[Editor’s note: The author has chosen to remain anonymous because they are currently in the midst of psychiatric drug/benzo withdrawal and wish to wait until they’re healed before they make the decision about whether or not to emerge publicly with their real name.]

Language is important. And when language dictates specific treatment protocols, it should be used with extreme scrutiny. Using the wrong words can put vulnerable people at risk—not only to their sense of self-worth, their sense of self-knowledge, and they way they are treated, but also to their health.

The psychiatric profession and the pharmaceutical industry have a long history of romanticizing language. When the word “withdrawal” was thought to evoke negative feelings in relation to psychiatric drugs, psychiatry and pharma euphemistically substituted the term “discontinuation syndrome” to lower any apprehensions in patients about taking them (or perhaps they meant “discontinuation” in the global sense—as in “discontinue your life,” “discontinue functioning,” “discontinue brain use”). When Valium got a bad rap under the label “tranquilizer,” the term “anxiolytics” was introduced to describe a newer crop of benzodiazepine tranquilizers—Xanax, Ativan, Klonopin, etc—that were more potent but carried smaller dosage labels, deceiving patients into thinking that they were taking a minimal amount when they were actually taking a dose as much as 20 times more potent than an equivalent dose of Valium (1mg of clonazepam, or Klonopin, for example, is equivalent to approximately 20mg of diazepam, or Valium).

Anyone who has been made iatrogenically dependent on benzodiazepines without informed consent knows the feeling of deception by a formerly trusted practitioner, not to mention how devastating it is to discover that one cannot stop the drug without tapering very slowly, sometimes over years’ duration, to avoid suffering severe and disabling symptoms.

Add to that the experience of being labeled and treated as an “addict,” or as someone who has a “substance use disorder”—sometimes by the very people who did this to you—and the blow is even more bitter, while the outcomes can be dire. People who blindly follow an ignorant clinician’s advice and treat their benzodiazepine dependency like an addiction—by rapidly tapering or admitting themselves to a facility for detox—may find themselves in an incapacitating and even life-threatening situation that can persist for years.

Appealing for the proper use of terminology here—“dependence” instead of “addiction”—is in no way calling for addicts to be stigmatized or treated poorly or for people who are made iatrogenically dependent to be treated superior. Instead, it’s calling for a clear distinction between the two terms that is already made (if not always understood or followed) in most respected specialties of medicine, ensuring that individuals who have iatrogenic physical dependence are treated appropriately. In the case of benzodiazepine dependence, mistreatment—treating it the way one would treat an addiction—can result in potentially fatal seizures, psychosis, or suicide as well as years of infirmity due to protracted withdrawal syndromes. The stakes of using the appropriate terminology in this case couldn’t be higher: in medicine, diagnosis terminology defines protocol and treatment and therefore ultimately determines the outcome for the patient.

A WAR OF WORDS: THE DSM AND DEPENDENCE

Frequently referred to as the DSM, or “psychiatry’s bible,” the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders by the American Psychiatric Association provides criteria to be used by clinicians as they evaluate and diagnose various so-called mental health conditions. The current version, the DSM-5, includes a new chapter on “Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders” that focuses on “substance-use disorders” (SUDs) and “substance-induced disorders,” offering revised criteria for categorizing a variety of disorders and suggesting a range of severity within each diagnostic category.

Before exploring the current DSM-5 terminology, however, let’s go back and look at the previous edition, the DSM-IV, because the terminology used in that version continues to cause confusion. The DSM-IV divided substance-use disorders into two types: “substance abuse” and “substance dependence.” At a glance this terminology may seem appropriate—one might assume that “substance abuse” refers to the abuse of a drug and “substance dependence” refers to mere physical dependence (in medicine,“dependence” is typically used to describe the body’s adaptation to a consumed substance without necessarily implying abusive behavior). But that’s not what the terminology meant in the DSM-IV. In the DSM-IV, the label “substance abuse” was used to describe an earlier or less-severe form of addiction, while “substance dependence” was given to a more-severe manifestation of the disorder. Baffled yet? Many clinicians certainly were.

The editorial below from the American Journal of Psychiatry sheds some light on the DSM-IV’s choice of terminology. Apparently the committee for the DSM-IV had opted for the term “dependence” in place of the word “addiction” in part because “addiction” was thought by some to sound pejorative. The authors of this editorial, arguing for revised terminology, point out that the term “dependence” as used in the DSM-IV only served to confuse clinicians, with the result that patients suffered:

There was good agreement among [DSM-IV] committee members as to the definition of addiction, but there was disagreement as to the label that should be used. The proponents of the term “addiction” believed that this word would convey the appropriate meaning of the compulsive drug-taking condition and would distinguish it from “physical” dependence,” which is normal and can occur in anyone who takes medications that affect the CNS. Those who favored the term “dependence” felt that this was a more neutral term that could easily apply to all drugs, including alcohol and nicotine. The committee members argued that the word “addiction’” was a pejorative term that would add to the stigmatization of people with substance use disorders. A vote was taken at one of the last meetings of the committee, and the word “dependence” won over “addiction” by a single vote.

The term “dependence” has traditionally been used to describe “physical dependence,” which refers to the adaptations that result in withdrawal symptoms when drugs . . . are discontinued. Physical dependence is also observed with certain psychoactive medications, such as antidepressants and beta-blockers. However, the adaptations associated with drug withdrawal are distinct from the adaptations that result in addiction, which refers to the loss of control over the intense urges to take the drug even at the expense of adverse consequences. For example, research has shown that when opiates are administered to a naive animal, adaptation begins to occur after the first dose so that the second dose has a discernibly decreased effect from the first. After several days of taking the medication, abrupt cessation produces a withdrawal syndrome varying with the duration of treatment and the dose level. This is an expected pharmacological response, and although it may occur among addicts, it is quite distinct from compulsive drug-seeking behavior. This has resulted in confusion among clinicians regarding the difference between “dependence” in a DSM sense, which is really “addiction,” and “dependence” as a normal physiological adaptation to repeated dosing of a medication. The result is that clinicians who see evidence of tolerance and withdrawal symptoms assume that this means addiction, and patients requiring additional pain medication are made to suffer. Similarly, pain patients in need of opiate medications may forgo proper treatment because of the fear of dependence, which is self-limiting by equating it with addiction. . . .

In the case of substance use disorders, the medical world drastically needs a change in labeling. Addiction is a perfectly acceptable word. It is used by the American Society of Addiction Medicine, the American Association of Addiction Psychiatrists, the American Journal on Addictions, and the oldest journal in the field, simply known as Addiction. It is clear that any harm that might occur because of the pejorative connotation of the word “addiction” would be completely outweighed by the tremendous harm that is now being done to the patients who have had needed medication withheld because their doctors believe that they are addicted simply because they are dependent.

And so, it was decided to merge the DSM-IV’s terminology of “substance abuse” and “substance dependence” into one entity called “substance-use disorders” (SUD) in the DSM-5.

In outlining their revisions to the DSM-5, the American Psychiatric Association did issue a clarification acknowledging that addiction and physical dependence are not synonymous: “The diagnosis of dependence caused much confusion. Most people link dependence with ‘addiction’ when in fact dependence can be a normal body response to a substance.” But their clarification does little good if medical providers remain addled by the previous DSM-IV terminology and are unable to differentiate addiction/abuse from iatrogenic dependence. Such lingering confusion could lead to people being wrongly diagnosed and treated under the diagnosis of “substance abuse disorder” (SUD) when they are merely physically dependent. The reason this is inevitable is because there is no separate and distinct diagnosis for iatrogenic physical dependence alone.

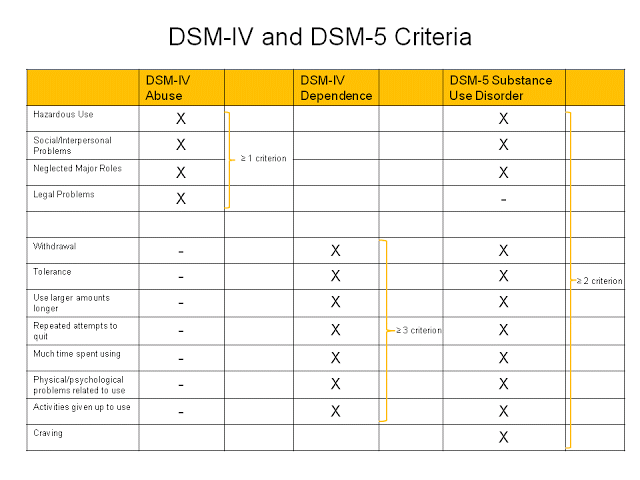

The following image shows a comparison between the diagnostic criteria used in the DSM-IV and the DSM-5: (Image Source)

In practice, patients who present with tolerance and withdrawal only, even though they meet two of the symptom criteria above, are not meant to be diagnosed as having “SUD-Mild” if they are taking the drug under medical supervision.

