It’s been a polarizing year for mental health. Back in March, psychiatry finally annexed grief. After years of trying, Prolonged Grief Disorder is now an official mental illness. Just a few months later, though, Dr. Joanna Moncrieff and colleagues refuted the chemical imbalance theory of depression.

Whichever side you come down on, then, the ancient guidebook translated as How to Grieve has suddenly taken on a new urgency.

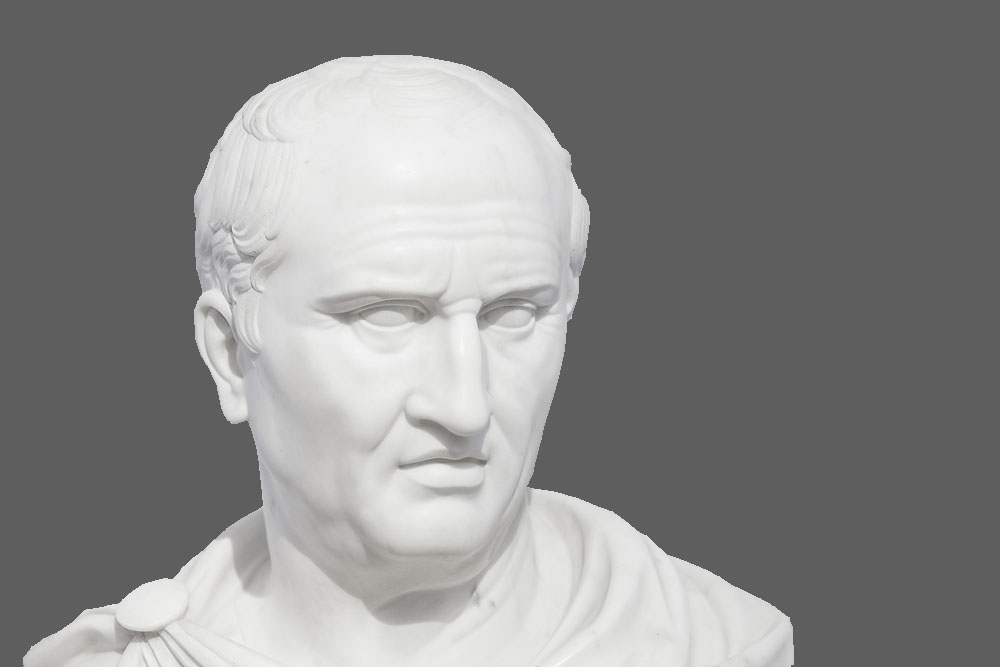

How to Grieve is a Renaissance recreation of a lost text from ancient Rome by Cicero, and it’s meant for a wide audience. It’s packed with talk-therapy strategies for coping with grief. And since readers new to ancient philosophy may find the style of argument surprising, I’d like to help them make sense of it.

Two thousand years ago, Marcus Tullius Cicero was “Consul” (essentially, co-president) of ancient Rome. He was also a doting father. In 45 BCE, his only daughter, Tullia, died from complications of childbirth. She was only 32. Cicero fell to pieces, and in a desperate attempt to recover, he holed up in his library and wrote himself the world’s first guide to talking one’s way out of grief.

Talk yourself out of grief? Reason yourself out of depression? That sounds impossible, but Cicero says it worked—and that it can work for us, too. And since Cicero wrote one of the world’s first books on mental health, it’s worth paying attention to what he says.

Cicero’s basic idea is to equate grief with feeling sorry for yourself. Or rather, with having unrealistic expectations of the world. This may sound bracing, but many people believe it—not least psychiatrists themselves.

I say this because, to its credit, psychiatry currently recommends cognitive behavioral therapy instead of drugs to cope with grief: “There are currently no medications to treat specific symptoms of grief. […] Treatments using elements of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) have been found to be effective in reducing symptoms.”

CBT is a form of talk therapy. It’s based on the idea that our psychological problems are based on faulty or counterproductive ways of thinking. We can’t change stresses and disappointments themselves, it says, but if we can just change the way we think about those stresses and disappointments, we’ll be happier people.

