On May 7, JAMA Psychiatry published a review of the efficacy of antipsychotics over the short-term, and if the article is carefully parsed, the results reveal that there is no good evidence that antipsychotics provide a clinically meaningful benefit, compared to placebo, over the short-term. This might seem startling to the public and to prescribers, as it is understood to be a given that antipsychotics are effective in curbing acute episodes of psychosis, but in fact it is a finding that can be easily explained, and one that is consistent with an exhaustive 2017 meta-analysis of antipsychotic drug trials.

The authors of the JAMA Psychiatry article conclude that their findings show that antipsychotics are effective over the short-term, which is the same conclusion made by the authors of the 2017 meta-analysis. They do so because both analyses tell of a “statistically significant” drug-placebo difference in the reduction of symptoms on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS.) What the investigators in each study fail to note is that the drug-placebo difference is quite small (less than 10 points on a 210-point scale), and doesn’t rise to the level of a “minimum clinically important difference.” Indeed, a 9-point drug-placebo difference on the PANSS scale is so small that it most likely wouldn’t be clinically noticeable by either the patient or provider.

In short, here is a summary of the evidence base, compiled over a period of 70 years, for the short-term use of antipsychotics as a treatment for acute episodes of psychosis:

- No good-quality studies have ever been conducted in medication-naïve psychotic patients. Thus, there is no evidence that they are effective for treating patients suffering a first episode of psychosis.

- There are no good-quality studies in patients suffering an “early episode” of schizophrenia that provide evidence that antipsychotics are effective over the short term.

- While there have been hundreds of RCTs in chronic psychotic patients that have found that antipsychotics provide a statistically significant benefit over placebo in terms of reducing symptoms, the drug-placebo difference in these studies does not rise to the level of a “minimum clinically important difference.”

As such, a startling conclusion arises from the two meta-analyses of RCTs of antipsychotic trials: even though antipsychotics have been prescribed to curb acute episodes of psychosis for 70 years, there is no evidence that they provide a meaningful benefit to any group of psychotic patients.

No Trials in Medication-Naïve Patients

When the first antipsychotic, chlorpromazine, was introduced into asylum medicine in 1954, there was no FDA requirement that the manufacturer of a drug had to conduct randomized clinical trials to prove its efficacy. At that time, all a drug manufacturer had to do was run a small trial to assess safety to gain FDA approval. The adoption of antipsychotics in the 1950s was driven by pronouncements from psychiatrists that chlorpromazine was a wonder drug that could reliably knock down psychotic symptoms.

In 1962, the FDA began requiring drug manufacturers to conduct RCTs that assessed the efficacy of a new drug, and since that time hundreds of RCTs of antipsychotics have been conducted. However, researchers who have reviewed this 60-year database of RCTs have not found a single trial that assessed the merits of an antipsychotic in first-episode, medication-naïve patients. Here are two examples of such admissions:

- In a 2017 review, Donald Ross and colleagues concluded that “no placebo-controlled trials have been reported in first-episode patients.”

- That same year, Stefan Leucht and colleagues, in their review of “Sixty Years of Placebo-Controlled Trials in Acute Schizophrenia,” wrote that “there were no studies exclusively examining first-episode patients.”

However, there is one bit of evidence that can be dug up from the research literature that provides a hint of the efficacy of antipsychotics in first-episode patients. In a study of 1,413 first-episode male schizophrenic patients admitted to California hospitals in 1956 and 1957, the California department of mental hygiene found that “drug-treated patients tend to have longer periods of hospitalization . . . furthermore, the hospitals wherein a higher percentage of first-admission schizophrenia patients are treated with these drugs tend to have higher retention rates for the group as a whole.”

That study, while not an RCT, nevertheless tells of how chlorpromazine may have slowed the recovery of first-episode patients, as opposed to helping psychotic patients recover faster.

No Quality Trials in “Early Episode” Schizophrenia Patients

Although researchers today can’t identify a single RCT study of antipsychotics in medication-naïve patients, there were a handful of NIMH studies conducted in the 1970s that sought to assess the merits of antipsychotics in “early episode” schizophrenia patients. In a 2011 Cochrane review, John Bola and colleagues combed through the research literature to find studies of antipsychotics in patients suffering a first or second episode of psychosis, but they could only find five that compared antipsychotic treatment to placebo, psychosocial care or milieu therapy.

The data reporting from these studies was “very poor,” they wrote. The only finding they could extract from the five studies was that those in the placebo group were more likely to leave the study early, while the patients treated with antipsychotics were at increased risk of suffering from the adverse effects of treatment. “Data are too limited to assess the effect of initial antipsychotic medication treatment on outcomes for individuals with an early episode of schizophrenia,” they concluded.

Thus, there is no good-quality RCT evidence that antipsychotics are effective over the short term for treating an “early episode” of schizophrenia.

Short-Term Results in Chronically Ill Patients

In their 2017 review of antipsychotic drug trials, Leucht and colleagues identified 167 RCTs published from 1955 to 2016 that met their inclusion criteria for review. The short-term studies, typically lasting six weeks, involved 28,102 patients, with a mean age of 38.7 years and a mean duration of illness of 13.4 years.

As Leucht and colleagues were unable to find any good-quality studies in first-episode or early-episode schizophrenia, they noted that the outcomes were “representative only for chronically ill, often previously treated patients.”

They found an “effect size” for reduction of symptoms of 0.47, which, they wrote, translates to a drug-placebo difference of 9.6 points on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS). As will be seen below, this drug-placebo difference falls below a “minimum clinically important difference.”

Even without that minimal clinically important difference reference point, the finding of an effect size of 0.47 does not tell of a treatment that provides a benefit to the majority of patients. Here is a graphic that shows the symptom overlap between two groups with an effect size of 0.47:

There is an 81% overlap in the reduction of symptoms with an effect size of 0.47. As Leucht noted, this produces a “number needed to treat” (NNT) of six, which means that six patients need to be treated to produce one patient who benefits from the treatment. The other five are exposed to the adverse effects of antipsychotics without any additional benefit beyond placebo in symptom reduction, and thus could be said to be harmed by the treatment.

However, for the purposes of this report, on whether the clinical trials of antipsychotics provide evidence of a clinically meaningful benefit, the key statistic is the drug-placebo difference of 9.6 points on the PANSS. While that difference may be statistically significant, it does not rise to the level of a minimum clinically important difference.

No “Minimum Clinically Important Difference”

As a 2012 article in The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry explained, the “concept of the minimum clinically important difference” emerged as a way of assessing the clinical relevance in “standardized instrument scores” used in RCTs. The minimum clinically important difference is defined as “the smallest difference in a score in the domain of interest which patients [or providers] perceive as beneficial and which would mandate, in the absence of troublesome side effects, and excessive cost, a meaningful change in the patient’s management.”

The importance of the minimum clinically important difference, they added, is to determine “if small statistically significant differences in measurement scores in studies with large sample sizes are great enough to be considered clinically meaningful.”

This 2012 paper was authored by researchers at Yale and Columbia University, one of whom was Robert Rosenheck, who is well known for his schizophrenia research. PANSS rates the severity of 30 symptoms on scores of 1 to 7, such that the possible range of scores is 30 to 210. Rosenheck and colleagues determined that the drug-placebo difference on the PANSS must be at least 15 points to be clinically meaningful.

As can be seen, in Leucht’s meta-analysis of 60 years of antipsychotic studies, the drug-placebo difference of 9.6 points on the PANSS fell short of the minimum clinically important difference. Moreover, this was the difference in trials where the placebo group is mostly composed of chronic patients who have been withdrawn from their medication, with such drug withdrawal known to put psychotic patients at increased risk of relapse for the next few months.