Since there is no separate or distinct diagnosis for this condition, patients may still find themselves misdiagnosed with SUD (addiction) according to the DSM-5 criteria. For example, interdose withdrawal—withdrawal between doses due to a drug’s short half-life—might be mistaken for “craving.” And if you look at the criteria for therapeutic dose dependence in The Ashton Manual, many patients who are iatrogenically dependent could easily meet the “repeated attempts to quit” criterion if, say, their attempts to quit cold-turkey, or to taper too quickly, produce intolerable withdrawal symptoms. As for “using larger amounts,” many people prescribed a benzo end up having their dose increased over time by their prescriber due to tolerance, while “physical/psychological problems related to use” are seen with tolerance as well, even when a benzo is used only as a doctor prescribes.

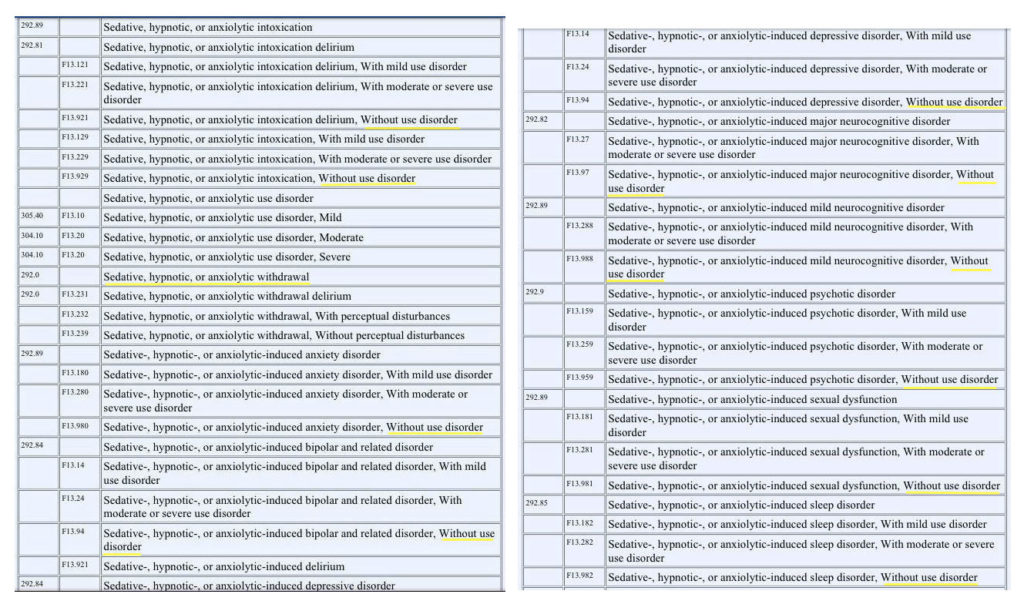

So what should people who present with only tolerance and withdrawal (after taking a prescribed benzo) be diagnosed with, according to the DSM-5? Are there really no options for diagnosing iatrogenic benzodiazepine dependence that don’t include substance-use criteria? Take a look at the image below, which is a listing of all available DSM-5 diagnoses with corresponding ICD codes for sedative, hypnotic, anxiolytic use:

Underlined in yellow are the substance-induced disorders, indicating a number of “disorders” that are not accompanied by a “use disorder” (that is, a substance-use disorder). These include withdrawal as well as intoxication and other substance/medication-induced “mental disorders” (e.g., sleep disorders, neurocognitive disorders, sexual dysfunction, anxiety disorder, or depressive disorder). Would any of those fit the bill?

Let’s think this through. Any psychopharmaceutical intervention with benzodiazepines that lasts more than the recommended two to four weeks, resulting in dependence, tolerance, withdrawal, or toxicity, seems to become a self-fulfilling prophecy. In other words, if people take benzos long-term as directed and go on to inevitably develop physical dependence, which then causes symptoms such as neurocognitive dysfunction or depression, they could wind up with a “substance-induced” disorder diagnosis on top of the diagnosis that led them to be prescribed a benzo to begin with. That means that even if a person’s initial diagnosis was a purely physical condition (such as muscle spasms), that person could still wind up with a “disorder” label (i.e., a substance-induced disorder) according to the DSM-5 criteria. So if people don’t have a “disorder” or psychiatric label prior to taking the drugs, they most certainly can after (despite physical dependence being an expected, normal physiological response). How convenient a trap for psychiatry to set.

If this all seems hopelessly convoluted, it’s because it is. The lack of clear terminology to describe iatrogenic dependence and withdrawal related to benzos can have outcomes that are devastating for the patient. There is no way around it: we need to start using unambiguous and universal terminology that is accepted by all medical specialties and make a distinction between physical dependence and addiction once and for all.

Exactly why is clear and universal language so important? Because the standard protocol and treatment for SUD/addiction/abuse can be devastating for someone with iatrogenic benzodiazepine dependence—a detoxification program, cold-turkey withdrawal, a rapid taper, and/or attendance at a 12-step program to address the behavior of addiction. We know from The Ashton Manual, written by Dr. Heather Ashton, the world’s leading expert on benzodiazepines, that it is crucial that withdrawal from benzodiazepines not be treated in the same way as addiction:

There is absolutely no doubt that anyone withdrawing from long-term benzodiazepines must reduce the dosage slowly. Abrupt or over-rapid withdrawal, especially from high dosage, can give rise to severe symptoms (convulsions, psychotic reactions, acute anxiety states) and may increase the risk of protracted withdrawal symptoms. Detoxification centres which also deal with alcohol and illegal drugs are not appropriate for prescribed benzodiazepine users. Such clinics tend to withdraw patients too rapidly, apply rigid rules and “contract” methods, and provide inadequate support or follow-up.

Similarly, a consensus statement released by The American Society of Addiction Medicine, The American Academy of Pain Medicine and the American Pain Society states: “When drugs that induce physical dependence are no longer needed, they should be carefully tapered while monitoring clinical symptoms to avoid withdrawal phenomena…Such tapering, or withdrawal, of medication should not be termed detoxification.”

Given that the DSM-5 doesn’t have a category for iatrogenic withdrawal syndrome related to benzos, it’s not surprising that it also doesn’t acknowledge the existence of protracted withdrawal syndrome—a severe form of withdrawal that can cause symptoms that continue as long as several years after a benzo is out of the body. But this lack is troubling, because enlightened medical experts (and many victims) feel that referring to this condition as “withdrawal” or “withdrawal syndrome” does not accurately describe the enormous long-term damage involved, nor does it suggest the extremely slow tapering protocol that is necessary for preventing it. It also fosters the misconception that withdrawal is the result of addiction, or that it should resolve over the course of weeks.

It is precisely this confusion that Dr. Stuart Shipko notes regarding the language used to describe a related syndrome resulting from the discontinuation of SSRIs. He writes:

Protracted withdrawal needs a better name. The term “protracted withdrawal” does describe the time sequence of symptoms after stopping serotonin based antidepressants, but is a poor choice of language when discussing this with your doctor. Medicine does not recognize such a thing as protracted withdrawal. Withdrawal is considered something that goes away within days or weeks of stopping a drug. If you are going to talk to your doctor about these sorts of problems, then it is best to describe the problem as symptoms that happened after stopping the drugs. I realize that many physicians will declare these new symptoms the start of a new mental illness—usually bipolar—but calling it protracted withdrawal just confuses the doctor…I refer to protracted withdrawal as drug neurotoxicity.

It seems that a similar argument could—and should—be made for iatrogenic benzodiazepine cessation. Perhaps incorporating a new moniker such as “drug neurotoxicity” would help in the goal of making crucial distinctions and give this condition the universal platform that is so desperately needed.

