Jussi Valtonen is both a novelist and a psychologist. As a novelist, his work has been compared to both George Orwell’s 1984 and Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World for the way it weaves together social commentary and science fiction to jolt readers into confronting difficult questions about the soon-to-come worlds we are creating in the present. His research as a psychologist investigates how changes to the human brain impact how we think, experience, and make sense of the world. This includes recent investigations of the role of psychiatric drugs and polypharmacy on cognitive decline and functional impairment.

Valtonen is from Helsinki and studied English, philosophy, and psychology in Finland before coming to the US to study neuropsychology at Johns Hopkins University and NYU. He was also trained in screenwriting at the University of Salford in the UK and has worked as a journalist and science reporter.

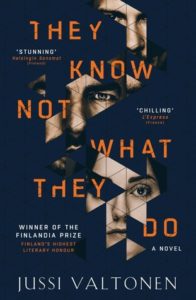

He has written three novels and a short story collection. Carried by Wings (2007) was given second place in Bonnier’s novel competition, and received a warm reception from both critics and bloggers. Valtonen’s recent book, They Know Not What They Do (2014), won the Finlandia Prize, Finland’s highest literary honor.

In this interview, Valtonen discusses how he found psychological science and literature to complement one another, the blind-spots in current psychiatric practice that harm patients, and how novels can help us to ask questions about the world we’re creating.

The transcript below has been edited for length and clarity. Listen to the audio of the interview here.

Gavin Crowell-Williamson: How did you come to be both a psychologist and a novelist? Do you see these two professions influencing each other?

Jussi Valtonen: It’s true, I’ve been leading this crazy double life. To be perfectly honest, I was never sure how long I’d be able to pull it off.

I would strongly recommend against doing this because having even one demanding job that monopolizes all your intellectual space would seem more than enough for anybody. But I guess I’m a little bit comforted by examples of other people who have also felt that science and literature can complement each other.

In the history of literature, Chekhov famously was a medical doctor and also wrote short stories that revolutionized the history of literature, as well as plays.

Personally, I’ve found that science can be intellectually satisfying and fascinating, but it also lacks the perspective of human experience. I don’t know if this is just my personal madness, but it feels to me like art and science are two parts of the puzzle, and you need both to understand who we are and what we’re trying to do.

Crowell-Williamson: Can you just talk to me a little bit about what drove the specific research interests that you’ve developed over your career? For example, you recently published a case study about a 41-year-old woman with a doctoral degree and a successful professional career who gradually became forgetful, visually distractible, and unable to function in her normal occupational and social roles after she added lithium to other psychiatric drugs she had taken as prescribed for years.

Valtonen: The case report we published recently, about the neuropsychological impacts of psychiatric drugs and polypharmacy, wasn’t something that I had intended to get into. The case report was about one of the last patients (SN) that I saw when I was still working at the Helsinki City Health Center psychiatric outpatient services.

My job was to conduct cognitive assessments on psychiatric patients. They often had a psychiatric diagnosis, but they also had some cognitive problems, or there was a worry that something else might be going on, like a neurological disease.

SN was a case where we all (SN herself, Mira Karrasch, my colleague, and I) felt like it was important to document what had happened to her so that other people could also see that information and hopefully learn something from it.

SN came to us because she was worried that she had dementia or some form of progressive brain disease. She felt like something had clearly changed. She wasn’t able to do many of the things that she was used to doing, even things that had been trivially easy for her.

According to her recollection, she had never missed a single day of work in her life before these problems began. Although she had seen therapists on several occasions during her life, her life had been pretty remarkably stable for something like six years. She hadn’t had any abnormal fluctuations in mood or any psychiatric symptoms that would have worried her terribly. But she was convinced that something about her cognitive functions had changed.

I also met with her partner, who was also really worried and also thought that something about her had changed. He was worried that his wife was developing dementia.

Several things worried both of them. One was that she had started missing really important appointments at work. She had also started forgetting to pick up her kids from their hobbies, and forgot to go to meetings with friends.

Things like this occasionally happen to all of us, and sometimes it can be difficult to know what’s abnormal and what’s normal. But in her case, just the sheer frequency of these events and the importance of the meetings that she was missing, were already worrying in combination with her other complaints.

