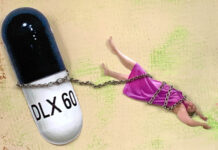

It is hard to believe that a year has gone past since I posted Playing the Odds: Antidepressant Withdrawal and the Problem of Informed Consent. I want to thank all of you who reached out to me to through email, phone calls and office visits to share your thoughts and experiences with me. It was informative and enlightening, and bought to me a greater understanding of the problems related to long-term SSRI toxicity.

The feedback I received after posting ‘Shooting the Odds’ underscored the more controversial aspects of SSRI toxicity. Common themes concerned the abrupt onset of new symptoms 3 to 12 months after stopping the drug, reinstatement of the drug failing to help withdrawal related symptoms, the possibility that withdrawal-related symptoms can persist indefinitely and concerns about using benzodiazepines to help with tardive akathisia.

My patient population suggests that the problems relating to stopping SSRI antidepressants (which also includes SNRIs) must be widespread, and often severe. It used to be that people with these sorts of problems contacted me only because they were aware of my subspecialty interest in this area. Increasingly I am seeing patients who contact me for problems related to stopping a SSRI without knowing anything about me at all, because they found my name in their insurance plan provider list and I am nearby. This didn’t happen a few years ago. It appears that problems relating to stopping SSRIs are widespread and accelerating.

Since my last blog the patients whom I have seen and people I have spoken with reinforce the notion that withdrawal-related symptoms may show up abruptly months after stopping the drugs. I recently saw a patient who stopped an SSRI rapidly after a 15 year cumulative exposure. Surprisingly, there were no immediate withdrawal related symptoms at all. Despite feeling well, the patient wanted to know if they were in danger because there was no tapering and wondered if it would be safer to restart and then taper the drug

This was an interesting question. It appears that the immediate onset symptoms – zaps, vertigo, vivid dreams, flu like symptoms and mania, are somewhat different from the late onset symptoms which are collectively referred to as tardive akathisia. I have not, however, seen late-onset symptoms that present as zaps and vertigo. The immediate and late-onset withdrawal-related symptoms may have different mechanisms of action. While tapering clearly reduces the immediate onset symptoms, it is unknown whether tapering has any effect on the late onset symptoms. Besides this one patient, I have seen other patients who had no immediate withdrawal related symptoms and subsequently went on to develop late onset symptoms.

This particular patient did well for 4 months and then after their dog died, they had a very abrupt onset of a severe, almost intolerable depression which remitted when the drug was reinstated. When the patient first presented in the office, I could not see any benefit in reinstating and then tapering when the patient was already feeling well. Reinstating can sometimes be harmful. In retrospect I wonder if tapering could have been beneficial.

This illustrates another finding concerning the late-onset symptoms. While it is difficult to determine cause and effect, to some extent it appears that the late-onset symptoms are related to an excessive reaction to a stressor. Another patient had late onset symptoms of severe anxiety after a fairly mild earthquake. The patient commented to me that despite having been through earthquakes in the past, they had never had a fear of earthquakes before. It seemed out of proportion to the patient.

My experience is that reinstatement of the drug shortly after onset of late withdrawal symptoms works well. I typically reinstate slowly. It appears that the duration of drug use is unrelated to success of reinstatement. On the other hand, the longer the late onset withdrawal symptoms persist before reinstatement, the more likely it is that reinstatement is not going to help and may hurt. I have seen patients who suffered tardive akathisia for over a year, and then reinstated only to find that it made matters worse.

Recently I saw another patient, a 32 year-old person with a 7-year exposure to Celexa and Lexapro. We successfully tapered off of the drug and stopped it completely. They had minimal acute withdrawal symptoms, but had panic attacks at 7 months after stopping. The onset of the panic attacks coincided with an insurance company physical which disclosed high blood pressure and possible kidney problems. There was also severe ongoing generalized anxiety, racing thoughts, akathisia and insomnia organized around fear of kidney failure. They were prescribed Xanax 0.5 mg which was to be taken no more than twice a week to prevent dependency. The drug was taken infrequently and 30 tablets lasted for 7 months. By 14 months there were no further panic attacks, anxiety or akathisia and there were no panic attacks at follow up 24 months after stopping. The patient commented that they felt like their “life was starting” since stopping the drug, adding that deeper and more meaningful emotions and interpersonal relationships were experienced. This person also had sexual dysfunction for the entire 7 years of having taken the SSRI which resolved completely on cessation and resulted in a much better relationship with their partner.

This case illustrates a few notable features of stopping SSRIs. I wonder if the late-onset symptoms relate to overreaction to stress. The abnormal blood work preceded the anxiety as did the earthquake in the other patient. Also, it is notable that the late-onset symptoms went away over a few months. This suggests that, at least in some patients, the late-onset withdrawal symptoms may be transient. If possible, waiting it out instead of reinstating may be the best treatment option.

However, it is difficult to not reinstate the SSRI in patients with tardive akathisia. The suffering of these patients is far more severe than what I see in patients who have disabling anxiety or depression unrelated to SSRI use or withdrawal. These patients are often on the edge of suicide, partially from the discomfort of the akathisia, and partially from a sense of deep, hopeless depression.

Besides reinstating the SSRI, the benzodiazepines can offer significant relief from the akathisia. The most intense criticism of my last blog came from people who were opposed to the use of benzodiazepines. At the risk of eliciting the same, vehement criticism, it is my opinion that benzodiazepines are a useful tool in working with tardive akathisia. Medicine is filled with imperfect choices, and this is one of them. Of course, benzodiazepines are problematic, but for some people with tardive akathisia, they are literally life saving. In the above patient, we were able to use infrequent doses of Xanax with good symptomatic relief and no dependency. I have seen two patients who had severe akathisia and took benzodiazepines with benefit, and became dependent on them. Still, these two were able to taper and stop them without incident years later after akathisia stopped.

I have been profoundly influenced by a patient I saw who had a state of tardive akathisia that was so intolerable that they were extremely suicidal. Valium was prescribed and when the dose got up to 90 mg of Valium they calmed down and suicidal thoughts stopped. Two weeks later, out of concern about the high dose of Valium, I reduced it to 60 mg, and the akathisia came back and the patient committed suicide. The patients with tardive akathisia are pretty much all suicidal to various degrees, and the benefits of benzodiazepines need to be considered in certain patients.