COMING TO TERMS: THE DEFINITIONS

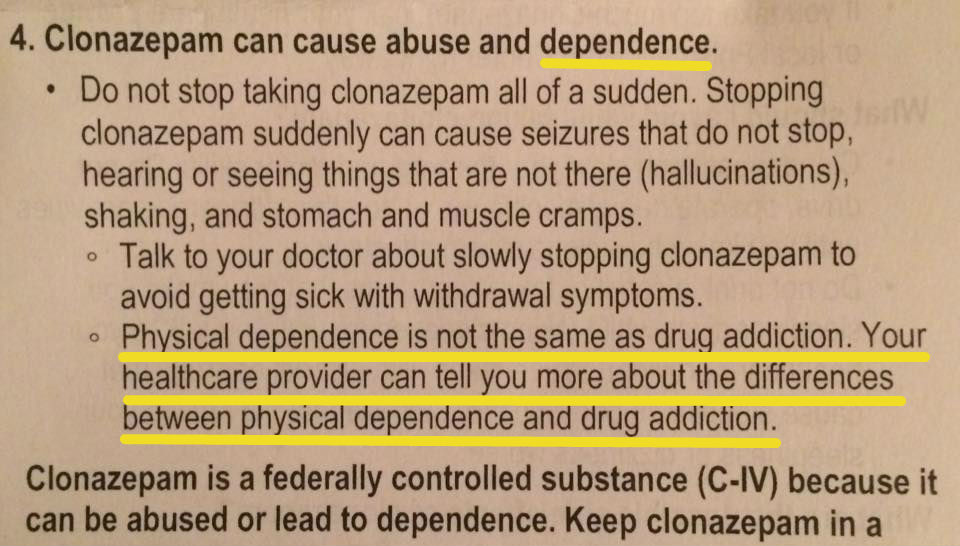

An acquaintance who is iatrogenically dependent on the benzo Klonopin and is in the process of tapering recently shared the text below, included in a new leaflet attached to her prescription:

“Your healthcare provider can tell you more about the differences between physical dependence and drug addiction,” it states. Is that so? If you asked most people who have been iatrogenically dependent on a benzo, now or in the past, you would likely discover just how far behind the medical community is when it comes to discerning between the two. The fact is, if benzo dependence were diagnosed correctly and patients treated accordingly, there would not be any presenting cases of cold-turkey withdrawal. Yet, sadly, at alarming rates, rehabs and detox centers are essentially cold-turkeying unsuspecting people who are desperate to be free of these drugs and charging significant sums of money—only to send people home sick and indigent to face what may be years of suffering in protracted withdrawal syndromes.

As for those people who do not resort to rehab or detox centers, they are constantly scrambling and struggling to find medical providers who are understanding and educated or at least “benzo-cooperative” and willing to prescribe the drug in a way that allows for a slow, controlled taper (even if the providers know little about benzo withdrawal themselves). There is so little understanding in the medical community about iatrogenic benzo dependence that some patients simply cannot find a prescriber to work with them this way and end up having their prescription cut off by someone who (for whatever reason) feels they should get off the drug sooner.

So when people find themselves caught in this cobweb of iatrogenic benzodiazepine dependence it feels like this: The medical community renders you dependent on these drugs, most often without informed consent or fair warning about their potential for dependence and severe withdrawal. You take the prescription compliantly as directed by your medical provider. Then, once you experience tolerance symptoms or become dependent and are facing withdrawal, your medical provider either turns his or her back on you—in some cases treating you like a drug-seeking addict and refusing to provide the repeat prescriptions you need for a slow and controlled (by you) reduction plan—or else your provider has no clue how to manage benzodiazepine withdrawal at all.

Consider the first two steps in The Ashton Manual—the most respected guide on benzos—under “Before Starting Benzodiazepine Withdrawal”: 1. Consult your doctor or pharmacist and 2. Make sure you have adequate psychological support. Perhaps those initial two steps are more easily achieved in the U.K., where Dr. Ashton is based, but in the U.S., the first step can be impossible, for all the reasons given above, and the second is made extremely difficult when family, friends, doctors, therapists, and much of society considers you an addict or drug abuser and discriminates against you, treats you poorly, or makes statements like “you just need to stop using the drugs.” An overwhelming number of iatrogenically benzo-dependent people are shunned or abandoned by friends and family who might otherwise help and support them through withdrawal if they only understood that dependence is a result of negligence on the part of the medical profession and not a result of abusing the drugs.

A consensus statement released by The American Academy of Pain Medicine, the American Pain Society, and the American Society of Addiction Medicine sought to define the terminology and recommended their definitions for use. The definitions presented in the consensus Statement are as follows:

Addiction:

Addiction is a primary, chronic, neurobiological disease, with genetic, psychosocial, and environmental factors influencing its development and manifestations. It is characterized by behaviors that include one or more of the following: impaired control over drug use, compulsive use, continued use despite harm, and craving.

Physical Dependence:

Physical dependence is a state of adaptation that is manifested by a drug class specific withdrawal syndrome that can be produced by abrupt cessation, rapid dose reduction, decreasing blood level of the drug, and/or administration of an antagonist.

Tolerance:

Tolerance is a state of adaptation in which exposure to a drug induces changes that result in a diminution of one or more of the drug’s effects over time.

The consensus statement goes on to explain the reasoning for defining the terms:

Physical dependence, tolerance and addiction are discrete and different phenomena that are often confused. Since their clinical implications and management differ markedly, it is important that uniform definitions, based on current scientific and clinical understanding, be established in order to promote better care of patients…

Clear terminology is necessary for effective communication regarding medical issues. Scientists, clinicians, regulators and the lay public use disparate definitions of terms related to addiction. These disparities contribute to a misunderstanding of the nature of addiction and the risk of addiction. Confusion…results in unnecessary suffering, economic burdens to society, and inappropriate adverse actions against patients and professionals.

In countries such as the U.K., where there is universal healthcare, uniform definitions and treatment protocols for benzodiazepine dependence are available for all specialities to reference and follow in the British National Formulary. Yet even in the U.K., many advocates still refer to the benzodiazepine epidemic using addiction terminology, albeit putting the word “involuntary” or “accidental” before “addiction” (which might imply that the person was rendered iatrogenically dependent and then, at some point, began abusing the drugs). In the U.S., where healthcare bodies and regulations operate with less coordination, there are even more inefficiencies when it comes to uniformity, contributing further to the problem.

The simple fact is that much confusion could be resolved if medical professionals would actually listen to what their patients are telling them, much in the same way Dr. Ashton was attentive to the patients she encountered in her clinic. As described by her in The Ashton Manual:

For twelve years (1982-1994) I ran a Benzodiazepine Withdrawal Clinic for people wanting to come off their tranquillisers and sleeping pills. Much of what I know about this subject was taught to me by those brave and long-suffering men and women. By listening to the histories of over 300 “patients” and by closely following their progress (week-by-week and sometimes day-by-day), I gradually learned what long-term benzodiazepine use and subsequent withdrawal entails. Most of the people attending the clinic had been taking benzodiazepines prescribed by their doctors for many years, sometimes over 20 years. They wished to stop because they did not feel well. They realized that the drugs, though effective when first prescribed, might now be actually making them feel ill…It is interesting that the patients themselves, and not the medical profession, were the first to realize that long-term use of benzodiazepines can cause problems.

ALONG SIMILAR LINES: DEPENDENCE AND OTHER DRUGS

To understand how ridiculous is it to lump individuals who’ve been made physically dependent on a substance with those who have substance abuse, addiction, or substance use disorder (SUD), consider that it is widely recognized in the medical literature that physical dependence can develop with the chronic use of many classes of medications. These include beta blockers, alpha-2 adrenergic agents, corticosteroids, proton pump inhibitors, antidepressants, and other drugs that are not associated with addictive disorders. One would be hard-pressed to find, say, a cardiologist who would prescribe a hypertensive patient long-term beta-blocker therapy, then diagnose that patient with “addiction” or “SUD” simply because the individual developed tolerance, dependence, and/or withdrawal symptoms when attempting to stop the drug. Equally preposterous would be the idea of sending that patient to a rehab or detox program to deal with his or her “beta blocker addiction,” only to be cold-turkeyed and sent home in a state of beta-blocker withdrawal, a syndrome of sympathetic overactivity that can include agitation, headache, sweating, and nausea as well as rapid upswings in blood pressure or exacerbation of cardiac disease.

Some clinicians (but not nearly enough) are now aware that antidepressants can also cause physical dependence and withdrawal syndromes when used as directed over a long term. In fact, SSRI withdrawal syndromes share many of the symptoms that are characteristic of benzodiazepine withdrawal. But here is where the need for accurate terminology comes glaringly into play.

