality, as members of a survival economy, masquerading as society.

As you write of securing your place in this survival economy, “I was collecting data for my PhD,” and imo, developing a vocational world-view that “we’re inevitably discussing an illness, a disease.” While from the world-view shaped by actual experience, I would urge you to “pause” and contemplate your subconscious, survival oriented rationale, as you justify your own behavioural needs.

While from this vocational world-view perspective, I urge you to consider why, in the literature of a “treatment oriented” attitude to psychosis, there is no referential material, citing the latest view from “developmental science?” And why in the current early intervention attitude to first episode psychosis, there is a “paradoxical” view that dismisses earlier formulations of a “double-bind” theory relating to the family dynamic as a crucible of madness. While simultaneously pointing out that Expressed Emotion within the emotional dynamic a psychotic patient returns to, is a most accurate indicator of relapse.

Again I would urge you to pause and contemplate the “thermodynamic,” internal nature of how the constant reciprocal influences between your body-brain create your taken for granted experience of mind. While urging members of the survivor community to help the survival vocations of psychology & psychiatry to face the reality of our historical journey to becoming human. For as the great American writer Jean Houston points out, we are not yet fully human, still closer to the animals than the angels, in our subconsciously motivated survival behaviors.

A view of our common “existential” reality, to which I include an excerpt from my own existential resolution of psychosis, in terms of making sense of Dr John Weir Perry’s view that psychosis “is nature’s way of setting things right.” From my academic paper: Psychosis: Affective States of Consciousness & Nervous System Dysregulation:

“In 2007, I began a self-education process to understand the structure and thermodynamic functioning of my nervous system processes, and the non-conscious stimulation of my manic-depressive experiences. Including a continuous reading and re-reading of relevant literature like “The Polyvagal Theory” (Porges, 1995, 1997, 1998, 2001a, 2003, 2007, 2011) which articulates the discovery of “an integrated social engagement system,” (Porges 2001) and an adaptive perspective on psychiatric disorders:

The Polyvagal Theory provides a perspective to demystify features of clinical disorders. The theory provides principles to organize previously assumed disparate symptoms observed in several psychiatric disorders (i.e., a compromise in the function of the Social Engagement System). Moreover, by explaining features of disorders from an adaptive perspective, interventions may be designed that trigger the neural circuits that will promote spontaneous social engagement behaviors and dampen the expression of defensive strategies that disrupt social interactions. (Porges, 2009)

Leading me towards an experiential integration of developmental science knowledge, which has changed a self-defensive, treatment oriented perception of my genetic predisposition to experiencing manic-depression. Towards “a phylogenetic interpretation of the neural mechanisms mediating the behavioral and physiological features associated with stress and several psychiatric disorders.” (Porges, 2004) A shift in personal focus, towards understanding the “phylogeny of the autonomic nervous system,” (Porges, 2004) which brought a non-pathologic context to why “despite family, twin and adoption studies revealing a high genetic liability, with a point estimation of 81%, single major-effect genes have not been detected and the precise molecular aetiology of psychosis currently remains unknown.” (McGorry et al, 2012) Hence, my experiential research, has explored a dichotomy in the descriptive language used to define assumptions of brain pathology, and the nervous ease and “dis-ease” (Frances, 2013) of my lived-experience. A dichotomy evidenced by my pharmacological treatment resistance, with a long history of delusional experience, occurring both on and off antipsychotic medications. A long history of various medical diagnoses, hospitalizations, intolerable medication side-effects and no breakthroughs in the promise of genetic research, so painfully frustrating to my quality of life aspirations. A dichotomy of lived experience and diagnostic definition, which persisted until appropriate education enabled an awareness of my nervous system function, and the psycho-physiological content & context of an experience, historically labelled psychotic. Which, in the phenomenology of non-conscious organism function, and how “thermodynamics are not only the essence of biodynamic, they are also the essence of neurodynamics, and therefore of psychodynamics,” (Schore, 2003) views all descriptive language terms as the insubstantial labels, of our “affect” driven images of consciousness.”

