All the fuss about Study 329 centers on its 8-week acute phase. But this study had a 24-week Continuation Phase that has never been published. Until Now.

We might have Marty Keller to thank for this Continuation Phase. His big deal was the long-term treatment of depression. He made his name on the back of claims that depression was more chronic than people thought, and that treatment might have to carry on much longer than had been thought. Or perhaps industry made his name for him as this was such an appealing idea for them. He rapidly became one of the go-to key opinion leaders for antidepressants, along with Charlie Nemeroff in the US and Stuart Montgomery in Europe.

Rhode Island, and Brown University, must have looked Providential to Pharma in the early 1990s. Peter Kramer of Listening to Prozac fame was there too, also advocating pretty-well-permanent treatment for people who might be somewhat less-than-entirely chipper 100% of the time. Well, would you take off a pair of spectacles if your sight was crisper wearing them? Why treat a drug any differently? We need to get over these Calvinist hang-ups about feeling better on medication, maybe even feeling better than well.

The Continuation Phase

The Acute Phase of Study 329 ran for 8 weeks – slightly longer than usual because the worry even before it began was that it was going to be difficult to show that treatment worked. But then after that the children could enter a further 24-week continuation phase. The idea was to see how ongoing treatment shaped up. The continuation phase was never published. Never even talked about.

To coincide with the Autumn Equinox, the International Journal of Risk and Safety in Medicine has published Study 329: The Continuation Phase.

The full text is available on Study 329.org, along with the reviews from the Journal of the American Association for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (JAACAP).

JAACAP is not IJRSM – what’s up?

The original Keller paper was published in JAACAP. The former editor Mina Dulcan and the current editor Andres Martin and the American Association for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry were lobbied heavily over the years by Leemon McHenry and Jon Jureidini, trying to get them to do the decent thing and retract the paper. In vain.

So it seemed like a good idea to send Study 329 — The Continuation Phase to JAACAP first. We were pretty certain they would refuse it. But they needed to be given the opportunity to dig a deeper hole. And they did. The reviews are published on Study 329.org.

JAACAP

The primary theme of the reviews is: there is too much data here, tell us what it means. Interpret it for us, and then we can tell you whether we agree with you or not. The paper may in fact have too many tables and figures but the key message about Study 329 is that there is no authoritative interpretation. A lot hinges on almost arbitrary categorizations of the data. You the reader need to be able to play around with the data; you may well spot things others have missed. When it comes to adverse event data in particular there is no expertise. Things need to be picked over.

Off a Cliff

There are some things about the Continuation Phase that are almost too shady to pick over too much, and we did not spend time on them. At the end of the Acute phase, for instance, there was an option for patients to continue into the next phase. It’s easy to understand why people doing poorly in the trial might have opted to drop out at that point. Some people doing well can also have been expected to drop out. What is harder to explain is why most of those doing well who dropped out were on placebo. A mixture of reasons were offered such as non-availability of trial medication but two thirds of those dropping out while doing well were taking placebo. This does not seem random. From GSK’s point of view having a large number of people doing well on placebo enter the continuation phase would not have been ideal.

The Findings

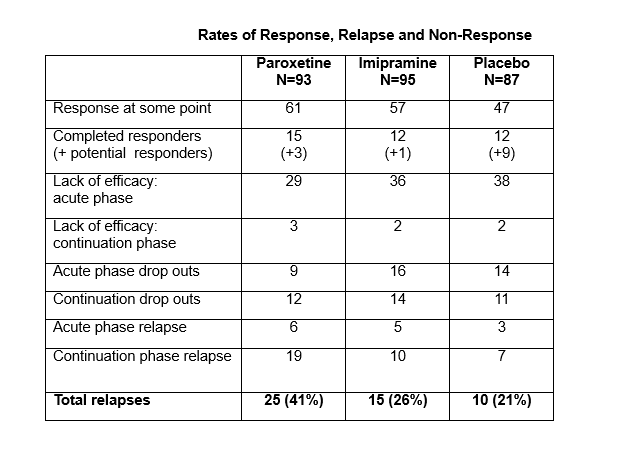

Despite the placebo dropouts, there are more data to pick over in this study that for any other study. The data are not flattering for paroxetine – Paxil / Seroxat.