In 2012 a then 56-year-old person contacted me wishing to stop taking Effexor (150 mg) after a 14-year exposure. The older a person is and the longer the drug has been taken, the less likely the person is to successfully taper off the SSRI. After reading ‘Informed Consent’ and learning about potential difficulties ahead, the patient still wanted to try stopping Effexor. The patient had run out of medication, at times, in the past and experienced a number of unpleasant withdrawal symptoms. It was the withdrawal symptoms that convinced the patient that the drug is toxic and that stopping it was essential. We used the bead tapering strategy, where 5% of the beads from a 150 mg capsule are removed per month until 75 mg was reached. At 75 mg the tapering schedule was changed to 2.5% per month. Some months when things were particularly stressful the patient elected not to decrease the dosage. We are at 54 mg and the tapering continues at this time. To date there have been almost no withdrawal related symptoms. We are optimistic at this point. This is a good experiment in ultra conservative tapering, and may answer some questions about the value of tapering ultra-slowly in preventing both acute and late onset withdrawal symptoms.

The question that I am most frequently asked is whether tardive akathisia ever goes away. The answer is an ambiguous ‘sometimes.’ The general rule is that if the condition is showing any improvement, then it is likely that the improvement will continue. Improvement is not linear, and usually goes two steps forward and one step backward. Still, if the general trend is towards improvement, then continued improvement is expected. Sometimes it improves quickly, and remits over a few weeks or months. I have also seen a few patients who improved steadily and almost (but not quite) to baseline over 5 to 7 years.

It is a lot more problematic if there is no improvement at all or if the withdrawal symptoms are severe. If akathisia is severe and impairing, it is not something that can be just watched over for months and years, and my approach is to reinstate early on in order to restore well-being and functioning. If it is milder and more tolerable, but there is no trend towards improvement, decision-making is more complex. How long do you wait before reinstating? The longer you wait the less likely reinstatement is to work. Usually the trend towards improvement can be seen within the first month or two, but this is not always easy to discern when the course is erratic. For the patient with milder tardive akathisia the direction is unclear, but intermittent benzodiazepine use becomes a viable option.

When patients request help with SSRI toxicity, I ask them why they didn’t go back to their prescribing doctor and ask them to stop the medicine. The typical answer is not surprising: the physicians are frequently unwilling to stop the medications at all or insist on substituting a similar medication or an antipsychotic medication. You would think that a high-functioning, more-or-less asymptomatic person asking to stop medications would find their physician agreeable. My guess is that physicians do not stop the SSRIs because the physicians have already had a few difficult experiences with what can happen after stopping the drugs. I suspect that physicians want to think that the problems are not withdrawal-related, but a reappearance of the mythical chemical imbalance or a new onset of bipolar disorder.

When you stop to think of how many patients the average family physician or psychiatrist puts on SSRIS, including themselves, family and friends, and the long-term results of these prescriptions, the cumulative misery effect is so large that if the physician really became educated, then they would be unable to live with themselves.

SSRIs have now been on the market for over 25 years, and some patients have been taking them for that long. So a lot of the patients seeking to stop taking SSRIs have been on them for so long that the risks from stopping the drugs are significant.

It is difficult to imagine anyone performing scientific study to prove that late neurotoxic withdrawal symptoms will occur. Ideally, a control group of people who recovered from anxiety/depression with no medications would need to be compared with a similar group who recovered with medication and then stopped the medication as well as another group who recovered with medication and never stopped taking the medication. I don’t see this on the horizon any time soon.

What is going to happen at 30 years or 40 years of cumulative exposure? Similar to global warming, it is the sheer magnitude of the problem that may prevent critical analysis. In the meantime, getting this information to the public, such as in well researched books like ‘Anatomy of an Epidemic’ and the excellent work from RxISK is the critical first step. A decade ago patients were almost always insisting on an SSRI, but now a lot of patients know somebody who took an SSRI and went downhill rapidly and they are more interested in other treatment options. Let us hope that public opinion trends further away from SSRIs and the unproven benefits from psychiatric drugs in general and that research will be done to clarify just what these drugs are doing and what can be done about the adverse effects.

Generally you cannot undo physical damage to the brain that is why no one can expect to be whole after a drug has been administered. The tardive symptoms are forms of chronic traumatic encephalopathy and the whole structure and function of the brain has been modified.

People often cannot even tell they have been hurt because there is no error correction or checksum code in the brain. There is no before or after scans either, which is hard to do because technology currently disallows quantum copying of the brain. The level of damage is at the subatomic, atomic, and molecular levels, into the magnetic and electromagnetic and particle levels and ultimately into the physical structure and misgrowth and loss in the brain.

Once your memories and inbuilt functions are damaged you are damaged for good, like a piece of wood that rots and gets beat around, the original young structure can, the structure that took since conception to grow and form, cannot be put back into place..

Damn. . but people can try to recognize what they have lost, they feel it and experience nice it over time, and at that point the focus is in just not losing any more, by not using Tue drugs at all even to try them to see if they fix the problems. What yo can try is living a life like someone who just took a bullet hole in the head and doesn’t even remember what is gone, and use of physical and neurological rehab to try to rebuild and repair is useful. You have become a new split identity and you have to accept the loss, that you aren’t the same and never will be, but can become a new person living with the damage trying to pick up what’s left.

Report comment

If you don’t use an arm or leg for a long time , say it is in a cast, the muscles in it shrink from not being used.

When you take the cast off, you could say the leg/arm is broken forever, but with the discipline of daily exercise, the muscle in the arm/leg can grow back to near normal.

But it takes work.

What ever you chose to think of will stay in your mind. If you believe you are ill, you will look for signs you ARE ill. If you believe you are improving, you will look for signs of improvement.

Report comment

Todd, My friend, that is so much easier said than done. It sounds like advice coming from someone that’s been through it before. But i’m cursed with a analytical mind. So i’ll ask anyway: Are you speaking from first hand experience? Because if so then you are a helluva lot stronger than myself. Thank you.

Report comment

Generally you cannot undo physical damage to the brain that is why no one can expect to be whole after a drug has been administered. The tardive symptoms are forms of chronic traumatic encephalopathy and the whole structure and function of the brain has been modified.

People often cannot even tell they have been hurt because there is no error correction or checksum code in the brain to point it out, all you get is disturbed existence and memories that soon make sense or might never come to be realized about it. There is no before or after scans either, which is hard to do because technology currently disallows quantum copying and storage of the brain. The level of damage is at the subatomic, atomic, and molecular levels, into the magnetic and electromagnetic and particle levels and ultimately into the physical structure and misgrowth and loss in the brain.

Once your memories and inbuilt functions are damaged you are damaged for good, like a piece of wood that rots and gets beat around, the original young structure gone, the structure that took since conception to grow and form, cannot be put back into place..

