A recent review, published in Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, challenges the dominant assumptions about the neurochemical and therapeutic effects of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs), one of the most commonly prescribed classes of antidepressant medication.

“Despite decades of research, the role serotonin plays in depressive phenotypes has not been conclusively determined,” write the researchers, led by Paul Andrews, a professor of evolutionary psychology at McMaster University.

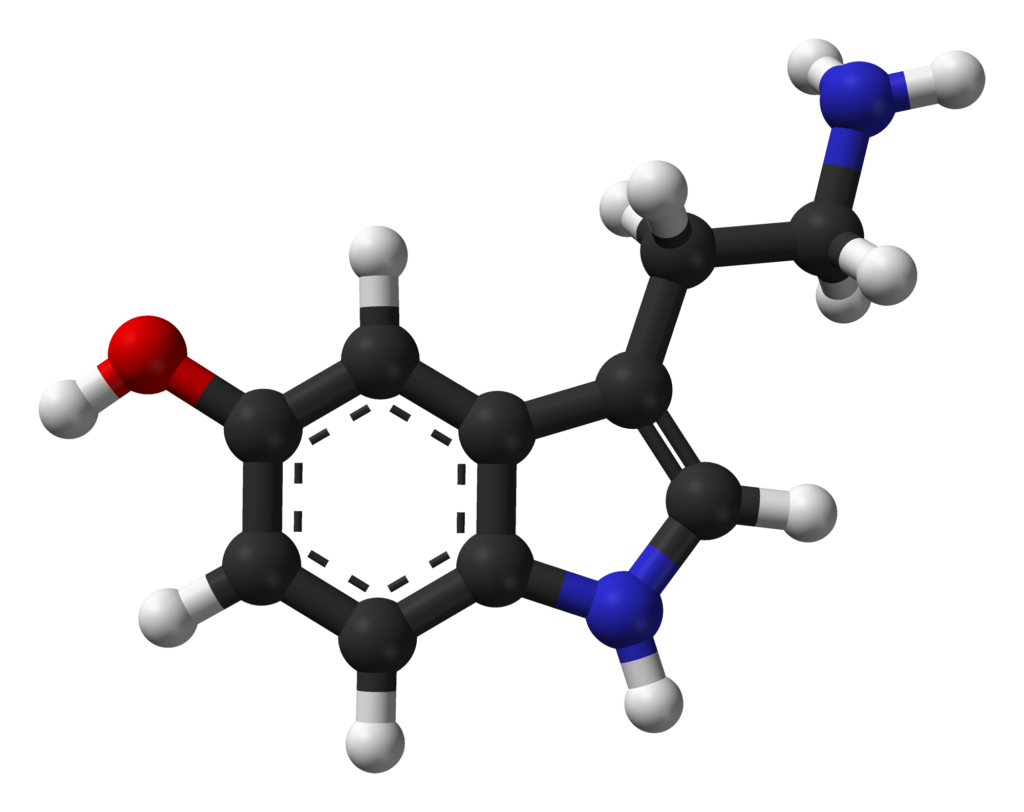

Andrews and colleagues question what they term the low serotonin hypothesis of depression (commonly referred to as the serotonin hypothesis or monoamine hypothesis). This hypothesis suggests that depression is caused by low levels of serotonin in the brain and that SSRIs improve depressive symptoms by increasing levels of serotonin. The authors describe how this hypothesis was developed because of accidental findings: medications that were intended to treat other disorders had the unexpected effect of improving or worsening depressive symptoms. Researchers found that these medications impacted levels of monoamine neurotransmitters (e.g., serotonin, norepinephrine ), which led them to develop SSRIs in order to target increasing serotonin in the brain in order to treat depression.

Andrews and colleagues question what they term the low serotonin hypothesis of depression (commonly referred to as the serotonin hypothesis or monoamine hypothesis). This hypothesis suggests that depression is caused by low levels of serotonin in the brain and that SSRIs improve depressive symptoms by increasing levels of serotonin. The authors describe how this hypothesis was developed because of accidental findings: medications that were intended to treat other disorders had the unexpected effect of improving or worsening depressive symptoms. Researchers found that these medications impacted levels of monoamine neurotransmitters (e.g., serotonin, norepinephrine ), which led them to develop SSRIs in order to target increasing serotonin in the brain in order to treat depression.