JAMA Psychiatry’s 2025 Study

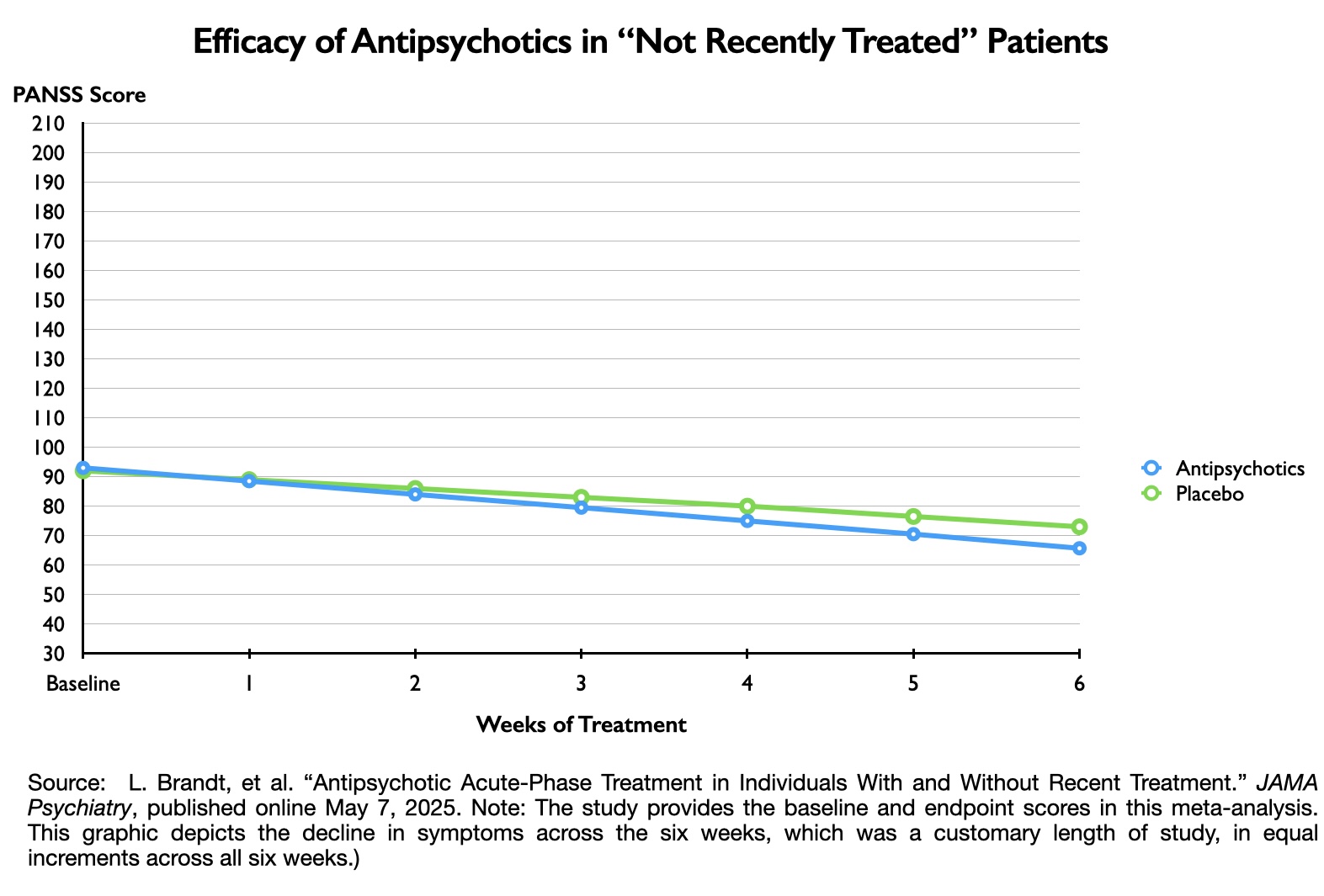

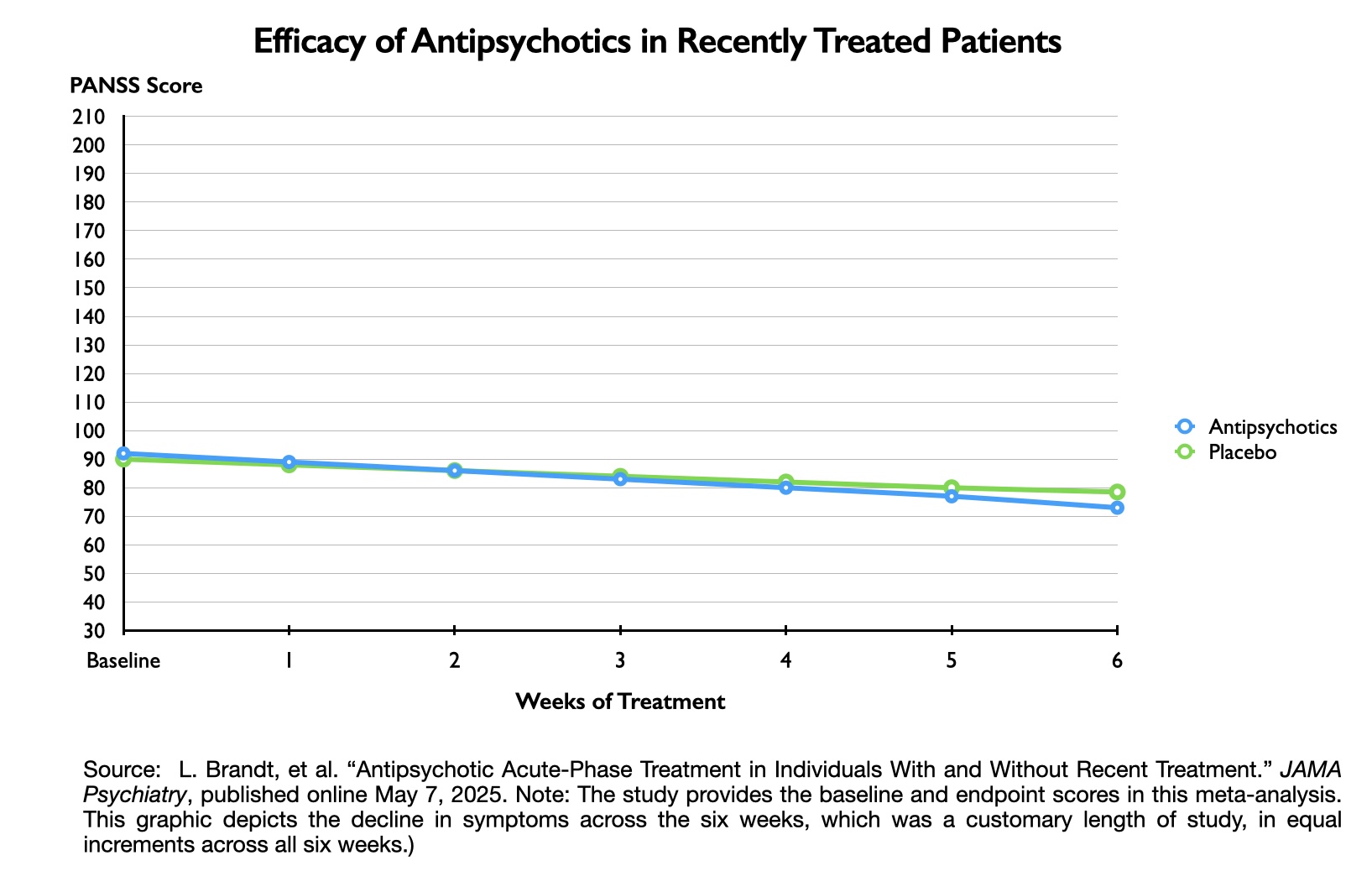

The study published in the May issue of JAMA Psychiatry provides further details about the drug-placebo difference on PANSS in short-term trials of antipsychotics. The findings, when depicted in a graphic, provide a visual understanding of why an 8- or 9-point drug-placebo difference isn’t clinically meaningful. (Leucht was one of the authors of this meta-analysis as well.)

The study was designed to assess if short-term outcomes differed according to whether the patients had not taken an antipsychotic in the previous month, compared to those who had been “recently treated” with an antipsychotic. The researchers found 12 studies that enabled this comparison, with 692 patients in the “not recently treated” group, and 2,089 in the “recently treated group.”

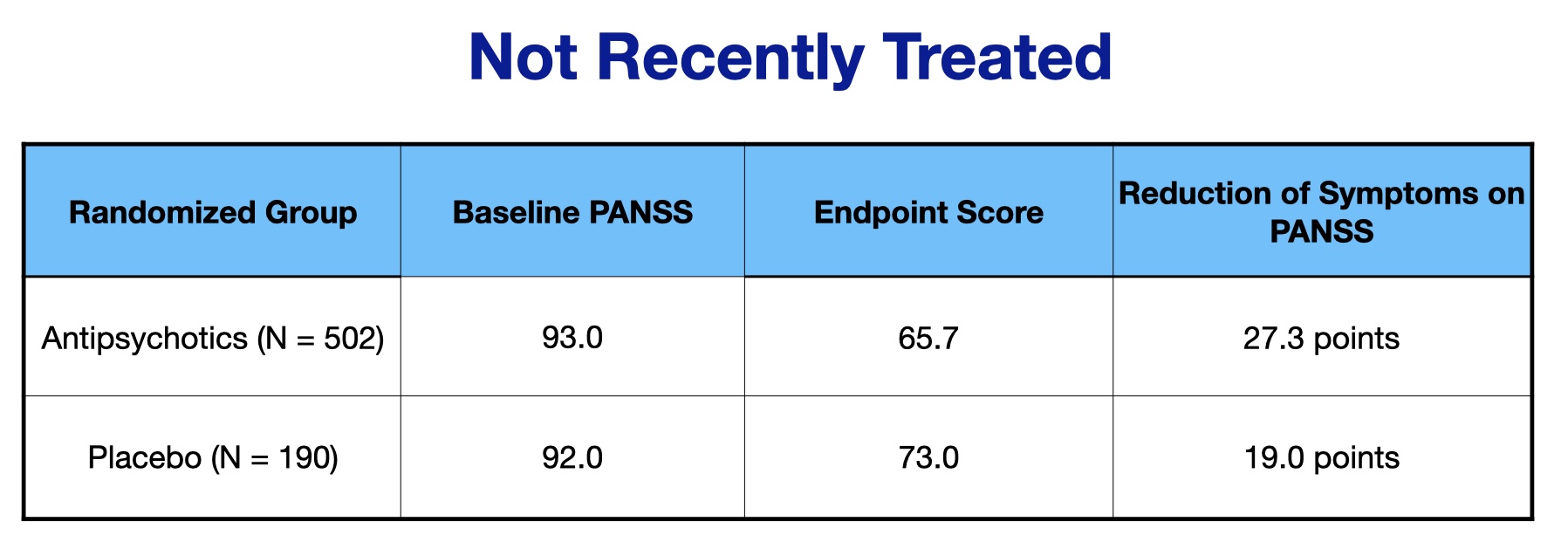

Here are the PANSS scores for the not recently treated group:

As can be seen, the drug-placebo difference on symptom reduction on the PANSS scale was 8.3 points in the “not recently treated” group (27.3 – 19.0).

