I pause in front of the locked door. My body goes numb as nausea washes over me. I wish I had worn a t-shirt proclaiming, “Just visiting.”

I’m finally allowed to see my friend who has been incarcerated in a psychiatric ward for the past three weeks.

I can’t delay my visit any longer. It’s time to push the buzzer and confront what awaits me on the other side.

The ward is eerily quiet, except for a woman’s voice shouting down a corridor. A nurse checks my bag for sharps.

Cartoonish artwork hangs on bulletin boards with motivational quotes: “What you’re looking for is not out there, it is in you,” and “Self-care is how you take your power back.”

Fifty years ago, in a similar place, there were no motivational quotes on the walls. There was nothing on the walls but peeling paint.

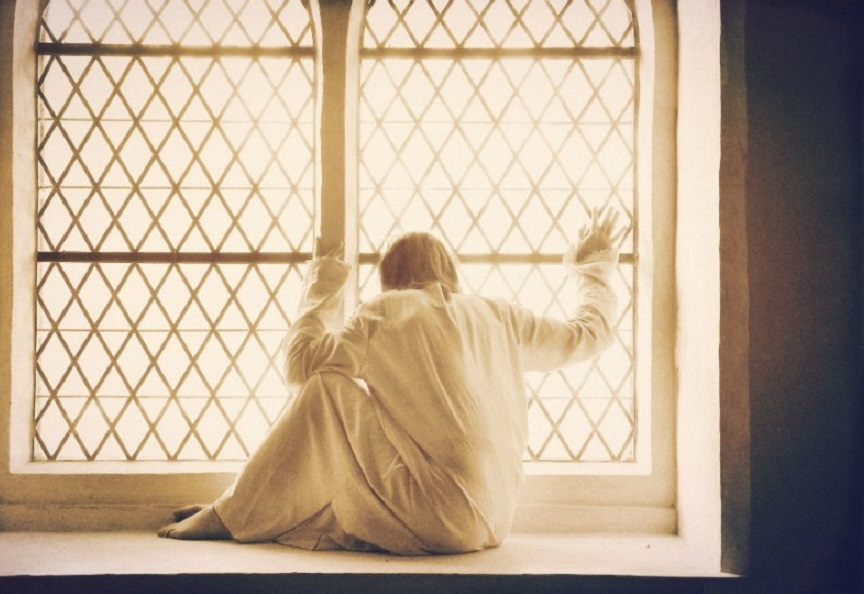

Fifty years ago, there were bars on the windows.

My body buckles under the weight of my secret past, keeping me low to the ground, leading me to choose toxic relationships that remind me of home. Shame is the name of the boulder I carry on my back.

Years ago, my family sent me to psychiatrists who tried to determine what medication would fix me. They all agreed something was wrong, despite, or because of, an ever-changing cocktail of prescription drugs.

I was a rebellious, promiscuous, pot-smoking teenager who didn’t know how to lie.

I remember taking pills, so many pills!

I wrote poetry nonstop. I believed I was the reincarnation of William Shakespeare.

During a three-week stay at a local hospital, I paced the halls instead of sleeping. Sorting stacks of magazines in the patient lounge gave me something to do while waiting for sunrise.

When given a brochure about The Institute of Living, my father commented, “I’d like to go there!” as he pondered the schedule of classes, lectures, and movies.

I realized I had no choice — I would be committed if I refused to go voluntarily.

* * *

Three nurses chased me down the hall, then forced me onto a bed, while another injected me in the thigh. I woke up far away. Naked. In a seclusion room.

Carved into the lintel above the door was the institution’s original name, Connecticut Retreat for the Insane, founded 1823. When I arrived at the asylum in 1971, their stationery, brochures, and other collateral material had been re-branded with the more palatable name, The Institute of Living, the name they still use today.

I had read about such places in The Bell Jar, I Never Promised You a Rose Garden, and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. For more than a year, this place was my home.

I was nineteen years old.

Lobotomies had been performed here into the 1960s. In the modern ’70s, psychiatry relied heavily on medications as well as seclusion rooms, wet-sheet packs, insulin, and electric-shock therapy.

Somehow, I arrived at this place yet had no memory of the journey. Valium, Haldol, Lithium, Melleril, Elavil and Tofranil. These are the names of the drugs I had been prescribed. Once I arrived at The Institute of Living, the doctors put me on ever-increasing doses of Thorazine, a drug no longer in use today because it caused severe cardiac arrhythmias.

* * *

I shuffle in a conga line of hospital-gowned inmates, waiting my turn. When I reach the kitchen door, I’m handed a slice of rhubarb pie on a white paper plate.

I take an empty seat at a long wooden table across from The Druggies.