This excerpt is included knowing that you cannot afford to consider such a view, in our current urban landscapes, of an economy masquerading as society, and that you need to keep voicing the public rhetoric, that justify’s prescriptive medicine practices and seeks funding for resources. A common dilemma that posses both sides of the “psychiatry anti-psychiatry” argument here on MIA, with the mask of consciousness “cloaking” funding opportunities, with the rhetoric of serving others.

We need more research! We need more treatment approaches!

All perfectly understandable in the common context of survival, and our historical denial of the body as a Temple of Being. within our predominately Patriarchal, Misogynistic, Caucasian developed, educated societies.

Sincere regards,

David Bates.

Report comment

Peter,

On the one hand, we have conventional psychiatrists who continue to insist in their simple, inaccurate, reductionist “chemical imbalance” theories… on the other hand, there are the critical psychiatrists who (understandably) want to see this nonsense come to an end.

In the meantime, nobody in the medical community is focused on addressing many of the *real* conditions that cause severe mental illness, psychosis:

https://psychoticdisorders.wordpress.com/bmj-best-practice-assessment-of-psychosis/

Trauma. Treatment for (emotional) trauma, that’s all I hear. While *physical* brain trauma is often never even assessed… A traumatic brain injury (TBI) ought to be a the top of the list, and an MRI ordered for each patient who shows up at an emergency room with psychotic symptoms. Checking for the use of marijuana, prescription drugs, street and OTC drugs; addressing sleep disorders. These things need to be looked at long before there is any assumption made…. including emotional trauma, and need for talk therapy.

I want to see conventional psychiatry gone. I also shutter to think of it being replaced by talk therapy, and *only* talk therapy. All the talk in the world won’t address a traumatic brain injury, or an adverse drug event.

Duane

Report comment

Duane,

Talk therapy is also of very limited (or no) utility where trauma is embedded in the body, and where body-based therapies (e.g., EMDR, sensorimotor therapy, neurofeedback) are more effective. Talk therapy has its place, but to make it the only option or the only alternative to drugs will result in more drugging for the simple reason that, far too often, talk therapy is not effective or appropriate. I really wonder if we would have ended up with the disastrous drug-based paradigm had orthomolecular therapy been taken more seriously.

Report comment

GetItRight,

I agree!

Bill Wilson, co-founder of AA was a big proponent of niacin (vitamin B-3).

And Dr, Abram Hoffer had enormous success with people who had been diagnosed with schizophrenia by using Orthomolecular (nutritional) Medicine.

Duane

Report comment

In fact, AA was as much a nutritional program as a spiritual one, at its onset.

You’d never know it today.

Go figure,

Duane

Report comment

Bill Wison, Orthomolecular Hall of Fame, 2006 –

http://orthomolecular.org/hof/index.shtml

And to clarify, I have no problem with a spiritual approach either. But I don’t think spirituality ought to be the *only* approach to sobriety!

Duane (sober since 1987)

Report comment

Duane,

don’t forget Dr. Carl Pfeiffer, the other orthomolecular pioneer and collaborator of Dr. Hoffer. Today, their work is carried on by Dr. William Walsh, their collaborator and intellectual heir, and the author of Nutrient Power. Our daughter has been treated by Drs. trained by him, with great results.

Report comment

GetItRight.

It sounds like you and your family got it right!

This is a link for other readers on how to find an Orthomolecular practitioner;

http://orthomolecular.org/resources/pract.shtml

Best,

Duane

Report comment

Hi Duane,

18 years ago the word encephalopathy first came into my vocabulary and since then I have grown to appreciate knowing that an underlying brain disease is what led me to experience psychosis.

From Wikipedia: “The hallmark of encephalopathy is an altered mental state.”

Providing “talk” therapy alone to someone who is in an altered state of mind because of encephalopathy is not only cruel, but is jeopardizes the health, safety and welfare of the public.

As always, thank you for calling attention to the BMJ’s Best Practice assessment of psychosis protocol.

I only wish a united advocacy agenda would support ensuring patients are provided this standard of care.

Kind Regards,

Maria

https://psychoticdisorders.wordpress.com/2015/03/09/encephalopathy-is-it-the-cause-of-severe-mental-illness/

Encephalopathy /ɛnˌsɛfəˈlɒpəθi/ means disorder or disease of the brain.[1] In modern usage, encephalopathy does not refer to a single disease, but rather to a syndrome of global brain dysfunction; this syndrome can have many different organic and inorganic causes.