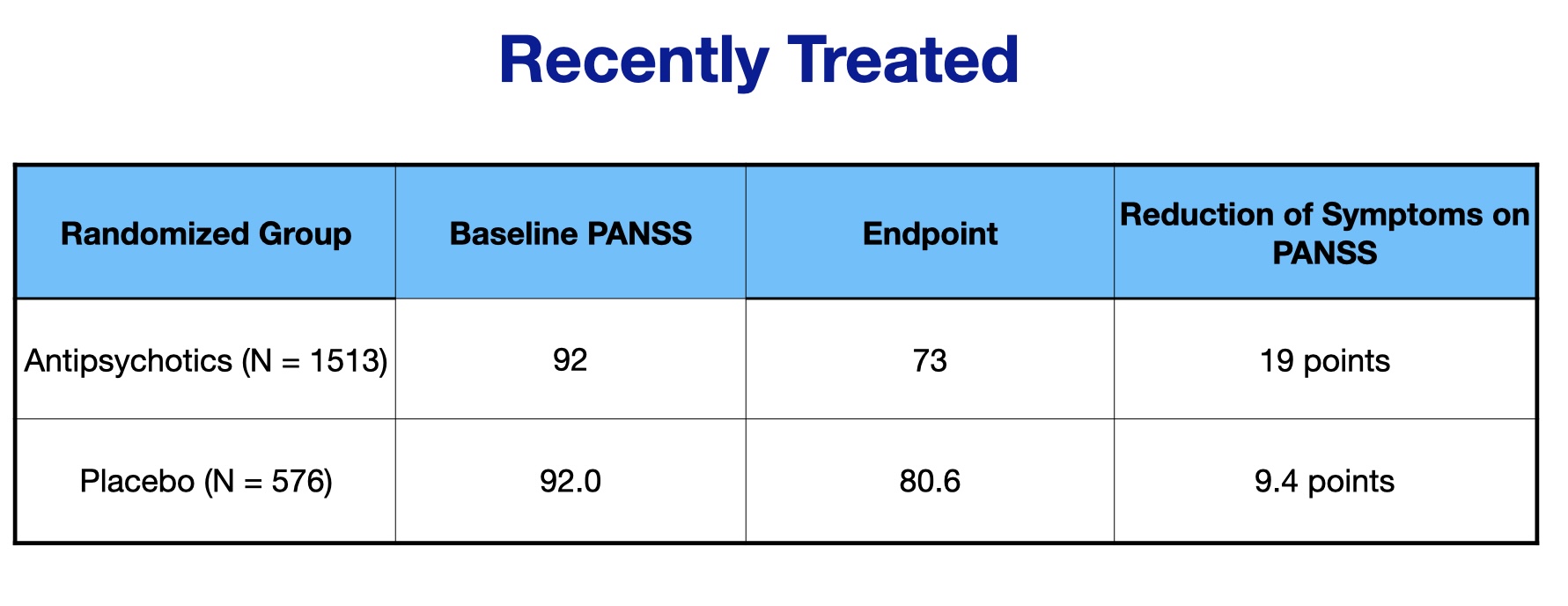

Here are the PANSS scores for the recently treated group:

The drug-placebo difference for this group was 9.6 points (19 – 9.4). Thus, in neither grouping of patients was the drug-placebo difference near the 15 points required for a minimum clinically important difference.

The graphics below depict these drug-placebo differences, which provide a visual sense of how the outcomes for those treated with antipsychotics failed to separate from the outcomes for the placebo groups. If a treatment is clinically meaningful, then there should be a clear separation from outcomes for the placebo cohort.

Thus, in this 2025 meta-analysis, the data tell of a treatment that failed to provide a minimum clinically important difference, and graphing the results on a 210-point scale visually reveals how the drug treatment failed to notably separate from placebo. Yet, in both cases, the drug-placebo point differences were “statistically significant,” which led Leucht and colleagues to conclude that antipsychotics were effective in both groups of patients.

“This study’s findings confirm antipsychotics as a treatment option for both ‘not recently treated’ and ‘recently treated’ individuals,” they wrote. “This supports current treatment guidelines in schizophrenia, which recommend antipsychotics as a first-line pharmacological treatment option.”

Summing up the Evidence for Short-Term Use of Antipsychotics

With this brief review, it is now easy to sum up the evidence base for use of antipsychotics to curb acute episodes of psychosis:

- There is no evidence supporting their use in medication-naïve patients.

- There is no evidence supporting their use in early-episode schizophrenia.

- Sixty years of clinical studies show that antipsychotics do not provide a “minimum clinically important difference” in chronic patients.

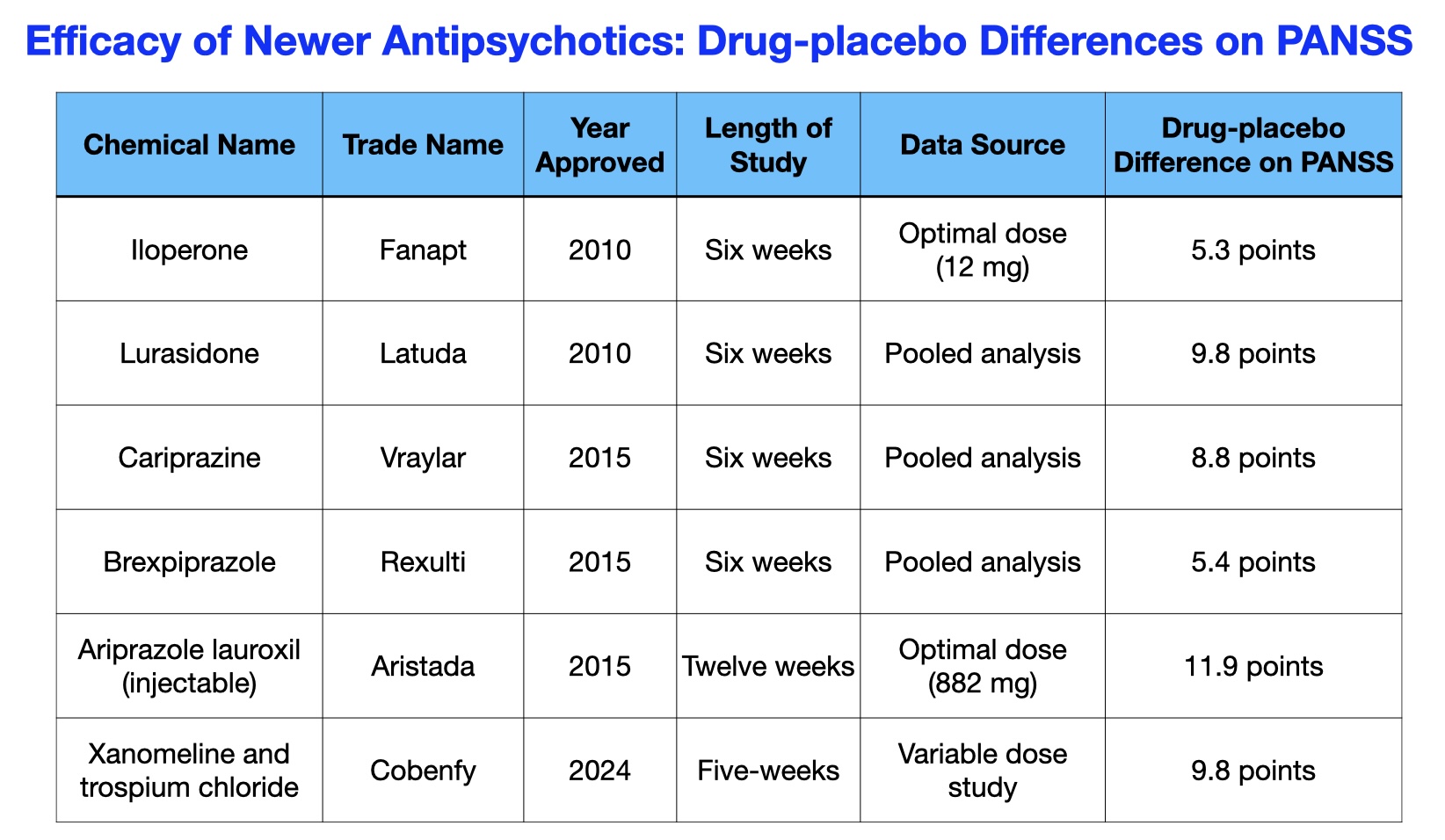

Efficacy in Schizophrenia Drugs Approved Since 2010

As new antipsychotics come to market, they are often touted as providing an additional benefit compared to antipsychotics already on the market. However, Leucht’s 2017 meta- analysis included studies of the atypical antipsychotics that came to market from the early 1990s to 2010, which did not show that these “second-generation” antipsychotics produced a “minimum clinically important difference.” A review of schizophrenia drugs approved since 2010 reveals that remains the case for the newer drugs as well.

In the table below, the drug-placebo difference in PANSS score for each drug is either from a pooled analysis of pivotal trials, or from a single trial at the most effective dose.

The drug companies that brought these six new schizophrenia drugs to market conducted multiple phase II and phase III trials, and regularly tested multiple doses to find an “optimal dose” that showed greatest efficacy over placebo. Yet, there wasn’t a single study for any of these drugs that showed the antipsychotic provided a clinically meaningful benefit.

The drug companies that brought these six new schizophrenia drugs to market conducted multiple phase II and phase III trials, and regularly tested multiple doses to find an “optimal dose” that showed greatest efficacy over placebo. Yet, there wasn’t a single study for any of these drugs that showed the antipsychotic provided a clinically meaningful benefit.

RCTs as a Source of Clinical Illusion

Randomized double-blind clinical trials are considered the gold standard for assessing the short-term efficacy of a medical intervention. In the case of antipsychotics, the RCTs are presented to the public and to prescribers as evidence of the efficacy of antipsychotics for treating acute episodes of psychosis, and as a treatment for schizophrenia. That bottom-line conclusion leads to a one-size-fits all clinical practice, with the routine prescribing of antipsychotics for all those with “psychotic” symptoms.

In essence, the RCTs have fostered an illusion of efficacy. It is also easy to see, from a careful parsing of the RCT data, why clinicians perceive antipsychotics as somewhat helpful, which helps reify the belief that their short-term use is evidence-based.

If you look at the change in PANSS scores for those treated with antipsychotics, in the absence of a placebo comparator the diminishment in symptoms over six weeks does rise to the level of clinical importance. For instance, in the meta-analysis published in JAMA Psychiatry in 2025, the PANSS scores for the medicated patients decreased more than the “minimum clinically important” threshold of 16 points, which is a clinically noticeable difference. However, prescribing physicians do not see the drug-placebo difference, because in regular practice they are treating everyone with antipsychotics, and so they are blind to the improvement that occurs in non-medicated patients.

Once this clinical experience is understood, it is easy to see how RCTs can foster harmful clinical practices. The RCTs of antipsychotics have been conducted in a subset of patients (chronic patients), and yet are presented as applicable to all psychotic patients. And while RCTs of antipsychotics may tell of a statistically significant reduction of symptoms, which is cited as evidence of their benefit, the failure of that drug-placebo difference to provide a clinically meaningful benefit is almost never mentioned, either in pronouncements to the public or in the medical literature. As a result, rather than serve as a source of illumination, RCTs in this case have served as a source of darkness, used by psychiatry to present to the public and to prescribers an unfounded story of efficacy.

