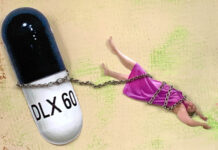

The process of discontinuing psychotropic medication can be difficult to navigate due to a lack of clear information and support regarding how to best go about tapering.

A new article, featured in the Journal of Critical Psychology, Counselling Psychotherapy, highlights these issues. The authors were led by Volkmar Aderhold of the University Clinic for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy in Hamburg-Eppendorf. They discuss barriers to discontinuing psychotropic medication and providing suggestions regarding how to stop taking psychotropic medication safely.

“No one can predict how a psychotropic drug discontinuation process will go in detail,” they write. “Mainstream psychiatrists are only interested in problematic discontinuation attempts, not in those that succeed, especially when people stop taking psychotropic drugs on their own. The number of those who discontinue without problems is unknown; they do not appear in any statistics.”

A key factor to successfully discontinuing psychotropic medication is access to supportive, competent physicians who can assist their clients in tapering in such a way that is safe and minimizes withdrawal symptoms. Unfortunately, however, doctors traditionally do not learn how to most effectively taper people off medication, focusing instead on putting individuals on medication.

The authors caution patience when tapering, advocating for a gradual process. Others have echoed this sentiment, calling for a measured approach to tapering from antipsychotics and antidepressants. The transition from the final dose to no medication should be taken with extreme care, as individuals have reported experiencing withdrawal symptoms after completely stopping their medication. If taking small doses is difficult due to the type of capsule or tablet being used, the authors suggest requesting prescriptions for individual dose preparations to make tapering easier.

Suggestions about discontinuing psychotropic medications that address physiological, psychological, legal, environmental, and other domains are made. They recommend learning about potential withdrawal symptoms and half-lives of psychotropic drugs, as some symptoms can last for months or years. They urge individuals to avoid doctors who try to talk them out of stopping their medication. Becoming aware and informed of the potential impacts of stopping medication on access to resources like welfare or housing benefits is key.

Having a secure support system of individuals who are aware of the plan to discontinue, including informal and formal supports such as doctors, will also assist in the process of tapering. Along similar lines, reaching out to others who have been through withdrawal and can provide support is recommended. The role that service users play in assisting researchers with developing safe, individualized approaches to tapering has been explored elsewhere.

The effects of physical and psychological withdrawal symptoms can be made more bearable by having a quiet environment, engaging in exercise, practicing good nutrition, and getting enough sleep. The authors suggest drinking herbal teas, eating chlorophyll-rich and Sulphur-containing foods, which include things like green plants, herbs, vegetables, and more, and using naturopathic remedies as well as taking omega-3 fatty acids, folic acid, vitamin C and E. Engaging in mindful, self-care activities such as spending time with friends, listening to calming music, writing, planting, playing with animals, and so on, can also assist in easing the tension of the withdrawal process.

Addressing the legal domain, the authors suggest that individuals obtain legal direction if possible to protect themselves against potential compulsory administration of psychotropic drugs and forced treatment. They warn that refusing to take neuroleptics like clozapine has been used to justify forced electroconvulsive therapy.

Moreover, the authors emphasize the role that self-responsibility plays in the process. Individuals stopping medications assert responsibility for their own person and begin to understand the deeper issues underlying their mental health symptoms. Understanding the underlying issues and making necessary life changes is crucial to maintaining a life free of psychotropic drugs.

“One reduces the danger of being prescribed psychiatric drugs again so quickly if one learns to take one’s own feelings seriously, to follow one’s own intuition, to deal with the meaning of depression and psychosis, to recognize one’s own active contribution to psychiatrization and to look self-critical in the mirror, to assess one’s own vulnerability, to recognize warning signs of emerging crisis situations and to react accordingly.”

There are several resources available with further advice on safely tapering from psychotropic drugs, including:

- “Competent help when discontinuing antidepressants and neuroleptics” by Jann E. Schlimme (2017) offers guidelines to stop psychotropic medication use.

- Other resources include www.absetzen.info, the book, Coming off psychiatric drugs: Successful withdrawal from neuroleptics, antidepressants, mood stabilizers, Ritalin and tranquilizers (Lehmann, 2004, 2020), which offers cross-cultural, first-hand accounts of discontinuation and withdrawal, in addition to highlighting the perspectives of relatives, doctors, therapists, and other professionals who assisted in the process of tapering.

- Professional associations, such as the German Society for Social Psychiatry and the British Council for Evidence-based Psychiatry, also provide information regarding how to reduce risk when stopping a medication.

Lastly, the authors implicate doctors who do not provide adequate education about the risk factors associated with psychotropic medication as contributors to failed discontinuation attempts and perpetuate continued, unsolicited administration of psychotropic drugs.

They highlight the work that a group of German psychiatrists has done in providing clear, informed consent to potential patients about the risks associated with medication and alternatives to medication. They also offer assistance with discontinuation from the beginning of treatment, which should become the norm in psychiatric care instead of the outlier.