Damn. . but people can try to recognize what they have lost, they feel it and experience it over time, and at that point the focus is in just not losing any more, by not using the drugs at all even to try them to see if they fix the problems (you merely begin to damage the damaged parts again, if you use drugs again). What you can try is living a life like someone who just took a bullet hole in the head and doesn’t even remember what is gone, and use of physical and neurological rehab to try to rebuild and repair is useful. You have become a new split identity and you have to accept the loss, that you aren’t the same and never will be, but can become a new person living with the damage trying to pick up what’s left..

I recommend physical excersise, massage, whole body vibration, mental excersises and steam room and hot / cold therapy. And living a stress free healthy life with proper diet.

No drug and no surgery is ever going to mend it. If quantum physics allows reshaping the brain into completely new structure that might to it, otherwise you accept it and live till death. Same as you would any other loss.

Report comment

Stuart

I applaud your efforts to help people deal with protracted withdrawal issues for SSRI related tardive dysphoria or tardive akathisia.

I was one of the people who was quite critical of your last posting especially regarding some of the vagueness concerning your use of Benzos. I’m ready to move on from that and address some questions regarding some of the new experience you are summing up about this difficult problem.

My main issue with the evidence presented about these case histories (above) is the very important information that is either left out or not gathered. I know that you cannot state everything in a single blog posting but how can we more deeply understand this problem without knowing the following information:

1) Do you know (with reasonable certainty) if your patients are using other mind altering substances such as alcohol and pot etc. on a regular basis? And, if so, how does this substance use effect their presentation of distressful symptoms or perhaps weaken coping skills in the long run?

2) Do you prescribe exercise, yoga, dietary changes, and meditation with the same IMPLIED authority and weight as you do the use of psychiatric drugs for help with these protracted problems?

3)Would you challenge those patients who only took the drugs you prescribed but avoided your other prescriptive advice (exercise etc., if given)) with the same concern as if they avoided taking the drugs you recommended?

4)Have the patients who have succeeded with fewer problems with withdrawal been those who have more consistently worked on the above mentioned coping mechanisms that involve both mental and physical skill building?

5) Are some of the patients who have suffered relapses or prolonged symptoms more likely to have experienced trauma in their past and how might this be related to their difficulties when presented with new stressors or “triggers” within their environment. Do we need to focus more attention on trauma recovery (even trauma at the hands of psychiatry) as part of this work around helping people with withdrawal?

6) Is it possible that the prolonged use of SSRI drugs lowers the frustration/tolerance level for enduring stress and requires extra work on the part past victims of these drugs to strengthen inner resilience and coping skills, especially those skills mentioned above and others? How can we create more favorable conditions for people to understand the value of these practices as we seek greater understanding of this problem?

On the issue of Benzo use: I do not have a position that they should never be used, but I think it would be more on the very rare occasion. Certainly Benzo withdrawal, itself, is often protracted in most cases. I would always be concerned that new Benzo prescriptions could create a whole new set of problems and may prolong protracted withdrawal problems. The single case that you presented of the person who carefully took Xanax with some success to help her withdrawal would seem to be an extreme exception. Xanax is so effective in the short term that the path of least resistance would be for most people to keep taking them to relieve very uncomfortable symptoms; tolerance come quickly and so does dependence.

Stuart, have you any experience, or do you know other doctors or patients who have had any success with protracted withdrawal from either SSRI’s or Benzos who have used Neurotin (gabapentum) as a temporary replacement and/or aid in hastening safe withdrawal?

Richard

Report comment

Richard,

You’re asking some good questions but in my opinion, one can still get withdrawal issues even if they have followed all the suggestions in your post.

What folks don’t seem to understand is taking these meds long term can do big time damage. Learning coping skills definitely doesn’t hurt anyone but if you just happen to be unlucky such as developing long term insomnia due to these drugs messing up your sleep cycle, it isn’t as cut and dried as you seem to infer in your post.

And before anyone says that causation doesn’t equal correlation, that is a fair point. But I know way too many people who didn’t have sleep problems prior to being on psych meds and developed big time problems after getting off of them.

Unfortunately, since psychiatry denies that this can occur, it will never be officially studied. Instead, people will be offered more sleep meds and the vicious cycle will continue.

Report comment

Agreed AA…withdrawal issues are a sort of injury and it doesn’t necessarily matter what one does if the nervous system has been injured. One of the most common causes, it seems to me, is a med merry go-round, often for many years…switching drugs, without tapering etc…a lot of folks go through such experiences before coming off and once the nervous system has been deeply jangled there seems to be some pain in coming off no matter what one does.

that said, everything Richard speaks to is of great importance. I do think that recovery needs to be multi-pronged and one needs to address multiple aspects of life and daily living…at various times more or less is appropriate or even possible. I couldn’t sit upright in bed for a couple of years…and that was just the way it was…I worked on other things besides exercise (for example)

I’ve since become a huge fan of yoga and it literally rehabbed me from complete muscle atrophy, up out of bed and into the world again. I can feel it healing my nervous system as well…it’s an astonishing process to be this sensitive to what is going on in our bodies…but that is what this process allows for.

Also, Richard…it’s clear to me as someone with a trauma history that the drugs actually create additional trauma, making those neuro pathways deeper and more intense…these drugs are, in fact, agents of trauma and so truly exacerbate pre-existing trauma issues…what that amounts to is that those of us impacted need, all the more urgently, to tend to those issues too. At this point I’m grateful to be able to heal so deeply and profoundly as a result of such excruciating rawness demanding just that…still the cost is ridiculously high and I would have liked another method had this all been understood and it’s why I’m so highly motivated to help others find other ways.

I could go on… but I’ll just share this:

Psychiatric Drugs as Agents of Trauma — “Drug Stress Trauma Syndrome” http://wp.me/p5nnb-6zY

Report comment

“I’ve since become a huge fan of yoga and it literally rehabbed me from complete muscle atrophy, up out of bed and into the world again. I can feel it healing my nervous system as well…it’s an astonishing process to be this sensitive to what is going on in our bodies…but that is what this process allows for.”

Wonderful (and inspiring).

🙂

Report comment

Hi Richard:

Your questions are thoughtful and ones that I have considered. First off, you need to know that I don’t prescribe medications all that often to anyone in my practice, and that patients coming to see me for withdrawal problems are mostly people coming to see me because they have already had a bad experience.

*Some of the patients smoke pot, but none are drinking or using other recreational drugs.

*Generally I do not prescribe any medications for people while they withdraw or who have had problems stopping – except if suffering is extreme (and sometimes it is very extreme). The severely ill are not people who are capable of exercising or meditating. On the other hand, when I am supervising a new withdrawal, exercise and diet are part of the program. I teach meditation but it is not so popular. Acupuncture is surprisingly helpful. I have not found that there is a particular association between prior traumatic life experiences and difficulty with withdrawal. The major issue seems to be duration of cumulative exposure to SSRIs and therapy. It is possible that the drug has reduced frustration tolerance and coping skills and leaves the person more vulnerable to stress. This could use more exploration.