The failure of the existing research to guide use of the drugs is so all encompassing that, in order for psychiatry to claim that short-term use of antipsychotics is “evidence-based,” it needs to start over its testing of this class of drugs. It needs to conduct RCTs in medication-naïve patients and early-episode patients, as well as in chronic patients, and rather than rely on “statistical significance” as a marker for efficacy, rely on the “minimum clinically important difference” as the standard.

What use of antipsychotics to curb acute episodes of psychosis would emerge from robust RCTs of that kind?

One likely answer is that, particularly in first-episode psychosis, or early-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorders, initial use of antipsychotic drugs would be delayed, a practice developed in Northern Finland in the early 1990s as part of its Open Dialogue therapy. This delay in initiation of antipsychotic medication enabled two-thirds of their patients to recover without being exposed to the drugs, and enabled five-year outcomes for Open Dialogue patients that were far superior to outcomes in the U.S. and the rest of the “developed” world. As for their use in chronic patients, the existing literature suggests that their use should not be a first-line therapy, but rather reserved for those who fail to improve with non-drug therapies.

However, in the absence of RCTs that can answer such questions, the public and prescribers need to become aware of the startling conclusion that emerges from meta-analyses of short-term RCTs of antipsychotics, which is that 70 years of RCTs have failed to provide evidence that they provide a clinically meaningful benefit to first-episode patients, early-episode patients, and chronic patients. Once the shock of that conclusion sunk in, then the door to a best-use model could begin to open.

If we take this at face value then considering the shear number of severe side affects as in the case of law:”ignorance is no excuse for the law”. This law should certainly apply to prescribers with even more severity. Jail time perhaps, revoke a license or two. Alternatives welcome.

Report comment

I wonder what would happen with an active placebo, probably all difference between groups would disappear.

Report comment

A damning analysis, thanks.

Report comment

It may but I think this case is closed.

Report comment

A nice re-evaluation of the 70-75 years.. In summary… None of the psychiatric drugs are beneficial; on the contrary, they are harmful..

If we think about it.

A) Despite the fact that there is no lots of evidence that the psychiatric drugs prescribed to patients for 70/75 years are “useful” and treat mental illness…

B) Despite the lots of evidence that psychiatric drugs cause mental illnesses…

C) Despite the lots of evidence that psychiatric medications cause both mental and physical harm (iatrogenic mental and physical injuries)…

D) Despite the lots of evidence that psychiatric medications make people more likely to commit violence, murder and suicide…

E) Despite the lots of evidence that psychiatric drugs cause deaths…

Etc etc…

Despite all these harms, it is not possible to logically explain why psychiatric drugs are still prescribed by psychiatrists, are on the market, and clearly harm people (causing deaths and iatrogenic injuries). In fact, the fact that psychiatric drugs are still used despite their “fatal harms, iatrogenic physical and mental injuries”, including death… is a sign of “INSANITY” from the perspective of “states, mainstream medicine (real doctors) and societies”.

Probably… When politicians and real doctors go crazy (i.e., when normalization is disrupted, such as not having a healthy mind, increasing corruption (fraud) in scientific studies, etc.), we can naturally see that societies are also affected by them and exposed to a “sign of madness”.

In other words.. We can say that the fact that a country’s politicians and doctors are not normal is a factor that can lead to the society not being normal.. The fact that psychiatric drugs that clearly harm and kill people are still used shows us that states, doctors and societies do not have a ‘normal society’. This is called “death in plain sight”.

***

The ongoing secret genocide of psychiatry…

Probably.. Psychiatry (due to psychiatric drugs) has caused the deaths and iatrogenic mental and physical injuries of at least 1 million people per year during the last half of the 20th century (1950-1999). This could mean the murder and mutilation of an estimated 50 million (perhaps tens/hundreds of millions) of people in the last 50 years of the 20th century.. Considering that the same deaths and injuries are still occurring, this number could be even higher.

Probably… Psychiatry has caused the deaths and iatrogenic mental and physical injuries of tens/hundreds of millions (perhaps more than 1 billion) of people in total during the last half of the 20th century (1950-1999) and the first quarter of the 21st century (2000-2025).

If we consider that more than 1 billion people today are officially diagnosed with “mental illness”… this could mean that at least 1 million more people die and become disabled every year. This possibility makes psychiatry the world’s most dangerous genocidal agent.

Probably… Psychiatry is committing the world’s greatest genocide, killing and maiming at least 1 million people (maybe more) every year worldwide. Psychiatry seems to be continuing the SILENT GENOCIDE it committed in the 20th century in the 21st century.

***

The question that needs to be asked here is: “Who will STOP this?” HONEST doctors outside of mainstream medicine need to expose this hidden genocide. Honest doctors need to expose the people who die (especially the people who are injured and disabled) from psychiatric drugs… as the real cause of their deaths and injuries. Because mainstream medicine seems reluctant to expose this.

The medical world, which investigates every detail of a murder or poisoning and reveals the causes of it, is unable to reveal the harms of psychiatric drugs and the causes of death. This is a very strange situation. They could reveal it if they wanted to. But they don’t. Because there is MONEY involved. We are talking about a source of income that is being transferred from psychiatric drug manufacturers to the mainstream medical world. These have been revealed before. MONEY talks in the medical world. Mainstream medicine doesn’t care if people die or are injured. But they give you ‘fake smiles’ as if they care.

Therefore, there is a need for honest doctors and other honest scientists, etc… There is a need for honest people such as honest doctors who do not serve mainstream medicine… honest psychiatrists, psychologists who do not serve mainstream psychiatry… honest journalists, writers, intellectuals who do not serve mainstream media… honest researchers who do not serve mainstream science… honest politicians who do not serve mainstream politics, etc…

I hope… We hope that the number of honest psychiatrists, doctors, psychologists, journalists, intellectuals, writers, researchers, politicians, etc. will increase and all the facts about the deadly harms of psychiatric drugs will be revealed.

Thank you for reviewing the last 70 years Robert Whitaker.. Best regards..

With my best wishes, Y.E 🙂 (Researcher blog writer (Blogger))

Report comment

I remember a study where they brought people who were showing signs of psychosis and this took place back around the 1820s. They brought these individuals who had very serious mental disturbances out to a very nice place in the country. Then they began to treat them kindly and made sure they were given proper nourishment and were given things to do. It was surprising because in about 3 months all of them went back into society and began to work again. They were cured of all of their symptoms.

Report comment

Hi, Ted LaCroix.. Thank you for your answer. If you allow me, I will explain my thoughts.

This ‘treatment method’ you mentioned is actually ‘behavioral therapies’ applied to treat people with “mental illnesses” that have continued throughout human history. These were applied successfully in the times of the Prophets and in later periods. Being kind, eating right, and doing things to do (i.e. various jobs, hobbies, etc.)…

We can add ‘cleanliness’ to these… Physical and spiritual cleansing.. Physical cleansing is body and environmental cleansing. These are important factors in not getting mental illnesses. Body cleansing should not be seen as just washing the body with soap and water. We also need to be careful about the food and beverages we eat and drink, and even the medications we use (especially psychiatric). (For example, psychiatric medications do not cure mental illnesses; on the contrary, they create them.) Spiritual cleansing is achieved through spiritual rituals such as ‘being kind, doing a job, being good’.

Believing in God is also included in this. However, this is not the criterion; anyone who wants to believes, anyone who doesn’t, but believing (believing in God) can prevent you from falling into the trap of mainstream psychiatry. (However, this may not be true for most believers. Because, being deceived, cheated and helpless are the biggest factors in this.)

Even Thomas Szasz, who fought against mainstream psychiatry, could not escape the influence of mainstream psychiatry. Because disbelief pushed him into this trap. Because mainstream psychiatry is based on ‘disbelief’. For this reason, it can easily kill and maim millions of people every year. If it had been based on faith, these deaths and injuries might never have happened.

Thomas Szasz fell victim to disbelief and before he died he hinted that ‘normal psychiatry’ (not mainstream psychiatry, but just that) should survive. So, Thomas probably… might have hinted that psychiatry (and psychiatrists) should ‘normalize’ as soon as possible and that this normal psychiatry should survive.

So.. We can think like this; Psychiatry (and psychiatrists) need to get rid of the mainstream structures and ‘normalize’ as soon as possible. In order for psychiatry (and psychiatrists) to become normal, psychiatry (and psychiatrists)… must first stop denying the deadly harm of psychiatric drugs, acknowledge it, and shout to the world that they should be banned. (If psychiatrists want to be real doctors (and act like real doctors), they must do these things.) This is the only way for psychiatry (and psychiatrists) to normalize. Without these, it seems unlikely that psychiatry (and psychiatrists) will normalize.

Without these, it seems unlikely that psychiatrists will remain real doctors and physicians. They have the legal title of ‘doctor’, but there are numerous studies and researches that reveal that they are ‘quacks’ and not ‘real doctors’. And billions of societies that learn these…

Unfortunately.. Probably… Psychiatrists serving mainstream psychiatry are responsible for the murder and mutilation (iatrogenic injury) of tens/hundreds of millions (at least more than 1 million) of people worldwide each year.

Unfortunately.. Probably… Governments pay psychiatrists who serve mainstream psychiatry a regular monthly ‘doctor’s salary’ for damaging healthy people’s brains (and causing them to die and become disabled every year). This situation provides psychiatrists with an indescribable opportunity and possibility to ‘damage the healthy brains of many more people and to kill and injure them’.

Unfortunately, this is the truth. Probably… States (and Governments) and the mainstream medical world seem to know about this ‘hidden genocide’ that psychiatry commits on a regular basis every year. They know but they don’t make a ‘sound’. Why? Because it seems like there is MONEY involved.

Actually, it’s not just money. There is also an attempt to reduce the human population. It seems that the governments and the mainstream medical world have chosen to start with those they see as mentally ill in order to reduce the human population of the world. And for the last 75 years. How many tens/hundreds of millions/billions of people have been killed and maimed (injured) by psychiatry during 75 years?

***

Today, it is important to know that the vast majority of the tens/hundreds of millions of people with mental disabilities who have to stay in mental health units such as ‘mental hospitals, psychiatric hospitals, rehabilitation centers, nursing homes, care homes’ until they die around the world… have had their healthy brains chemically damaged (chemical brain damage) by psychiatric drugs.

