A study published in the Community Mental Health Journal approaches the phenomenon of hearing voices in a non-pathologizing way and reviews the literature to locate concepts that might improve our understanding of voice hearing. The results of the systematic review reveal three concepts that need to be considered to comprehend hearing voices: “the role of the socio-cultural context, the role of language, and the role of the sense-making process and the functions the voice assumes.”

“Considering contextual and situational aspects in which particular hallucinatory experiences occur or are constructed can help us to understand them, by emphasizing these experiences’ meaning, function and the ways in which they are interpreted and find social acceptance,” write the researchers, led by Antonio Iudici from the University of Padova, Italy.

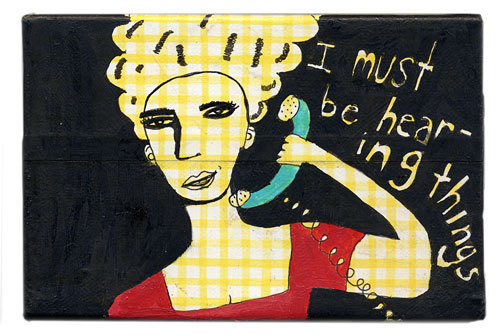

The experience of hearing voices is still more commonly referred to as a hallucination in western society. Hallucinations are defined as “experiences that occur in the absence of external stimuli, emerge mainly when the individual is in a state of vigilance and are not under voluntary control.” Because of their association with psychiatric disorders, individuals who experience hearing voices may not speak out because of the associated stigma.

“The hearing voices phenomenon highlights the problem and complexity of the relationship between auditory hallucinations and the diagnosis of psychiatric disorders and the risk of automatically categorizing hearing voices as a pathological experience,” the authors write.

Iudici and colleagues argue that there is a clear need for clinicians to comprehend better the phenomenon of hearing voices. Toward this aim, they conducted a literature review of psychological studies that approached the experience as a non-clinical entity. Within these articles, they sought to distill the concepts that help to elucidate the experiences of hearing voices. Iudici and colleagues note that the findings can support both hearers and providers, by postulating alternative explanations and starting points to understanding the hearer’s experiences.

The authors reviewed studies from several online databases between the years 1970-2017, resulting in 203 articles that fit within the research parameters. These documents were then analyzed and interpreted by the authors.

Ultimately, they found a “long scientific tradition in which hallucinations are considered a part of the continuum of normal functioning and in which it is therefore accepted that voices can be present in the absence of cerebral dysfunction or psychiatric disorder (see, for instance, Strauss 1969; van Os et al. 2000; Birchwood et al. 2005).”

Three concepts were identified as key criteria to consider for understanding the experience of hearing voices: the role of socio-cultural context, the role of language, and the role of the sense-making process.

The Role of Socio-Cultural Context

Western societies generally perceive hearing voices as negative, except under a “limited range of circumstances,” such as in certain religious situations. The culture of both hearer and provider should be taken into account when assessing the impact of the voices.

“Beliefs about the origin of hallucinations-including culturally determined beliefs-can play an important role in the social control of the production and content of hallucinations,” write the researchers. Thus, “a careful investigation of the socio-cultural context can become very useful to facilitate the understanding and management of hearing voices.”

The Role of Language

The ability to talk in an abstract way or about an abstract event “can be a determinant of whether the experience of hearing voices involves a hallucination or an unusual auditory experience,” e.g. “it is as if I heard…” or “I thought about seeing…” has a lower probability of being perceived as hallucinatory. Other research suggests further linguistic theories, such as faulty monitoring of inner speech and context processing errors. Another offers the idea of several forms of inner speech, and that “hearing of voices could reflect the disruption of the internalization of socially mediated, external dialogue.”

The Role of the Sense-Making Process and the Functions of Voices

Iudici and colleagues emphasize the process of meaning-making within a socio-cultural context, naming prior research that has “pointed out that the way in which hallucinatory phenomena are labeled can be influenced by the beliefs and oral sophistications of both the clinician and the patient. People who hear voices can attempt to make sense of their experience; to do so, they resort to whatever forms of knowledge available to them, whether philosophical, religious, paranormal, or medical.”

The individual’s access to interpretation may shape the relationship one has with the voices. For example, voices may be an attempted solution in the face of a problem, may be considered a form of salvation or persecution (Salvini and Bottini 2011), may give comfort (Freeman and Garety 2003; Hill and Linden 2013), may guide against stress (Evensen et al. 2011; Longden 2017) or disappointments (Kumari et al. 2013), or be an accompaniment to daily life (Hayward et al. 2011).