The idea that we can cope with grief by bringing our expectations in line with reality is an old one. It’s a core insight of Stoicism, one of the two main denominations of “philosophy” (secular religions) in ancient Rome. In fact, it’s crucial to realize that Stoicism isn’t like CBT. Stoicism is CBT, though many don’t realize it.

Stoicism is all the rage these days, with websites and thought leaders all around us. In ancient Rome, Stoicism was promoted in pop-psychology books. They were written in simple language and with simple examples that anybody can understand. For instance, when one Stoic—a man named Epictetus—wants to tells us we need to get our priorities straight, watch how he does it:

When it comes to something appealing or useful to you, or something you cherish, remember to tell yourself what sort of thing it is. Start with the smallest things and work your way up. For instance, let’s say you cherish a pot. Say to yourself, “It is a pot that I cherish.” That way, when it breaks, you won’t be upset. When you kiss your child or wife, tell yourself, “It is a human being that I am kissing.” That way, if one of them dies, you won’t be upset.

In my experience, the jarring switch from a pot to a child or wife tends to freak college students out. Mature students, though, immediately see the point. Which is this: Epictetus is saying, let’s make the question real. Don’t waste time on baby steps. Take it to the extreme.

This style of argument isn’t “reductio ad absurdum”; it’s more like “reductio ad extremum.” It reduces a question to the most extreme, but realistic, form you’ll probably face in real life.

This is how ancient philosophers argue. They waste no time on easier cases. Instead, they go straight to the endpoints.

The great rival of Stoicism in ancient Rome is called Epicureanism, and it had its own talk therapies. Unlike Stoicism, which advocated morality as the greatest thing in the world, Epicureanism advocated pleasure as the value we hold most dear. No matter what we tell ourselves, Epicureanism says, at the end of the day, physical pleasure is superior to virtue. Survival trumps idealism.

To prove the point, a philosopher named Lucretius presents the horrifying case of a drowning man:

It is comforting, when winds are whipping up the waters of the vast sea, to watch from land the severe trials of another person: not that anyone’s distress is a cause of agreeable pleasure; but it is comforting to see from what troubles you yourself are exempt.

Be honest, he says: aren’t you glad the guy sinking out there isn’t you? If not, would you trade places with him?

Again, to call that “comforting” is an extreme case. But if you answer the question honestly, then you have a good idea of how you’ll act in easier cases.

In addition to “reductio ad extremum,” ancient writers love to cite anecdotes or famous examples to make their points. For them, a single example proves what’s humanly possible—which doesn’t mean it’s easy, just possible.

Seneca, a Stoic, combines the two styles—reductio ad extremum, plus an anecdote—in one memorable case in a wonderful treatise titled On Anger. He wants to prove that no matter how impossible it may feel, it is possible to stifle anger. In it, a father named Prexaspes has to restrain his rage as he watches a tyrant shoot his son:

King Cambyses [of Persia] was overly given to drinking wine, and Prexaspes, one of his inner circle, warned him to drink less, saying that drunkenness was shameful in a monarch, a man observed and heard by all. Cambyses replied, “Just so you’ll know how I never lose control, I’ll prove right now that my eyes and hands are quite capable, even after my wine.” Then he drank more freely than at other times, from fuller goblets, and when he was sodden and wine-soaked, he ordered the son of Prexaspes, his chastiser, to go just outside the door and stand there with his left hand held above his head. Then he bent his bow and shot the boy right through the heart—it was where he had said he was aiming—and, having had his chest cut open, showed the barb stuck in the heart itself. He looked back at the boy’s father and asked him whether or not he had a sure enough hand; Prexaspes said that Apollo himself could not have shot more true. May the gods blast him, a slave in his mind more than in his status! He praised a deed that was too much even to watch. . . . We’ll examine elsewhere how the father ought to have behaved, as he stood over his son’s corpse and the murder he had both witnessed and caused. What’s clear in the present context is that anger can be contained.

If that man could restrain his anger as he watched a monster murder his own son—because he had no choice—then surely it’s possible for us to restrain our anger in more trivial cases, like getting cut off in the parking lot.