When I told a female nurse working in a mentally disabled care home that the reason for the mentally disabled people in this care home being in this state (i.e. the reason for their brain damage) was/could be ‘psychiatric drugs’… she said to me ‘you are dreaming, this is your thinking, these are all conspiracy theories, there is no such thing…’

Of course, what answer would you expect from a nurse? Tell your ‘circle’ that psychiatry carries out a genocide every year, they will immediately call you a ‘conspirator (conspiracy theorist)’. You can be sure of that..

Best regards, 🙂 Y.E.

Report comment

What you have said is what I have known for at least 50 years and I think you may want to expand on it and publish a small book and then try to sell it. It is obvious to me what you have said has all taken place and that means it all has to do with MONEY. WE also need to take big oil into consideration because plastics and other chemicals from the chemical engineers put drugs (bad drugs) into capsules when they could use gelatin and put vitamins and minerals into capsules instead and may be able to cure and make all of the illnesses psychiatrists have currently and historically caused, go away if they also feed and house people for a month or two after they have been exposed to the harsh realities of life and have no one to help them. I was reading and I read that we all may have the equivalent of a plastic teaspoon that has collected over a certain amount of decades dependent on how old we are, in our brains. Scientists were wondering amongst themselves how to get rid of the plastic in our bodies and brains and so far have said it is impossible because in the brain you would also need to get rid of too many brain cells to successfully remove the plastic. I have heard of how are brains have a remarkable capacity to heal because the brain has much more plasticity than we knew, but I think having a plastic teaspoon’s worth of plastic in my brain doesn’t improve the function of it. Thank you for what you have written and we are on the same page.

Report comment

Thanks Ted LaCroix… Have nice a weekend.. 🙂

Report comment

Pharma products are often not as safe or effective as purported to be, but this illusion is rampant in psychiatry and extra dangerous for patients who are at their most vulnerable because they are viewed as ‘mentally ill’, or lacking insight, etc, and what they say, think or feel is dismissed. Your work is of great importance and benefit to those who have the misfortune to be put in this difficult situation and end up harmed in a life altering, or life ending, manner. This is why I really think you are doing God’s work.

During cancer treatment chemo and steroids had made sleep difficult and I was told to go see ‘someone’ for “help with sleep meds”. The ‘someone’ turned out to be a young psychiatrist who immediately prescribed Seroquel. I had no idea what this pill was, let alone that it was an anti-psychotic (if I had been informed I would have declined it). The first night I took the Seroquel turned into a scary experience. I woke up a couple hours later hallucinating, shaking and as I tried to walk to the washroom my legs would not hold me up and I had to crawl. Needless to say I did not get any more sleep that night. I told the psychiatrist of the bad experience but she could not have cared less. I declined to take any more Seroquel so she prescribed a laundry list of other drugs (benzos, AD’s) that also had some unpleasant side effects and I had to quit. I managed to continue with one for about 3 months before tapering off. When I later obtained my electronic records I saw she had published a 4 page ‘psych report’ in which she totally mocked me for having any side effects to any of the drugs she had prescribed.

Thank you for continuing your amazing work and detailed reporting Robert.

Report comment

It seems to me that despite all the harm that these drugs do, the doctors seem to want to believe that they work……It’s kind of like saying that you can hammer with a screwdriver. You can, but is it effective?????

Thanks for all of your time in researching and writing this article.

Report comment

Seems to me more like solving a programming problem by replacing memory cards. The solution has nothing to do with the problem!

Report comment

Nicely and neatly put, as EVER, Mister McCrae, thank YOU.

“Brevity is the soul of wit” comes from perhaps the most pertinent passage of Polonius or anywhere in all of “Hamlet,” and perhaps in all of Shakespeare, don’t you think?

But is what we term psychosis most usefully to be viewed as a problem to be solved or dissolved, or, as the word itself hints, as a psychic process to be used as best we can discover?

Carl Jung, for one, seems to have discovered how to reap inestimably rich rewards from his process, as Lincoln and Churchill from their melancholies, don’t you think?

From this perspective, of course, as Bob himself was perhaps the first to very publicly point out, the word “antipsychotic,” like “antidepressant” (and, indeed “clinical” in this context), is most tremendously and perniciously – not to mention sickeningly – misleading.

As Thomas Szasz pointed out, this would hardly matter were coercive psycho pharmacology no longer state-sanctioned.

Thank you for your soulful wit!

Tom.

Report comment

It is fantastic to find research that backs up my experience of antipsychotics. I don’t believe they had any effect on my “psychosis”. The adverse effects, and withdrawal effects, however, were real and devastating.

No doubt the machine to “defend the drug at all costs” will spring to life one again, and we will be inundated with sloppy science and carefully curated opinion pieces with those harmed blocked from the conversation.

Report comment

Psychiatrists are guilty as charged.

Report comment

I’d like to know given the conclusions of the studies why there has not been a massive class action lawsuit with regard to those who have been harmed by the drugs that have been mentioned. I’d also like to know why it continues to happen. I know already why and it is because the pharmaceutical industry wants to make as much money as possible and seemingly doesn’t care who is damaged by giving people drugs that harm a person’s brain instead of helping a person’s brain.

Report comment

Only one minor comment: Shouldn’t the two figures with PANSS have a y-axis from 30 to 210 instead of 0-210, since 30 is the minimum possible score on PANSS?

Report comment

You are right . . . I redid those graphics so the scale now reads 30 to 210. The article stated that the range of possible scored was from 30 to 210, and now the graphics reflect that. Thank you for pointing that out.

Report comment

The same problem can happen with RCTs of psychotherapy. See Smoke and Mirrors: How You Are Being Fooled About Mental Illness, pp. 187-199. https://www.amazon.com/Smoke-Mirrors-Illness-Insiders-Consumers/dp/0578639262

Report comment

“However, researchers who have reviewed this 60-year database of RCTs have not found a single trial that assessed the merits of an antipsychotic in first-episode, medication-naïve patients.”

I did try to test this, since I had a loved one, who was dealing with alcohol encephalitis, which mimics the symptoms of “schizophrenia,” but he was in his late 50’s when this happened, not young. I asked doctors to avoid the anticholinergic drugs (antidepressants, antipsychotics et al), since I knew both me and my grandmother, neither of whom were dealing with alcohol encephalitis nor “psychosis,” were made ungodly sick on them.

And, in much as I’ve yet to be given the right to see my loved one’s medical records, and don’t think he’s even picked them up himself, so can’t claim to know with certainty. But, in as much as I know the anticholinergic drugs are problematic for innocent females, who speak out against the systemic child abuse covering up problems within our society. I don’t know whether or not the neuroleptics are, in a very short run manner, a needed short run fix for alcohol encephalitis, which may likely be a probable common cause of psychosis.

But I have been pointing out for decades that the antipsychotics / neuroleptics, used long term, in combination, or inappropriately, are very dangerous. Because the anticholinergic drugs can create the positive symptoms of “schizophrenia” via anticholinergic toxidrome, and the negative symptoms of “schizophrenia” via neuroleptic induced deficit syndrome. Not to mention, if used long term, they result in a nasty drug withdrawal induced manic “psychosis,” but which also for me, was also an awakening.

I did find that a benzos didn’t work short term for my loved one, but maybe (I don’t know, since I haven’t seen my loved one’s medical records) an antipsychotic did work short term, then a short term course of a low dose of lithium did work. My loved one has been psych drugs free, and doing well for a while.

Thank you, Mr. Whitaker, for all you do, and say. And thank you for letting us independent medical researchers allow to speak.

And I do agree with you, James, ”ignorance is no excuse for the law,” so the psych “professionals,” who now all claim ignorance, when no medically trained doctor can claim ignorance, are not innocent. Wake up lawyers.

Report comment

Cards on the table: I’m a psychiatrist who has prescribed these meds for 40+ years and seen them do wonders. I’ve also seen them do nothing, and I’ve seen them make things worse. I consider myself a slow-to-prescribe doctor and judicious in how I do that ( and I’m sure 99% of psychiatrists say the same thing). I am committed to collaboration with patients and ( if appropriate) families. I have been saddened, embarrassed and horrified by some of the shoddy care that some has received. I have been following MIA to get some balance, and understandable as it may be, seeing people like me as the enemy is a non-starter in this world, just as if I were to see family members as my ( or the patient’s) enemy.

So, a few brief points:

(1) We all are affected by what we see in front of us. If I see a patient improve a few days or weeks after starting antipsychotic X, I’ll agree it might be placebo or some other factor, but you cannot prove to me ( or the patient, often) that the med played no role. I could be fooled, but maybe not. If we stop the med and the patient gets worse, and then we resume it and s/he gets better, tough to insist that the med is useless.

(2) RCTs are important, but as RW rightly notes, they’re not ALL-IMPORTANT and doctors and pharma and policymakers should not worship them. We all know what statistics can not only demonstrate but also what they can obscure.

(3) absence of evidence in RCTs is not evidence of absence of benefit.

(4) if you are intent on finding a conclusion that fits your pre-existing views or experience, you’ll find it. This applies to someone like me, who might want to explain away the minimal evidence for antipsychotics as statistical mumbo-jumbo and not part of “real life practice”, or to someone who is committed to the antipsychiatry movement. If I have to be fair, so do you.

(5) We’ve all known for a very long time that people are complicated and any single explanation of us is doomed. It was true for demonic possession, ill humors, witchcraft, misplaced uteri, psychoanalysis, chemical balances….Let’s all strive to be humble

Report comment

Thank you for writing, and for your thoughts. The “let’s all strive to be humble” should be a motto in all of medicine, given its mysteries. Your voice is welcome here, and if you would like to write a blog for us that expands on your thoughts here, that would be great. Perhaps you can explain how absence of evidence in RCTs is not evidence of absence of benefit . . . I think that would be of much interest, in part because psychiatry, as an institution, is always citing rcts as evidence of benefit.

Report comment

Thanks for this. I will seriously consider your invitation to write a blog, and I feel honored that you’ve asked. Such a project is something I have considered before, and this is an inviting door to walk through.