“Can I have some more of this humble pie?” The Druggies cackle but they can’t agree on what kind of crazy I am.

I can tolerate a substantial dose of Thorazine and remain on my feet. The Druggies want me to share my meds.

“No way am I giving you my pills,” I tell their leader.

Outside the nursing station at the next meds lineup, I discover that I’ve been put on mouth check. I must open my mouth wide and lift my tongue, first to the left and then to the right, while a nurse probes my tonsils with a tongue depressor. She must use a flashlight to make sure I’ve swallowed. It’s humiliating but mysterious, this power the nurses have, making them privy to every exchange and secret that takes place on the ward.

Soon I’m invited to make wine with the Druggies using empty plastic shampoo bottles, pilfered packets of sugar, and green grapes left over from lunch. Every night we hole up in different rooms, timing our efforts between hourly room checks. We sit in a circle and shake the bottles like shamans as we listen to New Riders of the Purple Sage singing “I Don’t Need No Doctor (because I’ve lost the will to live).”

We hide the bottles around the unit, behind a sofa cushion or in a grandma’s knitting bag. The wine tastes like soap but I’m happy to be included. Without the Druggies, my companions would be the ladies who recline in wicker armchairs as if they were at an exclusive resort soaking up the sun. They liked to pretend that they are not parked in a row, abandoned in a mental hospital corridor.

The boredom is insidious. I’m alert for any sign that heralds a change. New admissions get my full attention because they promise relief, or at least entertainment. There’s a subtle hum of activity as the aides prepare the room and the nurses bustle about with pinched lips, feeling sorry for themselves, regretting that it had to happen on their shift.

* * *

Nora is carried in on a stretcher, bandages lining both forearms. Days later, she emerges from her room wearing pearls and a twin set, ankle socks with loafers. Her style and maiden-lady manners make her seem older than the college student she is. She reads the New Yorker cover-to-cover every week then gives me the magazines. Her room has become a psychiatric salon where she applauds my solitary lines of poetry. Her favourite is for a friggin’ nickel, I’d buy a Jewish dill pickle.

Holly is a fragile blond who refuses to eat and will not speak. I talk to her nonstop while we pace the halls.

“She’s catatonic. You’re wasting your sweet time,” the Druggies tell me.

“She’s protesting,” I reply. “She knows exactly what she’s doing.”

When I finally succeed in coaxing a smile from Holly, she understands that I will keep her secret.

On two occasions, they snake a tube up Holly’s nose and down her throat.

I watch this torturous scene from the partially opened door of the treatment room.

Before the start of the third treatment, she shouts her first words, “OK! I’ll eat!”

* * *

The Druggies launch a campaign to be taken swimming, having seen the same brochure my father admired. Every day they lead us in a chant, “Take the loonies swimming! Take the loonies swimming!” All the patients join in, even the ones who have no idea what we are demanding.

We keep the chorus humming for weeks until the loonies are finally taken swimming. Some of us don’t have the regulation blue tank suits. We improvise with the yellowing lingerie that hangs abandoned in the washroom. We go to the pool through underground tunnels between the wings of the hospital. None of us loonies are allowed outside, above the ground. We are considered security risks and do not have grounds passes.

The tunnels smell of dank earth and steam heat. Exposed pipes line the low ceilings. I’m amazed at the sheer number of food, laundry and cleaning staff who swarm in this primeval underground hive. They speak a patois I can’t quite understand but their words are musical, like a song from a tropical island.

For me, the chanting was more fun than the actual dip into the icy water. The Druggies, on the other hand, do belly flops then splash each other like dolphins in the tiny pool. They frolic as if they are at summer camp. I realize, along with the rest of the loonies, that the power scales have tipped.

Once spring arrives, we’re allowed outside in a courtyard enclosed by high brick walls. After being locked inside for five months, this tiny patch of walled-in dirt allows me my first sniff of freedom. The breeze is intoxicating; I sit on a bench and tilt my face up to the light, like a sunflower. Later I join the rest of the girls as we circle the perimeter of the courtyard. One of the Druggies yells “clockwise” and later, when she announces “about-face,” we turn in unison like synchronized swimmers. We refuse to come inside. Our demand to stay out past dark is granted.

We attend metal and leather-work classes once a week, travelling again through the underground tunnels. The therapist in charge of the leatherwork class has a port-wine stain on the left side of her face, from her cheekbone to her chin, the same shade as the maroon dye I use to colour a leather wrist band. I wonder about the mark; it looks like someone tossed acid at her face. I still worry about what I might have done during the time I can’t remember. If I could arrive at this place with no memory of the journey, it’s possible that I may have hurled the acid, or done something worse to warrant being locked up.