The relapse rate on paroxetine was higher than for imipramine or placebo. This relapse rate makes paroxetine a Gateway drug. People taking it end up worse off and their difficulties are interpreted as further evidence of illness, and in the real world this is likely to lead to additional diagnoses and additional treatments.

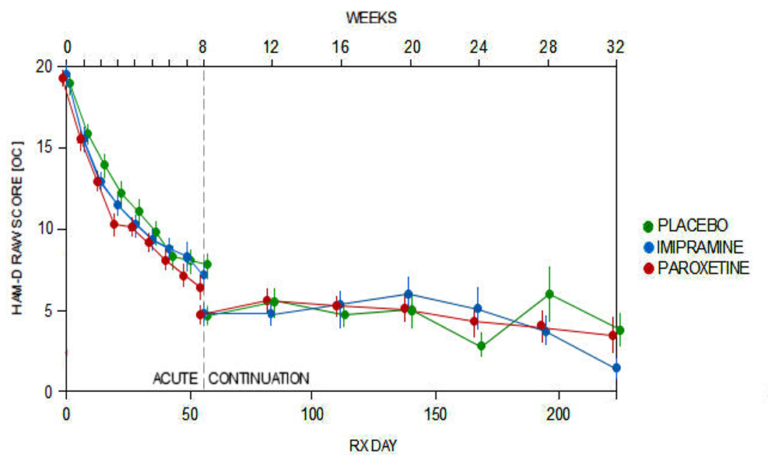

As the Efficacy data above shows, there is no evidence that patients given paroxetine show any benefits compared to placebo over the longer run – even when the deck is stacked against placebo by eliminating many of those who are taking it and doing well.

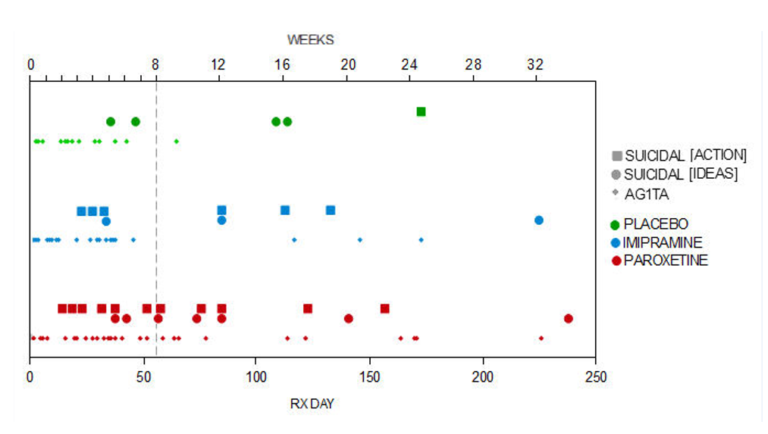

The suicide data also continued to be a problem into the Continuation phase as the graph below shows.

The word AG1TA here stands for agitation.

But there was another even more interesting finding in this paper which will feature in next week’s post. If you download the paper you will likely spot it. Surprisingly, in the light of the finding — or unsurprisingly, given the finding — the reviewers paid no heed it.

To be continued…

* * * * *

Adapted from DavidHealy.org

This is the most important data from Study 329.

What a surprise to see it.

What a Sherlock you are, to get it and to show it to us.

This says all the things psychiatrists used to know, but denied in the 90s.

Shame on psychiatrists who still tell adolescents antidepressents are good working.

Many thanks David!

This is very, very important!

Peter

Report comment

Right on!

Report comment

But discussing whether or not psych meds are effective is legitimating what they are being used to try and do. And this is wrong. It is wrong to try and placate or pacify people, or to put them out of touch with their feelings. Giving someone a real pill, a placebo pill, or trying to do it by talking to them or by getting them to vent, are all wrong.

That it is being done for a study, does not make it acceptable.

Just like it is not ethical to use data from the bogus medical research done in the Nazi Camps, we should not be using research data collected about drugs, when what those drugs are being used for is wrong.

Nomadic

Report comment