Report comment

I have noticed accusations of a conspiracy, loose as it may be, including, apparently, everyone but me. I’ve been told tht the mentally ill commit fewer crimes per capita than the general public. None of my patients have become criminals (committed a crime) as a response to starting any medication. Could somebody point out, with some sort of documentation, one of these cases? I’m starting to feel left out, like I’m not allowed to have lunch with the cool kids and nobody tells me that there is a cafeteria let alone where it is. Not one member of this worldwide conspiracy has even hinted to me the existence of such an entity. Maybe it’s my breath or that my mother dresses me funny. Is there a secret handshake? If you’re one of these folks (you must be, because you’re apparently ubiquitous) please contact me and at least give me a chance to decide whether I want to join or not. If there is such a powerful nefarious ongoing genocidal plot, how did it miss those exposing it? Why are there any people seeking help for what they think may be mental illness (I don’t think the conspirators bring them in from the street. That would be noticed as suspicious.) left? Just curious. But, seriously, where can I join?

Report comment

I don’t think it’s a conspiracy. It is simply a convergence of massive monetary conflicts of interest, which cause the “thought leaders” to support things that are not scientifically sound. This doesn’t require a conspiracy, merely a strong enough cultural agreement such that those questioning the status quo can be blackballed or scapegoated or ignored. Hence, when real science shows that disability rates have gone UP since we started using psychiatric drugs, those who are so strongly invested in the system (psychiatrists, drug companies, lobbyists, parent groups, etc.) go into high gear coming up with excuses or alternative explanations for the obviously poor results. This is not by some massive conspiratorial plan, but simply because folks who are invested in the system have a lot to lose if they admit their diagnose-and-drug paradigm doesn’t really work very well in the larger scheme of things.

Let’s take “ADHD” for instance. The science shows there to be no single consistent “cause” for “ADHD”, in fact, there is not even a consistent way of diagnosing it. Additionally, there is little to no evidence that ANY long-term outcome is improved by stimulant “treatment” in childhood, in other words, the “unmedicated” do just about as well as the “medicated” children (and in some studies, better). Now if this were accepted, a number of things would happen. A) A giant industry would be threatened, as billions of dollars are yearly spend on stimulant drugs and on “specialists” who supposedly know more than you or I about “ADHD,” B) Doctors and others who regularly “diagnose” “ADHD” would have to admit they don’t really have the answers, and would lose professional prestige and clients, and c) teachers, parents and other adults would have to do the hard work of figuring out in each case what the child needs to be successful, and in the case of schools, possibly may have to reorganize the whole effort on new principles, which again means admitting the status quo is wrong, which harms reputations and costs some people their jobs. So we see that ALL of the above participants, without having to conspire at all, have a strong investment in believing that “ADHD” is a real “brain disease” and that stimulants provide successful “treatment,” even when they know the scientific data does not bear out their approach as successful. So, not a conspiracy, merely a convergence of professional-centered conflicts of interest that prevents those invested in the system from really examining whether it is helping or harming or doing nothing for their clients.

Report comment

” If we stop the med and the patient gets worse, and then we resume it and s/he gets better, tough to insist that the med is useless.” But this discounts the possibility of dependence, where things are expected to get worse upon withdrawal and to get better when resuming, just like meth or heroin use. Unless that possibility is taken into account, the fact that someone worsens when discontinuing a particular drug can not be honestly interpreted.

Report comment

Thanks – I’m being very careful with my words, and I’m not therefore stating that the supposed therapeutic action of the drug MUST be the reason for this scenario. Similarly, you’re raising the hypothesis that it’s a dependence-withdrawal phenomenon that explains it must be, to be fair, an unproven ( and maybe unprovable) assertion. There is not, to my knowledge, much to support the rapid development of withdrawal and dependence in the short-term; not saying never, but in my scenario, my opinion is that the therapeutic action of the drug is just a more likely explanation. To me, it’s hard to “un-see” what I’ve seen many times and discount that the meds are doing some good. Even if it were a dependence-withdrawal matter, if the patient is better ( and we are in agreement on that), it would not be a reason to say “let’s stop it” unless we had something demonstrably better to offer.

Report comment

I did not mean to imply that psych drugs have no use or can never be helpful. I merely want to debunk the very common myth that a return of symptoms when stopping the drugs means that the person is “relapsing.” There is plenty of evidence that at least with long-term use, withdrawal (euphemistically called “discontinuation effects” by some) is very common and can be debilitating. To dismiss this possibility has been the habit in the field for decades, and it’s only recently that this phenomenon has started to be given some credence, at least for antidepressants. But it is still common to mistake withdrawal effects for “relapse,” and that was my only point, that we must not assume “relapse” when withdrawal is a possible and in many cases much more likely scenario.

Report comment

Yes, and I’d add that the symptoms of withdrawal and what we’ll call relapse can overlap and confuse everyone. more typically, I’d say that it’s possible to distinguish between the two if you take the time and not just assume it’s one or the other.

Report comment

“To me, it’s hard to “un-see” what I’ve seen many times and discount that the meds are doing some good.”

Do you mean that if someone is dulled, zombified, detached from themselves and not able to feel anything deeply due to whatever was prescribed and as a result there is less visible agitation, less verbal expression of say, unusual beliefs, fewer behavioural outbursts and more passive compliance, then the meds are doing some good?

Report comment

not by a long shot

nor is that anything close to what I was saying

I’m sure you know that your question is not exactly worded to serve any constructive purpose, and I don’t see why you would attribute evil intent to someone you might only disagree with

Report comment

I am sure you know that so-called antipsychotics do exactly what I described and hence my question about how do you measure the good that they do.

Report comment

Thank you for you nuanced opinion.

As a mother of schyzophrenic and Asperger adult now 40 year-old I still wonder.

Because I remember the horrific times I had to go through while my son was not taking medication.

Now, he takes them but wants to stop, again.

I could not live again the constant fear of being killed by my son. I could not live next to the monsters, the voices and the suffering he was enduring through his imagination when not taking his medication. He told me that voices had told him to kill me. The voices are still there, even though he has been taking medication for four years, more or less.

So, I will let him decide but told him that I couldn’t live with him if he decides to stop taking his injections. He would be on his own. And that saddens me.

Report comment

How exhausting and frightening for you ( and him as well, in a different way).

I’d hope that he can ( if not already doing so) develop some non-medication ways of managing the voices. If he’s living under your roof, I would go as far as saying that he has a moral obligation to protect you whether he takes meds or not. I wonder if it’s workable to strike a deal of sorts in which he, say, stops them for x amount of time and then you two agree to re-evaluate how it’s going. It’s fair, in my view, to look at this as a kind of negotiation.

I wish you well.

Report comment

“We all know what statistics can not only demonstrate but also what they can obscure.”

Really… and just whose “we” are you talking about? The unbiased field of psychiatry?

Report comment

“We” includes psychiatry but not only.

Psychiatry has its biases, for sure, and we have to acknowledge them.

I’ve yet to meet anyone – anyone – who lives a bias-free life, so in that sense, we’re all in the same boat.

Report comment

Well I got hospitalized 3 times in a psychiatric ward, everytime in the clinical record was missing symptoms and I had a differente diagnosis everytime like the second time they wrote psychosis even though I never expericed it in my life. The 3rd time was a DSM behavioural diagnosis with more details (not part of the diagnosis) like: “with notable schizoid and paranoid elements”, obvioulsy based on nothing but their opinion(even the code of the diagnosis with it). You see the power of psychiatry lies on mocking people like this and even involuntary hospitalizing people because we insulted them as I did and It’s the reason I was put in psychiatry world. I missed the change to prosecute them and the time to do so expired because I was a teen back then, and I have no money.

It also very diffcult anyway because you will start, by defending youselves, by blaming the vicitim as they are legit “metally ill” as they are born with a defect in the brain, even though for ANY and EVERY psychiatry diagnosis there is no biomaker and known patology to be confirmed. I was 15 and asked the psychiatrist a document to not do physical education in school and she was down with it, but in exchange with a prescription of Antypsichotics to a teen and was off label too because the diagnosis was the behavioural one. Even giving it everything for free to me, and because of this I think there is an incentive to precribe to many people as possible even though she was a public psychiatrist working under the State; all this in Italy. And according to the clinical record, to torture me and making me disable, they spent nearly 4000 euro for 4-5 days of hospitalization. Surely, the staff was the ones to gain from it, they consumed all that money with hypocrisy. The lack of honesty is the problem with psychiatry and psychiatrists, and the fact that you have too much power. Even if you are a ” show precriber doctor and judicious” doesn’t change the facts that by telling people that are sick, as mainstream psychiatry do, like the pubblic perception is, you are lying and missleading, taking any psychotropic is like drinking a tonic or taking painkillers, but you don’t say that. It has to do with the legimacy of psychiatry as a medical field: if you are just handing out synptoms-masking drugs or behaverioral-controlling drugs, the interest will be not the health of the patients and so every involuntary hospitallizations will be Costitutional illigal, and politically neutral in forensic psychiatry

Report comment

“If we stop the med and the patient gets worse, and then we resume it and s/he gets better, tough to insist that the med is useless.”

Let me explain this sentence briefly. I hope it changes your mind.

1) Psychiatric drugs only numb healthy brains.

(That is, it does not and cannot cure any mental illness; it only numbs healthy brains. Because all psychiatric drugs have effects similar to those of illegal street drugs. Every psychiatrist knows this fact. These are not real ‘medical drugs’ but ‘legal’ street drugs. When healthy brains are numbed, what happens next?)

2) When healthy brains are numbed by psychiatric drugs, people experience a ‘calming down’ similar to a ‘fake recovery’.

3) Patients, under the effect of this calming down, fall into an illusion of ‘Wow, there is a world! Look, this psychiatric drug worked!’

(This situation is more like the situation of people who act with effects similar to those of illegal street drugs. Psychiatrists also try to convince people by saying things like, “Yes, look, it worked. These psychiatric drugs are a miracle,” at the expense of their ability to continue their profession. But they do not explain to their patients and their families the mental and physical deaths that may occur in the future (the very serious effects of psychiatric drugs). He hides and conceals these. When the patient’s brain is chemically damaged, he blames either the patient or any underlying illness/disease. In this way, psychiatry and psychiatrists acquit themselves (and protect themselves). What happens happens to ‘the patients and their families’. Those who die remain dead. Those who are injured (disabled) remain disabled.)