Terminology

In some contexts it refers to permanent (or degenerative)[2] brain injury, and in others it is reversible. It can be due to direct injury to the brain, or illness remote from the brain. In medical terms it can refer to a wide variety of brain disorders with very different etiologies, prognoses and implications. For example, prion diseases, all of which cause transmissible spongiform encephalopathies, are invariably fatal, but other encephalopathies are reversible and can have a number of causes including nutritional deficiencies and toxins.

Types

There are many types of encephalopathy. Some examples include:

Mitochondrial encephalopathy: Metabolic disorder caused by dysfunction of mitochondrial DNA. Can affect many body systems, particularly the brain and nervous system.

Glycine encephalopathy: A genetic metabolic disorder involving excess production of glycine

Hepatic encephalopathy: Arising from advanced cirrhosis of the liver

Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy: Permanent or transitory encephalopathy arising from severely reduced oxygen delivery to the brain

Static encephalopathy: Unchanging, or permanent, brain damage

Uremic encephalopathy: Arising from high levels of toxins normally cleared by the kidneys—rare where dialysis is readily available

Wernicke’s encephalopathy: Arising from thiamine deficiency, usually in the setting of alcoholism

Hashimoto’s encephalopathy: Arising from an auto-immune disorder

Hypertensive encephalopathy: Arising from acutely increased blood pressure

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy: Progressive degenerative disease associated with multiple concussions and other forms of head injury

Lyme encephalopathy: Arising from Lyme disease bacteria, including Borrelia burgdorferi.

Toxic encephalopathy: A form of encephalopathy caused by chemicals, often resulting in permanent brain damage

Toxic-Metabolic encephalopathy: A catch-all for brain dysfunction caused by infection, organ failure, or intoxication

Transmissible spongiform encephalopathy: A collection of diseases all caused by prions, and characterized by “spongy” brain tissue (riddled with holes), impaired locomotion or coordination, and a 100% mortality rate. Includes bovine spongiform encephalopathy (mad cow disease), scrapie, and kuru among others.

Neonatal encephalopathy: An obstetric form, often occurring due to lack of oxygen in bloodflow to brain-tissue of the fetus during labour or delivery

Salmonella encephalopathy : A form of encephalopathy caused by food poisoning (especially out of peanuts and rotten meat) often resulting in permanent brain damage and nervous system disorders.

Encephalomyopathy: A combination of encephalopathy and myopathy. Causes may include mitochondrial disease (particularly MELAS) or chronichypophosphatemia, as may occur in cystinosis.[3]

Signs and symptoms

The hallmark of encephalopathy is an altered mental state.

Depending on the type and severity of encephalopathy, common neurological symptoms are loss of cognitive function, subtle personality changes, inability to concentrate, lethargy, and depressed consciousness. Other neurological signs may include myoclonus(involuntary twitching of a muscle or group of muscles), asterixis (abrupt loss of muscle tone, quickly restored),[citation needed] nystagmus (rapid, involuntary eye movement), tremor, seizures, jactitation (restless picking at things characteristic of severe infection),[citation needed] and respiratory abnormalities such as Cheyne-Stokes respiration (cyclic waxing and waning of tidal volume), apneustic respirations and post-hypercapnic apnea..

Diagnosis

Blood tests, cerebrospinal fluid examination by lumbar puncture (also known as spinal tap), brain imaging studies, electroencephalograms and similar diagnostic studies may be used to differentiate the various causes of encephalopathy.

Diagnosis is frequently clinical. That is, no set of tests give the diagnosis, but the entire presentation of the illness with nonspecific test results informs the experienced clinician of the diagnosis.

Therapy

Treatment varies according to the type and severity of the encephalopathy. Anticonvulsants may be prescribed to reduce or halt any seizures. Changes to diet and nutritional supplements may help some patients. In severe cases, dialysis or organ replacement surgery may be needed.

Prognosis

Treating the underlying cause of the disorder may improve or reverse symptoms. However, in some cases, the encephalopathy may cause permanent structural changes and irreversible damage to the brain. These permanent deficits can be considered a form of stable dementia. Some encephalopathies can be fatal.