However, there are a number of flaws with the low serotonin hypothesis, as Andrews and colleagues note. For example, some drugs that block serotonin do not effectively treat depression. Also, SSRIs increase serotonin levels in the brain almost immediately but therapeutic effects can take weeks, this phenomenon is known as the therapeutic delay. In addition, the authors cite a number of meta-analyses investigating the efficacy of SSRIs that found these medications are only minimally more effective than placebo at treating depression. “Although the idea that a single neurochemical is the cause of depression is now considered simplistic, the low serotonin hypothesis still lies at the foundation of most research on depression,” state the authors.

Andrews and colleagues put forth three major claims against the low serotonin hypothesis. They review both human and animal research to argue for a new understanding of serotonin’s role in the brain and the effects of SSRIs.

Claim 1: The High Serotonin Hypothesis

Research shows that many types of depression actually correspond to elevated, rather than lowered, levels of serotonin. This includes the melancholia phenotype, the most common presentation, expressed in half of all people with depression. Andrews and colleagues call this the high serotonin hypothesis.

Claim 2: Energy Regulation

Why would high levels of serotonin correspond to depressive states? The authors answer this by a radical new understanding of the role serotonin plays in the brain. They suggest that serotonin has an evolved function: “the coordination of metabolic processes with the storage, mobilization, distribution, production and utilization of energetic resources to meet adaptive demands.” Under this theory, there are higher levels of serotonin when there is a need to redistribute limited energy resources. “Serotonin cannot be simply described as an ‘upper’ or a ‘downer’; its symptomatic effects depend on the organism’s state,” write the authors.

Andrews and colleagues propose a new understanding of melancholic depression, “In melancholia, the symptoms reflect a trade-off in which energy is reallocated toward cognition at the expense of growth and reproduction. We suggest that the elevation in serotonin transmission coordinates this trade-off and helps explain many of the symptoms of melancholia.”

Claim 3: Disruption of Energy Homeostasis

Andrews and colleagues contend that the body’s natural response is to maintain an energy homeostasis, and therefore a drug that increases serotonin levels will trigger a reaction in the body to decrease serotonin. With this logic they challenge the idea that SSRIs improve depression by increasing serotonin levels. They make the opposite claim, hypothesizing that, in fact, “it is the brain’s compensatory responses to SSRI treatment, rather than the direct pharmacological properties of SSRIs, that are responsible for reducing depressive symptoms.”

In their theory, SSRIs disrupt the body’s natural process to redistribute energy between different functions and artificially increases serotonin levels, actually worsening depressive symptoms in the short term. The authors explain that in melancholic depression, SSRIs “only reduce symptoms to the degree they induce a sufficiently strong compensatory response by the brain to suppress the allocation of energy devoted to sustained cognition.”

This theory explains the therapeutic delay as well as anecdotal reports that people feel worse right after starting SSRIs because it takes the body weeks to compensate for the serotonin disruption. It also provides a rationale for why individuals taking SSRIs often report that the medication eventually stops working.

“When a homeostatic mechanism is perturbed, it often exhibits a dampened oscillation around its equilibrium, as in the case of a spring that is released from a compressed position. We suggest this is what is happening over the course of SSRI treatment. Acute treatment often causes a worsening of symptoms relative to the pre-medicated state. Over chronic treatment (several weeks) symptoms are alleviated relative to the pre-medicated state, and symptoms return to the pre-medicated baseline over more prolonged treatment periods.”

Andrews and colleagues call for more research examining changes in the serotonergic system from acute to prolonged SSRI treatment, and more research studying their energy regulation hypothesis. SSRIs are one of the most common medications prescribed to treat depression. Therefore, it is vital to better understand how they are affecting the brain and how they lead to changes in symptoms. Andrews and colleagues close by stating, “Understanding the true relationship between serotonin and depressed states will be important in understanding the etiology of those states and developing effective treatments.”