4) When patients remain on psychiatric medications for long periods of time (often months and/or years)…their healthy brains become permanently chemically damaged (permanent chemical brain damage).

(Permanent chemical brain damage is very different from physical brain damage. While it is possible to detect physical brain damage with various radiological and biological tests (such as MRI, ultrasound, X-ray, etc.), it is extremely difficult to detect chemical brain damage with such tests.

Because the natural chemical structures of healthy brains are damaged by the chemicals of psychiatric drugs, causing the natural chemical structure of the brain to change. The natural chemical structure of the brain is filled with the toxic chemicals of psychiatric drugs, and the brain is invaded with unnatural (artificial) chemicals. This chemical invasion disrupts the natural structure of the brain and usually after long-term (months and/or years) of psychiatric medication use, the brain chemical structure STOPS; in other words, the brain goes bankrupt.

The vast majority of people who have to stay in mental health units (such as mental hospitals, psychiatric hospitals, rehabilitation centers, nursing homes, and care homes etc,) until they die… are full of people who have suffered the chemical brain damage described above (i.e., whose brains have failed due to psychiatric drugs).

Mental health units such as “mental hospitals, psychiatric hospitals, rehabilitation centers, nursing homes, care homes” are full of people who have to stay there until they die (whose healthy brains have been destroyed by psychiatric drugs). In other words, they are full of people who have suffered the chemical brain damage described above, whose ‘brains have been destroyed by psychiatric drugs’.

Chemical brain damage is not visible like physical damage; it is invisible. So…

Physical brain damage is VISIBLE.

Chemical brain damage is INVISIBLE.

Chemical brain damage (chemical lobotomy) is invisible, so it may not be possible to detect it with radiological and biological tests. This benefits both mainstream psychiatry and the psychiatrists who serve it. It allows them to prescribe more toxic psychiatric drugs to their patients.

***

As a final word.. Mental illnesses are not in the brain; they are something in the person’s own soul. You cannot treat something that is not in the brain. Psychiatric drugs do not and cannot cure mental illnesses; on the contrary, they create them. They also cause various fatal physical and mental permanent illnesses and disorders.

A SPECIAL QUESTION;

“If psychiatric medications work, why do patients have to take their psychiatric medications until they die?”

This is a question that no psychiatrist in the world has ever been able to answer CORRECTLY and LOGICALly. They come up with various excuses, but none of them are CORRECT and LOGICAL ANSWERS.

Constant excuses, constant pretexts… Best regards.. 🙂 E.Y.

Report comment

There is something I forgot to mention here… Chemical brain damage is invisible and is not detected by radiological or biological tests.

Yes, it is, but..So, there are studies, research and articles that psychiatric drugs cause brain damage, what are these? So.. Why do other honest psychiatrists, doctors, researchers, etc., like Psychiatrist Prof. Peter Breggin, claim that ‘psychiatric drugs cause chemical brain damage’? Because they probably have evidence, footage.

Probably… Chemical brain damage from psychiatric medication can be ‘chemical brain damage’ that has turned into physical brain damage. If chemical brain damage turns into physical brain damage, this could be a possibility. So… This brain damage can be revealed with radiological and biological tests (such as MRI, ultrasound, x-ray).

Let’s explain it this way… In fact, chemical brain damage can be detected with ‘radiological and biological tests (RB-T)’. However, this requires a ‘two-stage test series’. RB-T tests are needed before and after using psychiatric medication.

RB-T tests performed only after using psychiatric drugs will not give accurate results. Before that, RB-T tests should be performed before using psychiatric drugs. Differences and changes are detected between the two.

So.. In fact, radiological and biological tests could detect changes in the chemistry of the brain. (In fact, chemical changes in the brain are chemical imbalances.)

In one study… (You know this too.) Before using psychiatric medication, patients’ brains (brain chemistry) appeared healthy. After using psychiatric medication, there were changes in the chemical structure of the brain.

So.. The patients’ healthy brains (the brain’s natural chemical structure) were altered after the use of psychiatric drugs. (Chemical change in the brain = Chemical imbalance in the brain.)

Probably… Mainstream psychiatry and psychiatrists have known for a long time that psychiatric drugs create chemical changes (i.e. chemical imbalances) in the brain. And they used that information for their own benefit. That is, they used it for many years in a misleading way by suggesting that ‘mental illness’ is caused by a chemical change (i.e. imbalance) in the brain.

In this way, they have deceived people, governments, societies, patients and their families for years. In this way, they have prescribed toxic psychiatric drugs to billions of people around the world. They have tried to create chemical imbalances in the healthy brains of billions of people. And they have succeeded.

How many billion people were killed and maimed (injured) by psychiatric drugs between 1950 and 2025? Indeed, “Psychiatry is a death industry.” Point..

Best regards, 🙂 Y.E.

Report comment

Thanks again

It’s hard to go point-by-point with your comments, and I don’t have any way to know about your experiences ( as is true for you about me), but I gather that you see psychiatry and psychiatrists as more motivated by evil impulses than I do. I disagree, which also allows me to say that bad things have happened at the hands of psychiatry, and that some were indeed motivated by malice or greed or other evils. We can agree on that and perhaps differ on the extent of it. Fair?

Report comment

Thank you for your response. As far as I can see… As a psychiatrist of 40 years, you have also tried to respond to every commenter here. If your goal is to tell everyone that psychiatric drugs are very beneficial, keep doing it… eventually you will realize ‘how wrong’ you are. I hope so..

I didn’t quite understand what you said in your comment. You are speaking in philosophical language. I am not very good at speaking in medical language and/or like a philosopher, as psychiatrists, doctors and other experts do. I directly state whatever truth I have learned in my research. I do not hesitate to do so.

If you want ‘evidence’… You can read and learn the evidence and facts that Peter Breggin, Peter Gotzsche, Robert Whitaker, Joanna Moncrieff and all the other researchers who do not serve mainstream psychiatry, such as psychiatrists, psychologists, doctors, journalists, etc., have revealed in their books.

If you have read and think these are ridiculous… you can share your experiences and knowledge with MIA and/or publish a book. If you have scientific studies, you can publish them in scientific medical journals.

If you do these, I am sure there will be many psychiatrists, doctors, psychologists, journalists, researchers, etc. scientists (who do not serve mainstream psychiatry) who can answer you. You will probably be faced with ‘many studies’ that will refute your data. I recommend that you be prepared for these.

***

Yesterday I went to the nursing home where my brother was staying. My brother’s condition seemed to be getting worse. Psychiatric medications were starting to make my brother’s healthy brain worse. Not only psychiatric drugs but also psychiatrists are primarily responsible for this.

While children’s ‘childhood behaviors’ can be corrected with a number of non-drug treatment methods, psychiatrists immediately resort to psychiatric drugs and if they do not work, they prescribe different psychiatric drugs over and over again, so there is a high probability that children’s healthy brains will suffer chemical damage in the future.

Probably… Piciatrists serving mainstream psychiatry seem to be working hard to damage (chemical brain damage) the healthy brains of not only children but also adults.

***

The fact that it is the psychiatric drugs that cause brain damage in people who are in mental health units (who have to stay there at least until they die)…

Probably… As a psychiatrist for 40 years… you know that in mental health units such as ‘mental hospitals, psychiatric hospitals, mentally retarded rehabilitation centers, nursing homes and care homes’… the thing that causes people (at least the vast majority) who are people who have to stay there until they die to become like this (i.e. experience chemical brain damage) is psychiatric drugs.

If you don’t know, I recommend you learn. We are sure that the vast majority of mainstream psychiatrists and psychiatrists serving mainstream psychiatry know these.

***

In fact, states need to investigate and uncover what might be causing people in mental health units to come to this state.

But for this… There is a need for honest psychiatrists, psychologists, etc. who do not serve mainstream psychiatry. There is a need for honest doctors, researchers, scientists, etc. who do not serve mainstream medicine. There is a need for honest journalists, researchers, writers, etc. who do not serve mainstream media. There is a need for lawyers, prosecutors, judges, etc. who do not serve mainstream law. There is a need for politicians, politicians, bureaucrats, etc. who do not serve mainstream politics. There is a need for honest people, NGOs, civilian researchers, intellectuals, etc. who do not serve mainstream civil society organizations.

These honest people need to come together and determine what has brought all the people in mental health units to this state and share it with the public. You can imagine that the outcome will not surprise me or the scientists who have been trying to express this situation for years. We can think that the outcome, at least the vast majority, may be ‘psychiatric drugs’. We may see that ECT and other harmful psychiatric treatments are also involved in the result. There may be other reasons. However, for this to happen, it is necessary to investigate and reveal whether the cause of these people’s brain damage occurred before or after using psychiatric drugs.

Am I daydream too much? I hope that if mainstream psychiatrists had the same daydream, they would do something to prevent iatrogenic harm to billions of people around the world.

Probably… Mainstream psychiatry and mainstream medicine will not allow such research in mental health units, as they know that the result may be against ‘psychiatric drugs’. All mainstream organizations will agree.

Because the criminal does not want his guilt to be revealed. If the criminal has a conscience, he will admit it anyway. If he does not have a conscience, he either remains silent or continues to lie and deceive people. Best regards..

Report comment

Richard, It’s hard to be a symbol for a section of healthcare that really hurt and harmed as well as helped. As a person who has worked and was a patient after primary snd secondary trauma I really think psychiatry went down a very deep and dark hole with just the use of bio psychiatry . Judith Herman PhD and Peter Levin PhD and Selma FrsibethMSW works among others on trauma almost out the door completely. I saw the change 1980 and on. When I was in country ( those horrible years) and half of my reason well how bad is it. And it was truly horrific.

And if you look at the entire history from Rorsach to Bedlam( they gave tours on certain days to make mi ey) it was ranges of issues with more bad then good and isms all over the place. Eve Ewings’s Original Sins gives a standout look at the origin of the Standford Binet Test and how it was used in WWI.