Report comment

Where are the real doctors? Most haven’t a clue!

We have no protocols in place for a step-by-step assessment to find and treat these *very real* medical conditions!

Talk therapy is not always the answer!

Duane

Report comment

Maria,

Thank you for sharing your personal story and your *wealth* of information!

Duane

Report comment

Unfortunately, my wealth doesn’t seem to do much good.

For the past 4 years I have engaged in a lot of community volunteerism supported by my part time employer.

It has been a great way to connect with our local community through schools, nonprofits, hospitals, universities, law enforcement, politicians, government agencies and attend lectures/events/public forums.

In addition to feeling good about contributing to our community, I am able get the “inside scoop” on the true impact main stream psychiatry and their Medication Management Monopoly has on so many aspects of our society as a whole.

A few month ago I heard Congressman Tim Murphy speak as a guest at one of our public forums and I recently saw Kevin Miller at the Adlerian Society’s Annual Conference .

While I do know of many wonderful stories and I see very small glimpses of hope here and there, in reality, this is a loosing battle.

If I had to come up with an analogy I would say,

imagine an Olympic-size swimming pool

to measure the collective impact on our society that every person involved in the anti-psychiatry movement, the survivors movement, the alternatives movement, CCHR, PsychRights, ISEPP, ICSPP, MIA, etc., etc., has had, imagine we have been filling our Olympic-size swimming pool using whatever tool we have available, whether it is an eye dropper, or a 5 gallon bucket, everyone has been filling the same pool using the same source of water

the pool is looking pretty full and we all feel very hopeful that soon the tables will turn, the scale will tip, the paradigm will shift

now, imagine going down to Miami beach and take a good, long look at that vast ocean and realize

this is our source of water

can you see the difference we made?

Psychiatry will always have the upper hand

What makes this a loosing battle is the fact parents of children labeled with “severe mental illness” are buying into

“the idea that serious mental illness can be a terminal illness, and that this battle wasn’t winnable in the first place,”

http://www.peteearley.com/2015/01/20/zac-pogliano-dies-sleep-mother-son-spoke-frankly-struggles/

http://www.peteearley.com/2015/03/06/god-winks-a-baltimore-police-officers-loving-gift/

I have the privileged to get to know parents who will never give up on their children battling cancer, everyday they fight and miracles beyond belief do happen

In general, our society just gives up on those labeled with “severe mental illness”

Along with our lawmakers, they put all of their faith and hope in psychiatry

For many, mental illness = job security

so it is a loosing battle

I should really just spend my time at the gym and forget about trying to educate others on the causes of “severe mental illness”

Peace-out, Maria

Report comment

Maria,

Take care of yourself. Let the battle go for now. You’ll know when/if you’re meant to come back.

Duane

Report comment

Hi Duane, I like the approach of the Peaceful Warrior

my personal battle ended a long time ago and I feel at peace knowing that I have put out as much information I can to the people with the power to inform others

it just makes it impossible to watch the news, hear tragedy after tragedy, know the “paradigm shift” is taking the slow boat to China and not feel heartbroken, so every now and then I try to post a comment on this site

I know I’m wasting my time, you are right, I should just let it go but in the work environments I’ve been in, we don’t waste time, we fix things that are broken right away, that is how we stay profitable, how can so many be ok with profiting off of the suffering of others????

I just can not comprehend it

I think I will go eat some cake, maybe that is the answer after all

Report comment

That is a good point but on a different topic which is: “mind and body” problem. While this distinction is of course a gross simplification it makes sense in terms of thinking about “mental illness”. In my view there are essentially two options (not mutually exclusive):

– someone has a real organic problem causing cognitive and emotional dysregulation (encephalopathy would be one or them, otehr may include brain tumours or vitamin/microelement deficiencies etc.)

– someone suffers from psychological problems which are not in fact disease but understandable, though in some cases perceived as extreme, reactions to life circumstances both past and present

These are two different scenarios and of course anyone who presents with “symptoms” should be evaluated for physical health and if a problem is identified – sent to an appropriate doctor, be it neurologist, dietician, someone specializing in infectious disease, etc.