*I disagree with you about benzodiazepine withdrawal frequently being protracted. I write about this in more detail in ‘Xanax Withdrawal.’ Again, I need to emphasize that the use of Xanax is reserved for the most serious situations. The case I describe is not an extreme exception.

*In my experience Neurontin has not been of much benefit except for its sedative properties.

Report comment

How can you disagree about benzodiazepine withrawal frequently being protracted? There are thousands of us LIVING IT. The charities in the UK flooded with people coming off BOTH benzos and SSRIs and becoming protracted. I am one of them. The study done by the Cochrane foundation found that benzo w/d and SSRI w/d only differ in a handful of symptoms but are otherwise one in the same and to call one “dependency” and not the other is foolish. Perhaps since your focus is on SSRI folks, you are biased, but that doesn’t make your opinion fact.

Report comment

I’d also ask some questions:

– do people who get akathisia have a history of using anti-psychotics such as Zyprexa? I did develop restless leg syndrome, which is akin to akathisia in some aspects after Zyprexa and Seroquel (both only short term use) which persisted over a year after stopping all the meds and kept returning periodically for some time after that. What helped was iron supplementation (magnesium supplements helped but only with immediate symptoms – e.g. taken just before sleep).

– are you able to recognise symptoms of anterograde amnesia in patients treated with benzodiazepines?

Report comment

Dr. Shipko, first and foremost, Thank You for rendering some of your services online for free.

In your post you mentioned that reinstatement can be harmful. Any elaboration on that particular area would be greatly appreciated by myself and the masses alike.

Report comment

Mr. Lewis, if every household in America had a bottle of Xanax in the medicine cabinet Anheuser-Busch, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer and your local neighborhood drug dealers would be out of business in no time. The biggest problem with benzodiazepines is their affordability, dependability, reliability and low side a/effect profile. Their great for treating a broad spectrum of so called “disorder’s” and that’s just plain “bad for business” for the big drug companies who want to push their newest, novel garbage. And it’s counter productive to the pharmacologist’s looking to use human populations in their “control group” for the advancement of the concept of Bio-Psychiatry as a whole. There are no “good” and “Bad” drug’s. Just good and bad relationships with the drugs. There’s no such thing as Bi-polar 1&2, MDD, ADHD, SAD (that one’s the funniest!), etc. There’s only psychological and neurological diversity in the human species. I’ve smoked/snorted the finest blow. Shot the best dope. Drank top-shelf booze. And I’ve never had a problem stopping the aforementioned D & A as I have with Effexor XR. Do you want to know why that is? It’s because the drug’s are conspiratorially formulated to give to the consumer the very symptom’s/ailment’s that it (the new brand-named drug) claims to treat/prevent in the first place. Remember the Cold War? Now were in a race with the Russian’s to construct the first fully functioning Manchurian Candidate. Dude, my Old Man is an ex Marine turned electronics warfare technician. He’s got a Secret-Level security clearance from the DOD. I’ve had the fortune of meeting some pretty cool science guy’s during my 36 years of life. One was a Biochemist that specialized in neurochemical warfare agent’s. He told me to avoid antidepressant’s as they are a form of brain surgery at the chemical level. And suggested that I stick with the quick-fix, feel-good-fast drug’s like Xanax, Valium, Nembutal, etc. WOW!!! I sure do wish I would’ve listened to that man, 14 years ago. He said something else (back then) that I will never forget: The 2 most valuable side effect’s of any drug are Suicide, and Homicide, for the CIA/NSA psychological black-op’s program. And the test subject’s are no longer restricted to death-row prisoner’s as that environment doesn’t provide adequate genetic diversity. But rather the very last place on Planet Earth that anyone would ever suspect; The very office of the physician (M.D.) that swore to the Hippocratic oath to never intentionally harm a patient and or compromise a patient’s well being for financial gain and or experimental result’s. Benzo’s are essential. Like Aspirin. They need to be made available to the public-OTC. Especially in liquor store’s, as a safer alternative to ethanol. And or to mitigate consumption of either one or both substances. And to keep people out of the growing psycho/penal system. And doctor’s office’s in general. Wouldn’t you agree? And if you don’t, then please explain to me how having ten’s to hundred’s of milligram’s of “disorder” drug’s in your system for day’s, week’s, month’s, year’s at a time is supposed to be more neurologically nutritious than just getting high on only a fraction of a milligram of Xanax, sporadically? Maybe it’s time to move on. Just maybe Psychiatry need’s to be dis/regarded as an antiquated, inadequate, less-competent approach to mental health. And what is this MPH (master’s of public health) nonsense? That sound’s kind of “Third Reich” to me. Don’t we live in a time where Gay’s, Jew’s, Black’s and Gypsies have a right to live free and be happy too? Why doesn’t the same apply to bipolar’s, schizo’s, manic depressives and anxious people? I don’t care if I meet the criteria of an official psychiatric diagnosis like bipolar 1234, blah, blah, blah, blah. I said I liked Percocet and Valium. It get’s me high. It makes me feel good. It keep’s me going. So what’s the problem? If you don’t like a certain drug don’t take it. But don’t tell me not to take a certain drug, after I told you what works and what I like. Catch my drift? It’s like I told my shrink the other day, I said, “your opinion is of no concern to me. When you can balance a simple redox equation then, you can tell me what kind of chemical to and to not ingest.” Well anyway, I hope you got something out of my tirade. Sorry if I came off as a bit rude. But I really do believe that a majority of physicians are grossly uneducated in chemistry. For example – Zyprexa is a benzodiazepine that’s just been denatured with poisonous sulfur so as to minimize the pleasurable (full agonistic response) effects. It has some unknown effect. But normal people don’t like it. So the cult of pharmacology slaps a label on it – “Antipsychotic.” What kind of sense does that make? Until next time, think outside the bun/dsm my friend…….

Report comment

Chemonster1980

You said: “Mr. Lewis, if every household in America had a bottle of Xanax in the medicine cabinet Anheuser-Busch, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer and your local neighborhood drug dealers would be out of business in no time.”

I would say that close to 100 million prescriptions of benzos written yearly in the U.S. has not reduced or replaced other drug consumption; if anything it has only increased other drug use, perhaps even including SSRI’s.

And benzos have clearly become the drug of choice for opiate addicted or dependent people to add to their ever so deadly drug cocktail. At least 30% of all fatal overdoses involve the DECISIVE deadly benzo component. Unfortunately, I think we can predict what might be in Prince’s toxic drug screen.

