I remember the year my bloodtime flew out of whack. It was about a year after I started taking the drugs that psychiatrists had prescribed to me. The apartment I lived in was nestled on Boundary Street near a paper mill that smelled all over town. My landlord lived next door and shot birds that landed on his back porch to death for sport. His wife left him soon after I moved in. Then his brother moved into the apartment below mine, with his new wife who he’d chosen out of a catalog. She barely spoke English, and avoided making eye contact when I walked past to the stairs that led to my front door. I remember the way she looked when our eyes did meet. Fear doesn’t require translation.

It was a year of ruin, one in which my whole life fell apart. I earned a living delivering pizza and framing prints at a local gallery while I continued to study art at a local college. I thought it was the stress of having chosen the wrong path that led my blood cycle to become erratic. I would bleed seven days in succession, for example, and then for two sets of three to five days with spotting in between, all during a 28 day cycle. I never imagined that the psychiatric medication prescribed to me could be responsible. Instead, I clung to my prescriptions with a clenched fist. I maintained my weekly trips to see a psychologist who wasn’t much help — neither was the Harvard-trained psychiatrist he shared a practice with.

Barely able to pay my bills, I enlisted the support of social services. Then I became homeless. Enraged by my circumstances, I fell into despair, as though I had landed at the bottom of a well of grief deeper than I had ever experienced before. The shame of the diagnosis isolated me. In search of relief, I tried marijuana which my psychiatrist disapproved of. The plant’s interaction with the pharmaceutical medications he had prescribed concerned him, so I stopped soon after I began. He never cited the effects the pharmaceutical drugs themselves had on me or the ways they interacted with one another as concerns. His medical degrees from Harvard assured me of the authority of what he claimed to know.

I was a recent college graduate with a degree in Visual Art. A mentor recommended I move to New York City, but I couldn’t afford to do that making minimum wage. I told him I had painted an image of a vagina giving birth to an anatomical heart, in oil paint on paper. He said, “It’s been done before.” That was the year I stopped making art — fifteen years ago, the year my cycle broke. It wouldn’t be set right again until I stopped taking the medications I had been prescribed.

During the time my blood cycle was erratic, I lived in a state of groundlessness in the mental, emotional, and physical realms of being. Despair nearly overcame me while I alternated between homelessness and underemployment. The exhaustion I experienced, combined with surges of rage and erratic bleeding, were seen by the professionals I consulted as symptoms of physical and mental illnesses. I internalized their diagnoses and swallowed their antidotes. Their narratives became my own. The connections between losing ground in my life, the loss of regularity in my menstrual cycle and continuing to take psychiatric drugs did not become clear until I stopped taking them.

My gynecologist at the time told me I would have problems becoming pregnant. He didn’t have the insight or information to see a correlation between the psychiatric drugs and the loss of regularity of my menstrual cycle. More than a decade later, I tried to make art again. That endeavor proved to be a challenge that I could not sustain. Creating anything was difficult at best, when it was possible at all. I threw away my tools and the work I had spent a lifetime developing. I gave up on my dreams. Free flow had characterized my creative process — an art practice that had come naturally since my childhood was extinguished. Not only were my reproductive capabilities shut down on psychiatric drugs, my ability to create art had been effectively disabled.

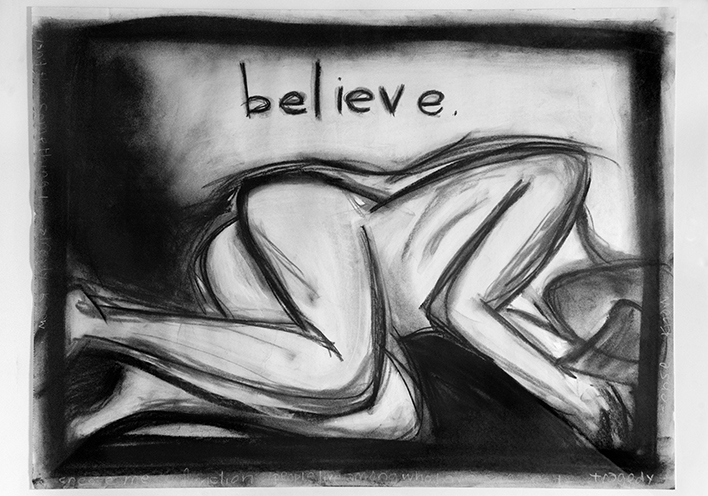

After I stopped taking the medication, in despair, I searched for a life raft. I needed to remember that I’d once done something well. So I opened a portfolio of work that I’d made before I’d given up on art. The pieces I found there had survived the devastation. I nailed a couple of my paintings up on the walls in my living room. Then I took pictures of some of them and posted the images on Facebook. That’s when another, newer mentor saw them. His feedback led me to submit them to an editor of an anthology.

When I first considered submitting my work, I was afraid it wasn’t good enough. That idea was consistent with the perpetual state of self-doubt I found myself in during my years of psychiatric drug use. Living with DSM diagnoses, and under the control that psychiatric drugs exerted, destroyed my self-confidence as well as my health. Finally off the drugs, I was able to make a different choice. I allowed the editor to decide. I submitted them, and they were published in the anthology Protectors 2: Heroes.

The work I rediscovered in my portfolio was lost and found. Finding it again in the way that I did helped connect me to the time before the drugs — a time when I made things and that process gave me life, when my blood flowed through me and my menstrual cycle was regular. It was only after my cycle returned to normal because I stopped taking the drugs that I had the courage I needed to share that work with the world. I needed the strength and stability of my blood’s cycle. Sharing my work in the anthology helped make the circle that had been broken whole again.