Sadly that never happens when someone is presumed to be “mentally ill”. What happens is one is considered a mental case when physical illness are no longer diagnosed (“it’s all in your head”) and psychological problems are treated as if they were medical in nature leading in most cases to worsening of both physical and so-called mental health.

One case that illustrates you’re point very well happened a few weeks back in Poland: a girl was taken to hospital by her parents because of a myriad of physical symptoms, including major headache and some “psychiatric symptoms”. Instead of being properly diagnosed she was shipped to psychiatry where she received “standard care” – she was tied to the bed and left in restraints overnight while her parents were kicked out of the building. Sadly, in the morning she was found dead – autopsy revealed ammonia poisoning in blood which is totally treatable with dialysis. If she was properly diagnosed and treated she’s be alive today.

Report comment

This is tragic.

Report comment

Disease-model, eugenic, thinking is a direct threat to me personally, especially given the recent rise of UKIP and other far-right parties in Europe.

I don’t really know much specifically about UKIP or other far right parties in Europe but I highly doubt that any of them would have reintroducing racist eugenic policies as part of their agenda.

This really sounds like fear mongering on your part. Conflating ‘right wing’, anti-immigration, etc with nazi eugenics is surely wishful thinking.

Report comment

“Conflating ‘right wing’, anti-immigration, etc with nazi eugenics is surely wishful thinking.”

No, not really. These parties always claim they are perfectly reasonable until you find out their leaders partying dressed in Nazi uniforms, taking Hitler-style photos, greeting their buddies with Heil Hitler… I happen to live in East Germany now and the picture isn’t pretty.

Report comment

B,

The “right wing” of a dictatorship is quite different than the right wing of a democracy or constitutional republic. In both cases, the party wants to conserve something it holds valuable.

Tyranny, in the first case. Peace, prosperity, freedom in the latter.

Totalitarianism can come from the “left,” and often does. Stalin, Mao, et al.

We could go on and on, and derail another blog post (once again). But I’ll pass. These debates become like little sound bytes, and are never really debated to the full extent they deserve. And asking others to please take them to the Forum section brings the charge of being a “censor.”

I expressed my point, and I’m out.

Duane

Report comment

Peter I think medicine is only just beginning to understand the complexties of relationship between gene and environment. Sure you inherit some general psychological or behavioural traits, but Epigenetics would have it that genes will only get switched on in certain environments. Similarly they can be switched off again. The traffic is never one way eg from gene to outward manifestation. Work is going on right now showing how mediatation, positive thinking, therapy etc. can all have effects at the genetic level. In the field of autoimmunity, while you might have a genetetic tendency for an HLA type eg. for psoriasis, it is becoming increasingly clear that just changing your diet and lifestyle can have massive effects on your disease. This operates at a genetic level as much as any other level. The role of your microbiome in all of this, and all their genetic material, adds a layer of complexity that simple reductionist models can never understand.

Report comment

Hi,

I think the main ‘problem’ is anxiety; and that there are very good psychological solutions for this.

I think ‘schizophrenia’ as an illness doesn’t exist, and that the symptoms could be found in anyone.

So maybe I’m a bit reductionist.

Report comment

I think I wanted to say even if you think its genetic, it doesn’t mean very much anyway, and our understanding of this stuff is very poor and limited by the typical reductionist way of looking at the world

Re: Gut bacteria and genes: e.g. http://coolinginflammation.blogspot.fi/

Report comment

That’s for sure!

I think it might have been E Fuller Torrey who said the Irish were particularly ‘afflicted’, but Ireland was an easy place to get locked up in (for nothing); or maybe for things besides madness or crime.

Report comment

Maybe they ate the wrong food in Ireland 😉

Report comment

I’m nearly sure he said that as well, that it was the potatoes!

Report comment

My medical records state that the proof I was “bipolar” was that my thoughts were “circumstantial, if not tangential.” The neurologist wanted to discuss a list of lies and gossip he’d gotten from a therapist, who had gotten her information on me from the people who’d abused my child, according to medical records I now have.

