A briefing paper released by the British Psychological Society last Friday present’s the evidence for non-pharmacological alternatives to antipsychotics for treating distress in people with dementia. The researchers present the evidence for alternatives in a stepped-care approach, beginning with the least restrictive interventions. The goal of the review is to reduce the over-prescription of antipsychotics to the elderly, which has persisted despite accumulating evidence that these drugs can cause significant harm.

“In practice,” the researchers write, “antipsychotic medication is often used as a first-line treatment for behavioral difficulties rather than as a secondary alternative, despite the evidence that antipsychotic drugs have a limited positive effect and can cause significant harm to people with dementia. Interventions offered should aim to lessen the distress and harm caused by these difficulties and increase the quality of life of those living with dementia and their carers.”

Antipsychotic drugs are known to have a number of severe side-effects, but they carry even greater risks for the elderly and those diagnosed with dementia or Alzheimer’s. Unfortunately, antipsychotic drugs continue to be used as first-line treatments for the control of challenging behaviors in elderly patients. A 2015 study in JAMA Psychiatry found that elderly patients prescribed antipsychotics had significantly higher mortality rates than previously thought, and that mortality was found to increase as doses increased.

Despite the push by government agencies, like the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid, to change these prescribing practices, researchers have found that many elderly patients are still being put on these drugs long-term. The FDA issued an explicit warning that the use of second-generation or “atypical” antipsychotics was especially dangerous for those with dementia, yet, in a research article, published in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, Mark Olfson and his colleagues concluded that about eighty percent of the prescriptions to those over 65 were for atypical antipsychotics. In addition, more than three-quarters of elderly patients receiving antipsychotics do not have a psychiatric diagnosis and the likelihood of taking these drugs increases with age.

Just last month, a study, published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, found that antipsychotics drugs were linked to higher mortality rates even for those with Alzheimer’s that were living at home, rather than in hospitals or nursing homes. The researchers concluded that “Antipsychotic polypharmacy and long-term use should be avoided and drug choice should be weighed against risk/benefit evidence.”

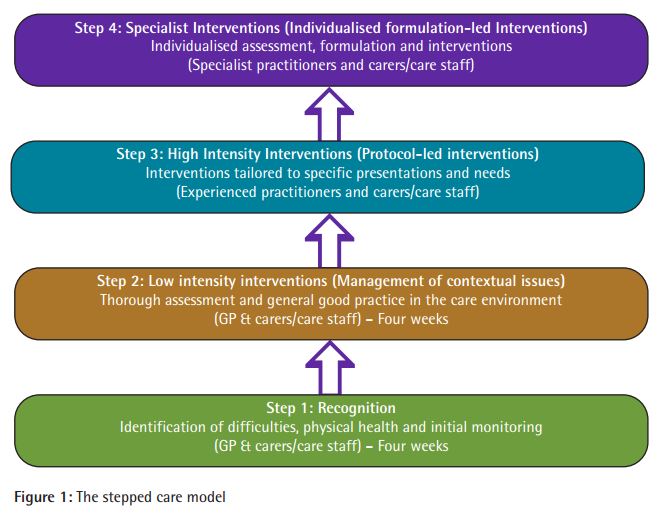

In this latest report by the British Psychological Society, the authors outline a “stepped-care” approach to behavioral interventions for patients diagnosed with dementia who exhibit challenging behaviors in an effort to cut down on the over-prescription of antipsychotics. They estimate that up to 90 percent of people living with Alzheimer’s exhibit some of these behaviors, including hitting, kicking, and screaming, but emphasize “that many of the behaviors identified as challenging are not symptoms of dementia, rather they are symptoms of human distress, disorientation, and misperception.”

The stepped-care approach is designed to draw on the research for psychosocial approaches to these behaviors to identify the “appropriate interventions for the presenting need, reinforcing the message that antipsychotic medication can be implemented as a secondary alternative.” The result is the model (pictured below) that reminds caretakers to ask, “why is the behavior occurring?” and to attempt first to respond to common physical causes of behaviors, and then move on to addressing the patient’s environment, before considering any more intensive or specialized interventions.

In conclusion, the report authors write:

“The stepped care model discussed in this document reinforces the need to ask ‘why the behaviour is occurring?’ and ‘who is it distressing for?’ (i.e. doing a good assessment). This places the behaviour in the context of the person’s life history and the social and physical environment in which they live, and shapes the intervention required. In the future greater care will need to exercised in the prescribing of such medication outside of accepted guidelines, because their limited effectiveness and numerous side effects may lead families to question whether these drugs are being used in their relative’s ‘best interests’.”

****

Read the full BPS briefing paper here: BPS Briefing Paper – Alternatives to antipsychotic medication in people with dementia (2013).pdf

See the BPS press release here: http://beta.bps.org.uk/news-and-policy/bps-briefing-paper-alternatives-antipsychotic-medication-psychological-approaches

these drugs are given out like smarties to elderly confused people round here.

Report comment

“In the future greater care will need to [be] exercised in the prescribing of such medication outside of accepted guidelines, because their limited effectiveness and numerous side effects may lead families to question whether these drugs are being used in their relative’s ‘best interests’.” Antipsychotics are never given in the ‘best interests’ of the person, they are toxic, “torture” drugs, even according to the UN. The neuroleptics / antipsychotics were “torture” drugs given to the Russian dissidents decades ago, and the antipsychotic / neuroleptics are still “torture” drugs today.

“Antipsychotic polypharmacy and long-term use should be avoided and drug choice should be weighed against risk/benefit evidence.” It’s odd that this is considered news to the psychiatric industry, given that every doctor should know that “antipsychotic polypharmacy” can make a person “mad as a hatter” and “psychotic” via anticholinergic toxidrome poisoning. Although many doctors seem to forget this, probably because this known psychiatric drug induced toxidrome is not listed in the DSM as a possible cause of “psychosis.” But at least this deficit in the DSM does result in a lot of unrepentant medical misdiagnosis and maltreatment.

“… more than three-quarters of elderly patients receiving antipsychotics do not have a psychiatric diagnosis,” is this author unaware of the fact that the DSM psychiatric diagnoses have been declared scientifically invalid and unreliable, therefore who cares if they’ve been given a DSM stigmatization or not?

“… the moral test of government is how that government treats those who are in the dawn of life, the children; those who are in the twilight of life, the elderly; those who are in the shadows of life; the sick, the needy and the handicapped.” The fact that our governments have been supporting the mass and forced drugging of our elderly, and our children, with the antipsychotics does not speak well for the morals of our current governmental leaders.

Report comment