I empathize with your anger and cynicism regarding the devastating effects of SSRI’s on unsuspecting victims. But let’s not minimize the dangers and damage done by other categories of drugs, especially benzos. The tens of thousands of people seeking help (outside the medical establishment) on multiple websites dedicated to major problems with benzodiazepines is testimony to the scope of this problem.

Respectfully, Richard

Report comment

I agree with you on that 100%. Everyone (the majority) that I know who have or had an Rx for an opiate pain medicine want’s to use benzo’s (Xanax especially) with their opioid RX to get “higher.” And then they reach a point of complete dissatisfaction with their current prescriber, wind up in methadone maintenance with an ever escalating dose of methadone. And eventually that’s not enough. So back to the opioids and benzo’s, along with the methadone. Or in some cases, street heroin that’s not really heroin, but the superstrong fentanyl analogues that are measured in microgram’s. And from there, the graveyard. I cant count on my finger’s and toes the people I knew personally, that met that fate. Sad but true.

My anger and cynicism is mostly directed at myself for allowing this to happen (to me) in the first place.

I’m not antipsychiatry. I think Psychiatry is essential for the well being of peoples in mental distress. It’s up to the practitioner to be a good psychiatrist. And when Rexulti T.V. commercials come right out and admit that, “two out of every three people on an antidepressant still “SUFFER” depressive symptom’s” well, like that timeless verse that Robert Plant sung in the song Stairway to Heaven -“and it make’s you wonder -”

With biostatistics like that it make’s me wonder,

1) why are we still using the damn thing’s?

2) how could a practitioner justify psychosis and suicide, over pleasure and overdose?

And unfortunately, I don’t think we will ever know for sure what was in Robin William’s blood when he decided that life was just too much, and hung himself.

And now that my Effexor XR is no longer effective should I

a) continue down this path of suffering, hoping that with a little time and moderate Klonopin use, the sun will come out once again?

b) reinstate the same or different AD with moderate Klonopin use (for dysphoria), wait for 4-6 week’s for something. What? Who knows?

c) chamber a 15 gram, .45 caliber standard U.S. Army ball round into my Dad’s old 1911A1, stick the barrel in my mouth, pull the trigger, and hope that the Human Conscience doesn’t survive the physical death of the brain?

d) remain strong (psychologically) and try to be optimistic that my situation will better with time, even if it mean’s a little chemical indulgence here and there?

Respectfully, Dana A. Callicoat

No. I’m not female! LMFAO!

Report comment

By the way, I wasn’t completely unsuspecting. Back in 2002 when my doctor handed me a month or two worth of Effexor XR free samples he said, “and none of this stuff is addictive.” I kind of knew right then(intuitionally) that that was too good to be true. I mean, what kind of drug makes you feel better without making you feel good? LOL!

Also, I noticed a difference almost immediately after my first dose. I felt better than ever, for no discernible reason. Maybe that’s because venlafaxine is much like Cocaine in that it affects the three NT’s that are thought “theoretically” to be complicit in depression, anxiety, etc.

And how is it cynical to be angered about the devastating a/effect’s of SSRI’s. I don’t feel I’m cynical at all. I’m innocent. Had I been offered Xanax as a first-line treatment for transitory anxiety, would I be in this scrape that I’m in now. Alcohol (ethanol/ethyl alcohol) kills one hundred thousand people annually. But what about the ten-plus million or so people that rely on it everyday, just to get to the next one. What about the good hard working folk that make a case of beer last a week? Are you suggesting they have behavioral defect’s that put them at risk for suicide, depression, racing thought’s, and so on? Do you want to make patient’s out of that group of people?

Last night I consulted a prominent European chemical scientist as to why the medical establishment would treat me this way. here’s a brief excerpt of our chat – “Therapeutic intervention targeted on the monoamine and opioid pathways will potentially enrich the quality of life of even the nominally “well”, not least because – by the enlightened standards of posterity – we may all be reckoned mentally ill.”

Pretty scary, isn’t it ?

Any comment’s on that ?

Dana A. Callicoat, Respectfully!

Report comment

Chemonster1980

You said : ” I think Psychiatry is essential for the well being of peoples in mental distress. It’s up to the practitioner to be a good psychiatrist.”

Perhaps your faith and belief in the necessity of Psychiatry for people suffering with some form of mental distress has been part of yours and millions of others’ undoing. Making a “break” from that way of thinking (or expecting them to solve these problems) might be an important step for all those seeking some type of path to recovery.

These are NOT “diseases” that need to be drugged away, which is the primary outlook and approach of Biological Psychiatry. These (eg. depression and anxiety etc.) are better viewed as coping mechanisms that are usually functional and successful in the short term but sometimes get stuck in the “on” position and become dysfunctional, self-defeating, and socially unacceptable over the long term. Drugs (over the long haul) make things worse and more chronic due to the brain’s compensatory reaction to the drugs.

I believe in the neuroplasticity of the brain and the value of finding some form and/or plan of micro-tapering for a protracted form of slow withdrawal from the damaging effects of psychiatric drugs. There are many success stories reported here on MIA and great resources detailing helpful strategies on the website like “Beyond Meds” run by Monica Cassani.

We cannot underestimate the value of social supports such as close friends and family, and especially other people going through the same process of withdrawal. Therefore, websites such as Benzo Buddies and Surviving antidepressants that offer support and advice for coming off these drugs can be life saving and essential lifelines in this struggle.

Yes, having a supportive and knowledgeable doctor or psychiatrist can be very helpful in this process, especially to obtain the appropriate prescriptions for the drugs necessary for micro-tapering. But unless they are a proven expert in psych drug withdrawal their approach may be no more helpful than advice you could receive within one of these internet forums from “citizen scientists” who have accumulated their knowledge for self survival purposes.

Everyone must find their own path to recovery. Gather as much information from all sources, including your doctor, and make your own determination for how to proceed with your withdrawal at your own pace while staying connected to your support system. If one must remain on some level of drugs to maintain themselves, so be it, but people can reevaluate that decision on a periodic basis.

Don’t be so hard on yourself. There are bigger forces at work here that are responsible for the psych drug crisis that is effecting millions of people. I admire your perseverance and resilience in this battle.

All the best, Richard

Report comment

Instead of prescribing benzos you might consider how histamine intolerance and mast cell dysregulation are involved.

Benzos and other psych drugs often act as anti-histamines and that is actually what is feeling helpful for a good number of folks when they take those drugs. When one uses plants (diet and supplementation) to help regulate histamine instead of pharmaceuticals we start to see a deep healing process occur.

Benzos might in fact relieve discomfort in the present, but they’re still operating on the principle suppression. Plants seem to heal…and often aren’t needed daily and in fact some folks find rotation to be really important in order to avoid developing sensitivities. Daily use of drugs almost always becomes highly problematic. In the hyper-sensitized folks it remains simply dangerous quite often.

