After we published our MIA Report on the STAR*D Scandal and set up a petition urging the American Journal of Psychiatry to retract the 2006 paper that told of the summary STAR*D results, I figured that Awais Aftab would respond with a post on his Substack blog. I actually do genuinely appreciate that he engages with pieces we publish, because such back and forth represents a type of debate, and it then becomes easier for the public to see the merits of the differing “presentations of fact.”

Aftab has presented himself as a psychiatrist who is open to criticisms of psychiatry and, at the same time, as a defender of the profession. He has gained public stature in that regard, as the go-to person for responding to criticisms of the profession.

In this case, Aftab presents his post as a response to Pigott’s re-analysis of the STAR*D results. While he doesn’t refer directly to MIA’s report on the STAR*D scandal, it is clear that he has read it and that this is what prompted his post. He closes his piece with an accusation that MIA and I have misled the public with our reporting on the STAR*D study, which is the reason for this blog.

Our MIA Report tells of the “STAR*D Scandal.” The scandal, however, is not simply that the STAR*D investigators violated the protocol in ways that inflated the remission rate. The scandal is that the NIMH and the profession promoted the fabricated 67% remission rate to the public as evidence of the effectiveness of antidepressants, and did so even after Pigott and colleagues published a paper in 2010 that told of how it was an inflated result born of research misconduct. As such, the MIA Report is an account of a profession’s collective failure to inform the public of the true results of this study.

What is of interest here, in this “back and forth,” is to first see whether Aftab’s post tells of the larger scandal, and second to see whether his accusation that MIA has misled the public has merit. And if it doesn’t, it can be seen as adding a new dollop of deceit into the STAR*D scandal.

Aftab’s Post

In the first part of his post, Aftab writes of how Pigott’s RIAT reanalysis of patient level-data in the STAR*D trial reveals that the true remission rate during the acute phase of the study was 35% instead of the reported 67%. Aftab acknowledges that this difference is concerning.

“There are two kinds of discussions we can have about this STAR*D reanalysis. The first is focused on the deviations from the original protocol and the lack of transparency about the significance of these deviations in scientific reporting. This is an important story to tell, and I’m glad that it has been told. (I am doubtful that it constitutes scientific misconduct or fraud, as some critics have alleged, but the lack of transparency is certainly concerning and difficult to defend.)”

If you deconstruct that paragraph, you can see that it subtly functions in three ways:

- He is presenting himself as one who cares about scientific integrity.

- While acknowledging that mistakes were made, he is also absolving—at least partially so—the STAR*D investigators of scientific misconduct. The problem with the STAR*D report wasn’t so much that the investigators violated the protocol in numerous ways that inflated the remission rate, but rather a “lack of transparency” in their reports about these deviations from the protocol.

- He is setting up a case that unnamed critics (e.g. MIA) are making “allegations” that go too far.

You might say there are three characters in that paragraph: the virtuous (him), the flawed (the STAR*D investigators), and the morally suspect (the critics.)

He then turns to the second “kind of discussion” that can be had, which is whether there was any clinical harm done by the false report of a 67% remission rate. He writes:

“How does this (reanalysis) change what we now know about antidepressants? My impression is . . . not much. We have more treatment options now than existed when STAR*D was planned and executed. We have a more somber assessment of the efficacy of traditional antidepressants in general, and partly as a result of STAR*D itself, attention has shifted onto ‘treatment-resistant’ depression. In this sense, the re-analysis, as important as it is for the integrity of the scientific record, has little impact on clinical decision-making and serves more as a cautionary tale of how yet another beloved research statistic doesn’t stand up to rigorous scrutiny.”

In this passage, Aftab is distancing today’s psychiatry from any connection to the STAR*D misdeeds. Indeed, he is using the STAR*D study as a foil to give today’s psychiatry a pat on the back. The field, it seems, has continued to hone its knowledge of the effectiveness of antidepressants and broadened its tools for treating depression. The march of progress in psychiatry continues, with STAR*D a distant blip in the past.

