The Mad in America Parent Resources Q&A section is a safe place to ask questions and share concerns about children, families, and alternatives to conventional psychiatric treatments and have them answered on site by one of our subject experts. Please email your questions to [email protected]. Your identity will be kept confidential. Questions may be edited for length and clarity. An archive of past Q & A’s can be found here.

Question:

My eight-year-old daughter, Melissa, has diagnoses of ADHD, depression, anxiety, and ODD. She is taking four prescribed drugs, but she is still suffering and her behavior hasn’t changed much. Her doctor is suggesting adding yet another med. I’m wondering how many drugs are enough? I am starting to think she should go off some of them, but I’m afraid she’ll get worse. I want to trust the psychiatrist, but I’m just not sure anymore.

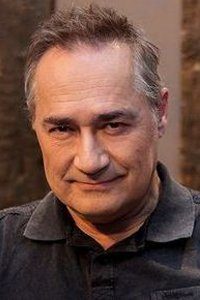

Reply from Ben Furman, M.D.:

Your question is very important. More and more children and teens are taking a cocktail of powerful psychiatric medications. The practice of prescribing such cocktails is called polypharmacy. Polypharmacy is a dangerous development that is worrisome not only to parents but also among medical professionals. Doctors are warned against prescribing multiple drugs to their patients because of the many hazards involved. These include the increased risk of side effects and adverse reactions due to the unpredictable nature of drug interactions. Another cause for worry is decreased quality of life due to the cocktails’ tendency to cause such side effects as lack of ability or desire to exercise, emotional dulling, obesity, and cognitive impairment. This short TED talk by Dr. Russ Altman about the risks of polypharmacy is well worth a watch.

The sad fact, however, is that it is always easier for doctors to add one more medication than to remove one. Patients, particularly the elderly and individuals with mental health problems, are at risk of becoming victims of what has been called a prescribing cascade. This is a type of vicious cycle in which the physician misdiagnoses the side effects of drugs as symptoms of another problem and then prescribes another drug to counteract it — resulting in further side effects, additional diagnoses, and more prescriptions.

As long as drugs are the only tool that doctors feel they have at their disposal, polypharmacy will be an ever-present risk. To avoid psychiatric polypharmacy, we need to make non-drug treatment methods more readily accessible. We also need to educate doctors who can share these methods with their patients.

Multi-Drug Cocktails Are a Red Flag

The rule of thumb in psychiatry is that psychiatric drugs should only be prescribed if there is solid evidence that they are helpful to the patient. It may be helpful to think of polypharmacy as an alarm signal or red flag that the patient’s treatment is overly focused on medication at the expense of other remedies. These options are numerous and include parent training programs, various forms of group therapy for children, summer camps, exercise programs, family interventions, and peer support for parents of special-needs children.

A colleague of mine, Lisbeth Kortegaard, a child psychiatrist from Denmark, was for some years the head of a child and adolescent psychiatric ward in a hospital in Denmark. The ward specialized in treating the more difficult children and teens. All children who were referred to the ward were taking psychiatric drugs, and most were on more than one. Lisbeth was not a big believer in the drugs, so she decided to wean all her young patients off of them. The entire staff on the ward supported her. Tapering was done slowly enough to avoid adverse reactions. Result: All of the children improved. Admittedly, this did not make her popular with her peers who were still prescribing a lot of medication.

I share this story because parents like you sometimes consult me with questions related not so much to how to help their children but to how to influence the system treating their children. Indeed, sometimes it is more challenging to deal with the systems that treat our loved ones than with the person who is having mental health problems.

Talk to Your Child’s Doctor

To understand how to get a psychiatrist to reduce a patient’s medication you need to put yourself in the psychiatrist’s shoes. If, during the consultation, your or your daughter speak to the doctor only about her problems and symptoms, it is not surprising that the doctor tends to increase her medication. To get a psychiatrist to consider reducing the number or dose of medications, he or she needs to hear three things from the patient, as well as from the patient’s family. One, that things are better; two, that symptoms have diminished (or gone away); and three, that the patient feels that the drugs’ side effects are preventing further recovery.

All decent doctors want to optimize their patients’ medication regimen and avoid polypharmacy. The reasons why so many of them wind up adding rather than reducing medication are complex. But they are often related to lack of time reserved for individual patients, the doctor’s wish to do something to be helpful, and an ever-present fear that reduction of drugs might lead the patient’s condition to worsen.

In situations like Melissa’s where polypharmacy has become a problem, I recommend that you seek out a doctor interested in helping patients optimize or reduce their medication. If you cannot find one, I recommend that you and your child talk to the treating psychiatrist about the idea of reducing her medication (or at least, not adding another one). When introducing the idea, bear in mind that doctors usually want to play it safe and may be reluctant at first to make any changes to Melissa’s treatment plan. To get the doctor on board, your family will need to work out a strategy to convince the doctor that the time is right to consider lowering the dose or removing some of the pills from your child’s regimen.