I wanted to work on overcoming my denial of the child abuse so I could help my child, not discuss lies and gossip from the child molesters – which would explain why the neurologist and I were having miscommunication problems – we wanted to discuss different things. But I had no idea that the psychological and psychiatric professions were nothing more than gossip masquerading as medicine, so they could aid and abet in keeping child molesters on the streets, at the time.

The patients deserve better.

I had no family or personal history of mental illnesses at the time, the only remotely related family history was a grandmother who was prophetic, she knew when people were going to die. My psychiatric practitioners defamed my grandmother in my medical records and claimed her psychic abilities were psychosis. My grandmother was never psychotic, except possible when on the Stelazine. I don’t respect people who defame other human being’s grandmothers. My grandmother had briefly been put on the old neuroleptic, Stelazine, and was quickly taken off it because she was violently allergic to it. She was never stigmatized or put on any other psych drugs, and lived happily to the ripe old age of 94.

I had switched to this neurologist because a psychiatrist had put me on .5 mg of Risperdal, which resulted in a confessed “Foul up.” This child’s dose of Risperdal had made me psychotic within two weeks. “… neuroleptics … may result in … the anticholinergic intoxication syndrome … Central symptoms may include memory loss, disorientation, incoherence, hallucinations, psychosis, delirium, hyperactivity, twitching or jerking movements, stereotypy, and seizures.” This neuroleptic induced syndrome is basically the exact same description as schizophrenia today.

I believe it’s probable that the etiology of most schizophrenia is the central symptoms of neuroleptic induced anticholinergic intoxication syndrome being misdiagnosed as schizophrenia or bipolar.

The neurologist thought the cure of neuroleptic induced anticholinergic intoxication syndrome was to try basically ever single other neuroleptic on me, prior to finally weaning me off this class of drugs that I have a personal and family history of allergic reactions to. It is disgusting this standard of care is considered “appropriate medical care” in our society today.

And now that I’ve been psychiatrically defamed , I agree with you, I don’t want my children being subjected to this insane psychiatric maltreatment, merely because their mother was wrongly stigmatized. Especially since the DSM disorders, including schizophrenia, are all iatrogenic illnesses, not genetic. Our society does need to get rid of all the DSM stigmatizations. A book of insults is not a “bible.”

Report comment

Thank you very much, Dr. Kinderman, for your wise words and insight. The fact that nature (our genetic or epigenetic inheritance) plays a role should not and must not detract from the importance of nurture; just the opposite. Those with inborn vulnerabilities or predispositions need more and better nurturing, not less. But mental illness and developmental disorders also manifest themselves in loving and responsible families. We need to get away from reductionist dogma (“brain diseases”or or “terrible mothers”) of any stripe and focus on providing gentle, effective and non-coercive healing options.

Report comment

Dr. Kinderman,

I enjoyed your article, and appreciate your insights. My previous comments of frustration are directed at our system, and not toward you. Thank you for being part of MIA.

Duane

Report comment

I wonder if people ever read the criticism of their work?

Here’s a criticism of some of Dr. Kinderman’s work: http://debunkingdenialism.com/2014/11/23/scientific-american-publishes-anti-psychiatry-nonsense/

The author also states, “I just discovered that Peter Kinderman is a writer at the anti-psychiatry website Mad In American (sic), after the book by the same name by Robert Whitaker, a household name among critics of anti-psychiatry.”

Report comment

The arguments he puts forward are simply idiotic. Starting with the “strawman” of chemical imbalance. Psychiatry, hand in hand with pharma, has pushed this bs for decades now and all of a sudden we have misunderstood them and created a strawman? Spare me.

He constantly goes and replaces psychiatry with immunology as if that was a valid argument. Sure I can also replace it with “astrology” and make the claim that since it fits well it must be true. His main point seems to be the typical psychiatric whining “people don’t treat as like real medicine”. Maybe because you’re not real medicine?

He also compares the “genetic” psychiatric illness to genetic phenylketonuria which is ridiculous. If he wanted to make a sensible comparison he should go with type II diabetes for instance, which is as “genetic” as anything. Simply stating the trivial fact that we are biological creatures so everything has some link to our genetic make-up is meaningless in terms of disease.

I could go on but I don’t really have time and interest in dissecting this remarkable piece of ill-logic.