In short, it’s not a piece that will ruffle any feathers of his peers. There is no discussion of the larger scandal presented in the MIA Report, which is that the profession never sought to correct the scientific record after Pigott detailed the protocol violations that produced the inflated remission rate, and that it continued to peddle the 67% effectiveness rate to the public even after that research misconduct became known. Nor is there any discussion of whether the 2006 article published in the American Journal of Psychiatry that told of the 67% remission rate should be retracted.

That’s the ethical challenge presented to psychiatry today: should that 2006 article be retracted? Aftab’s post dodges that question. Yet, if the article is not retracted, and the public is not informed that the 67% remission rate was a result born of research misconduct, then psychiatry’s betrayal of the public continues. Aftab may dismiss the study as “two decades old,” but media still cite it today as evidence of the effectiveness of antidepressants.

And Now on to Whitaker: There Is Where You Can Find Real Deceit!

The second part of the STAR*D study consisted of a year-long maintenance trial, which focused on whether patients who had remitted could stay well and in clinical care during that extended period. However, the STAR*D investigators never reported those findings with any clarity, and it wasn’t until Pigott and colleagues published their 2010 paper that this bottom-line outcome became known. Although Aftab didn’t discuss this aspect of the STAR*D scandal, as he closed his piece he cited our reporting of the one-year outcomes as “misleading” and evidence of our “being deceptive.”

Here is what he wrote:

“In addition to the 67% figure, another misleading statistic is the 3% stay-well rate commonly cited in critical spaces such as Mad in America. Robert Whitaker, for example, frequently points out that only 3% of the patients in STAR*D remitted and were still well at the end of the one year of follow-up. This is misleading because, due to massive drop-outs, this doesn’t translate into an assertion that only 3% of patients with depression remain well in the year after treatment. According to the 2006 summary article, there were only 132 patients in the 9-12 months naturalistic follow-up time period. The extremely high rate of drop-outs essentially renders the 3% figure meaningless, and anyone who cites it with a straight face is being deceptive.”

Thus, Aftab is making two claims to his readers: First, that as I have reported on the one-year outcomes, I have failed to mention the dropouts. Second, that I assert that the study tells of how, in the real world, “only 3% of patients with depression remain well in the year after treatment.”

The simple way to review this charge is to revisit our recent MIA Report, which Aftab had read. There we can see, with great clarity, whether Aftab’s charge has merit, or whether he has told what might be described, if I let my temper get the best of me, as a “big fat lie.”

Our MIA Report

In the opening paragraphs of our report, I noted how Ed Pigott and colleagues, in their 2010 paper, had finally made sense of a graphic in the STAR*D summary paper that told of the outcomes at the end of the one-year follow-up. I wrote that Pigott and colleagues had found that “only 3% of the 4,041 patients who entered the trial had remitted and then stayed well and in the trial to its end.” (Emphasis added.)

The key part of that sentence, for purposes of this piece, is the phrase “and in the trial.” That is the part of the sentence that tells of how all the others in the trial either never remitted, remitted and then relapsed, or dropped out. This sentence is simply an accurate description of the trial results, as summed up by Pigott. What Aftab did, however, was omit the part of the sentence that includes “in the trial” and then, having omitted those words, accuse me of not mentioning the dropouts.

His second assertion is that I write about this one-year outcome as evidence of the long-term stay-well rate for patients treated with antidepressants in general. However, as can be seen in the MIA Report, my reporting on the STAR*D study tells of what the results were in this particular study, as reported by Pigott and colleagues. And that is this: Of the 4,041 patients who entered the study, there were only 108 who remitted and then stayed well and in the trial to its end. The point of my reporting is that the STAR*D investigators hid this poor one-year result, and how it stands in stark contrast to the 67% remission rate peddled to the public.

Thus, my reporting of this one-year outcome is focused on how the the STAR*D investigators and the NIMH—and by extension psychiatry as a profession—misled the public about the findings in this particular study. I am reporting on the scandal, and not on what evidence may exist in the research literature on long-term stay-well rates for patients treated with antidepressants.