She had, for example, become unable to use the online banking system that she had been using for years. It is easy to use for any neurologically healthy adult, let alone somebody with a Ph.D. in a demanding job.

She noticed that she had trouble typing in the correct sequences of digits; in fact, she had to give all her financial affairs to her partner to take care of because she wasn’t able to do them anymore. Then she had to take sick leave from work.

All of this sounded like something serious was probably going on, and we did the cognitive testing to see whether the test results would corroborate these worries and then hopefully to try to figure out what was going on and try to help her.

Crowell-Williamson: Over the course of your treatment of this patient, she was repeatedly clinically misinterpreted, not informed of the risks, or the side effects of the drug she was taking and didn’t know to associate her side effects with her medication. What do you feel that her experience says about the state of the field of psychiatry?

Valtonen: I think it’s revealing that it hadn’t occurred to anybody that her taking four or five different psychiatric drugs simultaneously might have adverse effects on the brain and her cognition.

Before starting lithium, she hadn’t been warned that something like this could occur. That would have been incredibly important so that she could have noticed it earlier and then have her medication reduced.

One of the tricky things, of course, is that it’s not clear how much we should worry about things like complaints with memory in every individual case because, as we know, some of that happens to all of us. Many authors in the medical literature have argued that the memory problems and the cognitive blurring that people often experience when they’re taking lithium are not things we should worry about, because the benefits of the medication are so important and the side effects are presumably relatively mild.

In her case, however, that was not true at all. But we also don’t know if her problems were caused by lithium alone or if it was lithium in combination with some or all of the other drugs that she was taking.

We do know that polypharmacy, in general, is associated with a higher risk of iatrogenic damage, both neurological and otherwise. So it seems puzzling to me, as a cognitive psychologist, that we aren’t more cautious about these kinds of effects.

If we think about the substantial proportion of people now who are taking psychiatric drugs, often several of them over the long term–in combination with the lack of high-quality research evidence about what those drugs might do to the brain over the long run–that does seem worrying to me.

Crowell-Williamson: Could you talk to me a little bit more about your perception of the risks of polypharmacy?

Valtonen: First of all, we don’t have as much research evidence as we’d hope to even on the individual psychiatric drugs that many people are taking now. Most of the research evidence that we have is, of course, coming from studies that have been conducted over the short term–looking at their long term effects is much more expensive and harder to do.

In the case of lithium, for example, you can find short-term experimental studies looking at lithium’s effects on cognitive processes on healthy human participants. These volunteers have agreed to take the drug for a few weeks. When the drug is discontinued, we can see (in some of these studies) how the cognitive functions recover.

But it would be ethically problematic to do that over a long period with a large group of participants, let alone to cause cognitive deficits experimentally. So we have less high-quality evidence than you’d hope about long-term use, discontinuation, and recovery.

Of course, once you factor in different combinations of several different drugs, the situation becomes even more complicated. The evidence we have is so incomplete and imperfect. Detailed case reports can provide at least some data about the cognitive risks of polypharmacy and about the extent to which cognitive functions recover after the drugs are discontinued.

I’d hope we’d have more and better quality evidence on all of that, but we, unfortunately, don’t.

Crowell-Williamson: Do you hope or anticipate that this work will cause a larger body of research into polypharmacy to follow?

Valtonen: I don’t think an individual case report will have that effect; they are often seen as the least significant category of medical research you can conduct.

In our case, when we were looking at the medical literature and trying to figure out, together with SN, what might be causing her problems, some of the published case reports turned out to be important for us. We noticed that other people also had developed cognitive problems, sometimes very severe ones, during long term administration of lithium.

We also noticed that other cases had been published in which the patients had been misdiagnosed and treated as suffering from dementia. In some of those cases, lithium was discontinued for some other reason, and the patient improved. Only then did the treating team realize it was probably what had been causing the problem all along.

I think there is more general interest now towards de-prescribing and thinking about whether, in some cases, it can be helpful to think about reducing the number of drugs the population is using in general. Hopefully, that trend will continue.

Crowell-Williamson: Of course, this a case study, which comes with certain limitations, as you discussed already. Why did you feel it was important to publish this particular piece, even with those limitations in mind?