“You look like a girl who loves to ride horses,” the metal shop supervisor singles me out.

I wonder what it is about me that makes him guess right as I polish a silver ring.

Later, I stare at my reflection in what passes for a mirror, a piece of reflective paper taped to the washroom wall. My hair vines past my shoulders, thick, wavy, and matted, like a horse’s tail. Somewhere there is a girl who looks a lot like me, galloping away on a taffy-coloured horse.

* * *

When the medication renders me passive and obedient, I’m promoted to a co-ed unit where I earn a grounds pass. The sharps are not counted after every meal.

“You are on your way to recovery,” I’m told.

I am more disconnected than ever. Lethargy and apathy take their toll.

The new ward could have passed for a college dorm; the essential missing ingredient is laughter. Medication fogs any chance of joy. The halls are deadly quiet.

I’m permitted to walk outside on the hospital grounds, without an escort. As a model mental patient, soon I’m ready to be released.

I’m instructed to take Thorazine for the rest of my life. My therapist suggests that a job in a fast-food restaurant is a realistic career goal.

“I’d like to work in a bookstore,” I tell him.

“Everyone would like a job in a bookstore. It’s unlikely that will happen.” He kills my dream with his words.

I won’t live a half-life working in a McDonald’s while taking debilitating drugs for the rest of my life. Suicide seems like a better solution than this blueprint, though I’ve learned to keep such thoughts secret.

My family has confidence in the documents that testify to my sanity. After all, I’ve been deemed sane by the system, an endorsement few can claim. My old bedroom is freshly whitewashed and sports a new yellow bedspread. The past is not discussed. At a family gathering, I’m referred to as “the one that was away.”

My new psychiatrist gestures to three black binders on his desk: my medical records. His face is kind, but he’s clearly disturbed by my history.

“You were never diagnosed with any mental illness,” he tells me. “Nobody knew what to do with you. They had you on so many different drugs and you had an extreme reaction. Then they sent you away.

He advises, “Stop taking the Thorazine. You don’t need it. Think about moving far away from your family. Maybe California would be a good place for you.”

I hide my almost full bottle of Thorazine in my bottom dresser drawer, under some sweatshirts. I write a poem about the apricot-coloured light I imagine exists in California.

* * *

After I find a job in a bookstore, I move away from my family. One Sunday night when I walk to the corner store to buy a pack of cigarettes, I’m surprised by the sound of my voice because I haven’t heard it all weekend. I’m careful, so very careful, not to draw attention to myself. I’m an actress playing the role of a lifetime where I must pass as normal.

If the system gets hold of me again, I have the pills, more than enough to do the job.

I line them up on my kitchen table, feeling their power as they snake around the perimeter, like soldiers preparing for battle.

A year later, I move to California. The light is the exact shade of apricot I imagined.

Marcie I appreciate your article because it doesn’t advocate Therapy or Recovery, or otherwise promote the Mental Health System.

Those drugs and the hospitals should not exist. The people who distribute the drugs and run the hospitals all hold government issued medical licenses. And this is what puts it squarely within Nuremburg Precedent for Crimes Against Humanity. These people should be prosecuted in the International Court and they should receive the death penalty.

Joshua

Report comment

Beautifully written. Very powerful. Thank you.

Report comment

Thank you for reading my story. I appreciate your comment!

Report comment

You are an excellent writer. I think what struck me the most is when you went to the psychiatrist who wisely saw that you had no mental illness diagnosis, it was the psych drugs and you needed to stop taking the thorazine and move to California away from your family. Whoa! What a rare psychiatrist! And, it seems you are still in California and happy. I don’t know, but sadly, there are some who are convinced they have a “mental illness” maybe by the mental health system, maybe by family, or who knows… and then almost get stuck in it. I would say many times there are other issues. It is just much easier to call the person “crazy” and subject them to the darker side of the system, when all they really needed is affirmation and love that it is just alright to be who you are even it is not “like us” or whatever. In my personal opinion, I think for some, the concept of ” being neurodivergent” helps. But of course, for others it does not. No matter what, the uneven and even dangerous treatment, including the psychiatric drugs of the alleged mentally ill is very disconcerting. I was in a “mental hospital” for about eleven days about nine years ago. It was cleaner and nicer in appearance, but it was alienating. From all reports, most who went there came out worse than when they went in…I think that included me. Some people were quite angry when they left there and just considered a waste of time. I haven’t got an any real answers, except kindness, understanding, respect and dignity for everyone no matter who they are—goes a long way… Additionally, wishing ill on those who hurt you is sometimes understandable, but as they be careful what you wish for… It may come back to haunt you in ways you never thought of… As for your story, it is wonderful, informative, and compelling. Thank you.