However, that isn’t even the most telling refutation of Aftab’s accusation. What is most damning is that in our recent report we provided an exact count of the number who relapsed and of the number who dropped out during the maintenance phase of the trial, and that this was the first time that this exact count had ever been published. Thus, rather than fail in some way to accurately report on the results in the maintenance phase, we filled in the data that the STAR*D investigators had hidden in their summary report.

Here is the complete section from our recent MIA Report on the one-year outcomes:

One-year outcomes

There were 1,518 who entered the follow-up trial in remission. The protocol called for regular clinical visits during the year, during which their symptoms would be evaluated using QIDS-SR. Clinicians would use these self-report scores to guide their clinical care: they could change medication dosages, prescribe other medications, and recommend psychotherapy to help the patients stay well. Every three months their symptoms would be evaluated using the HAM-D. Relapse was defined as a HAM-D score of 14 or higher.

This was the larger question posed by STAR*D: What percentage of depressed patients treated with antidepressants remitted and stayed well? Yet, in the discussion section of their final report, the STAR*D investigators devoted only two short paragraphs to the one-year results. They did not report relapse rates, but rather simply wrote that “relapse rates were higher for those who entered follow-up after more treatment steps.”

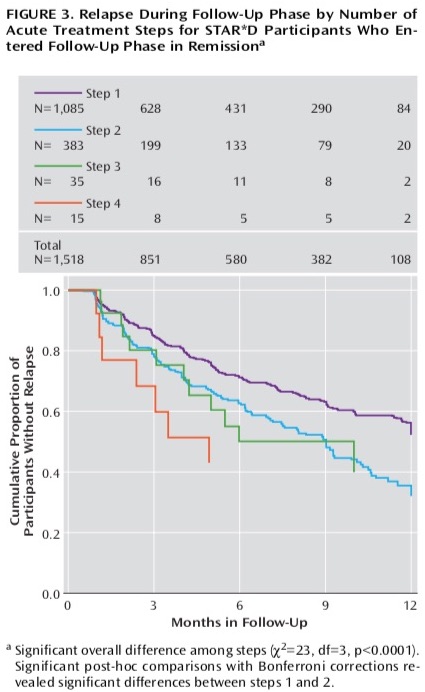

Table five in the report provided the relapse rate statistics: 33.5% for the step 1 remitters, 47.4% for step 2, 42.9% for step 3, and 50% for step 4. At least at first glance, this suggested that perhaps 60% of the 1,518 patients had stayed well during the one-year maintenance study.

However, missing from the discussion and the relapse table was any mention of dropouts. How many had stayed in the trial to the one-year end?

There was a second graphic that appeared to provide information regarding “relapse rates” over the 12-month period. But without an explanation for the data in the graphic, it was impossible to decipher its meaning. Here it is:

Once Pigott launched his sleuthing efforts, he was able to figure it out. The numbers in the top part of the graphic told of how many remitted patients remained well and in the trial at three months, six months, nine months and one year. In other words, the top part of this graphic provided a running account of relapses plus dropouts. This is where the dropouts lay hidden.

Before Pigott published his finding, he checked with the STAR*D biostatistician, Stephen Wisniewski, to make sure he was reading the graphic right. Wisniewski replied: “Two things can happen during the course of follow-up that can impact on the size of the sample being analyzed. One is the event, in this case, relapse, occurring. The other is drop out. So the N’s over time represent that size of the population that is remaining in the sample (that is, has not dropped out or relapsed at an earlier time).”

Here, then, was the one-year result that the STAR*D investigators declined to make clear. Of the 1,518 remitted patients who entered the follow-up, only 108 patients remained well and in the trial at the end of 12 months. The other 1,410 patients either relapsed (439) or dropped out (971).

Pigott and colleagues, when they published their 2010 deconstruction of the STAR*D study, summed up the one-year results in this way: Of 4,041 patients who entered the study, only 108 remitted and then stayed well and in the study to its one-year end. That was a documented get-well and stay-well rate of 3%.

