Chile’s Skills for Life (SFL) program, the largest school-based psychosocial intervention program in the world, has demonstrated improved behavioral and academic outcomes for elementary students identified as “at risk.” A team of Chilean and U.S. researchers assessed the SFL program and will publish their results in the October issue of the Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry (JAACAP).

The authors claim that the study is the first “to provide empirical evidence that a large-scale preventative intervention for mental health has a significant positive association with improved student behavioral and academic outcomes.”

The paper is also accompanied by a lead editorial in JAACAP by Guilherme Polanczyk from the University of Sao Paulo in Brazil. “Most interventions are small-scale programs, targeting narrow populations or goals, with obscure theories of change, no integration with families or the community, inadequate implementation, tested with poor and heterogeneous methodologic approaches, and thus limiting the chances of generalization of different settings,” Polanczyk writes. “This study serves as an exemplar for the fruitful partnerships between academic and government institutions—and across distant international borders.”

Javier Guzmán of the Universidad del Desarrollo in Chile was the national coordinator of the SFL program and is now a doctoral student at Boston University. He explains that the program was developed by a multidisciplinary team of experts after the Chilean department of education made addressing mental health a priority for schools. Beginning in 2001, SFL has been running on a national scale, primarily in elementary schools that have been labeled high risk based on factors such as average family income or maternal education levels.

The SFL program has been implemented in 1,637 primary schools throughout Chile and 98% of these schools were included in the study. Within participating schools, all first-grade students are screened using parent and teacher surveys, and students whose scores indicate psychosocial risk are referred to SFL workshops that begin in second grade. The workshops consist of 15 sessions; 10 with students, 3 with parents, and 2 with the teacher. The student sessions consist of groups of 6-10 students and are led by a psychologist for 1.5-2 hours. The courses are modeled on cognitive-behavioral therapy and are designed to utilize discussions and physical activities that encourage self-esteem and concepts such as respect for self and others, autonomy, and honesty. These students are then posttested in third grade.

Guzmán and his team found that of the children deemed at risk in first grade and placed in SFL programs “there was a significant positive association between the number of workshop sessions in which the student participated and the magnitude of improvements in both teacher and parent-rated behavior.” In addition, the program was found to have a significant impact on school-related measures, such as end of year promotion and attendance, which “speaks directly to the relevance of the intervention- and mental health- to academic success.”

The positive results of the study have encouraged the Chilean government to add several hundred new schools to the program for the following year. The authors conclude: “By making a national commitment to improving the educational achievement of its most vulnerable students through an innovative mental health program using comprehensive and continuing evaluation, the government of Chile has set an international standard of excellence that should inspire other countries.”

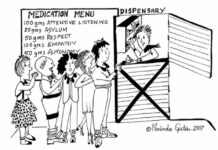

Michael Murphy, a senior author of the paper and a researcher at Massachusetts General Hospital, writes: “These findings suggest that school-based mental health programs could play an important role in achieving better educational outcomes for whole countries as well as individual children. Our findings also provide evidence that non-pharmacological interventions can be effective.”

In a podcast for JAACAP, Murphy remarks that the SFL program is unique in that it involves a partnership between the national government and the local schools. The fact that the schools must opt-in to the program may ultimately lead to greater participation from parents, a problem that has arisen in similar programs in the US.

*

Guzmán, J., Kessler, R. C., Squicciarini, A. M., George, M., Baer, L., Canenguez, K., … & Murphy, J. M. (2015). Evidence for the Effectiveness of a National School-Based Mental Health Program in Chile. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. (Abstract)

But wait, I thought these were “brain disorders” were were talking about! Do you mean teaching children skills and concepts of respect actually might improve their behavior without drugs? What a radical concept!

Good for Chile. Once again, the USA is lagging behind the curve and needs to look to South American to improve its treatment of its children.

—- Steve

Report comment

I wonder how long is it going to take until these programs are hijacked by pill-pushers though… Maybe I’m too cynical but it makes me kind of cringe.

Report comment

“At risk”, usually all that means is at risk of having a drugged childhood.

Psychiatry/psychology needs to get the heck out of schools.

“At risk” “preventative intervention” “school-based mental health programs”

Sounds real expensive. The kids would do better if the schools focused on reading and writing instead of all this expensive nonsense that makes the taxes on there house so expensive so expensive that mommy and daddy both have to work full time instead of raising them.

Its always been the liberal agenda to destroy the traditional family and replace it with government programs.

Teach my kids to read and write, I will teach them how to behave, think and protect them from things that place them “at risk” .

