In my main field of research—antidepressant drugs for depression—a common reply to studies challenging the efficacy of these drugs is that they clearly work in a meaningful and consistent way, otherwise drug regulators would not have approved them in the first place.

In fact, drug regulators frequently approve drugs despite contradictory clinical trial results, and are letting medicines onto the market that do not provide tangible clinical benefits to most patients.

- Approval Despite Contradictory Trial Results

New psychiatric drugs are commonly approved by drug regulators based on two (occasionally merely one) positive randomised controlled trials. Positive typically means that an investigational drug was more effective than a placebo pill.

However, drug regulators do not require that a drug was shown to be effective in a majority of trials. In fact, a drug could fail in most trials, but if it was superior to placebo in at least two (occasionally even one) trials, then a license will be granted.

This is a controversial approach that various experts consider inadequate and overly permissive. Assuming that all trials were well conducted and adequately powered, then the rate of successful trials conveys important information about the reliability of efficacy estimates.

If a drug’s efficacy was demonstrated in most or all trials, then we can be much more confident that the treatment effect is robust, generalizable, and consistent across patient populations than when efficacy was demonstrated in only a minority of trials.

Unfortunately, many antidepressant drugs failed to demonstrate efficacy in a majority of trials submitted to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for marketing approval.

Among others, this applies to citalopram (only 2 of 5 trials positive), sertraline (1 of 5 trials positive), and vilazodone (2 of 7 trials positive).

If you do not think that this is problematic, imagine the following scenario. A football coach selects two players as penalty shooters because they scored a penalty in at least two different games. However, whereas player one scored only two of seven penalties overall, player two was successful in six of six attempts. There is probably no need to ask which player is the more reliable penalty shooter – but to determine that, we need to know each payer’s overall success rate.

- Approval of Drugs That Provide No Clinical Benefits

A positive trial means that the difference between investigational drug and placebo was statistically significant, but this does not necessarily imply that this difference is clinically significant (practically relevant).

The directors of the FDA have made clear that they base their decisions to approve drugs on the statistical significance of a result, and not on the size (or practical relevance) of a treatment effect.

However, a treatment effect can be statistically significant but so small that it has no discernible impact on the patient’s health whatsoever.

As expert statisticians constantly remind us, “a p-value, or statistical significance, does not measure the size of an effect or the importance of a result”.

If you have difficulties in understanding the difference between statistical and clinical significance, imagine the following scenario. In a clinical trial, a new diet pill led to a statistically significant reduction in body weight compared to a placebo pill. However, the new pills only helped patients to lose 100 grammes of weight. Thus, although this effect might be statistically significant, it has no practical relevance for patients.

With respect to antidepressants for depression, it has consistently been found that the average treatment effect (i.e., drug-placebo difference across trials) is small, just about 2 and 3 points, respectively, on the two most commonly used depression rating scales, the Hamilton depression rating scale (range: 0 to 52 points) and the Montgomery-Asberg depression rating scale (range: 0 to 60 points).

The clinical benefit is thus questionable and may fall short of a minimal clinically important effect for most patients with depression.

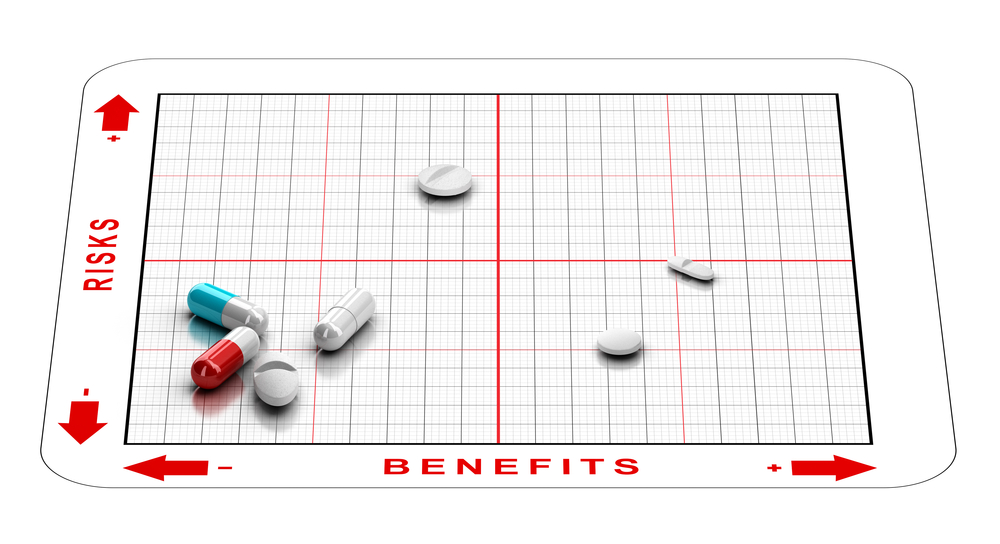

In sum, the combination of approving drugs based on a minority of successful trials and not requiring that treatments have demonstrated, in addition to a statistically significant result, at least a minimally clinically important effect, implies that drug regulators frequently approve drugs with uncertain clinical value that may provide no added benefit to most patients.

Editor’s Note: This article also appeared simultaneously on TranspariMED.

You would need to conduct 40 trials on average to get two of them to show that salt is a statistically significant cancer medication.

Any approval process that could get salt approved for cancer treatment is obviously faulty.

Also, as I’ve written you per email, concluding that medication which lowers depression symptons treats depression is a non sequitur, as the correlation between depression and depression symptoms is unknown, even if you assume that depression exists.

Report comment

Thank you so much, Michael, for truthfully reporting that “drug regulators frequently approve drugs with uncertain clinical value that may provide no added benefit to most patients;” information that is, primarily via hard earned common sense, obvious to most of us here at MiA.

But given the worldwide “fierce Pharma” promotion of the EUA Covid “vaccines.” This common sense reality – regarding the systemic fraud and criminality of “fierce Pharma” – is relevant information for all to be awakened to. Thank you for speaking the truth.

Report comment

We need a deep dive book or article on all aspects of the regulators, history, staff, finances etc. In the UK the MHRA is split into two parts, medical devices and pharmaceuticals – the latter is wholly funded by drug companies and for most of its history headed up by ex pharma management. I understand the FDA’s funding is about 70% drug company money. The regulators are paid for and staffed by the very industry is meant to regulate – what could possibly go wrong?

I can find this from 2004 and you can be sure its even worse now

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2004/oct/04/health.businessofresearch1

Report comment

Many popular drugs do not benefit most patients. For example, without pre-existing heart disease 98% of people do not benefit from statins and statins do not extend lifespan. There’s no adequate evidence that blood pressure medications help people with mild hypertension (under 89/139).

I don’t think most people understand the limited benefit of many treatments physicians frequently prescribe.

Report comment

One way to express the clinical insignificance of 2 points is to show several ways someone can achieve 2 points on the scale.

Here are 4 ways to get 2 points in the the HAM-D scale

-Agree that you are mentally ill

-No longer losing weight

-Instead of asking for help or complaining you are now self absorbed

-No longer play with your hands or hair

The psychiatrist finding any of those means you’ve achieved the reported benefits of the drugs in heavily biased and flawed studies designed to make the drugs look effective.

Report comment