To summarize, this section of our report identifies the precise number of dropouts during the one-year follow-up study, information that the STAR*D investigators had hidden, and for the first time ever, reported on the precise number of relapses and dropouts in the maintenance phase. Yet, Awais Aftab, in his post on the STAR*D scandals, accuses me of misleading readers for failing to note the high dropout rate.

In making this accusation, Aftab exemplifies the very failure that is at the heart of the STAR*D scandal. The scandal is that psychiatry cannot be trusted to provide an honest accounting to the public of its research findings, and here Aftab demonstrates this same dishonesty. I provide, for the first time, an exact account of the outcomes for the 1,518 patients who entered the maintenance trial in remission, and yet he accuses me of misleading the public, and—with his “straight face” remark—suggests I am doing so with an “intent to deceive.”

Hence the title of this blog. The STAR*D scandal is about how psychiatry peddled a fabricated result to the public, and now Aftab, in his latest post, has added a whopper of his own to the STAR*D story.

It never ends does it?

Report comment

Someday it will end.

Report comment

Aftab is clearly well-schooled in the art of obfuscation, which one has to admit he practices quite well. But his unsurprising attempts to discredit Mr. Whitaker and MIA in his propaganda piece (blog) only reveal how threatened he truly feels.

Report comment

With all respect and admiration for Mr. Robert Whittaker:

I think you are reading too much into the response. I have not read Mr. Aftab’s piece since it’s behind a paywall.

But what I read just in the paragraphs about deviations to me does not support your 3 points interpretation. Particularly not your “You might say there are three characters in that paragraph: the virtuous (him), the flawed (the STAR*D investigators), and the morally suspect (the critics.)”

As intermezzo: “We have a more somber assessment of the efficacy of traditional antidepressants in general, and partly as a result of STAR*D itself, attention has shifted onto ‘treatment-resistant’ depression.” seems to me an admision of guilt if the real “result” of STAR*D was known outside the published record. Insider’s knowledge not made public until Mr. Piggot and You at al. The unveiling all over again.

Read together the paragraph of Mr Aftab where he admits it has little impact, not had, with the admission of deviations, not constituting, per the narrative, misconduct or fraud, with recognizing the importance of this reanalysis is, I guess as good as anyone is going to get from psychiatry. Particularly when it presents implicitly the STAR*D as a cautionary tale.

And oddly, it praises rigorous scrutiny, which by implication is putting in good light the reanalysis.

I have another interpretation for the parapgraph “The extremely high rate of drop-outs essentially renders the 3% figure meaningless, and any who cites it with a straight face is being deceptive.”

To me it means, hyperbolically: Don’t bother, the STAR*D won’t give you any number worth reporting. It’s an awefull statement, but it’s very classy, I got to admit.

Thanks again, forever gratefull, I had a good laugh at the back and forth, but it seems difficult to keep commenting beyond my personal situation. And apparently is not just me.

Thanks again. Good luck.

Report comment

A propos of some of the rest of MIA and its movement:

from:

https://www.eluniversal.com.mx/opinion/jose-narro-robles/carpizo-mexico-y-la-moral-publica/

“It should not be accepted, that lying, simulation and illegality to be justified. Nor attempts at division into two camps, and that within those two camps there were devices and arguments to condemn or apologize such acts, and that in order to achieve that, what matters, what counts, is the convinience of any faction, and not the act being done.”

My translation.

“No debería aceptarse que la mentira, la simulación y la ilegalidad se justifiquen. Que en los dos bandos en los que nos quieren dividir, se tengan medidas y argumentos para condenar o disculpar actos semejantes y que para hacerlo lo que cuente es la conveniencia de la facción de que se trate y no del acto que los ocupe.”

Writen originaly by José Narro Robles, physician, exRector of the biggest public University in Mexico and I think latin america, former director of Health at national level, former president of the National Academy of Medicine in Mexico. Among others.

Narro was writting a propos of Jorge Carpizo, first ombudsman of the National Comission of Human Rights in Mexico, and the over 20yrs problems, and the analysis of those problems in Mexico done by Carpizo.

Which seems a relevant quote to me, because your post, this post, and comments at MIA inspired me to do it.