Consider a case in point: one Danish meta-analysis asserts that antidepressants lead to addiction, but the study’s conclusion is met with serious reservations. Among those objecting is Lars Vedel Kessing, clinical professor and attending physician at the Psychiatric Centre Copenhagen, who argues that SSRIs are not addictive. “Before you can categorize something as addictive there has to be an onset of four fundamental symptoms,” he states:

- First, you lose control and the desire to take the drug becomes compulsive. In some sense you could say the drug takes control of you.

- Next is the onset of tolerance.The dosage must be increased all the time to get the desired effect and you keep taking more and more of the drug.

- Directly related to this is the third symptom; a strong urge to privately obtain more of the drug so it can be taken without the physician’s knowledge.

- Lastly, there will be a detrimental effect to the individual who will no longer be able to function socially or physically.

Kessing goes on to say: “Not a single one of these phenomena are present in SSRI discontinuation syndrome, but all four are present in treatments with benzodiazepines.”

Now, let’s go back to the Danish meta-analysis. If its authors had used proper terminology, indicating that both antidepressants and benzodiazepines cause physical dependence that leads to similar withdrawal syndromes, their claim would have been accurate. But because they argue that both classes of drugs are “addictive” and should be classified as such, Kessing makes a counterclaim that is only partially correct. Where Kessing is mistaken is in his final statement that “all four [symptoms] are present in treatments with benzodiazepines.” The fact is—and this distinction could not be more fundamental—all four symptoms are present only in people who abuse or are addicted to benzodiazepines and are not seen in those who are made iatrogenically dependent on the drugs in the same way that SSRI dependence occurs.

This point is made clear in a quote from Dr. Heather Ashton, based on a dozen years spent running a withdrawal clinic to help over three hundred individuals withdraw safely from the benzodiazepines they had been prescribed:

Benzo victims bravely work to return their nervous systems to acceptable function. They must continue to use decreasing dosages of the harmful drug until those nervous systems can run without the GABA agonist. This need is hard for victims to accept. They feel trapped because they must use a poison to safely come off of a poison. They suffer horribly as they work to repair the harm done by a formerly trusted MD. These victims certainly have no cravings or desire to use benzos. When you assume that what is true of addictive-drug patients is true of benzo victims, you have doubly harmed these victims.

Unfortunately, however, Kessing’s opinions are often shared by other misinformed clinicians, leaving people who are physically dependent on benzodiazepines to be thrown to the wolves and in dire need of support as they attempt to discontinue their prescribed drug safely in a slow taper. And while the withdrawal symptoms for benzodiazepines and antidepressants can be very similar, we do not generally see antidepressant-dependent patients being forced into rehab centers, labeled as “Prozac addicts” or “Effexor addicts,” or treated as if they were drug seekers or abusing their drugs. It is safe to say, too, that people who are dependent on SSRIs are unlikely to find themselves searching desperately for an “SSRI-cooperative” physician willing to prescribe them repeat prescriptions of, say, liquid Prozac in order to complete a slow, gradual taper off the drug. The same is sadly not true for vast numbers of people made iatrogenically dependent on benzodiazepines.

Perhaps one reason benzo-dependent individuals encounter so much resistance and misunderstanding from medical professionals, compared to those who are dependent on antidepressants or beta-blockers, is because benzos are classified as schedule IV controlled substances, while SSRIs and beta-blockers are not. A real paradox, then, lies in the fact that the DEA defines schedule IV drugs as “drugs with a low potential for abuse and low risk of dependence.” Anyone who has ever been rendered iatrogenically dependent on benzodiazepines, then tried to reduce their dose, may well respond to the phrase “low risk of dependence” with side-splitting laughter or a shiver of disgust. The fact is that benzodiazepines are so inherently dependence-causing (sometimes in as little as a few weeks) that, for those who experience it, the state of benzo dependency feels as though the drug has deeply penetrated the cytoplasm of one’s neurons and attached to the GABA receptors with the tenacity of a limpet.

Rather than comparing benzodiazepines to beta blockers and SSRIs, then, perhaps a more appropriate comparison would be to opiate narcotics, which are also classified as controlled substances (although, arguably, the withdrawal from benzos can be far more dangerous, painful, and long-lasting). Most (good) pain management specialists recognize that chronic use of opioid analgesics can result in tolerance, dependence, and withdrawal symptoms when discontinued. If, for example, a patient suffers from painful burns resulting from a fire and takes opiates over a long term as prescribed by a pain-management clinician, it would likely be understood that any development of tolerance, dependence, and/or withdrawal symptoms upon cessation of the drug would be an expected pharmacological response and not evidence of “addiction” or “abuse” or “SUD.” It would also be understood that the opiate needs to be tapered slowly after the burns heal and the pain subsides.

From a WebMD article on pain management: “Probably not a week goes by that I don’t hear from a doctor who wants me to see their patient because they think they’re addicted, but really they’re just physically dependent,” says Scott Fishman, MD, professor of anesthesiology and Chief of the Division of Pain Medicine at the University of California Davis School of Medicine. Notes Susan Weiss, PhD, Chief of the Science Policy Branch at the National Institute on Drug Abuse, in the same article: “Physical dependence, which can include tolerance and withdrawal, is different. It’s a part of addiction but it can happen without someone being addicted.” Weiss goes on to say that if people have withdrawal symptoms when they stop taking their pain medication, “it means that they need to be under a doctor’s care to stop taking the drugs, but not necessarily that they’re addicted.” Marvin Seppala, MD, Chief Medical Officer at the Hazelden Foundation, concurs: “The vast majority of people, when prescribed these medications, use them correctly without developing addiction.”

Every one of the quotes in the paragraph above can be applied to iatrogenic benzo dependency. So where are the medical professionals who are advocating for understanding, compassion, and proper care of the patients to whom they themselves have prescribed these drugs?

GETTING ON THE SAME PAGE

When it comes to benzodiazepines, confusion and misunderstanding around terminology, definitions, and classifications is not just a matter of semantics—it has very real implications for human beings whose quality of life is at stake, and who—if their providers get it wrong—face the possibility of years of inhumane suffering in protracted withdrawal syndromes. The medical community cannot have it all ways: they need to get on the same page. Yet in the more than 50 years since benzodiazepines were first introduced, this has yet to occur, and as a result, people who find themselves (through no fault of their own) iatrogenically dependent on benzos are met with one of the following responses, depending on how enlightened their provider may be:

- Patients are told that the drugs are “safe,” “non-habit forming,” or “not addictive” and “don’t cause withdrawal” and that “the symptoms are all in your head” or “from something else,” as benzos are an “effective treatment.”

- Patients are refused a renewed prescription for the benzo, despite being already iatrogenically dependent on it, based on the logic that the drugs are “addictive” or “cause dependence” or “are dangerous.” Of course, this is the very information that should be provided as part of informed consent prior to ever prescribing the drugs—and is a moot point once a patient is already physically dependent and needs a continual supply in order to taper.

- As soon as patients experience withdrawal symptoms upon trying to stop, or from making too large a reduction in dose (usually out of ignorance of their iatrogenic dependence and the need for a slow taper), they are told that their symptoms are evidence of “the return of the underlying condition”—i.e., “mental illness”—and demonstrate the ongoing “need” for the drugs. Of course, this reasoning makes little sense in light of the fact that many people are prescribed benzos for non-psychiatric medical conditions—everything from restless leg syndrome to Lyme disease to facial tics to insomnia—and experience the same withdrawal symptoms (some of which mimic psychiatric disorders) as everyone else.

- Patients are told just the opposite—that their withdrawal symptoms are “evidence of addiction” and that they should stop the drugs right away without tapering, or through a too-rapid taper in a detox facility, leaving them in a state of protracted withdrawal that potentially lasts for years.

- Patients are extremely lucky (and one of the rare few) to encounter a “benzo wise” or “benzo cooperative” practitioner who recognizes and diagnoses iatrogenic dependence and agrees to prescribe the benzo for a slow, controlled (by the patient) taper in order to discontinue safely. (Finding a practitioner who realizes just how slowly some benzo tapers need to be in order to avoid severe withdrawal symptoms would be like finding the Holy Grail.)

I suppose it is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail. But this matters, profoundly, when you are the nail. Being mislabeled as an “addict” when you are not can potentially lead to serious consequences, such as the loss of a license or professional career. Being told that one’s withdrawal symptoms are a sign of a “resurfacing” mental disorder (when they are not) can be equally damaging. And which is it, anyway? Are people who’ve been prescribed benzos (for whatever reason) addicts who need to get off the drug immediately, or are they mental patients who need to stay on the drug for life? Depending on whom you ask, you’re likely to get a multitude of answers—and there lies the problem. There is no consistency among the medical community, and the people who suffer from this lack of clarity are the patients.