The strategy should be based on taking a positive perspective: Letting the doctor know that Melissa is doing better, that she has future plans, and that you both feel that the side effects are hampering her recovery. The doctor will also want to hear that you are willing to help your child reduce her medication slowly and in coordination with him or her.

Research and Try Drug-Free Approaches

Taking this route requires that your family learn about drug-free approaches to helping Melissa manage her problems. For example, many patients have benefitted from recovery-oriented support groups and many parents have benefitted from support groups for parents of children with mental health problems. Support groups for people who hear voices have become increasingly popular around the world. Guidelines for dealing effectively with specific symptoms are available, including this one I wrote about helping children suffering from aggressive outbursts.

Many parents may also benefit from learning about non-violent resistance (NVR). NVR is a family-empowerment approach developed by professor Haim Omer and his team at the University of Tel Aviv. It empowers parents to deal with children suffering from serious mental health problems but who refuse to accept help.

Every child’s needs are a bit different, so keep your eyes open: Look for multiple, personalized ways to support Melissa that don’t involve drugs. Celebrate small successes and inform your child’s doctor about them to awaken his or her interest in tapering down on your child’s medications.

Ben Furman is a Finnish psychiatrist and an internationally renowned teacher of solutions-focused therapy. He is the founder of the child-friendly Kids’ Skills method, which is based on the idea of converting children’s problems into skills that children can learn with the help of their family and friends. For more information about Ben, visit www.benfurman.com. The Kids’ Skills app is available for download at www.kidsskillsapp.com.

Ben Furman is a Finnish psychiatrist and an internationally renowned teacher of solutions-focused therapy. He is the founder of the child-friendly Kids’ Skills method, which is based on the idea of converting children’s problems into skills that children can learn with the help of their family and friends. For more information about Ben, visit www.benfurman.com. The Kids’ Skills app is available for download at www.kidsskillsapp.com.

Editor’s Note: For a list of individuals and organizations willing to help people come off psychiatric drugs, please visit Mad in America’s Provider Directory. For information on the effects of specific psychiatric drugs on children and youth, and non-drug alternatives, visit the Parent Resources page and click “Drug Info” on the drop-down menu.

It is important to note that many national laws prohibit doctors from forcing children to take treatment without the permission of their parents. The only exceptions are:

_ the child is in grave and imminent danger (road accident, fatal but curable illness…),

_ the prevention of contagious diseases (vaccines),

Apart from these exceptions, circumvented by the law, parents remain free to accept or refuse medical treatment for their child. Conversely, parents can not force a doctor to prescribe a particular treatment.

So:

_ either the family and the doctor find an agreement that suits everyone, especially the child, who is the main interested,

_ either the family and the doctor do not find this agreement, and in this case the doctor is legally obliged to recuse himself, to reorient the family to another doctor, unless the family can find this other doctor by his own means.

Families must be aware that they can freely:

_ accept or refuse a proposed treatment for their child,

_ choose or change doctors for their child.

Doctors are only service providers, outside the family. It is up to the family to find a suitable provider who is attentive to the family members’ requests, especially the juvenile patient.

Report comment

Indeed. You could go to another doctor. Stop taking the prescriptions (very gradually), add another med, or add one and drop one. But, this isn’t good advice without knowing the child, her history, iow, without doing a thorough workup. To me, it is scary and presumptuous for medical professionals to give advice without additional information.

What if great harm comes to the child as the result of following online advice from someone who isn’t in a position to offer such specific medical direction?

This comment won’t survive long, so I’ll send it to Bob, too. I wonder if he is aware of the legal liability he may incur by offering this platform in this manner?

Report comment

POSTING AS MODERATOR:

Why would you think “this comment won’t survive long?” You haven’t violated any of the posting guidelines, have you? We don’t moderate for content here. You can say whatever you want, as long as you are civil and respectful about it. I hope the continuing presence of your comment makes this very clear.

Report comment

What are we talking about? This article or Sylvain’s comment? The article mentions “talk to your child’s doctor” and Sylvain’s comment doesn’t mention anything about randomly stopping drugs.

If it’s the article, there are articles giving medical information online for all sorts of things ranging from breast implants to root canals.

Apart from that, online support groups are formed precisely because people in real life have failed them. A person can’t spend all their life searching for one doctor after another and in the context of psychiatry one may not want to go to doctors at all anymore for several reasons. Anyone who uses the internet should use the information on it cautiously.

Report comment

Coming back to this, gloria fenton’s comment is basically a soft version of “be careful or we’ll sue you” (even though it actually says “be careful or you’ll get sued”).

Children should not be following almost any advice online without parental supervision. That is the parents’ responsibility. Sue the parents, not a place like MIA or patient collaboratives. In this way, every patient collaborative website that has come up should get sued. What when harm does come when people end up in the offices of “medical” men and women?

We should rely only on holy psychiatrists, each of whom one goes go to might add one more psychiatric categorisation on your file. Not.

Report comment