****

Andrews, P. W., Bharwani, A., Lee, K. R., Fox, M., & Thomson, J. A. (2015). Is serotonin an upper or a downer? The evolution of the serotonergic system and its role in depression and the antidepressant response. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 51, 164-188. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.01.018 (Abstract)

These authors appear to assume that (a) antidepressants “work,” (b) that they do so for biological reasons, and (c) these reasons explain the “therapeutic delay” in which symptom reduction takes several weeks to kick in. The scientific evidence does not support any of these assumptions.

“Antidepressants” work almost entirely due to the placebo effect. The pharmacological action of different drugs on serotonin has no relationship to their effects on depression. To the extent a biological explanation is necessary to explain their effects, Joanna Moncrieff’s drug-centered model does the job quite nicely. The therapeutic delay concept is a myth. Week-by-week scores on depression measures during drug trials shows a steady, linear decrease in symptoms that begins in the first week. But it takes a few weeks for that increase to become large enough to be clinically meaningful, hence the misperception that the drugs take a few weeks to “kick in.”

It’s good that researchers have come around to caring about what antidepressants do to the brain, but this work needs to be based on accurate assumptions, and it usually is not. Case in point: the authors’ closing statement, “Understanding the true relationship between serotonin and depressed states will be important in understanding the etiology of those states and developing effective treatments.” This statement assumes serotonin is important to the etiology of depression. It seems the “chemical imbalance” myth is still alive and well despite Ronald Pies’ premature eulogy for it.

Report comment

It’s interesting to me that studies were done where they lowered the amount of serotonin in people to see if depression could be induced and nothing happened.

Report comment

Another interesting item about this class of drugs is that they started as treatments for OCD, where they apparently do work. Somebody got the bright idea that they would work on depressions because they might reduce the amount of obsessive thinking common among certain depressives, not noticing depression is a syndrome, instead of an independent disease entity.

Report comment

“Despite decades of research, the role serotonin plays in depressive phenotypes has not been conclusively determined,” write the researchers, led by Paul Andrews, a professor of evolutionary psychology at McMaster University.

This is a classic example of bullshit in psychiatry. What Andrews actually meant was “Nobody has the faintest clue of the role of serotonin (or any other of the 100 or so neurotransmitters that have been identified) in generating the experience of normal emotion, let alone of what we like to think of as pathological states.”

Report comment

Beautifully stated!

Report comment

The ONLY way that anti-depressants “work” is to MAKE MONEY for the drug companies and the mental-industrial complex…. I tried both Zoloft & Wellbutrin, for 1+yrs. each, at typical “clinical” levels, while working weekly with a licensed clinical psychologist and an MD. Besides waste my time and $$$, the ONLY “effect” we noticed was that the general topic of suicide occurred more often in my thoughts…. And, the nature of the Placebo effect is such that yes, sometimes some folks DO seem to do better for some short length of time on these grossly over-hyped DRUG$…. The first word in the title of this article is superfluous and misleading. Given the title above, the ENTIRE article could be reduced to “They don’t, that’s how”…..

Report comment

At least no-one give any attention to wikipedia.Depression is phenomenon,serotonin imbalance as hypothesis

is proposed explain for it.Sometimes,only crazy people can connect,what can’t be connected.Even on wikipedia,you can find,that entire science in 21st century dealing with hypothesis and phenomenon in matter,of so called mental illness.But biology can explain just everything-real reason for any mental illness are our hormones.Those who oppose this,are either psychologists or psychiatrists.Our employers of Mental Health

system.Humans are guided by hormones,that is evolution and biology.Nothing special about it.Mental Health

system,is rebellion against biology,evolution and my crazy kind in first place.Nature freak I am,not mental.

In abscence of biology,mentality prevails.There are still some strong,primal maniacs,as I am.Certainly they

are only from slavic crazy kind.All others are easily controlled,by psychology or psychiatry.At least my fellow

crazy brethren from USA,you can see real primal madness inside you,now.If you will pay some attention to my comments here,you will be free of mental health issues.

Report comment