Report comment

I read the same rhetorical constructions in Aftab’s blog piece as Bob Whitaker does.

Report comment

There’s another logical conclusion that’s not gonna be explored here. Except by me….

Aftab is clearly in thrall to the Gods of psychiatry & psych drugs. Given that psychiatry is a pseudoscience & drug racket, it’s inevitable that Aftab would only, indeed CAN ONLY, recite the psych’s catechism. Parrot it’s high priests. Aftab TRULY BELIEVES the non-sense he’s spouting.

Given that he truly believes, he will of course logically pretzel ANY critical comment into some other sematic form. Aftab’s greatest feat here, is elevating the already lofty Robert Whitaker.

Robert “Psych Slayer” Whitaker. I hope my humor doesn’t get my comment moderated away….

Report comment

Not an act of agression. Yes, you might be in the minority.

But being in the minority, like me, suggests a simpe way to clarify, who is who on the debate:

Just let’s ask Mr. Aftab, that since he seems to admit the reanalysis is useful, and that the 3% figure is wrong, then: “Mr. Aftab what figure do you think the media, the New York Times, etc, should quote as TRUE figure from the STAR*D sutdy?”

Now, that would make Mr. Aftab squirm, and show what he really meant in the quoted passages and the context provided by Mr. Whitaker.

And it could decide the implicit question: Was the media deceived? bamboozled?. Regardless if it is important or not to current psychiatrical practice, if they moved on…

As for Mr. Aftab reading MIA and “backforthing” with it, I have another interpretation: If I were a practitioner and faced enough MIA rhetoric and quotes, instead of addressing each in the consulting office, I would just write in my blog, and direct MY patients to read it, instead or to complement MIA. No mouthpiecing involved, it might be useful to and with my peers, it might bring me more patients, but in and of itself is explanation enough…

That is why, in my minority situation I think it’s important MIA is opened to criticism within MIA, to improve the truth value and defensiveness of it’s claims. Otherwise, MIA could be doing easier the job of Mr. Aftab to propel and reify the psychiatrical status quo. It might in the eyes of some skeptics look like claims of cranks.

With all respect and appreciation to MIA, contributors, editors, moderators, readers and above all victims who tried to become commenters.

Report comment

Aftab banks on the fact that most people are taught to believe at face value whatever medical doctors say or too busy too think critically. But little does he know that times have changed….

Report comment

I’m less convinced that Aftab believes the non-sense he spouts, and more convinced there are some deeper psychological issues at work here. Aftab is an “organizational man”, an institutionalized careerist who has to not only believe what he spouts, but has to defend the institution to the extreme, as well as to its fundamental ends (contradiction, ambiguity, and loss of status, all enemies of the careerist). But I totally agree with you that his rebuttals and various comments do elevate Robert Whitaker! But the way I can’t seem to avoid interpreting Aftab, is that he has, by dint of his unwitting hole-laden and selective omission-filled commentaries, positioned himself as a robust advocate for a more intellectually and ethically informed psychiatry. That he (likely) misses this effect, is, for me, at least, rather schadenfreude delicious.

Report comment

I bet on some level Aftab knows he’s a bullshitter, but either way there’s definitely some deeper psychological issues going on in his head, most of which probably have something to do with a not-so-latent fear of losing control of the narrative.

Report comment

I should have just said that I find Aftab to have a proclivity for engaging in various dialogues and critical discourses more like a politician than a doctor or scholar. But that comparison doesn’t exactly clarify his level of integrity, either. But, as Chomsky said, “If what you say doesn’t support the illusions of those in power, what you say can not be heard”. From illusions to hard truths can be an enormous chasm for people with status-power to cross.

Report comment

Robert Whitaker’s scientific reports are always incredibly thorough and meticulous but it’s like the saying when you are directly over the target you will get flak. It’s no surprise psychiatry is always so defensive but I had hoped for better from Dr. Aftab though. His criticisms of Robert Whitaker and MIA are totally out of line.