The ultimate goal, of course, would be for medical providers to adhere to the recommended 2-4 week (including tapering) prescribing guidelines for benzodiazepines and prevent the problem of benzodiazepine dependence and withdrawal from ever happening. But until that comes to pass, and while countless people have been made dependent and left to navigate the symptoms of tolerance and withdrawal on their own, something fundamental must change. To those who insist on labeling people: at least learn the terminology and apply it correctly, so that people stop suffering at the hands of ignorance. We need to make sure that the uniform definitions of terms such as addiction, dependence, and tolerance are accepted and used by clinicians, regulators, and the public both nationally and internationally, to ensure the appropriate treatment of iatrogenic benzodiazepine dependence throughout the world.

We all know that medical professionals take an oath to do no harm. But in the case of iatrogenic benzodiazepine dependence, patients are harmed, first when prescribers abuse the drugs themselves by prescribing them for longer than their own regulations recommend, without informed consent from the patient about the potential for dependence, tolerance, and horrific withdrawal syndromes with longer use. And patients are harmed twice when the medical profession fails—or refuses—to recognize tolerance, interdose withdrawal, and physical dependence for what they are, but insists instead on misdiagnosing and mistreating these phenomena as “addiction” or the recurrence of “underlying mental illness” when their patients make a good faith effort to stop taking the drug.

Part II of “Don’t Harm Them Twice,” which focuses on suggestions for how to appropriate accurate terminology, will appear in a future edition of Mad in America.

* * * * *

Special thanks to TK, phenomenal editor and benzo comrade, for your time and editing skills on this piece. My cognitively-impaired “benzo brain” could not have brought it to fruition without you. Thanks also to LD, SS, JF, AN, and LM for your input, continual encouragement, and unwavering support.

* * * * *

REFERENCES:

“4.1 Hypnotics and Anxiolytics : British National Formulary.” Benzo.org.uk. 1 Nov. 2013. Web. 4 Sept. 2015. <http://www.benzo.org.uk/BNF.htm>.

Ashton, C H. “Benzodiazepines: How They Work & How to Withdraw.” Benzo.org.uk. 2002. Web. 4 Sept. 2015.

Ashton, C Heather. “History of Benzodiazepines: What the Textbooks May Not Tell You.” Psychiatric Medication Awareness Group. 12 Oct. 2005. Web. 4 Sept. 2015.

Dawson, George. “DSM-IV to DSM-5 Addiction Graphic.” Real Psychiatry Technical Blog. 17 Sept. 2013. Web. 4 Sept. 2015.

“Definitions Related to the Use of Opioids for the Treatment of Pain: Consensus Statement of the American Academy of Pain Medicine, the American Pain Society, and the American Society of Addiction Medicine.” American Society of Addiction Medicine. 2001. Web. 4 Sept. 2015.

“Drug Scheduling.” United States Drug Enforcement Administration. Web. 4 Sept. 2015. <http://www.dea.gov/druginfo/ds.shtml>.

Haslam, Barry. “My Successful Campaign for Dedicated Benzo Withdrawal Services – Mad In America.” Mad In America. 15 Aug. 2015. Web. 4 Sept. 2015.

“Highlights of Changes from DSM-IV-TR to DSM-5.” American Psychiatric Association DSM-5 Development. American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013. Web. 4 Sept. 2015.

Hitti, Miranda. “Prescription Painkiller Addiction: 7 Myths.” WebMD. WebMD, 10 Aug. 2011. Web. 4 Sept. 2015.

“Physical Dependence.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. Web. 4 Sept. 2015.

Secher, Kristian. “Scientist: Antidepressants Cause Addiction.”Sciencenordic.com. 10 May 2013. Web. 4 Sept. 2015.

Shipko, Stuart. “Shooting the Odds, Part III.” Mad In America. 1 Sept. 2015. Web. 4 Sept. 2015.

“Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders.” American Psychiatric Association DSM-5 Development. American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013. Web. 4 Sept. 2015.

Thanks for this article. You have obviously thought carefully for a long time about these issues and amassed a lot of knowledge about benzos and the mental health care systems that manage their use.

At the time that I took Klonopin several years ago, during a period of overwhelming anxiety and terror, I was fortunately aware of its dangerously addictive potential. For that reason I forced myself to stop taking it after only a few months of relatively low doses. It was hell (the fear, not tapering off; I never got strongly attached to Klonopin) and it could have been easier in the short term if I’d taken higher doses and stayed on the drug. But I’m so glad I did not do that. I really benefitted from accurate information about the addictive potential of these drugs early on, something many people don’t get until it is too late and they are already strongly bound to the drug biologically and psychologically.

Report comment

If you respond to this, can you comment in a general sense on why you do not yet feel ready to publicly speak out on these issues? I am in a similar position to you. I am wondering what holds you back… what bad consequences do you imagine work-wise, socially, etc.?

Report comment

Hi bpdtransformation,

Thank you for your comment. I am glad that you were already aware (or made aware) of some of the possible outcomes from the longer-term use of benzos. Remember though, they don’t only have “addictive potential”, they also have dependence potential. I just point that out b/c appropriate language is the whole topic of the article. If you took “small doses” (there really is no “small dose” when it comes to benzos- I’ve met people in the withdrawal communities who became dependent in as little as a few weeks on the smallest available dose and who suffered just the same in severity and duration as people who were on them for 10 years at higher doses) for a short period of time, as directed by your doctor, you weren’t displaying any addictive behaviors and only then at risk for their dependence potential. Part II of the article (to come soon) gets more into this addictive potential vs. dependence potential business and why it’s important to use the right language in order to warn and provide informed consent (stay tuned!).

To answer your question about anonymity, there are a number of reasons. Mainly, due to this iatrogenic benzo nightmare, and subsequent misdiagnosis of both addiction and so-called “mental illness”, I have lost a lot- my ability to work, friends, house, income, etc. I am remaining anonymous (for the time being) to be sure I can resume my career and present my case as to what happened to me from a place of full healing and having nothing that interferes w/ that process going smoothly, as it’s my only chance of getting back on my feet financially. Secondly, I am still suffering from the protracted neurotoxic effects the benzos had on my brain and nervous system and due to the nature of some of the symptoms that come with that (paranoia, mental confusion, cognitive issues, memory issues, etc) , I felt it was better for me to recover completely and make the decision to come forward without anonymity from a place of feeling safe and with full mental clarity and complete healing. I am not ashamed of this at all, and I don’t think anyone who is a victim of iatrogenic injury should be, and feel quite passionately about speaking out about this cause with many plans to in the future- the timing just isn’t right yet, as healing isn’t happening as quickly as I’ve been willing it to. I hope that answered your question.

Report comment

Sure… thanks for your response. I totally understand. I am in a similar position of having returned to society after a MH diagnosis but not wanting people I work with to know for fear of losing employment if some uninformed person thinks it means I can’t do the work… that’s why I had asked.

Report comment

JD

As someone who has worked with people with addictions for over 24 years and has written about and discussed benzodiazepines many times on the MIA blog, I found this article to be very informative and challenging. I certainly have been guilty at times of confusing or misusing the terms ” addiction” with “iatrogenic dependence” when discussing benzos and other prescribed drugs. This blog helps me clearly understand the scientific AND political importance of using these terms correctly; I will try to do better in the future.

One area where these concepts can become blurred and increasingly confusing is when people prescribed benzodiazepines for the long term are also using other sedative hypnotics such as alcohol and/or other drugs classified as opiates. Now we have exponentially greater risk for a “perfect storm” of dependence or (in some cases) addiction that can often lead to death because of cardiac and lung suppression.

Because of the high number of benzo prescriptions in the U.S. (94 million in 2013) many of these drugs end up in the street and in the hands of people with major addictions, especially with opiates. This becomes a highly sought after drug cocktail due to the synergistic expansion of the “high.”

Currently 60% or more of opiate addicted people came to this state of being through negligent prescribing by doctors leading to iatrogenic dependence. This dependence can quickly evolve into full blown addiction and remains one of the primary causes of the opiate epidemic raging in this country, and in other developed countries throughout the world. Perhaps we need to label this as “addiction caused by iatrogenic (or medically induced) dependence.”