I wrote about the histamine issue recently. We’re finding more and more people discovering this to be significant for them in withdrawal groups.

this one is recent:

Have you considered histamine intolerance associated with psych drug use and withdrawal? http://wp.me/p5nnb-b8I

Here are a couple of others written from early on in the process of discovery that others have also found helpful.

The histamine intolerance link and how this paleo girl went vegetarian (even vegan, for the time being) http://wp.me/p5nnb-8Dj

Histamine Intolerance: can be associated with folks getting psychiatric diagnosis http://wp.me/p5nnb-9tW

finding non-pharmaceutical solutions seems to be critical for long lasting and profound healing…crisis intervention with pharma may indeed, on occasion be helpful, but in the long run some of the plants used can really bring about change in a way the pharmaceutical solution simply will not.

Research:

Nigella Sativa (black seed and black seed oil)

Holy Basil

Olive leaf

Stingy Nettle

Black Cohosh

White peony root

(the list goes on…rotation with more than one plant seems to help a lot for some folks…others can take things more regularly…the risk of hypersensitivity is always there…some folks don’t tolerate even these gentle plants at first but as they heal can add them very successfully…)

plants can be very potent and simply not nasty in the ways that pharmaceuticals with anti-histamine properties are…and yes, that includes benzos and SSRIs (and neuroleptics for that matter too)

it’s a good idea to look at histamine, methylation, etc in those coming off psych meds. It’s starting to look like most folks are impacted in some way or another.

Report comment

Dr. Shipko, Thank you for another informative article. However, one brief comment.

You state: “I have been profoundly influenced by a patient I saw who had a state of tardive akathisia that was so intolerable that they were extremely suicidal. Valium was prescribed and when the dose got up to 90 mg of Valium they calmed down and suicidal thoughts stopped. Two weeks later, out of concern about the high dose of Valium, I reduced it to 60 mg, and the akathisia came back and the patient committed suicide. The patients with tardive akathisia are pretty much all suicidal to various degrees, and the benefits of benzodiazepines need to be considered in certain patients.”

How do you know that you’re not making the same mistake that Psychiatry makes when they blame the “underlying condition” when the condition might actually withdrawal? Here, in your defense of using benzodiazepines, when you say that when you reduced the benzo from 90mg to 60mg “the akathisia came back”. That could very well be the case, if you’re assuming that the benzo was “covering” the akathisia from the SSRI. However, benzodiazepines, when the patient has been on them for any length of time over a month or so, ALSO cause severe withdrawal syndromes and delayed withdrawal syndromes (I know, I’m living it) and I think you’re overlooking the fact that you REDUCED THIS PERSON BY 30 MILLIGRAMS OF VALIUM in one go!! You cannot do that to someone who is dependent on benzos and not expect a severe withdrawal reaction.

There are people starting out on 80mg of Valium (or 4mg of Klonopin) when they begin their tapers and they DO NOT EVER drop by 30mg equivalent of Valium. They remove perhaps 5-7% of their current dose over a month’s time to keep from deteriorating into severe withdrawal but a 30mg drop from 90mg is a 33%+ drop and would be intolerable to almost anyone who is dependent on benzos.

I have had SEVERE akathisia and also the delayed withdrawal syndrome from benzos myself (it took 4 months post cold-turkey for it to “kick in”). I do understand that sometimes there are severe cases where suicide is a risk and the patients need relief and reinstatement of the SSRI fails, so you choose benzos to give them the relief they need to not take their life. However, if you’re going to use them in these cases, you need to apply the SAME conservative method of tapering to those as you would to SSRIs and not drop someone by 33%+ when you “become concerned about the high doses” you put them on.

Just my 2 cents.

Report comment

Mistake correction: Should read “How do you know that you’re not making the same mistake that Psychiatry makes when they blame the “underlying condition” when the condition might actually BE withdrawal?”

Report comment

I agree with elocin. The first thing I thought when I read the cut in Valium by 30 mg was that was the culprit.

And my husband survived 20 months of extreme akathisia from an amino acid detox(basically cold turkey) off Ativan. He only survived it with 24 hour loving support from his family, though. I just wanted to give hope to those who may read this and feel discouraged about the “sometimes” part of recovery.His akathisia was from a benzo, but, really it’s all the same thing, being HPA axis suppression recovery. So, the recovery is just as hopeful. He never ingested any other psychoactive substance (including caffeine) and did as much as possible to promote a return to homeostasis by reducing stress, eating well, etc. He’s close to 100% recovered, and fully recovered from the akathisia.

I realize that a physician’s point-of-view is different and the responsibility that comes with helping people off these drugs is immense, so this article is actually mind-blowing to me, coming from a practicing psychiatrist who has obviously done his homework. Bravo to you, Dr. Shipko, you’re a rare breed!

But, I do think that what elocin has said is crucial in gaining further understanding and truly helpful strategies in dealing with the suffering of akathisia. If we were forced to do it again (ha, never in a million years!), we would microtaper and have always wished that we knew about re-instating properly before it was too late. We didn’t have the luxury of that information at the time, 5 years ago. The community knowledge is growing and it’s people like Stuart Shipko, who are willing to listen to survivors and make needed changes, that will carry this beyond the Survival stage and into the Victory stage of no more senseless suffering.

Report comment

Kathy I’m so sorry to hear of your husbands terrible suffering but am so glad he is better.

I just wondered, was there anything specific he did to recover or was it a question of waiting it out?

I have been suffering from severe akathisia for 10 months and am going out of my mind. I don’t get any relief. I got mine on the med (citalopram) very soon after starting it and it’s never gone away. I was on it longer than I should have been (8 weeks) then put on other drugs, which I came off earlier this year as they worsened my akathisia. I now have severe withdrawal syndrome as well as severe akathisia. I try to function but can’t. I just wondered whether there was anything specific that helped or if time is the best healer? Thank you.

Report comment

The 90 mg dose of Valium was established over a two week period of time. Dropping it to 60 mg at two weeks would typically be a pretty safe dosage change, and is not analogous to tapering from 90 mg after a longer period of time. Could the Valium itself be the cause of the suicide? No way to know, however, they were profoundly suicidal with a constant sitter prior to the 90 mg, and committed suicide within 24 hours of the dose change. My opinion is that it was my desire to avoid complications from the Valium that was the primary problem.

Report comment

“Let us hope that public opinion trends further away from SSRIs and the unproven benefits from psychiatric drugs in general and that research will be done to clarify just what these drugs are doing and what can be done about the adverse effects.”