Report comment

It’s a damning reflection of the bias within the industry that we still have such an inadequate quality of research. Every statement of fact needs to be qualified to recognise that results are inconclusive, and this ambiguity serves the interests of those with more power.

Awais Aftab says:

“In addition to the 67% figure, another misleading statistic is the 3% stay-well rate commonly cited in critical spaces such as Mad in America. Robert Whitaker, for example, frequently points out that only 3% of the patients in STAR*D remitted and were still well at the end of the one year of follow-up.”

To be fair to Awais Aftab, there are examples where you have pointed to this statistic without making the caveat that the results are undermined by the inadequacy of the research. For example:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F5n2SM8SH88&t=2535s

Report comment

Please note: In the youtube interview you have linked to, we are talking about the hiding of long-term results in NIMH trials and the STAR*D fraud. And what I am making reference to is how the 67% remission rate was peddled to the public, while the one-year outcome, as published by the STAR*D investigators in an obscure graphic, which told of 108 as having remitted and not having relapsed by that endpoint, was hidden from the public. That was their bottom-line figure, by the way. And so my point in this interview was that the STAR*D investigators should have made this end-point number known to the public, and if so, they could have explained about the number of dropouts.

Report comment

So many figures and discordant numbers make me feel like I am drowning in my fine grained problems.

Report comment

The expression of “only 3% of the 4,041 patients who entered the trial had remitted and then stayed well and in the trial to its end.” is correct, but still somewhat unclear The STAR*D study has numerous issues, but repeating the 3% figure without explaining its significance might undermine the goals of Mad In America.

If we concentrate solely on the ‘3% stayed well and in the trial’ aspect, it’s understandable to misinterpret it, as it doesn’t actually prove that only 3% remained well; rather, it underscores our willingness to highlight something that is beneficial for our goals. I believe this should be explicitly clarified instead of relying on readers to connect the dots. One approach to achieve this would be to calculate and illustrate the percentage of patients lost to follow-up and explain its relevance to study results.

It’s highly likely that the actual rate of individuals remaining well is significantly higher than 3%, and we should emphasize this. Simultaneously, that same number serves as further evidence that we can’t at all trust the reported 67% remission rate. It just is not as easy for readers to understand that the proven rate of individuals staying well matters and why.

If there are high dropout rates in the study, then it is a likely sign of survival bias. If we consider why someone would not come to visit researchers as promised, and the test subjects consist of depressed people, then the moment their state worsens is the moment they cannot keep their promises.

It’s relatively easy to temporarily improve mood and feelings by using methods and medications that stimulate the nervous system. However, feeling bad and being unable to function is an indicator that our brains need rest and motivation to prioritize self-care, even when external pressures push for the opposite. The challenge lies in the societal pressures imposed by others.

Changing the motivation driven by the body with drugs can lead to adverse consequences in the long run. Natural mood improvement during depression typically occurs when someone is in a precarious situation, providing a temporary ability to surpass natural limits.

Hence, beyond that 67% improvement, there’s a darker narrative of increasing disability that stays hidden for psychiatry emphasizing that figure. Society’s pursuit of happiness and self-motivation, often portrayed through stories of hard work and success, has fostered the perception that the body’s self-regulation is a problem when it causes discomfort, hinders productivity, and leads to thoughts of isolation or despair.

This narrative is easily promoted by doctors who prescribe mood-altering drugs, as who wouldn’t want to be happy? Furthermore, it’s straightforward to design research that seemingly demonstrates significant ‘benefits’ for depression or other mental illnesses. When setting objectives, researchers tend to focus on universally desirable outcomes, labeling them as ‘benefits,’ while deeming their opposites as ‘symptoms.’ It’s a clever maneuver. One just needs to overlook the system’s behavior and concentrate on commonly accepted notions of good and bad.

Why shouldn’t the ability to function better and feel better be indicative of remission and improved health? By shortening the timeline for a year or two and not including the comparison group and forgetting the dropouts we essentially create a research design that produces favorable results for drugs.