A limiting factor to this article is the tendency to differentiate between hearing voices for “healthy people” and hearing voices for people with diagnosable psychiatric disorders. This is a challengeable position, as it presumes that psychiatric diagnoses are separate, real entities, rather than patterns reified by specific psychiatric and pharmaceutical agendas.

Ultimately, Iudici, Quarato, and Neri’s study offers an exploration of the existing research on hearing voices which provides context for providers to grapple with when working with hearers, toward a more contextual, empowering approach.

“Some authors emphasize the value of exploring the ‘subjective culture’ surrounding the interpretations and discourses of hearers,” they write, “the clinician should therefore consider the influence of his or her professional group or the socio-cultural context when attributing sense and meaning to the patient’s lived experience.”

****

Iudici, A., Quarato, M., & Neri, J. (2018). The phenomenon of “hearing voices”: Not just psychotic hallucinations-a psychological literature review and a reflection on clinical and social health. Community Mental Health Journal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-018-0359-0 (Link)

Hallucinations are defined as “experiences that occur in the absence of external stimuli”. Sensory deprivation result in hallucinations invariably. The definition in the article is not clear.

Report comment

Wow! Great summary with lots of info! Exciting to see new data on this and wish they were asking a broader range of questions about the experiences. Thanks for this great articulation!

Report comment

“Western societies generally perceive hearing voices as negative, except under a ‘limited range of circumstances,’ such as in certain religious situations.” This is not actually true in the USA. All my “mental health” workers blasphemed either the Holy Spirit or God. They believed that a dream query about what being ‘moved by the Holy Spirit’ means, is a “voice” proving “psychosis.” And they even believed the mere belief in God was a “delusion.” Despite the fact that force drugging people for belief in God is illegal in the USA. Not to mention that definition of “psychosis” means all humans are “psychotic,” since we all dream.

Nonetheless, when you force a person, who is not actually “psychotic” to take the antipsychotics, it will make the person “psychotic,” via anticholinergic toxidrome poisoning. And anticholinergic toxidrome induced “voices” do relate to one’s real life circumstances.

In my case I got the “voices” of the sickos who had abused my child in my head, incessantly bragging about their crimes. The medical evidence of the child abuse was eventually handed over, so the abuse did actually occur in real life.

There was even one point, as I was being weaned off the antipsychotics, where the evil child abusing lady’s diminishing “voice” (since the evil “voices” did go away as the medications went away). A “voice” who’d also been claiming she was the Holy Sprit, did concede she was not the Holy Spirit, and conceded defeat. And what was bizarre is the real life lady associated with that “voice” did lie down on the floor in front of me, as if she were crazy, in a church. Seemingly as if the real lady also conceded defeat. Who knows? I guess it could have been “voice to skull technology”? Or just a bizarre coincidence?

I can’t say for certain, however, I am of the opinion that forcing the antipsychotics onto people does likely leave them vulnerable to attacks by evil spirits. Thankfully, the Holy Spirit stayed with me the whole time, and got me through it. But an antipsychotic induced anticholinergic toxidrome “psychosis” is like living in hell on earth.

And absolutely, drugging people for belief in God or the Holy Spirit is illegal for good reason, so the “mental health” workers should stop doing this. I know it’s happened to lots of people other than just me, because there are online groups of people who’ve had spiritual experiences misdiagnosed with the “invalid” DSM disorders.

So as to whether there is reliable “meaning,” in “context” to one’s life, and spoken in understandable “language” when it comes to “hearing voices.” If those “voices” were created with the antidepressants and/or antipsychotics, via anticholinergic toxidrome, the answer is yes. The psychiatrists are 100% incorrect. But that’s not actually “news” any longer.

Report comment

I wonder if the people doing the study looked at the work and studies done by a psychological anthropologist by the name of Tanya Luhrman. She points out that hearing voices is looked upon in different ways in different cultures and it’s only in the West that hearing voices is looked at in such a negative light. She’s studied hearing voices in Africa, India, and the United States. She’s also written books about evangelicals who say that God talks to them and this raises interesting questions to think about. No one seems to pathologize them due to their claim of hearing God. I think the title of one of them is When God Talks Back.

Where I work I’m not allowed to ask people anything about their voices because to do so would supposedly show that there is something more to them than just being symptoms of their “illness”. The psychiatrists and staff approach voice hearing as being totally devoid of any positive value at all and we’re not to encourage people to think that there is anything useful or positive about them. I do not agree with this approach to hearing voices, at all. I believe that if you can work with a person’s voices you may just be able to help them deal with their issues. But of course, this would go against the paradigm of “care” that predominates everything. And this is why we have a revolving door where I work so that people keep coming back and coming back, over and over again. So much for the good “care” huh?

Report comment