Report comment

Thank you for reading and commenting. I totally understand about leaving such “hospitals” sicker than when we arrived.

Hope your life continues with the kindness of others and understanding.

Best to you,

Marcie

Report comment

A “Retreat for the Insane.” Oh, how I wish there were such a place! I’d move in immediately. Thanks for this essay, Marcie. I look forward to finding more of your writing online.

Report comment

Thanks for reading and commenting Francesca!

Marcie

Report comment

Unable – and unwilling – to tell the difference between ‘sane’ and ‘insane’, or between help and harm, or support and blame. The narrative is vaguely and superficially built not on facts, but on what someone else said or thought or claimed, or on another unvetted narrative in a medical or court record, or a misinterpretation of one of those things that happened somewhere along the way, or nothing at all except status as “one of them”, however that came to be. Disease is defined and demonstrated in part or in whole by refutation or ‘refusal’; progress is defined as validation of what is said and done. But there is no end, not because ‘recovery’ isn’t possible, but because it is not compatible with the narrative and the model and with the notion that anyone within or any part of the system could be flawed in any way, because to consider the possibility has dangerous implications, personally and professionally, even legally.

The system isn’t ‘imperfect’; it’s assertively contemptuous of reality and of people. It’s dishonest and upheld by fragile, myopic sycophancy. Because it’s fragile, it’s hostile and defensive. So these stories develop along similar lines even when the details and circumstances would otherwise be wildly different. It’s always the same at the end of the day.

Report comment

Dear Marcie,

Thank you for writing this so candidly. I was labeled as a “troubled” and “mentally ill” kid, which led to a strikingly similar experience during my teen years. Since I am less than a year out of the system, it can be hard to trust that there’s a worthwhile future ahead of me. Like you described feeling at my age, my personality is still caught up in evading DSM-style judgement, but I am determined to be free. It gives me hope to see that you were able to move on, so much so that you could write this as a retrospective piece. Was there anything in particular that helped you shake the feeling of being a loony incognito?

Courtney

Report comment

Hi Courtney!

It took me fifty years to be able to write and publish my story. The shame was so deep- I never told any of my friends until I got cancer 20 years ago. When I was first diagnosed, my thoughts were: ” I have survived something way worse than cancer. So I can do this !” It helped me to realize the shame was only there because I allowed it to be. All my friends shrugged their shoulders and moved on from my “confession” and stood by me.

Hope this might help you a tiny bit to find your own way.

The best hope to you,

Marcie

Report comment

This was REALLY well-written. Have you written any larger pieces about your psychiatric experience? Please let me know; I would love to read them. I have been struggling for years now to write a memoir about my own psychiatric experience, which took up my entire childhood from ages six to seventeen. I am much older now, age 85 to be exact, but when I think of what was done to me then, it brings back the feeling from then that I am a subhuman mental case. Not very “therapeutic”, eh?

Report comment

Hello Marcie, Thank you for sharing your compelling story. I have seen some of the best and worst of psychiatry. As a co-therapist in a therapy group I witnessed a psychiatrist challenge a participant to follow through on his threat to commit suicide. I was young and a new hire and powerless to confront the Director of the Dept. I was appalled, and then tormented when the young man followed through. I have also been a witness to kindness and competence.

When I moved from Iowa to AZ. I was shocked that most mental health hospital treatment was mostly just “milieu”, a kind of resting place. But, it is such a lost opportunity to do serious work. So much has changed in the field over time. One change is the loss of importance in understanding Family Dynamics. Of course this is what makes most people “crazy”. That lack of understanding has lead to over-medicalizing mental health.

Would you accept a small gift? Your writing is surely an advocacy for improving the mental health of others. I hope to do the same. My not-for-profit project allows people to do their own therapy. It often shocks people with the amount of help it provides. If you google my name, or the program, Se-REM, you can read all about it. I give away the link to download it as often as I am asked.

Take care, David Busch, LCSW (retired trauma therapist).

Report comment

” a rebellious, promiscuous, pot-smoking teenager who didn’t know how to lie.” Sounds pretty normal to me! The beat poets made careers out of such lives, although it m7st he said, they were mainly men and therefore given more leeway than women.

However: “Self-care is how you take your power back,” is patronizing rubbish. The institutions have turned from tranquilizer dominated prisons to tranquilizer dominated prisons run by the soft police.

Report comment

This system must be abolished. Innocent people’s lives are being ruined for the reason that we think we can “medicate” life problems away. I admire your intelligent narrative and hope your will continue to write. I am working on the seemingly insurmountable conundrums in today’s world, especially in the area of so called “mental health”.

Thank you.

Report comment