We cannot repeat often enough the statistic that at least 30% of all fatalities in opiate overdoses (that are rapidly growing in numbers) involve the use of benzos – benzos are more often the decisive and fatal component in these drug cocktails (see my recent MIA blog titled “Benzodiazepines: Psychiatry’s Weakest Link.”

JD thanks again for this blog, the benzodiazepine crisis and the complicit role of Psychiatry and Big Pharma in this oppressive tragedy needs more exposure, education, and activism. Your blogs will play an important role in this process.

Richard

Report comment

Hi Richard, Thank you for your comment. Thank you too for putting thought into care with language. As someone who has worked with people with addictions, it’s important that the addiction/rehab/detox community can discern between addiction and dependence so as not to misdiagnose, harm and further traumatize people who are merely iatrogenically physically dependent.

I did read your last blog and while yes, *some* people are put on opiates and start to develop addictive behaviors and abuse the drugs and take other drugs (sometimes benzos, alcohol, etc) in combination with them looking for a “high” or go on to become heroin addicts, many people are compliant on opiate therapy as well (and probably suffer suspicion and mistreatment b/c of the abuse epidemic that has occurred w opiates, some in part to negligent prescribing).

Remember, though, that Dr. Heather Ashton’s work was a clinic with 300+ people who came TO HER asking for her help to get off of these drugs that their doctors prescribed to them. This is the case for most everyone I’ve met in the online withdrawal community over the many years I’ve been active in it. The vast majority of those people are victims of iatrogenesis who took the drugs as directed for many years, sometimes becoming very ill from tolerance b/c they DID NOT increase their dose, but rather continued taking the prescribed amount, thinking it was “medicine” they “needed” b/c their medical provider told them to continue taking it. Most of the people desperately want off and are quite upset about the deception they feel that this was done to them without any informed consent. There are conservative housewives, elderly folks, educated professionals caught in this trap who have no history of abuse or addiction, who weren’t swallowing their Ambien, Xanax or Klonopin and washing it down with alcohol, getting them of the street, and taking them with opiates (other psych meds? yes. b/c often psychiatric misdiagnosis of the tolerance occurs) but instead thinking they are complaint patients “treating” something.

I don’t think the majority of iatrogenic benzo dependence winds up like opiate dependence that results in addiction and sometimes heroin addiction (which is probably why most of the opiates that put people on that path are schedule II drugs and benzos are schedule III drugs). Instead, people just take the benzos compliantly sometimes for years and years and are oblivious as to what’s to come in regards to drug neurotoxicity and severe withdrawal.

Report comment

*CORRECTION: Sorry, I meant… “why most of the opiates that put people on that path are schedule II and III drugs and benzos are schedule IV drugs”.

It doesn’t allow me to edit after the fact.

Report comment

I’m curious, is “iatrogenic dependence” really just the same thing as neurophysiological adaptation? Both ultimately are caused by the medication/therapy itself and both involve tolerance & withdrawal. What’s the difference if any?

Report comment

dolorfinis,

Iatrogenic means: of or relating to illness caused by medical examination or treatment.

And dependence refers to physical dependence which was defined in the article as: a state of adaptation that is manifested by a drug class specific withdrawal syndrome that can be produced by abrupt cessation, rapid dose reduction, decreasing blood level of the drug, and/or administration of an antagonist.

So, ultimately, in regards to benzos, we’re probably talking about the same thing except that iatrogenic just indicates that it’s a result of medical treatment. (Plysical dependence can happen in and be one component of addiction too since people are still exposing themselves to the drugs, but is not a result of medical treatment and also involves abuse and behaviors not seen in physical dependence alone).

Report comment

ok, thank you. I thought it was the same thing but wanted to make sure. Maybe a part of the solution might be changing or adding a dx for neurophysiological adaptation in the DSM if for some reason iatrogenic dependence dx is for some reason not the terminology “they” want? IDK, but seems foolish not to have that distinction. Great article. I’m a chronic pain pt & would like to show my doc, I’m just afraid to do it. Mentioning this type of thing in that setting is almost asking for trouble, unfortunately.

Report comment

.

I didn’t know what addiction was when I started benzodiazepines.

I thought addiction was falling in love with the effects so bad that you just want to keep taking it no matter what.

I started the Xanax 1mg, nice feeling but not the greatest thing ever but it did help with going to bed ‘on time’ like other people did and I never could.

Then I am given clonopin , didn’t help with sleep as well and the feeling was not as nice but I kept taking it.

I had no idea that addiction or dependence or what ever you want to call it was because of how BAD you feel when you try and stop taking it, I always wrongly believed people became addicted because a drug made them feel so good they fall in love with the effects and wanted more good effects.

I ended up in rehab and like the article points out ALL the blame was put on my because “I am an addict” and everyone else takes no blame at all.

The package did say addictive or habit forming or something like that but again I thought that meant loving the effects and I knew nothing about the part where you get anxiety and withdrawals from hell if you try and quit.

They need to redo that warning label so it describes what actually happens in regular words people can understand.

Warning: This drug makes anxiety kind of go away and feels nice but if you take it for a wile and then try and quit you have panic attacks, a scary loss of reality feeling like a trip to hell you cant even imagine and the only way out is to take more of the drug to make that stuff go away.

That’s an honest warning.

And PS of course they called my withdrawals “mania” and gave me the bipolar label and all that goes with that.

Report comment

Hi The_cat,

Thank you for your comments. Part II (to come soon) of this article addresses the first part of your comment about not knowing what addiction was and why the language is so important in reaching people who are probably dependent and unaware b/c they’re not addicted or abusing the drug (stay tuned…). I thought the same thing, FYI, and because I wasn’t addicted or abusing it, I falsely believed that the benzos were safe and why would my doctor prescribe something harmful to me, so the only people who must get harmed are the ones who don’t take it as they’re supposed to (wrong!).

Addiction basically is the behavior of wanting to keep taking it no matter what. It’s the behavior of abuse of the drug (the more descriptive definitions are above in the article as to the differences).

If you were prescribed it for insomnia and took it as directed by your doctor, you were made iatrogenically dependent without informed consent as to the potential for dependence and withdrawal syndrome.

I, too, wound up in detox as my bio states b/c I figured out on my own what was happening after years of illness due to tolerance and toxicity and I wanted off this stuff, but had no idea of the tragic outcomes of cold-turkey or that I was supposed to taper. I was gravely harmed as a result (and am still suffering three years later as a result of that negligence). I agree there needs to be more clear warnings and informed consent from the medical professionals prescribing these and, most importantly, adherence to the 2-4 week prescribing guidelines. I also was falsely diagnosed as having so-called “mental illness” from the tolerance, toxicity and withdrawal the benzos caused.

I am so sorry for what happened to you.

Report comment

I had no idea,

When I tried cocaine with my tough guy friends as a teen I was curious what it did but I was very scared. That’s cocaine, that addictive stuff they warned us about that can trash your whole life.

I did the cocaine, besides the usual bad trip of up all night and depressing paranoid hell when its gone. Nothing really bad happened. It came around our parties sometimes back then. I did it a few times.

Now years later I read on this Xanax package this little pill nice old ladies take for anxiety “may be addictive” ya what ever, I did real drugs and nothing bad happened no way this old lady pill is going to hurt me. No way.

It hurt me more than I could possibly describe.

Looking forward to part II

Report comment

You state that “Addiction basically is the behavior of wanting to keep taking it no matter what.”

Again I’m curious, if addiction is the behavior(s), wouldn’t that mean it is a SYMPTOM of a disease, rather than a disease itself? Kind of like Prader-Willi, once thought of as “the disease of over eating” (behavior), but now known for its real cause, which is leptin deficiency. I’m wondering if addiction is stuck in this pre-carious position like PW was? To clarify, wouldn’t addiction be better understood under this format:

BRAIN DISEASE

1. Addiction (symptom)

2. Decision making disasters (symptom)

3. Evaluation mistakes of self & others (symptom)

Any insight you could offer would be greatly appreciated.

Report comment

Delorfinis

There is no scientific evidence that addiction is a disease. This fallacy is part of Biological Psychiatry’s disease/drug based medical model of so-called “treatment.” It also serves the narrow interests of the 12 Step dominated addiction treatment industry as well, and stands as an impediment to people seeking permanent solutions for long standing addiction problems.

See my first blog at MIA titled “Addiction, Biological Psychiatry, and the Disease Model.” http://www.madinamerica.com/2012/09/addiction-biological-psychiatry-and-the-disease-model-part-1/

Name another disease that you can wake up one morning and decide to stop a certain behavior and you no longer have any of the negative “symptoms” associated with that behavior.

