Efforts to replace traditional approaches to the classification of mental disorders and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM) have gained traction over the past several years. Researchers developing the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP) approach have moved away from seeing mental disorders as discrete categories and instead cast them within a dimensional framework, seeing symptoms as occurring within a wider spectrum.

In a new article published in Current Directions in Psychological Science, HiTOP researchers Christopher Conway and Robert Krueger present evidence that this new approach puts mental health research, training, and treatment on a stronger scientific footing.

“Our position is that HiTOP provides substantial added value that makes the switch to a dimensional approach worthwhile for most researchers and clinicians. By portraying mental disorders in terms of dimensions, as opposed to categories, HiTOP preserves information about individual differences in mental health, enabling more reliable and valid measurement,” the authors write.

“By deconstructing categorical diagnoses into their constituent parts, it sheds light on the aspects of mental disorder that have the most predictive power. By taking an empirical stance toward classification, it ensures that diagnostic concepts will evolve with new data, not ossify like the many decades-old diagnoses that persist in DSM-5.”

The DSM, now in its fifth edition, is commonly considered the bible of clinical psychopathology. Yet, many DSM diagnoses are based on unreliable standards of evidence. In the last few years, clinicians and researchers have expressed their dismay with the mismatch between the diagnostic paradigm reflected in the DSM and scientific evidence showing that these categories do not accurately reflect populations’ patterns of mental distress.

The DSM, now in its fifth edition, is commonly considered the bible of clinical psychopathology. Yet, many DSM diagnoses are based on unreliable standards of evidence. In the last few years, clinicians and researchers have expressed their dismay with the mismatch between the diagnostic paradigm reflected in the DSM and scientific evidence showing that these categories do not accurately reflect populations’ patterns of mental distress.

Alternatives like the Power, Threat, Meaning Framework proposed by prominent psychologists and service users in the UK have caught the attention of advocates searching for solutions to the DSM’s issues. Another such alternative taxonomy, HiTOP, has recently evolved to address these shortcomings.

In the latest article, the researchers Conway and Krueger, together with the HiTOP Consortium Executive Board, critique the DSM’s construction of mental disorders and explain the advantages of the HiTOP approach, which is based on empirical evidence and responsive to new data.

For the authors, the primary problem with the DSM is its categorical structure. This structure assumes that diagnosed individuals are members or nonmembers in separate, distinctive pathology groups. This flies in the face of common observations about co-morbidity, the finding that people regularly meet criteria for several disorder categories. Research findings suggest that people with mental disorder diagnoses differ from healthy people only in degree (of continuous traits) rather than in kind.

These issues are widely recognized among researchers and are acknowledged by the existing diagnostic systems. The authors explain:

“The American Psychiatric Association and the World Health Organization, which publish the DSM and International Classification of Diseases, respectively, both incorporated some dimensional elements into the recent revisions of their respective diagnostic manuals. The US National Institute of Mental Health, which funds a great deal of scientific work on psychological disorders, went further and jettisoned categorical diagnoses from their latest strategic plan.”

However, the authors believe that the APA and the WHO have not gone far enough. They argue that existing quantitative research on mental disorder signs and symptoms can be used to develop a system of empirical classification based on how symptoms naturally co-occur. For example, symptom clusters of social anxiety may be best understood by envisioning “a continuum of social anxiety, marked on one end by people who crave the spotlight and on the other by those who are desperate to avoid scrutiny.”

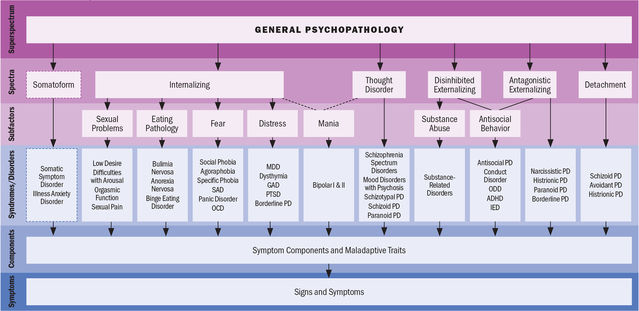

When symptoms are arranged in this dimensional view, they form a hierarchical arrangement. One sees this already looking at current personality and cognitive measures: narrower concepts that correspond to particular events and instances are nested within broader constructs that manifest across a wider variety of situations. In the HiTOP model, they explain:

“Symptom components and maladaptive traits can be thought of as the constituent parts of broader mental health syndromes. For example, social anxiety is a syndrome that brings together various expressions of performance and social interaction anxiety… Syndromes are conceptualized as dimensional tendencies to experience related symptoms and maladaptive traits. In other words, they are continuously distributed concepts, not categories, that span a range of severity.”