Rearranging data, altering the depression scale in use, and modifying the groupings of participants who withdrew from the study can become a form of research in itself. The next time someone conducts similar research, they know how to achieve positive results in advance, adhering to the protocol while still obtaining favorable outcomes for the drugs.

Report comment

‘Fidei Defensor’ – ‘Defender of The Faith’. (Defending the indefensible).

Thank you Robert Whitaker for your meticulous scientific analysis, and for keeping alive global hopes of a long overdue change in the paradigm.

Report comment

Not surprised at all. Obfuscation…is a core of psychiatry. The last book szasz published…Psychiatry: the science of lies.

Maybe seeing this sort of behavior from a psychiatrist who claims to be open to critical analysis of the profession is upsetting. Ok. It is upsetting. Perhaps this should serve to disillusion people who think that there are good well meaning people practicing psychiatry? Clearly this profession is irredeemably immoral..,

Report comment

Indeed. It’s laughable how Aftab positions himself as open-minded yet squawks at Whitaker’s decisive criticism.

Report comment

Great Job as always Robert Whitaker! I’m confident history will show your work and that of MIA was a part and parcel lynch pin of whatever (significant) progress is made in the quality and honorability of the mental health care that (eventually) evolves.

Report comment

I appreciate these comments. I think there is a point of confusion here regarding the nature of this STAR*D study, and what it was set up to “test.” This confusion is present in Aftab’s comments about the 3% figure, and my reply in this post doesn’t really clear up this point of confusion.

This was not a placebo-controlled trial, which, at least in theory, is designed to assess a difference in outcomes between drug treatment and what might called the “natural capacity to recovery”, e.g. the placebo group. The STAR*D study was designed to assess outcomes for “real-world” patients in treatment. The study was not an assessment of the efficacy of antidepressants, but rather an assessment of clinical management of depressed patients by psychiatrists, with antidepressants as the treatment of choice.

As such, keeping people in treatment was a principal outcome to be assessed, and part of the protocol included elements designed to achieve that end. Patients were provided with educational materials that told of the expected benefits of antidepressants (as a treatment for a chemical imbalance, if I remember correctly); they were paid for participating in study evaluations; clinic staff called patients to remind them to come into the clinic; and there was even a newsletter sent to patients encouraging them to remain in the study.

The reason that patients in the acute stage of care were given up to four chances to remit is that was seen to mimic real-world clinical practices. If a first drug didn’t work, then a second might. Or a combination of drugs. And this is why those who dropped out in the acute stage without an exit score that told of remission were counted as treatment failures; the dropouts were rejecting the treatment that was being offered.

The one-year followup was designed with the same thought in mind. The STAR*D investigators wanted to see if the best possible clinical care, with regular follow-up appointments and adjustments of antidepressants, could keep people who had remitted well and in treatment. Once again, dropouts during this phase could be seen as treatment failures; those patients didn’t find it useful to stay in treatment.

Thus, this wasn’t a study of the “efficacy” of antidepressants. This was a study of clinical care of depressed patients treated with antidepressants. It was psychiatry’s clinical care that was being assessed, and those who dropped out, whether in the acute stage or the follow-up stage, were rejecting that clinical care.

As such, dropouts were seen as treatment failures in the STAR*D study. That’s why the graphic in the summary article presented a bottom-line endpoint: Of the 4041 who entered the study only 108 remained in clinical care and still well at the end of one year.

What the STAR*D investigators were hoping for when they started the trial was that there would be a high percentage who remitted during the acute phase, and that they could then keep the remitted patients in treatment for the next year, and that continued antidepressant treatment would be shown to keep a high percentage of remitted patients well. They hoped to show the effectiveness of patients staying on antidepressants and in care, and instead they came up with the dismal result of 3% who stayed well and in the trial.

Undoubtedly, this is also why the STAR*D investigators didn’t want to promote this outcome. Indeed, if dropouts had been followed up and many had been found to have remitted after leaving clinical care, these remissions would raise this question: Why did many patients have to leave treatment in order to get better? Any knowledge about the fate of the dropouts wouldn’t accrue to the perceived benefit of clinical care; it would only add to the picture of treatment failure in this study.