You cannot wake up and decide to no longer have diabetes or cancer, but you can decide to stop drinking or using certain drugs. Now this decision process may be difficult and complex, but never the less, it is still fundamentally a cognitive choice or decision.

Addiction is usually a “process.” Recovery is a process leading to an “event.”

I hope this helps clarify your questions.

Richard

Report comment

Yes, that is helpful and couldn’t agree more, addiction is not a disease. Which is why I had asked if it wouldn’t be better understood as a symptom of a (brain) disease and not a disease itself (kind of like K Blum’s ‘reward deficiency syndrome’ except polygenetic, not monogenetic, and a disease not a syndrome). As for choice, I’ve read works by K Kendler at MCV et al that explore the idea that for some (say 10%) its really not a choice for them as much as a “liability of initiation” in that they were born w/ hypo-functioning neurotransmitters (the brain’s feel ok chemicals) on the limbic level and that phenotypically means those people will inexorably seek out and use addictors in a way that is totally different for them than those born with normal brains, which is why in those cases only addiction would be seen as a symptom of a brain disease. Which is in all actuality very different than Alan Leshners “hi-jacked” brain hypoth which essentially says anyone can be an addict and currently controls prevention, treatment, recovery & public policy despite poor efficacy outcomes. In any case, iatrogenic physical dependency is certainly not the same as addiction as this article points out

Report comment

Just wanted to add that I really do appreciate the input as I am trying to learn as much as I can on these topics. thank you!

Report comment

Delorfinis

You seem invested in still viewing addiction as some sort of brain disease when there is no definitive evidence to support this contention.

Even though K. Kendler is a brilliant geneticist, he, himself, has been VERY invested in trying to support the growth of Biological Psychiatry. To back up this point, he has made statements showing great disappointment when his profession has so far been unable to find the “Holly Grail,” that is, definitive proof of some genetic marker for that which gets labeled as “mental illness.”

He has been part of those scientists and doctors hell bent on finding evidence to prove various “genetic theories of original sin.” All of this serves the agenda of those that want to blame “bad” genes and society’s victims rather that be critical of the systemic institutional oppression inherent within our economic and political system.

Are there some genetic factors in addiction, maybe. We do know that people who have a higher tolerance for alcohol seem to be more prone to becoming addicted. Perhaps because they feel the positive effects for a longer period before some of sedative and more toxic effects take hold.

Also, there is some evidence that Asian people do not process alcohol as efficiently therefore they may suffer some negative physical effects (more than most people) that deters them from drinking excessively.

Also, I once saw a presentation which theorized that people from Celtic countries that endured the potato famine may have consumed whiskey and other self made forms of alcoholic beverages as a way to obtain sugar based calories to avoid starvation. The contention was that over several generations this may have genetically resulted in future generations having a higher tolerance to alcohol, thus be more prone to addiction.

This is still in the realm of speculation. And even if we found out that some people were more predisposed to addiction it may have very little meaning in today’s world given just much is wrong with the majorly flawed environments that surround us.

I believe ALL human beings are genetically prone to develop addictions and the symptoms that get labeled as “mental illness.” No body stands above this happening to them in the right circumstances in a particular person’s life. And most importantly, all human being are genetically predisposed for *recovery* from these adaptive behaviors or coping mechanisms.

Both forms of these coping mechanisms (addiction and “symptoms” such as depression and anxiety etc.) serve an important evolutionary function for our species. They only become a problem when they get stuck in the “on” position.

Delorfinis, you also mentioned “chronic pain” being a topic of interest to you. As to the issue of the human body’s natural tendency to adapt and seek a state of homeostasis in reaction to outside chemical added to the body, you might want to read up on “opioid induced hyperalgesia.”

This raises serious questions about the efficacy of the long term use of opioid pain drugs and the subsequent related proliferation of pain clinics in this country that began in the middle 1990’s. This is all intimately connected to opioid epidemic that is raging throughout the country and raises serious questions about the complicit role of the pharmaceutical industry and certain sections of the medical establishment.

Richard

Report comment

JD

Thanks for your responses.

On the issue of “informed consent,” many psychiatrists and doctors perform a version of so-called informed consent by telling you the dangers (or having you sign a document indicating you were informed/warned) but then go right ahead and negligently prescribe the drugs beyond 2-4 weeks. They do this either out of ignorance or nefariously knowing they will have a patient “forever.”

Benzos are so damned effective in the short term and the doctors know this. This appeals to the worst of their “Dr. Feelgood” persona. Of course, the patient/victim in these circumstances is usually in a state of desperation due to current problems/stressors and related conflicts with their environment. It is the overriding responsibility of the doctor in these situations to redirect the patient to other avenues and resources to solve their problems with anxiety or insomnia.

“Do no harm” is suppose to be their guiding mantra in giving medical care to people. Just as with antibiotics, doctors need to set safe boundaries and know when and how to say “No.” They are failing massively in this area of medicine and Big Pharma deserves more than half the blame.

The negligence and harm done with benzos in today’s world, when looked at from the broadest perspective (numbers harmed and damage done), may represent one of Psychiatry’s greatest crimes against humanity. We must expose these crimes and provide much needed help to all the victims/survivors. I still believe it should be the number one focus of our organizing efforts against psychiatric abuse at this time.

Richard

Report comment

All great points, Richard.

I agree, i don’t think it’s enough to give someone a piece of paper (if it’s given at all) that says “benzos can cause dependence” and have them sign on the line and then prescribe them for years and years. And just telling people they cause dependence without a explanation as to what that really, truly MEANS is not really informed consent. People need to know in detail what dependence and withdrawal from benzos actually looks like (sometimes years of painful tapering and sometimes years of recovering from the neurotoxicity they cause) and how they can fully devastate your life BEFORE deciding if the benefits outweigh the risks for whatever they’re choosing to take them for. None of this happens. I’m not even sure the doctors know or believe it’s possible, to be honest. Or maybe they just don’t want to for financial gain as you mentioned, I don’t know. Stricter restrictions on them or just keeping them in hospitals and medical settings only and adhering to the short-term use guidelines would be the solution to all of this (and of course, in the meantime, allowing the people who are already dependent the time they need to safely taper off in the interim).

It is definitely a crime against humanity and much more harm than good is being done w/ benzos. Too frequently we hear of suicides in the online withdrawal communities b/c of these drugs and their painful, persistent withdrawal syndromes because people feel hopeless that it will ever end and there’s seemingly nowhere to turn for help or support medically.

Then there’s the fact that they actually CAUSE the very thing they’re often prescribed to treat (anxiety, panic- as well as more problems that weren’t there to begin with) after being prescribed too long. Who would take, say, a cancer drug if it’s just going to give you worse cancer in the end?

Report comment

Amen, JD.

I’m into my 23rd month after a year and a half taper from 0.5mg Klonopin….and still hugely impaired. Maybe forever…

There are so many of us.

And yes, the language is important.

Thanks for the article.

Report comment

Hi humanbeing-

There are way too many of us, you are right. And everyday, it seems, new people show up. I am shocked (but not really b/c $$$) that the horror continues after fifty years without something being done to curtail the prevalence and devastation. But it feels like we’re still in the dark ages with the medical profession even refusing to believe in some cases that this is even possible or that the drugs caused it.

Congratulations on completing your taper and 23 months of benzo freedom (although I appreciate it’s hard to call it “freedom” when you feel anything but free as the withdrawal persists for so long). Keep going- I will too. I believe healing will happen in time, as it has for so many before us.

Best to you.

Report comment

This is amazing, J. Doe. Thank you so much!

I have experienced both addictions (to alcohol and cigarettes) and iatrogenic dependence (to benzos and SSRIs), and to me they were clearly different phenomena. Both horrible, but different – exactly as you describe. (Not sure I believe that addiction is a disease, but that may be a minor disagreement here.)

I think this article should be mandatory reading for anyone with a prescription pad, and I can personally vouch for all the points made herein. I’ve been lied to about drug safety over and over by many doctors, have been prescribed benzos for over a decade, have been treated like I was “drug-seeking” when only taking them as directed, have been given dangerous advice about tapering/discontinuation by multiple doctors, have been treated by multiple doctors as if withdrawal symptoms were evidence of returning or emerging psychiatric “disorders,” and have had my experience of protracted withdrawal (I agree that drug neurotoxicity is a more fitting term) flat-out denied over and over by multiple doctors at the time when I needed their help most.