I find it rephrensible that almost no research has been done to identify the harms of psychiatric drugs, and of course when such harms are found (as they often are) serendipitously in studies and resarch, they either gloss over it or falsely attribute it to “the illness.”

It’s reckless to the extreme. As soon as they knew that the drugs caused harms, any conscientious profession would at the very least go to great lengths to best understand those harms, if not feel compelled to quit using the drugs altogether.

Instead they realize the harm they are doing and just try to cover it up. Meanwhile millions of people go on suffering the effects of drug induced brain damage, which absolutely no hope that a real treatment or cure for their tardive dyskinesia, akathisia, drug induced OCD, etc will ever be found in their lifetime because the people who control the research are the people who did it to them in the first place and are too busy trying to cover their own asses.

Report comment

You think more people experience protracted wd from ssri’s than benzos? Seriously? Have you checked out the internet support groups? There are around 15, maybe more, support groups for benzos sufferers but maybe a couple for ssri’s. There are at least three Facebook support groups JUST for protracted benzos wd. In my lengthy experience in many different psych drug support groups benzos sufferers outnumber the ssri sufferers like 5o times as much.

Report comment

Dr. Shipko, may I ask how you were able to see and acknowledge the harm done by anti-depressants? Sincerely I want to know, what turned the light on for you? I am interested to know that because if that small opening in your belief system was there, allowing new information in, I’m hoping it will be the same avenue of entry to allow you to see and acknowledge the harm done by benzodiazepines if you will only open yourself to it.

Last year I invited you to visit Benzobuddies.org and read. Did you ever do that? It would be better to join the forum, (probably anonymously) because then you have access to the protracted portion of the forum which is hidden from public view.

How on earth do we get you to hear us?

Report comment

The “light” on SSRI antidepressants was shed in the mid 90’s. I had a website on panic disorder that was very popular called ‘The Panic Disorders Institute.” Around that time the SSRIs came out and were promoted heavily for panic disorder. I saw a lot of patients who were prescribed SSRIs for panic disorder who then had the most severe panic attacks ever. Doctors were telling them that ‘this can’t happen.’ When people realized that I acknowledged that it does happen, I was flooded with hundreds of people c from all over the country who had all sorts of adverse effects of SSRIs. They couldn’t find a doctor who would even listen to their story. Of course, I had no treatments – I hadn’t even heard of most of what people were complaining about. But patients couldn’t (and to this day still have a problem with this) find a doctor willing to acknowledge that the adverse symptoms that started after initiating the drugs were likely side effects. I trained a long time ago, back when if you started a new drug and then had a new symptom, it was a side effect – whether or not the doctor had ever heard of it before.

About the BDZs. I have much more experience helping people to stop taking BDZs than I do with the SSRIs. I have read benzobuddies, thank you, as well as other BDZ boards for years. In Xanax Withdrawal http://xanaxwithdrawalbook.com/ I address the issue of protracted BDZ withdrawal and explain my reasoning and opinions.

I’m OK with people disagreeing with me, and I am not going to defend my clinical experience and understanding here. Read Xanax Withdrawal and then write me a private email and we can dialogue.

I realized that even writing about using the BDZs for tardive akathisia would rub some people the wrong way, but these drugs can be very helpful and for many the benefits outweigh the risks.

Report comment

Reading your book doesn’t really help people, like myself, who are already in protracted benzodiazepine withdrawal. I do realize that, like the SSRIs, had most people who were on benzos tapered properly from the beginning, then they wouldn’t experience the more severe and protracted withdrawal syndrome. However, the problem is the same: if you don’t find the information in time and your doctor cold-turkeyed or over-rapidly tapered you, which most of them do out of ignorance–and then months down the line you feel like you can’t take it anymore once the delayed w/d sydrome (or tardive akathisia as you call it) kicks in, reinstating the benzo (just the same as the SSRIs) DOESN’T ALWAYS work. And then, you might find yourself back on the benzo either 1. worse 2. no better or only mildly better and then having to find a way off again — which can lead to kindling and even worse outcomes in the end, in my own personal experience.

Report comment

I have a friend who was given Xanax to help ease her terrible Paxil withdrawal. Now she’s suffering terrible Xanax withdrawal as well.

Report comment

Going to the crack dealer for a different form of crack, yeah that’s gonna work.

Report comment

I share all of your concerns about the benzo use…while I’ve seen enough SSRI withdrawal to not for a second think it’s potentially any less nasty than benzos (which is another common misunderstanding) — this other extreme of using benzos to come off SSRIs is a highly problematic and potentially dangerous thing…which is why I wrote my first comment above…

I’ve always said that pretty much anything can go for any given individual to get through the dark night which is withdrawal…I’m not opposed to very carefully using (generally micro doses) of drugs when necessary. The thing is most MDs will over-use this both in how often and how much (most doctors have no experience whatsoever in the use of micro-doses and don’t know anything about how powerfully helpful it can be) MDs are trained to prescribe and too often it’s simply their default for lack of knowing what else to do.

In any case there is a difference between very rarely and lightly using drugs to come off drugs and speaking about it in general terms. Part of the problem, too, is the folks we see on the boards, benzo and otherwise, are not representative of who MDs see in their offices…not in terms of the full spectrum. We see more people who are severe on the boards in a few weeks than most MDs gets a chance to see in a lifetime…so everyone needs to be careful about generalizing. Some of us have exposure to many more of those who have been gravely harmed than others.

Not everyone is harmed in this process and that’s hard for those of us who see 100s of those harmed to remember too.

Report comment

On a related noted, a plug for the Surviving Antidepressants Website:

One of the goals of http://SurvivingAntidepressants.org is to collect long-term longitudinal case histories of tapering and withdrawal syndrome and more than 1,200 can be found here http://survivingantidepressants.org/index.php?/forum/3-introductions-and-updates/. Essentially, the more people who post their stories on this site, the better position we are to provide more information to folks like Dr. Shipko that will encourage them to continue to evolve in their views regarding withdrawal and maybe not treat us as those rare obscure cases.

Report comment

Sorry for my bad grammar. Unfortunately, I can’t correct anything as this site doesn’t provide opportunities to edit posts.

Report comment

This article is interesting to me because my SSRIs and Neuroleptics caused severe and debilitating tardive akathisia. I was seeing my psychiatrist once a month for Med Checks and he never noticed my body jerking, profound sweating and constant moving in the chair. It took an independent neurologist to see it and this doctor actually screamed at me that I had the worse akathisia he’d seen in 40 years and the psychiatrist drugs were killing me. This was my wake up call because I had no idea why I felt this way, constant pacing all night, feeling like I was coming out of my skin and when I would tell my pdoc about it he said I was anxious. My pdoc kept trying to tell me the neurologist was wrong and when it was akathisia from toxic drugs””’

I had been prescribed up to ten 1 mg of Xanax a day for “my nervousness” which was profound the akathisia and toxic reactions form the psych drugs. On my own I tapered off numerous psychiatric drugs including 2 kinds of benzos and now years of being drug free have found myself. It was a difficult journey and I was basically house bound for 2 years in withdrawal hell. My body and mind slowly gained ground and being able to lay down quietly without jerking and having muscle spasms is heavenly.