Valtonen: I followed SN’s case closely for a long time, and her case was important to me personally. But another one of the impactful things about SN’s case is that none of the problems that she had had in her life, at least in retrospect, would seem that severe. She had never experienced any psychiatric symptoms that would have been considered extreme, where you might kind of go, ‘Aha, I understand now why she was prescribed all those drugs, they must have wanted to do something to alleviate the pain in some way.’

She is a person who had always done incredibly well in her life; she had received the highest grades in school, and she had performed well in a demanding job. All she had wanted was to talk to a therapist about her life and her future plans and her marriage and everyday life seeming things.

So, if a person like this enters the mental health system and becomes medicated to the point of disability and becomes unable to function, both socially and professionally, that seems alarming to me. It just seems to me that her story is a really clear example of how there must be blind spots in the system for it to go this badly and wrong in a case like this.

I should also mention that her cognitive deficits were not extreme. If you look at the medical literature, there are people who have had much worse cognitive deficits. Her story has a fairly happy ending, but still, you can ask what the system was trying to do with her and why it went so badly wrong.

Crowell-Williamson: From your personal experience and your observation of the field at large, what do you see as some of the biggest obstacles to researching the negative impact of certain psychiatric drugs?

Valtonen: That’s a really important question, and also a fairly broad one. It does seem like we have been culturally telling ourselves a story about scientific breakthroughs, and revolutionary treatments that we now have in psychiatry, and about how neuroscience is changing the field, and how we’ve become much closer to understanding how the brain works, and the kinds of aberrations and brain processes that might help explain what ‘mental illness’ is and so forth. I wonder if just the fact that this is the story that we have been telling ourselves and each other as a culture prevents us from asking some of these critical questions.

If that’s the story you’re telling yourself about incredibly precise, targeted interventions in the brain, it’s kind of hard to simultaneously start asking about what we actually know about the long term effects of these drugs and how they actually affect the brain. Maybe one of the things I’m hoping for would be a more scientifically grounded, or more realistic, cultural appreciation of what we do know about the brain and what we do know about these drugs and form a more balanced take on things in general.

Crowell-Williamson: I’m going to transition to discussing your latest novel, which talks about some of these issues as well. First, can you explain why you wrote They Know Not What They Do? What was so important that it needed to be told in that novel form?

Valtonen: That’s a fantastic question. I wish I had an answer to that question. The process was somewhat different. I think if I had asked myself that question, I probably would never have started writing it at all. The process was more along the lines of ‘let’s just see what happens if I try doing this.’

Valtonen: That’s a fantastic question. I wish I had an answer to that question. The process was somewhat different. I think if I had asked myself that question, I probably would never have started writing it at all. The process was more along the lines of ‘let’s just see what happens if I try doing this.’

In hindsight, I think one of the motivations for starting to write the first part of the novel was probably personally trying to understand some of my own experiences after coming back from the US, where I’d done some of my dissertation work. It was kind of a textbook case of reverse culture shock.

People had warned me about that in advance, and I kind of knew about it, but I was still surprised at what happened to me. When you spend a longer period of time abroad, you see your own country differently when you return. It’s a cliché, but it is shocking to experience.

I think that experience motivated me to try to imagine what my country would look like through the eyes of somebody else who came from the US and had a very different background.

Crowell-Williamson: The book has a lot of interesting themes, and you bring up this difference between American and Finnish cultures. Whether that’s a real or perceived difference, that’s certainly a struggle for several of the protagonists. As someone with a foot in each world, what can you tell me about that difference, whether it’s real or perceived?

Valtonen: First of all, I think some of the differences were more real several decades ago. The beginning of the book is set in the early or mid-90s when Finland was facing a historically bad economic depression. That’s part of the context which my American protagonist Joe enters into. [He marries a Finnish woman, Alina, and they have a baby, Samuel. The three of them become the three main characters of the novel.]

Since then, the world has globalized and become much more connected through the internet. Young people growing up probably learn English now even because they’re following YouTube and they’re on the internet.

I also think just the sheer number and the diversity of people, with different cultural and ethnic and religious backgrounds, and the diversity of opinions, still makes the US a really special place. Finland is even a little bit more isolated from the other Nordic countries because the Finnish language is not related to any of the other Nordic languages at all.