This morning I began to bleed. Today is the first day of a new cycle, and this time my blood is on time.

Beautifully written blog, Jyl, from the heart, and I am so sorry you also were lied to, belittled, defamed, and tortured by psychiatrists. They do like to attack the artists and women, don’t they? I love the artwork, too. I have a similar piece, from when I was drugged up. A soapstone carving of me crawling, head hidden in shame and agony behind my long locks, struggling to survive all the anticholinergic toxidrome poisonings that were forced upon me.

Shame the psychiatrists who claim to “know everything about the meds,” in actuality, don’t even know combining the antidepressants, antipsychotics, and / or benzos – today’s “gold standard cure” for “bipolar” – is nothing more than a recipe for how to make a person “mad as a hatter” via anticholinergic toxidrome.

But “Believe” is a good message. Hope is a good message. And there is hope of healing, if one gets off the psychiatric drugs. I’m glad you survived, and best wishes for the future.

Report comment

Well, the shrinks who put you and kept you on the meds didn’t know doodly. You were suffering from the tranquilizer psychosis described by a Dr. Meyer-Gross 60 years ago. Nobody believed him back then and few believe him now, save a number of alternative practitioners. Harvard may be an intellectual center of US education, but their School of Psychiatry is as thoroughly a part of the psychiatric Jurassic Epoch as the sauropods were part of the real Jurassic.

Report comment

“You were suffering from the tranquilizer psychosis described by a Dr. Meyer-Gross 60 years ago. Nobody believed him back then and few believe him now, save a number of alternative practitioners.”

I doubt that, every doctor should know the neuroleptics can cause “psychosis,” because they all have to learn about anticholinergic toxidrome in med school. Here’s the drug classes known to make people “mad as a hatter,” via anticholinergic toxidrome:

“Substances that may cause this toxidrome include the four ‘anti’s of antihistamines, antipsychotics, antidepressants, and antiparkinsonian drugs[3] as well as atropine, benztropine, datura, and scopolamine.”

And these are the central symptoms of anticholinergic intoxication syndrome: “memory loss, disorientation, incoherence, hallucinations, psychosis, delirium, hyperactivity, twitching or jerking movements, stereotypy, and seizures.”

There should not be a doctor in this land who doesn’t KNOW the antipsychotics can cause “psychosis,” via anticholinergic toxidrome.

Report comment

Thank you for your kind words. I appreciate them!

Report comment

Great writing, and even better story. The most creative time of my life was when I was pregnant with my kids and the 10 years after…then came the divorce and the drugs.

Still climbing out of that hole–I have thrown/given away hundreds of dollars of art materials, despaired of ever being able to *make stuff* ever again…your blog entry is both reminiscent and inspiring.

Thanks

Report comment

I’m still climbing out myself. Thank you for your *getting* it.

Report comment

This is very inspiring. Thank you.

Report comment

Thank *you*.

Report comment

Every day is a new day and you have proven that. The spirit shines in your work. Nicely done!

Report comment

Thank you so much!

Report comment

It was a Harvard-trained psychiatrist that almost killed me. I had know idea how psychiatry really worked and I believed the greatest lie of modern times “your serotonin level”.

That Harvard crew is scary.

Report comment

Yes, I agree! It’s ironic that an article Vivek Datta wrote and published here on MIA helped me decide to stop taking the psychiatric drugs. If I am correct he is a Harvard graduate. This is it here: http://www.madinamerica.com/2013/06/withdrawing-from-psychiatric-drugs-what-psychiatrists-dont-learn/.

It’s a relief to finally know the truth.

Report comment

Jyl, thank you so much for your story?

Would you mind saying what drugs you were on that caused your interest and passion in artwork to disappear? How long was the interest gone? I’m asking this because at 23 months off benzo drugs (was on Ativan, then was switched to Klonopin to taper), I’m still experiencing anhedonia, with no interest in former hobbies/enjoyment.

I’m very happy that you’re able to do beautiful artwork again!!

Thank you very much!

Report comment

I was on over 25 of them over a 16 year period. They belonged to all the major classes of psychiatric medication. I don’t remember what combination of drugs I was on at the time; it did include a benzo though. It took me about ten years to try and make art again. When I did begin again, it was out of desperation and a kind of necessity of the soul. A few years later, while still on the drugs, I could not continue the practice. Now, that I am off them, I have been able to start making art to some degree, again, but not in the mediums I used to work in. I hope that will come back in time though.

I am sorry to hear you’re still struggling. Give yourself time. Please be patient and compassionate with yourself. You have been through so much.

We can get through this and make it to the other side. I know we can.

Report comment

Which medications? I have trouble with breakthrough bleeding which is why I ask.

Report comment

I’m sorry, I don’t remember what combination of drugs I was on at the time. Not one doctor during the whole 16 years I took psychiatric drugs ever connected them with the “breakthrough bleeding” I experienced though.

Report comment

Jyl Ion – The first thing I noticed on MiA today was your artwork “Healing”. There is something about it that resonates with me – I can’t put my finger on it, but I sense a connection and I like the feeling. Then I read your story…

“Free flow had characterized my creative process — an art practice that had come naturally since my childhood was extinguished. Not only were my reproductive capabilities shut down on psychiatric drugs, my ability to create art had been effectively disabled.”

“Extinguish” is a powerful word, and the right word for what Psychiatry can do. I went through it too. But there will always be a spark, a smouldering ember – creativity and life-force can never be fully extinguished.

I would like to contact you privately, but I can’t find an email address. If you want to contact me, please do. My email address is [email protected]

Report comment