What is really needed is not just your voice or others. What is needed is an apology from APA, APA, NASW, AMA etc for an apology like the Canadian and Australian governments gave to their indigenous populations. Ireland has done that as well not sure about the church but they are exhuming the perhaps 800 infant/ child bodies buried in a sanitary sewage pit.

And orphanages, foster homes , residential treatment, even elite boarding schools all have stains and sometimes blood as well . The concept of healing and healers is very very ancient. We are so imperfect at best because we lost so much past knowledge. amAnd the only way we humans learn is through mistakes. When we let the mistakes go and continue in great denial then we hurt all of us. And in that hurt only more hurt. Truth telling takes courage. Apologies done well with amends take courage but it can be done. The world needs a litany a year of reall apologies.Please consider getting peers to look into this and read history on colonialism – all the isms and how psychiatry played a role.

Report comment

You’ve put a lot of thought into this, and clearly have been through even more.

I agree that truth-telling takes courage, but not only courage.

I’m trying to do my part without getting too far ahead of myself.

Thanks

Report comment

Psychiatry in Nazi Germany and the USSR supported and obeyed the dictates of brutally coercive regimes.

Are mental health professionals in the U.S. and other western countries who knowingly disable the brains of their clients (i.e. victims), many of whom are young children, rebellious adolescents, and vulnerable elderly patients in nursing homes, any better than Hitler’s and Stalin’s willing enforcers of social control?

Yildirim is right: we are witnessing psychiatric genocide on a massive worldwide scale. This outrageous situation may not be due to a conspiracy, but its origins and consequences should be obvious to anyone not deluded by the lies of Big Pharma and its venal, indifferent, or corrupt apologists in academia, regulatory agencies, the media, and other institutions.

Report comment

Dear Yildirm, E, I do love your writing, but don’t you agree that there is and can be nothing that is not “God,” or “The Great Mystery,” so that the ONLY thing which “God” cannot do is to exist, in the sense of standing out from, ex-istere?

The answer to

“How all many of us all are all in this altogether?” may seem obvious, but the “Why?” less so.

And so, I have asked many strangers, all of them perfect (at the very, very least),

“What is The Meaning of Life?” (- obviously, the first question to be answered at any seminary and school of psychiatry or of psychology – OR of medicine, or nursing, or…….)

They have not been quite unaminous, but the most common reply by far has been either,

“Huh?”

or

“What?”

One lady, with a loud laugh, then told me that, “The lessons git harder until we git ’em,” convincing me that this is so, even if the lesson is always the same one in different guise.

One guy unhesitatingly told me that it was forty-two, and another either “Do the next best thing” or “Do the next-best thing,” and I interpreted this as The Great Mystery awakening me to the realization that I had always and ever been doing, does as She clearly needed me to do, the next next-best thing,” even if right now I am not so sure that I should already be out on my bike instead of typing this but, come to think, I should probably have been letting Tiger out or that fresh air – yum – in.

I was already 49 when that Irish healer guy – the one who insisted that he had not healed my veterinary colleague of her years-long fibromyalgia after she had almost been dragged to his door, kicking and screaming and protesting that that she had absolutely no faith in any such quacks and charlatans as were called “faith-healers: “She is a very strong-willed woman; she healed herself,” he had explained to me.

When this guy had refused any payment from me for speaking for ?90 minutes or so down the phone with another female vet colleague with fibromyalgia (I think), and I asked him why, he simply told me whatI already knew but had forgotten, just like you may have done, too:

“The only reason we are on [did he say “put on” or come to?”- I can’t say, but does it matter?] this planet is to help each other.”

I was, as I say, 49, and, as you may know, some say that something mighty significant happens to a person every twelve-and-a-quarter years (on this planet), and this statement instantaneously filled innumerable dangling equations for me, Q.E.D.

I am guessing that William Shakespeare might have agreed with this, and his Hamlet, too, and maybe even his King and Lady Macbeth, and Carl Jung and Thomas Szasz and, if it had been put to him before he led us all astray Descartes, too?

It’s interesting, I find, that, once we apply this formula, all such “disorders” as lack or loss of hope or of humor, all grief, all distractibility, all procrastination and all that makes Life seem tedious is instantly explained, so that all chaos become cosmos; all seeming disorder, order, just as Carl Jung promised us – or so I find.

You, please?

And now, I guess the next next-best things I can do include closing that door and hitting the road, again.

Wishing everyone their best day, ever, yet, and almost more mirth than we can almost cope with,

Tom.

Report comment

Oops, my very sincere apologies, but no regrets, Yildirim E: My spellcheck obviously somehow overlooked my accidental omission of that middle i from your name.

Trying, as I do to believe that to err is divine, to forgive, human, as these worlds must all be unfolding as they should, and to make lemons from lemonade, to “lean into the difficulty,” and to know that The Obstacle IS the Way, at least until the lessons get easier again, and then become pure joy, again, I naturally looked up your name and was told it means thunderbolt or lightning, not very, very frightening, but very, very speedy and, knowing that you are not so slow and that we must all get the rightest names, after all, G. K. and his comments on Joan/Jehanne came instantly to mind, as well (ok, the next instant/s) as did the omission from my previous submission of how Life Gets Tedious (and gits teejus, too) when we feel that we are making so much less progress that we can once we can figure out precisely what the next next-best thing for us to do, or say, or think or be is:

Joan of Arc – Maid of Heaven – G. K. Chesterton on Joan of Arc https://share.google/qRKtqXfsnkaoqUKf1

Life Gets Tedious Don’t It https://g.co/kgs/E9ujwfG

Renewed apologies, Yildirim E., and very, VERY best wishes to you, to even, and to me.

Tom.

Non, je ne regrette rien https://g.co/kgs/1a97FUM

Report comment

Thanks, Tom Kelly… Have a nice weekend.. 🙂

Report comment

Thank you, Yildirim, and back at you!

I believe that what I have attempted to articulate is that the good news of Jesus, as of every other great spiritual teacher/prophet in human history has been that we need “only” make conscious the (very stubbornly) unconscious within us all in order to appreciate that we ourselves, just like everyone else that ever was, have always been doing our very best – at the time.

This realization renders the notions of deliberate “sin” and of hapless, unavoidable “mental disorder” and “personality disorder” ludicrous.

But the somersault in thinking or transformation of consciousness necessary to allow this insight – even for a moment – has obviously been, with few exceptions perhaps as rare as early bloomers in a vast field of sunflowers – more than we humans have been capable, with the rarest of exceptions, such as Lao Tzu, the Buddha, Socrates, Jesus, Rumi, “Julian” of Norwich, Meister Eckhart, Teresa of Avila, Shakespeare, Mary Wollstonecraft, Carl Jung, Niels Bohr, Albert Einstein, John Steinbeck, Eckhart Tolle…:

“Theologians may quarrel, but the mystics of the world speak the same language.” – Meister Eckhart.

You do not become good by trying to be good, but by finding the goodness that is already within you, and allowing that goodness to emerge. But it can only emerge if something fundamental changes in your state of consciousness. – Eckhart Tolle, “A New Earth: Awakening to Your Life’s Purpose.”

Until now, “Judaeo-Christians” (or “Judaeo-Paulines,” as I call them) seem to have by and large failed to perceive the vast gulf between the Greatest Good News Ever message of Jesus and the Same Old Same Old, Keep- those- Commandments message of Paul, while our three major religious traditions, the Abramic or Abrahamic ones, deriving from a guy modern psych pharmacology must label a murderous paranoid schizophrenic, preach of a creator God of this cast universe, at the very least, whose entire day seems to have been ruined over and over again for Him by His having to contend with the disobedience and disrespect of His human children…

“Oh, what idiots we all have been. This is just as it must be.” – Niels Bohr.

“I hold that a writer who does not passionately believe in the perfectibility of man, has no dedication nor any membership in literature.” – John Steinbeck.

John Steinbeck – Wikiquote https://share.google/l7mkB59HUKSfwAQid

https://youtu.be/7SKEODtaQUU?si=ndoBUN5xV-_TDvOG

Because we remain perfectible, we human beings remain at least infinitely more than any human conception of perfection, or vice-versa, or both.

And because we are beings, we can never cease to be nor have begun to be.

Apparently, Jesus saw this but saw, too, that his failure/inability to make this clear must mean thousands more years of confusion and of dissent and of, as at least two Upanishads had put it long before him, of blind leading blind.

“Be ye therefore perfect [sometimes rendered as “whole”], even as your Father which is in heaven is perfect [again, or “whole”]!” – Jesus of Nazareth, at least according to Matthew, 5:48.

“Do not think that I have come to bring peace to the earth. I have not come to bring peace, but a sword. 35 For I have come to set a man against his father, and a daughter against her mother, and a daughter-in-law against her mother-in-law. 36 And a person’s enemies will be those of his own household.” Jesus, acc. to Matthew, 10:34-36.

“Do you think that I have come to give peace on earth? No, I tell you, but rather division. 52 For from now on in one house there will be five divided, three against two and two against three. 53 They will be divided, father against son and son against father, mother against daughter and daughter against mother, mother-in-law against her daughter-in-law and daughter-in-law against mother-in-law.” – Jesus, acc. to Luke 12:51-53.

Gospel of Thomas,Saying 16:

‘Jesus said, “Men think, perhaps, that it is peace which I have come to cast upon the

world. They do not know that it is dissension which I have come to cast upon the earth:

fire, sword, and war. For there will be five in a house: three will be against two, and two

against three, the father against the son, and the son against the father. And they will

stand solitary.”

I am not asserting that any such gospel writings are entirely accurate, nor even that this Jesus even lived, but I am suggesting that failures to understand that we are all absolutely equal – as immortal beings – has been the cause of our hostilities and of our lack of “humanity” towards one another, and that this Jesus may have resigned himself to this fact and to its continuation in spite of ALL his own very best efforts….but not of OURS!:

“Verily, verily I say unto you, he that believeth in Me, the works that I do he shall do also; and greater works than these shall he do, because I go unto My Father.” – John, 14:12, “My Father/Our Father/Heavenly Father” representing Formless Consciousness.

Here’s hoping, and to trusting IN Hope!

Thank you, again, Yildirim – and sorry, again, for “my” multiple errors!

Tom (Kelly).