Crowell-Williamson: Another theme in the book is this obsession, bordering on addiction, to technology. At one point, a character is trying to stop using this pretty spectacular technological device. And he laments that “he has to generate every thought and impression by himself from beginning to end; how onerous. And worst of all, not a single thought seems to lead anywhere unless he puts active effort into it. No menus open, nothing reacts to his wishes, nor does concentrating on any object bring it to life in a series of increasingly specific choices.” That’s a loaded passage, but I’m wondering if you could speak a little more on the social commentary that underlies it.

Valtonen: Yeah, the novel is interested in our technologically driven culture and why we’re so obsessed with these devices that we’re now using all the time. One of the questions the novel asks is whether this increasingly rapid access to this enormous amount of information helps us to understand each other better.

The passage that you quoted is related to how much mental work it requires if you do something like try to create a world of your own in your writing or produce something in your research that hasn’t existed before. It requires an enormous amount of mental energy. Whereas these devices that we’re using, they’re designed to satisfy us, and we easily become these passive passengers who enjoy the ride.

Once you take the device away, you’re like, ‘Am I really supposed to do all this thinking by myself? Do I have to imagine things? That’s so much work.’

Crowell-Williamson: You highlight how this rapid technological advancement can be dangerous but also how it has a lot of potential. New research is looking at the potential uses of machine learning to predict the risk of suicide and psychosis, for example. That, to me, is interesting and exciting, but also very scary, research. I’m curious as to what your thoughts are on this duality.

Valtonen: I completely agree with you that there’s a duality. Technology promises a lot that could potentially be incredibly helpful and useful, but it’s also scary.

I think one of the reasons why it’s scary is that we don’t seem to have an in-depth social debate over new technology. We don’t have a thorough public discussion when there is a new device that somebody invented where we talk about what the pros and cons are and try to decide together whether we should start using it or not, or what the rules and regulations or checks and balances should be.

We just start using it; they’re on the market, and then legislation is far behind, and only gradually do we begin to discover the potential dangers and problems. Maybe that’s one of the reasons why I’m sometimes skeptical about new technology. I would prefer a slower pace to have more time to discuss what’s going on and how the world is changing and what we think is actually in our best interest as a society and as human beings.

Crowell-Williamson: A related theme in the novel is about research ethics. For some folks, the ethics of research can become blurred when they think that the end result justifies the means. How do you see these issues popping up in the work happening around you?

Valtonen: I think it is a really interesting theme. I never thought about writing a novel that would directly address that theme.

What I had noticed was that in a lot of novels and films, if you see researchers or scientists, they’re often depicted in this incredibly idealized way in which they’re only half-human and kind of above all the petty considerations that you and I might have in our everyday lives. That was something that I kind of wanted to write against.

It seems to me that doing research is in some ways like any other job, and you learn to do what your mentors do and what your peers do. You see who becomes successful and what they did to become successful. In a lot of cases, I think research ethics is not something that people ponder over every day, where they try to make these idealized decisions in the abstract. It’s more like, ‘this is how we typically do it.’ Then you send the form to the IRB, and it becomes your job.

You can’t afford to start thinking really deep philosophical questions every day about your job. You can’t afford to do that all the time if you also want to get something done. That creates the possibility that if things start gradually going wrong, that becomes a new normal, even if it is ethically problematic. You can find yourself in a situation where there’s a systemic problem, and nobody notices it.

Crowell-Williamson: There is this subplot in the book where Joe is waging war against the publishing company. He is continuously waging this battle against essentially the corporatization of scientific literature. All the while, people are losing their jobs, and he’s paying half attention to these meetings. He’s trying to do what he perceives as the good, moral and just thing, but there’s a lot more going on there. Is that, in your mind, a warning on what is to come?

Valtonen: It’s a very real concern. For some of the academic publishers, their subscription fees are clearly not sustainable in the sense that they don’t seem fair from the perspectives of researchers or libraries or taxpayers. People will end up boycotting some of these publishers because they find that their demands are unreasonable.

In that novel, and for me, more generally, it feels like all these different social problems are kind of just attacking you from all sides, and they’re different sizes. Some of them are more national, and some of them are more global, and some of them seem more devastating than others, but they’re all systemic problems.

It seems like if you want to be a good ethical person, you’d have to use a lot of the time that you spend awake battling all these different battles. That’s one of them that is important for Joe, but you could quickly come up with ten others that would feel equally important.

