A new study, published in the International Journal of Play Therapy, addresses a controversial topic in the field of child-centered play therapy and encourages practitioners to utilize the client’s history in their work. Through exploring theoretical assumptions underlying the debate between knowing or not knowing client background information in child-centered play therapy (CCPT), the researchers argue that knowing background information facilitates empathy and can be a complementary component of the therapeutic process.

“A theoretical framework that draws on person-centered theory and phenomenological psychology has been offered to support appropriate use of client background information in CCPT by situating empathy as an attitude and process that is both affective and cognitive, deeply relational, and aimed at understanding the child’s present and past experiences,” write researchers Goicoechea and Fitzpatrick from Duquesne University.

Child-centered play therapy is grounded in a “deep belief in children’s inherent capacity for growth and self-direction,” founded by Virginia Axline and deeply influenced by Carl Roger’s approach to person-centered therapy. Gathering a psychosocial history, a typical part of the therapeutic process becomes tricky within the context of a fundamentally non-directive approach. CCPT maintains that “the therapist does not direct the focus or content of therapy, nor does he or she aim at changing the child. Rather the therapist attempts to understand the child from his or her frame of reference and to accept the child exactly as he or she is in the present moment to facilitate the child’s own constructive, creative, and self-healing power.”

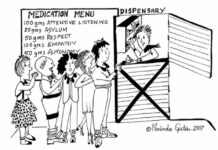

Within the playroom, the child-centered play therapist practices unconditional positive regard, empathy, and genuineness guided by techniques such as tracking, empathic responding, structuring, and limit setting. Empathic responding includes “connecting with the immediacy of the child’s feelings and also more deeply with the thematic elements of the child’s experiences.” Coupled with the ideal of empathy, “circumspect use of client background information is consistent with a child-centered approach.” From this position, Goicoechea and Fitzpatrick offer another angle to the “to know or not to know” debate:

“Rather than treating the tension about background information as a debate for practitioners to situate themselves on either side of, we will explore it as theoretically nuanced, clinically instructive, and as suggestive of the complexity and discipline involved in CCPT.”

Arguments against knowing include the possibility of the therapist guiding, if not coloring, the focus of the session based on background information, risking the nondirective approach. Another concern is the potential to misguidedly interpret the child’s play as connected to their background history. Thus, some researchers caution knowing background information and encourage using empathy in the “here and now” instead of analyzing the play as a relationship of the “here and now” with the child’s past problems.

In contrast, others suggest utilizing background information as helpful hints to the meaning of the child’s play. They indicate that knowing can help the therapist to notice and conceptualize themes, which are “often suggested by patterns, intensity, and other dynamics in the play, [and] are the possible core psychological meanings for the child of his or her play; they are expressions of how the child perceives and experiences his or her world.” Knowing can also support core aspects of the session such as structuring and limit setting. The authors add that knowing can enable systemic interventions alongside play time.

Goicoechea and Fitzpatrick direct their attention to the theoretical foundations of empathy since both stances depend upon the therapist’s ability to execute empathic responding genuinely. Empathy is explored as affective and cognitive, as relational, and as temporal.

In understanding empathy as affective and cognitive, the premise of empathy is reviewed and expanded. For example, the authors elaborate, “empathy consists of pre-reflectively encountering the other’s world, immersing oneself in it and aiming to understand the person from within his or her own frame of reference, but it also necessarily involves entering that world as oneself, with one’s own forestructure or accrued life experience including knowledge of the client’s history and circumstances.” They underscore the need for acknowledging the presence and process of the therapist in the playroom, stating:

“Attempting to remain faithful to the lived experience of the child involves reflecting on how one’s presence and responses may be shaped, in helpful and unhelpful ways, by background information of the child.”

Goicoechea and Fitzpatrick acknowledge Rogers’ perspective of people as not only in relationships but, rather, “as persons we are relationships.” When knowledge of the child’s background can be experienced as evolving within the immediate interpersonal exchange, the therapist can provide differential empathy in the moment towards the client’s self-exploration.

A child’s moment to moment experience is lived less structurally, and “may reveal that events of the past that retain significance continue to be present in the here and now and structure the child’s world and play. The past troubles the present and announces itself in the child’s gestures and communications.”

This article analyzes relevant theory as well as integrates theory and practice regarding the use of client background information. Due to the nuanced work of CCPT, one hope of the article is to help trainees to “tolerate the tension between a not-knowing stance and a conceptual position,” since the ambiguity may detract one’s confidence when first beginning to practice.

More qualitative research about therapists’ experiences using client background information is a warranted next step. While the authors provide case examples to help depict when knowing client background information could be helpful, they do not explore case examples that might benefit from not knowing.

Along with using this theoretical framework for training to increase the knowledge of theory and practice, inspire confidence, and promote CCPT practice, Goicoechea and Fitzpatrick conclude suggesting:

“Future research could expand on these important findings by focusing specifically on beliefs, knowledge, and skills related to using client background information and case-conceptualization within a nondirective framework.”

****

Goicoechea, J., & Fitzpatrick, T. (2019). To know or not to know: Empathic use of client background information in child-centered play therapy. International Journal of Play Therapy, 28(1), 22-33. (Link)

It’s rather staggering that MiA is having to educate the entire “mental health” field that understanding the cause of a person’s distress is helpful, and I would say even mandatory, if the “mental health” workers want to actually help their clients.

How an entire industry could be so staggeringly stupid that none of them know that when helping another person one needs to listen to that person’s concerns, and help them deal with their real life problems.

But absolutely it is true that the “mental health” workers have been ignoring and denying their clients real life concerns. Then they defame their clients with “invalid” disorders, and poison their clients with neurotoxic drugs. This paradigm of harm, fraudulently claimed “care,” does need to end.

Although I don’t see how the ongoing paradigm of “error” and “terror” will ever end, until the “mental health” workers get rid of their Diabolical Stigmatization Manual (DSM).

Report comment

“Play” “therapy” is child abuse. How is this still allowed in 2019? Children are not capable of consenting to this.

Report comment