It’s like winning the Olympics or losing weight. Lord knows neither is easy, but when we see someone do it, we’re forced to admit it can be done. (This is the idea underlying the mantra “If I could do it, so can you!”)

In How to Grieve, Cicero draws on these extreme case studies over and over to show us that it’s possible to overcome grief. (In fact, he cites the very same case of Prexaspes.) If people before us survived horrifying losses, he insists, then we can, too. Those anecdotes can become role models for us.

Nowadays, many of us look to celebrities or athletes for our role models. Not so long ago, though, many knew the case of Theodore Roosevelt, the future U.S. president whose wife and mother died on the same day in 1884. The 25-year-old Roosevelt fell to pieces—he moved to the Dakotas for two years—before eventually finding his way back and becoming famous for his “stoicism.”

In the same way, Cicero cites many examples of famous men and women who survived heartbreaking tragedies—and who prove, therefore, that heartbreaking tragedies can be survived. For example, Cicero quotes the case of Pericles:

Pericles, says history, lost two sons—extraordinary young men—in four days. He was so strong and unwavering in his grief, though, that he didn’t change a single thing in his conduct or appearance. On the contrary, he kept to his schedule of public meetings and never removed the garland from his head.

He also cites the case of Lucius Aemilius Paullus:

What case is more famous or celebrated than Lucius Aemilius Paullus? He lost two sons just days apart with almost no sign of grief. Rather, in the speech he gave before the people reporting on his accomplishments, he thanked the immortal gods for bringing down upon himself whatever adversity was threatening the Roman people!

On the strength of these examples, Cicero insists that we must get realistic about the world before tragedy strikes. And because tragedy is inevitable, the time to start is now. As he puts it,

I hope my attempt can show others in my situation how to endure sudden losses with forbearing, since the more often tragedy strikes, the more intimately human we must think tragedies are. We must think of them as virtually congenital, bound up with human nature, and hence, for that reason, easier to endure. I mean, if you accept and pride yourself on being human, then how could you possibly reject and refuse a chief condition of being human?

Birth is a death sentence. Nobody likes it. But that’s life. And once we finally realize that, and once we’ve seen that others have survived grief, then we have to find it within ourselves to do so, too. Because moping around forever, says Cicero, is tantamount to a prison sentence:

As a slave of grief, you’re physically impaired and you’re suffering unimaginable heartache. You can’t enjoy friends, serve your country, manage your private life, advise the public. You have freedom, but the most oppressive kind: you answer to no one, yet don’t govern yourself.

Grief may be agonizing, but we can recover. Cicero wrote his book to help us do that. Once you grasp its argumentative style, it just may help you or a loved one, too.

Thank You Dr Fontaine,

I replaced Long Acting Neuroleptic Depot Injections with the types of Psychological Principles that you describe in your article.

The CBT term “Catastrophisation” is a brilliant expression because it humanizes distress in a way that most people can identify with. I suffered from a lot of “Catastrophisation” in my attempts to withdraw from psychiatric drugs.

The CBT term “Emotional Reasoning” is also very pertinent, as this is exactly what I do when I am Catastrophic. If I can avoid Reasoning Emotionally I can eventually see things in a Neutral or Non Distressed manner. Recognising this, is how I managed to withdraw from my “Neuroleptic Depot Injection”!

Report comment

Thank you for your attention to this topic. I offer my thoughts about “GRIEF’ free of influence from experts on the topic. The pathologization of grief is a strategic tool to bury the sins of oppressors and to facilitate the rewriting of history and tryanny.

Report comment

People who want to be humble and sympathetic to us will refer to the grief that we must be feeling. I wonder why they only talk about grief. I wonder if they presume that we are just “hung up” and can’t get over our daughter’s death. I don’t want to discuss grief with them. I want to generate interest in the injustice that directed cruel treatment of our daughter.

Report comment

Ok, I just need to think more about making transitions in conversation to the real issue in a positive way, which is what we’ve been doing. That’s the necessary work.

Report comment

As a narrative therapist and a person whose family carries cancer vulnerabilities, I have found respect for the process. Culturally, Native America, Mexico, Buddhist cultures have much more to offer than the US on this subject. Cicero would not be my go to source for understanding of the Bardo.

Report comment