HiTOP is compatible with many research programs, utilizing self-and informant-report measures of symptoms. The HiTOP Consortium is also developing a comprehensive assessment system covering the whole model, meaning that clinicians, clinical researchers, and psychologists will be able to apply the model in research and practice settings.

While HiTOP syndromes are based on the same signs and symptoms that make up DSM diagnoses, the syndrome approach offers several advantages over existing diagnoses. By deconstructing categorical diagnoses into their constituent parts, dimensional composites emerge that reflect existing quantitative evidence more closely. The authors hope that this will shed light on the aspects of mental disorders that have the most predictive power and help align diagnostic concepts with new data on an ongoing basis.

The authors conclude:

“HiTOP is ready for implementation now, and it is backed by a solid evidence base. This is a chance for psychologists to move our field in the direction of a more credible, scientifically sound version of mental disorder diagnosis and research.”

****

Conway, C. C., & Krueger, R. (2020, December 3). Rethinking mental disorder diagnosis: Data-driven psychological dimensions, not categories, as a framework for mental health research, treatment, and training. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/9rx6f (Link)

There is another alternative to the DSM and other models. It’s called the psyche model, or The Map of the Psyche: The Truth of Mental Illness.

Report comment

Was this ever put to use to help anyone? Some still think a theory is as good as it helps someone.

Report comment

You’re SUCH a radical!

Report comment

How exactly is this an improvement when it still categorizes disorder based upon symptomatology rather than etiology? The way a person expresses or manifests their distress appears to have more to do with their environment, upbringing, and their social circles than the actual origin of their issues. If psychopathology is ever to have any legitimacy whatsoever, it must address etiology and stop judging and attempting to interpret behaviors.

I can assure you that the behaviors of children experiencing abuse at home or school and adults experiencing domestic violence or abuse in the workplace can look an awful lot like most of these “disorders” and without addressing the situation, the response amounts to victim-blaming. Equally, diagnoses of mood disorders or psychosis when someone has an undetected subclinical infection helps no one. We have a medical system that on a good day does a thyroid and rheumatological panel before drugging the life out of people. We have the knowledge that we are what we eat, that the enteric nervous system directly effects mood and cognition, that hunger and malnutrition are rampant despite people getting too many calories, and yet there seems no political will on either side to regulate lucrative industries peddling cheap crap at great profit to large portions of the populous. And on and on and on. One industry after another profits off of human distress that is largely artificially created.

We don’t need any more research on these issues. We don’t need any more books. We don’t need any more pontificating by academics. We need boots on the ground, we need the folks getting psychology and psychiatry degrees to be raising their voices with us. We need you to read our stories of abuse, of trauma, of illness, of poverty and then elevate our voices to the news and courts and politicians to effect actual change. Fuck this research. Fuck new taxonomies. This isn’t the help anyone needs. This is no alternative to the DSM, it’s just more pathologizing. It’s people getting published in the publish or perish academic environment. You could more good by setting this paper on fire and harvesting the thermal energy from it. At least the PTMF has the guts to point the finger at the power dynamics doing and perpetuating harm.

Report comment

Seems promising, gets rid of the rigidity of the categorical approach which overly reifies the linguistic trap of saying someone “has” a (singular) mental disorder.

Report comment

Huge scientific leap. Way to go psychiatry.

Report comment

Isn’t this kind of like saying “Spoons are superior to forks in digging traffic tunnels?”

Report comment

I thought I’d read through this, as suggested by the number of comments (zero) no one else has yet. But I can see why.

I am probably not even an appropriate person to comment on the DSM, or any suggested replacement, as I am of the conviction that the whole system should be jettisoned, and psychologists be encouraged to return to studying rats. The subject has so far been relatively useless to the human race. Maybe they can figure out how to make rats happier.

I might mention, though, the major “dimension” I have been trained to look for in anybody: Emotional tone, or you might say, “degree of happiness.” It is possible to look at 29 different observable behaviors, plus several more that are observable in therapy, that all correlate to this single dimension.

If the person improves in this dimension (“gets happier”) then you know you have a workable therapy (at least for that person).

Psychology has been in its rut for a long time now. As far as I can tell they have gone seriously subterranean! If it weren’t for a few dear people in the field who have helped me, I would be inclined to totally disregard it.

Report comment

The lack of a means to objectively determine if something “works” is the achilles heel of psychological therapy. People argue endlessly about what “works best” without any definition of what “works” really means.

Report comment