Report comment

Carefully crafted lies masquerading as evidence of psychiatry’s ability to treat so called mental illness…

Despicable but not surprising.

Report comment

I’m seeing something ELSE unspoken here….and un-investigated. WHY did all those people DROP OUT of treatment? No doubt MANY of them dropped out because they were victimizaed by ABUSE from other staff. Verbal, emotional, & psychological abuse, manipulation, gaslighting, and outright LIES, are what TOO MANY psych patients are rountinely subjected to in various community & clinical settings. The so-called “mental health industry” is arguably the most toxic bureaucracy known to man…. But the psychs will NEVER openly discuss these FACTS…. On a near-daily basis, I speak to the VICTIMS of psychiatry & the mental health system. Aftab will NEVER discuss this. Will you, Aftab?….

Report comment

My interpretation is the study shows nothing. There were too many drop outs for the data to show anything useful.

The big question therefore is why did so many people drop out? Did they find the treatment damaging or not effective or were their other reasons?

I wonder if they knew the nature and purpose of the trial, to see if anti depressants helped people in the long term.

When my medications are not working I generally go back to my doctor and if that does not help look elsewhere for guidance. I only stop engaging if they annoy me by persistently ignoring my problems.

Report comment

“I wonder if they knew the nature and purpose of the trial, to see if anti depressants helped people in the long term.”

Actually as Robert Whitaker explained above, that was NOT the nature and purpose of the trial.

The purpose of the trial was to determine whether psychiatric care that included antidepressants was effective in reducing depression.

In Whitaker’s own words:

“Thus, this wasn’t a study of the “efficacy” of antidepressants. This was a study of clinical care of depressed patients treated with antidepressants. It was psychiatry’s clinical care that was being assessed, and those who dropped out, whether in the acute stage or the follow-up stage, were rejecting that clinical care.”

In my view, this is what makes the outcome of the study so damning. Again, the huge dropout rate is a reflection of the REJECTION BY STUDY PARTICIPANTS IN THE USEFULNESS OF PSYCHIATRIC CARE.

That’s not a surprise to many of us here.

Report comment

Aftab wrote: ““How does this (reanalysis) change what we now know about antidepressants? My impression is . . . not much. We have more treatment options now than existed when STAR*D was planned and executed. We have a more somber assessment of the efficacy of traditional antidepressants in general, and partly as a result of STAR*D itself, attention has shifted onto ‘treatment-resistant’ depression.”

This is exactly how STAR*D has misled clinicians, with huge effect on clinical care. It persuades them that the strategy of switching antidepressants results in a high remission rate. We should note that STAR*D did not contain protocols for how these drug switches would be performed nor does it contain any protocols to identify withdrawal symptoms from those drug switches.

From the literature showing widespread misdiagnosis of withdrawal effects, we know that these and other adverse drug reactions are almost universally called “relapse”.

However, the dropouts tell a different story — “of 1,518 remitted patients who entered the follow-up, only 108 patients remained well and in the trial at the end of 12 months. The other 1,410 patients either relapsed (439) or dropped out (971).” 971 of 1518 = 64% dropouts of *remitted* patients. You would think if the 64% were pleased with their ongoing drug treatment, they’d stay in the study.

Aftab claims the attention STAR*D brought to “treatment-resistant depression” is a benefit of this huge, expensive study. However, “treatment-resistant depression” by definition requires multiple failed antidepressant trials, any of which may cause adverse effects misdiagnosed as “treatment resistance”. It’s entirely possible that what STAR*D modeled was not optimum clinical practice by endorsing drug switches to find the “right antidepressant”, but an iatrogenic process to generate “pseudo-resistance”, widely misdiagnosed as “treatment-resistant depression”.

Report comment

In a quasi-religion, doctrine doesn’t need to make sense.

Report comment

I tried to follow this story. Today I noticed an interview with Awais on the “Digital Gnosis” YouTube channel which I have yet to watch. I did comment underneath about his response to the MIA article and urged the host to investigate.

It could be a way of highlighting the case..

Report comment