Report comment

Hi uprising,

I respect your thoughts on addiction not being a disease and feel similarly, personally. But I didn’t want to get into that in the article, as it really is another topic in itself. The medical model, however, does describe it as such and so I kept w/ the medical definitions in order to stay on track. I’ve seen other pieces posted here on MIA though that argue the same point about addiction and whether or not it’s a true disease, so it seems there’s certainly debate going on about that topic. What was important to me w/ this piece is making point that they (dependence/addiction) are, in fact, not the one in the same and the harms that occur to the patients when this confusion occurs.

Thank you for sharing your experience in regards to iatrogenic benzo dependence and how you were treated by the medical community. It sounds all too familiar and, as you probably know, most of the stories in the withdrawal communities are much the same. I am deeply sorry that you experienced what you did.

Report comment

Thank you. I’m so sorry that you’ve also had these terrible experiences.

Report comment

What elegant research! Congratulations on taking control of your healing. I did my taper from benzos (and others) before I ever heard of ‘iatrogenic illness,’ which, when I did become privy to it, I realized that this is what had occurred, that the medical treatment had actually made me ill. It was rough, especially since at that time, I knew of no one else in the world who had released all medication after a long period of using them (for me, it was 20 years before I got rid of them). But I did recover fully in time and found my grounding and health once again, as I know people can, with the kind of focus and diligence you are exemplifying.

Very best wishes on your remarkable jouney. No doubt you will continue to help a lot of people by sharing so openly.

Report comment

Alex,

Thank you for your kind and supportive comment. Wow! How inspiring a story and good to hear that you finally did recover fully and escape the psychiatric drugging.

Just curious: Without even knowing you had iatrogenic illness- how did you figure out to taper on your own? Just tried reducing too quickly to face withdrawal, only to get back on and try again until you figured it out…or?

Report comment

I had been on a vareity of meds for a while and functioning ok–I worked and went to school and all that. And when they started wreaking havoc on my mind and body, a psychiatrist began to experiment on me and before I knew it I was on 9 different meds! A cacophany of benzos, neuroleptics, beta blockers for pain management, etc. I was breaking down fast and become totally incapacitated and disabled, ended up in the ER 3 times one summer, from side effects. An ER physician finally said, “You’ve got to get off all of this medication!”

This was right after graudating from graduate school and I suddenly found myself disabled, so I knew I was in for quite a ride. I was scared out of my mind, and I guess I mean that literally.

So I looked around for answers, and eventually sought help from a medical intuit, who reads subtle energy of the body, and she gave me perfect guidance–for me, personally, and my process–about how to get off the meds. I found an expert 5th generation herbalist, started doing Qi Gong, which was vital because my energy was so depleted, and I began an intense meditiation program where I learned to ground to the Earth, and about how chakras work.

That’s what saved me, learning about chakras and energy. This ascends our biology and is much simpler to work with, where energy is malleable and we can direct it with focus.

I was a wreck when I started this program, could hardly speak and certainly not very coherently, and I was filled to the brim with anxiety and paranoid thinking. But I felt very safe in this environment and these were teachers who knew a lot of things about which I had no idea. They were really present and progress focused, and they were fully supprtive of my releasing all medications.

They weren’t doctors, so they could not advise me about this, but the work I did there replaced the need for medication, because not only was I able to find my natural balance on my own, looking at my own energy and working with that in my life, but it taught me how to self-heal. Changed my perspective so much, that everything around me changed. I was a whole new person, integrated.

I’d also been taking a singing and performing class to help me build strength and confidence, and right after graduating from this meditation and energy program, where I cleared a lot of my energy and brought myself into present time, I was offered a part in a play by a director who was taking the class with me. I was shocked and nervous about that, but it was the first paying job that came my way since I had become disabled. I did it, and from that came a career in theater which lasted 7 years until I moved away from San Francisco. I’m established in a small rural town now, very peaceful and grounded–the road I was always meant to be on.

I tell you this to show just how much a shift can occur when we come off the drugs and let our nature run freely. A new path appears, and it’s quite remarkable. For me, it was literally a miraculous transformation. I have terrible stage fright and had never sung on stage in my life, but I faced it and it freed me, completely.

So no, I did not go back and forth because my mind was made up to stay off of them for good, regardless of anything; but I did suffer through what I just kept tagging as withdrawal and also detoxification. I’d say it took about 4-5 years total to compeltely detoxify, this stuff really gets into us and affects our cells.

But herbs are regenerative, whereas chemical medication are DEgenerative, so the herbs and qi gong helped me to rebuild what had become damaged inside me from the meds, while the chakra, grounding and energy work helped me to define myself in a new way, and how to maintain balance, center, and awareness in the midst of distress or chaos, so it was very empowering.

Coming off these powerful drugs really shift our core, so one thing I always recommend is to embrace the unknown, and trust your process to take you to where you are the person you were always meant to be. The meds keep us from owning our true spirit, because we have trouble perceiving it on medication, it suppresses so much of our natural truth and rhythm.

It’s a very challenging road, but keep persevering, holding steadfast to your goals, and there is a great deal to look forward to ,where it gets easier and easier. I’m of the belief that everythign heals, once we apply ourselves with focus and trust.

You can check out my website, and if you want to talk more about this, please feel free to conact me. I’m always happy to answer any questions about meds, healing, transition, etc.

http://www.embodycalm.com

Report comment

J. Doe

This is by far the best article I have ever read about benzo’s.

It’s very obvious that you have been through w/d yourself.

I’m in my 13th year of fighting these drugs. I’ve been hauled off by ambulance twice due to w/d and have been driven to the ER so many times that I have lost count. Every time the hospital treated me as an “addict” and booted me out of the ER. I hope this article spreads far and wide. This country has a problem that needs to be addressed and not addressed by big pharma. Somehow, some way, the people who have lived this need to be heard. With this article you have taken the first step to make that happen. Job well done!!!!!!

Report comment

Dear J Doe, Thank you for this excellent article. It is a major contribution. My psychiatrization also began with Xanax. It was “safe and effective”…..so I was “mentally ill”. How many millions?

Report comment

A topic near and dear to my heart. Thanks for this…really excellent. I am a fellow sufferer. I tapered Klonopin, and also an SSRI. Despite the tapering they have managed to still obliterate five years of my life, although I have managed to hang on to my job, marriage, and family. I was never told what the drugs might do to me. I feel misled extremely and harmed by Western medicine and psychiatry.

I agree that the terminology matters a great deal and am shocked that the medical negligence of detox centers, who’s business it is to know this subject, continues unabated. No one in medicine seems to know or care enough to put a stop to the atrocities going on there.

I also agree the term “addiction” is not at all appropriate – it implies drug-seeking behavior. And I think “dependency” or even “physical dependency,” although much closer to the target, do not fully capture it, as I think you alluded to. To me “dependency” still connotes withdrawal and is too close to “addiction.” This is not what’s going on with psych drugs.

What happens with psych drugs is a physical rearrangement of the receptor systems (new receptors are created or old ones abolished, neurotransmitter levels are increased or decreased, the way receptors systems interact and influence is altered) as the CNS tries as best it can to adapt and function homeostatically in the presence of the drug. To me this is much closer to – and maybe actually is best called – neurological damage (hopefully reversible) as it cannot be reversed over a short time span like other drug withdrawal effects, and remains long after the drug is gone – often years after. The tapering process is truly a physical damage healing process where the CNS has time to slowly reverse the damage done by the drug.

I’d like to move away from the terms “addiction,” “dependency,” and “withdrawal” completely and really get to the root of what is happening by describing and depicting it for what it really is. The terms “addiction,” “dependency,” and “withdrawal” are borrowed simply because we don’t know what else to call it.

Thanks for bringing this subject to light and doing a fantastic job with the extensive research.

Report comment

Great comment, spatler. I totally see your point. For now, with what language we have to choose from, I guess I am ok with “physical/physiological dependence” as it describes the physiological changes that occur in the body when one is taking the drugs. It really is, though, as you describe, a down-regulation of the GABA receptors which seem to get “stuck” in that downregulated position after too long exposure to the benzo agent.

What I believe (and touch on in part II) is that there most definitely needs to be a name and diagnosis for the SYNDROME that occurs when the people who experience this downregulation from use of the benzos STOP taking them (either in taper or too rapidly). And that maybe the name could give greater understanding and a platform for this condition that is so desperately needed.