****

Aderhold, V., Lehmann, P., & Rufer, M. (2021). Discontinuing psychotropic drugs? And if so, how? Journal of Critical Psychology, Counselling, and Psychotherapy, 20(4), 66-75. (Link)

These recommendations put all responsibility for coming off and staying off psych drugs on the patient. If the patient has trouble finding a doctor who is willing to listen to the patient, provide informed consent, and/or support the patient in the often extremely arduous, painful, and sometimes life threatening process of coming off prescribed drugs, then the patient needs to keep looking for a doctor who will do these things which is like finding a needle in a haystack, or the patient needs to find a book or a website for support. Not everyone has a support system in place for something like this. Often people wind up in psychiatric treatment simply because they have no support in their life, because they have been traumatized and are afraid of people. Not everyone has the capacity to carry out these suggestions. When a person is bedridden, as I was during cymbalta withdrawal, it’s very hard to shop for healthy food and prepare healthy meals.

I can attest that during the 1990s and early 2000s, when many new psych drugs came out and were being touted as miracle cures, there was absolutely no information or indication of how dangerous these drugs could be and there was no suggestion that stopping the drugs could be dangerous. I was prescribed one drug after another for 6 years by a psychiatrist who didn’t keep any records of what he was prescribing to me. It’s all a blur of Prozac Paxil Klonopin Wellbutrin Effexor Zoloft Adderall. And then I was labeled with treatment resistant depression and sent for ECT treatments. Then I was labeled with borderline.

The best thing a person can do is avoid psychiatry all together and these suggestions prove it. If you never go on the drugs in the first place you don’t have to worry about how you will get off the drugs. Things like eating healthy foods, exercising, spending time outdoors and with animals… these can all be done without the help of psychiatry.

Report comment

“Moreover, the authors emphasize the role that self-responsibility plays in the process. Individuals stopping medications assert responsibility for their own person and begin to understand the deeper issues underlying their mental health symptoms. Understanding the underlying issues and making necessary life changes is crucial to maintaining a life free of psychotropic drugs.

“One reduces the danger of being prescribed psychiatric drugs again so quickly if one learns to take one’s own feelings seriously, to follow one’s own intuition, to deal with the meaning of depression and psychosis, to recognize one’s own active contribution to psychiatrization and to look self-critical in the mirror, to assess one’s own vulnerability, to recognize warning signs of emerging crisis situations and to react accordingly.””

Nothing to disagree with here except for the timeline and the emphasis on individualism. I had to get off the drugs and spend several years recovering from them before I had the wherewithal to create this kind of emotional growth. Psychoactive drugs inhibit these thinking and emotional processes.

What KateL says above is spot on. I don’t think I could have gotten through that period without the substantial live in support of my (now) husband. If he hadn’t basically forced me at times like an addict to continue on with the withdrawal process, there many times I would have checked myself into a psych unit and gotten right back on the drugs.

I think this article downplays how excruciating that process is. The best way for therapists to help people off the drugs is to stop referring them to psychiatrists. The way to effect that is to lobby to change teaching and licensure guidelines at the state level that include the drugs as a recommended (sometimes first line) treatment. Second is to lobby your state houses to enact insurance legislation that will allow SDOHs as an alternative to DSM labels to cover payment for social work and therapy.

Instead, what we get is this:

“If there’s a true neuropsychiatric sequence after COVID, or there was an underlying health disorder that was not treated in the past if that comes to the forefront, then yes, we have to treat them with medications,” Dr. Shetty said

https://www.wbtw.com/news/study-mental-health-prescriptions-nearly-double-during-covid-19-doctors-treat-2-types-of-disorders/

As if ANY of the labels are valid or correspond with manipulating brain chemicals. Therapists funnel patients to psychiatrists because they’re part of the pipeline designed to do just that.

But here is a real killer. 1 in 3 post-Covid patients are being labeled with psych diagnoses and it’s only the first time for 13% of them!

https://www.ktsa.com/1-in-3-covid-survivors-diagnosed-with-mental-health-conditions/

This implies that by later in life (as the deaths ages are skewed for Covid) nearly 90% of us has had at least one psych label somewhere in our file!!! Where anywhere in the literature is this idea supported that we are nearly all “mentally ill”? This is some of the most striking proof, if we needed any more, that life’s ills are being labeled and drugged instead of helped in any meaningful way and that almost all of us are caught in the web.

Report comment

I realize belatedly that my math ability is shit at 5:30 am. If one in three post covid patients get referred to psychiatry and 87% of those had a previous diagnosis, that suggests that the people who already had psych diagnoses are now having their long haul or post acute symptoms explained as psychiatric rather than physical. How sad!

Report comment

Thank you for backing me up, Kindred Spirit. The difficulty of getting off the psych drugs – and in some cases, dealing with long term damage caused by the psych drugs – should not be minimized.

Report comment

My own “active contribution to my psychiatrization” was falling for the “don’t be afraid to ask for help. Help is available” propaganda. The psych drugs, the labeling, the trauma of “receiving help” and the subsequent loss of physical health, isolation and ostracization were major components of what kept me psychiatrized.

Report comment