“If I’d only known the road I went through with psychiatry and psychiatric drugs would lead me through hell and back”.

Report comment

I need to add my sleep cycle never adjusted and I have awful insomnia. The leftover effect from psychiatric drugs.

Report comment

Congratulations on being able to taper off all those drugs Aria. Man…ten mg of Xanax for anxiety. That just sounds overtly abusive. I work with a number of people who are coming off and I see the absolute hell people go through. And having a doctor discount your akathisia as “nervousness” is simply malpractice. So sorry you had to go through that.

Any tips for those who are going through a similar process? What helped you the most?

Report comment

My goal was to be completely psych drug free and I always kept this in mind. I didn’t know any better so I tapered off two or more drugs at a time. After reading on several forums how to carefully taper I realize I did it way way too quickly. There was no support from any physicians or therapists, all on my own. Because I’d gotten so obese on the drugs I lost 80 pounds in a matter of months. To now not have drug induced panic, scarey thoughts, muscle spasms, incontinence and indescribable Akathisia was a blessing.

To see my family and friends realize OMG is the old Aria back?? The Aria before the psychiatric drugs?? When my long time friend simply said, “Welcome back”. That said it all.

A side note is the psychiatrist I saw for all this time had no clue of what he was prescribing and after I read his office notes (yep, I got them) this fact was even more evident.

Report comment

Congrats…great story.

Report comment

http://retractionwatch.com/2012/03/19/author-retracts-paper-claiming-antidepressants-prevent-suicide/

I wonder how many people will realise that this study was retracted…

Report comment

for those who need hope about the possibility of healing:

Today on Beyond Meds is the first of the IT GETS BETTER series:

The “It gets better” collection will be a series of republished posts from when I was gravely ill from the psych drug withdrawal process and the following protracted psychiatric drug withdrawal syndrome. So many folks out there are now going through the heinous process of finding their way through psychiatric drug withdrawal syndrome and other iatrogenic injuries from psychiatric drugging.

While many find their way through after weeks or months, for others it can take years to really get out of the deep disability and darkness it creates. I’m going to start reposting my personal pieces from those difficult days, so that people can see how far I’ve come and find hope that they too might come out of that darkness and find some peace and joy again. I know it’s possible from my own experience and from the many who have found healing and wellness again on this journey ahead of me and with me.

During these times I was unable to sit upright in bed. I was only able to walk to the bathroom and rarely to the kitchen. My muscles became totally atrophied. I was too weak to hold a toothbrush up to my mouth and therefore went a couple of years without doing what most people consider simple acts of hygiene. I wrote with the laptop propped on my knees and my head propped up a bit with a pillow. Writing was a lifeline that helped me continue. It’s been a source of great joy to find out that my keeping this blog has helped so many others.

This is not my reality anymore. I am up and out of bed. I practice yoga daily. I dance, I walk and I cook and run errands and do chores. I have not achieved perfect functioning. I still can’t make firm commitments or travel. Still I can enjoy many things in life and I’ve developed a deep appreciation for what I’ve been through and how much it has taught me. Life is a wondrous thing and simply being alive is a reason to be grateful as far as I’m concerned.

I’ll post one a week for a while and see how it goes. Most of these were written from within a dark fog of various sorts of pain and hellish sensations. I will be leaving them largely unedited, so consider that when perhaps something is not clear.

SEE: It gets better: A Portrait of Poly Psychopharmacology

http://beyondmeds.com/2014/08/11/it-gets-better/

Report comment

I am very glad to be sharing with everyone here for the wonderful work Dr Lbezim has done in my life, for the past 2years i was diagnosed of herpes disease and ever since i have been very unhappy, until one day when i came across a shocking testimony about how Dr Lbezim cured someone of his herpes disease, without wasting much time i contacted him immediately on his email address: [email protected] and after i explain myself to him about how terrible i have been, and he assure me that he will help me to cure my herpes disease, after he has prepared the herbal medicine he sent it to me and i started using it as he directed. Within 2weeks i was totally cure, i am forever grateful to Dr LBEZIM for helping me on my herpes disease to be cured contact his email address: [email protected]

Report comment

Firstly, thank for your dedication to this topic. If you can help with me with this question, I think it would bring me great relief as your statement on tardive akathisia possibly being permanent has brought me a lot of anxiety. I have also been out of work for 3 weeks unable to function and losing too much weight and sleep. Here is a brief history: After 8 years of Paxil and a slow taper, I went down to 1.5 mg. It was brutal and took me 4 years to feel somewhat normal. About a year later I started 5mg of Celexa for constant neck pain, I stayed on 5mg for 3 years. The neck pain subsided so I tapered to 2.5 mg of Celexa then came off completely with very minor withdrawal symptoms (slight depression and irritability). At about 7 months I started to become a bit more stressed and also developed tingling/numbness in my hands and feet (late onset withdrawal). I had this for about 3 months and was growing increasing nervous about worrying about the condition. I became impatient and decided to reinstate the Celexa at a low dose of 2.5 mg. I did that for 2 days. On the third day, I said what the hell and moved to 5 mg since it was such a low dose. About 4 hours later, my body freaked out. I was up all night pacing, burning skin, spasms, intense fear, light sensitivity, no appetite, etc. I stopped the medication. The next day I was still feeling it somewhat but on the 3rd day, I was totally back to normal as if nothing happened. No physical or mental symptoms. I was fine for about a week when out of nowhere these attacks started hitting me again. I can’t explain the amount of fear and psychosis that is involved in feeling this way, it makes me feel suicidal is the only solution to my problem and that I have become permanently insane. The attacks came and went as the days passed I would have a normal day in between but the attacks were seemingly a little less intense but more frequent sometimes lasting 2 full days. I never know when one is going to hit, it takes an attack about 20 min to build up and I can feel my muscles starting to tighten. This has been happening for a month after the medication has been stopped. I should also mention I have noticed my pupils have been dilated on and off even while not having an attack. It appears I had an adverse reaction from reinstating while already being in a stressed out state. I want to know if this is the definition of tardive akathisia and if so, do the severe permanent cases come on more gradually or just out of nowhere and shut on and off like this. Also, if you hany any insight as to what might be happening I would be greatly appreciative as doctors have not been helpful.

Report comment