Report comment

I read blogs like that to have a balanced approach towards the subject at hand and not get swayed by extremes on either side.

However, the guy does spout some bullshit. For example, in his article debunkingdenialism.com/2013/11/16/scientific-reality-versus-anti-psychiatry-once-more-unto-the-breach , he writes in the comments : ” Scientology and the anti-psychiatry movement in the U. S. share close historical roots. L. Ron Hubbard was a staunch opponent of psychiatry and Thomas Szasz, retrospectively deserving the title as the founder of anti-psychiatry (although he never used the term and did not consider himself anti-psychiatry), was a scientologist. ”

Is he calling Szasz a scientologist? Perhaps it’s a mistake. If not, he’s ignorant about that little detail, or a liar.

Szasz in an abc interview clearly stated: “Well I got affiliated with an organisation long after I was established as a critic of psychiatry, called Citizens Commission for Human Rights, because they were then the only organisation and they still are the only organisation who had money and had some access to lawyers and were active in trying to free mental patients who were incarcerated in mental hospitals with whom there was nothing wrong, who had committed no crimes, who wanted to get out of the hospital. And that to me was a very worthwhile cause; it’s still a very worthwhile cause. I no more believe in their religion or their beliefs than I believe in the beliefs of any other religion. I am an atheist, I don’t believe in Christianity, in Judaism, in Islam, in Buddhism and I don’t believe in Scientology. I have nothing to do with Scientology.”

Report comment

I haven’t been able to read this through, but is there any mention of the role of early attachment in creating resiliency? If not, then there is no real understanding of psychology or mental health.

Our culture has been obsessed with genetics both where psychology and physical health are concerned. In both areas, the role and power of genetics has been vastly overstated and over bought-into, in psychology probably more so. We utterly neglect and are ignorant of the many key environmental ingredients that go into creating personality and mental health or ill-health, and the (esp. early) psychological environment’s impact on physical health down the line.

Genetics is a holy grail in today’s psychological and medical fields, but after decades and decades and millions of dollars worth of research, it has been leading us (esp. re: psychology and also but less so in medicine) mostly nowhere.

c.f. –John Horgan’s “gene whiz” articles in Scientific American

–Publications by Jay Joseph, PsyD

–“When the Body Says No: Exploring the Stress-Disease Connection” by Gabor Mate, MD (“The war on cancer, for all its triumphs, has generally been a failure because it looks for the causes of malignancy in minute cellular mechanisms. As an astute observer has pointed out, attempting to find the cause of cancer on the cellular level is like trying to understand a traffic jam by examining the internal combustion engine.”)

–“The Manual: The Definitive Book on Parenting and The Causal Theory” by Faye Snyder, PsyD –> Explains the exact environmental mechanisms (children’s social and emotional needs which are either met or not by their parents) which go into creating mental health vs. ill-health, healthy personalities vs. all the personality disorders.

Our society needs to become educated in *real* psychology and stop *assuming* genetic causation for which there is generally no real evidence anyway. Come on, people. The causes are right before our eyes. We just have to have the eyes and the knowledge to see them.

Report comment

James C. Coyne wrote: “Readers are encouraged to retrieve Kinderman’s blog post and see for themselves. It is posted at the anti-psychiatry blog, Mad in America.”

Re: I understand “anti/pro+X/Y/Z” labels (e.g., “anti-psychiatry”, “anti-industry”, “pro-academy”, “anti-depressants”, etc) as bad arguments.

“Pro/anti-psychiatry” – The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy and Psychiatry

https://books.google.com.co/books?id=XzlpAgAAQBAJ&dq=%22pro-psychiatry%22&source=gbs_navlinks_s

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/psychiatry/

When a fan of Peter Gøtzsche criticises Peter Gøtzsche http://chaoticpharmacology.com/2015/10/01/cuando-un-fan-de-peter-gotzsche-critica-a-peter-gotzsche/ (by Marc Casañas, article in Spanish, translation in progress).

http://www.madinamerica.com/2015/09/10-of-the-worst-political-abuses-of-the-psychiatric-and-psychological-professions-in-american-history/

(translation English to Spanish in progress)

http://www.breggin.com/psychiatrysrole.pbreggin.1993.pdf

Report comment