Crowell-Williamson: In Anna Patterson’s review of your book, she writes, “the darkness of the satire is very much Valtonen’s own, and it grows pitch-black towards the end when it becomes clear that we are ready as ever to kill those who might save us.” I found that to be a very profound statement, but I was curious as to whether you agree with that conceptualization of your work.

Valtonen: I like that conceptualization. I’m not sure if it was my interpretation of the work; I mean, I see why she says that, and I think it’s consistent with the work. But I guess for me, personally, what was always most remarkable about the relationship between the father and the son was whether they would be able to find common ground, whether they’d be able to find each other and have a reasonable adult conversation together, whether they would be able to understand each other even a little bit. To me, that felt more important than the sequence of events that then unfolds during the ending.

Crowell-Williamson: If someone puts down your book, finishes reading it, what’s the one thought that you want to be tumbling around their brains?

Valtonen: That’s something that’s up to the reader. Yeah, I guess I’m the kind of an author who would rather hear from the reader what it was for them. What was it for you? What was tumbling around your brain after?

Crowell-Williamson: I think the most interesting idea for me was the duality between the potential and the danger of technological advancements. I could feel it kind of coming in waves in the book and could see it happening differently to Joe versus his older colleagues versus his children. It felt like a red flag being thrown into the air. We’re running into this darkness, and we can’t see very far ahead, so maybe let’s pump the brakes a little bit.

I have been in the past interested in these technologies. I worked in a suicide prevention lab for a couple of years before coming to grad school, and we were very interested in using technology to predict suicide, and I got deep into that headspace. But now I’m taking some steps back and sort of realizing both the danger and the excitement and the possibility of these sorts of technological inventions. That was the biggest takeaway for me, I think.

Valtonen: What I think is beautiful about fiction is that everybody takes slightly different things away from the same novel. If you’ve read a whole novel, some of your thoughts will be the same as with another reader, but some of them will be completely different. For me, that’s part of the beauty of it.

Crowell-Williamson: In terms of your academic and your literary pursuits, as we sit here today, what do you feel passionate about? What do you think is important to investigate, from your perspective?

Valtonen: One of the things that I’ve been excited about recently is narrative psychiatry. We’ve been talking about this with Brad Lewis, who is at NYU. I met him when I was doing a postdoc at NYU. I had known about his work, and I had read his book Narrative Psychiatry, which I would highly recommend.

Once I get to New York, I emailed him and asked him if he had time to meet me, and he did. He was very generous with his time, and I ended up auditing a couple of his classes, and we talked about a lot of stuff.

One of the things we ended up talking about was functional neuroimaging studies of depression and a particular short story that Chekhov wrote in the 1880s. That story, A Nervous Breakdown, is about a young man, a law student, experiences something that gets called ‘a nervous breakdown,’ and his friends take him to see a psychiatrist. It’s a fantastic story. I highly recommend it.

We started thinking about what Chekhov would say about the functional neuroimaging of depression. We’re tentatively working on a project where that’s exactly what we’re trying to figure out. We’re using Chekhov’s short story to think about what it means to think about something like depression in biological terms versus more holistic terms.

Bringing the arts into this conversation feels useful to me. I don’t know if anybody else will pay any attention to it, but we are fascinated by it.

*Photo Credit: Laura Malmivaara / Uniarts Helsinki

****

MIA Reports are supported, in part, by a grant from the Open Society Foundations

The fish on a train saved a man’s life, interesting

Report comment

Interests in others is often interest in ourselves.

Report comment

I was very interested in the physical sciences until I discovered Freud’s efforts to understand the human psyche. This led me to a 50 year career as a psychotherapist, but I was greatly disappointed that no one wanted to hear how psychotic patients could be saved from drugs and institutions with humane insight oriented therapy.

It made me realize that transforming from spiritual religious beliefs to the study of objective reality has had a very negative effect: it has left the human psyche, the soul, neglected and abandoned.

This has led to the pandemic of mental illnesses and addictions that we see today.

I also note the increase in novels and literature, which tells me that people are turning toward this in order to communicate with the inner selves of others in a way that is often lacking in our lives.

I found that a great majority of patients I saw were grateful for the opportunity to express and explore their inner lives in order to improve their lives.

Report comment