Report comment

Yes, psychiatry and psychology need to get the hell out of our schools.

I taught high school for fifteen years, retiring from the profession in 1988. Along with never having dealt with any student that I would label as having the spurious “diagnosis” of ADHD, we never had psychiatrists or psychologists in our schools.

Now every school, whether it’s a grammar school, middle school, or high school has at least one psychologist on staff to go around sniffing out those kids who are supposedly “ill” or verging on becoming “ill”. I really don’t know how these people can get up in the mornings and look themselves in the eye when they see themselves in the mirror. They are nothing more than shills for the drug companies and for psychiatry.

When I taught it was the teachers who listened to and walked with those kids who were having trouble in school and at home. You took this on as part of your teaching duties and as a humanitarian who cared about those who were placed in your care.

Now, teachers advise parents to drug their children into zombification so that they will no longer be bothered with the “difficult” kids in their classes. I don’t know how they live with themselves.

Report comment

Couldn’t agree with you more. It’s a truly pathetic.

Report comment

The_cat,

Neither side of the political aisle is our friend. It isn’t just the big bad liberals who are a threat.

Government abuses occur in red states also.

http://medicalkidnap.com/2015/07/11/arizona-family-terrified-foster-parents-taking-their-children-to-mexico-against-their-will/

Also, in Alaska, a young adult was snatched from his parent’s custody because the medical mafia didn’t agree with their decisions about his care. Sorry, can’t find the link but it written about on this site.

Report comment

Don’t worry , I don’t fall for the left vs right scam. No way.

Here is a good one: The Game Is Rigged: Why Americans Keep Losing to the Police State

But child drugging in schools, the left did most of that.

Debate on mental health screening in schools video

Report comment

Interesting link to the Rutherford Institute. Just wrote them to ask if they provide assistance to people being held in psych hospitals against their will since they seem to help every other person whose rights are violated.

Report comment

Psychiatry’s Views on Education

“Every child in America entering school at the age of five is insane because he comes to school with certain allegiances to our founding fathers, toward our elected officials, toward his parents, toward a belief in a supernatural being, and toward the sovereignty of this nation as a separate entity. It’s up to you as teachers to make all these sick children well – by creating the international child of the future”

Dr. Chester M. Pierce, Psychiatrist, address to the Childhood International Education Seminar, 1973

“Education does not mean teaching people to know what they do not know – it means teaching them to behave as they do not behave.”

National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) sponsored report: The Role of Schools in Mental Health

“We can therefore justifiably stress our particular point of view with regard to the proper development of the human psyche, even though our knowledge be incomplete. We must aim to make it permeate every educational activity in our national life…. We have made a useful attack upon a number of professions. The two easiest of them naturally are the teaching profession and the Church: the two most difficult are law and medicine.”

Dr. John Rawlings Rees, “Strategic Planning for Mental Health”, June 18, 1940

“The educational system should be a sieve, through which all the children of a country are passed. It is highly desirable that no child escape inspection.”

Paul Popenoe, Behavioral Eugenist and co-author: “Sterilization for Human Betterment”

Report comment

I’m glad the kids aren’t getting drugged up as much. However…I’m concerned about what “high risk” means and what these interventions actually involve. It sounds like one way or another–drugs, hospitalization, talk therapy, interventions–Mental Health, Inc. is pretty much going to get us all in line.

Report comment

Not sure how things work in Chile but let’s say a kid escapes getting drugged in the US but still gets a mental health label. That could still be quite damaging down the road.

Agree with Stephen Gilbert’s post that psychiatrists and psychologists need to get the bleep out of the schools.

Report comment

Agree, AA, and Stephen Gilbert. The key phrase in the press release is “there is evidence that non-pharmacologic can be effective”. Inherent in that statement is that drugs are the first line of “defense”. Also buried in the press release is a statement about how this will serve as an opportunity to refer children to specialists. Interestingly, just this week a young adult from Chile contacted me regarding seroquel withdrawal. This person spoke at length about the lack of drug awareness in Chile. I see this development as being very similar to the Chicago Boyz’ coup………a major human disaster.

Report comment

Y’ALL, Here is another disturbing line from the press release; “The Skills for Life program also includes two other major components – mental health promotional activities in all schools and referrals to mental health specialists for children with the most serious problems – which were not the focus of this study. ”

If I am not misreading……….what does “which” refer to; the children, the serious problems? It sounds like there was a washout of the kids considered to be most troubled. But the wording bothers me…….what was not the focus of this study? This is really seriously scary ground…..

Report comment