In a new article, Dr. Kenneth Kendler and Dr. Eric Engstrom review the historical criticisms of Emil Kraepelin’s diagnostic system published in the late 1800s. By historically contextualizing the debate surrounding psychiatric diagnosis, the authors demonstrate how modern critiques of diagnostic paradigms are connected to longstanding observations.

This review, published in the American Journal of Psychiatry, focuses on the main criticisms of Kraepelin’s paradigm that were published during his lifetime (1856-1926). Six perspectives are featured, including Adolf Meyer, Friedrich Jolly, Eugenio Tanzi, Alfred Hoche, Karl Jaspers, and Willy Hellpach.

“Questions about the quality of the empirical grounding of Kraepelin’s diagnostic system have continued to this day, Kendler and Engstrom write. “Indeed, critics have argued that a major problem with our Kraepelin-influenced DSM nosology is its excess reification.”

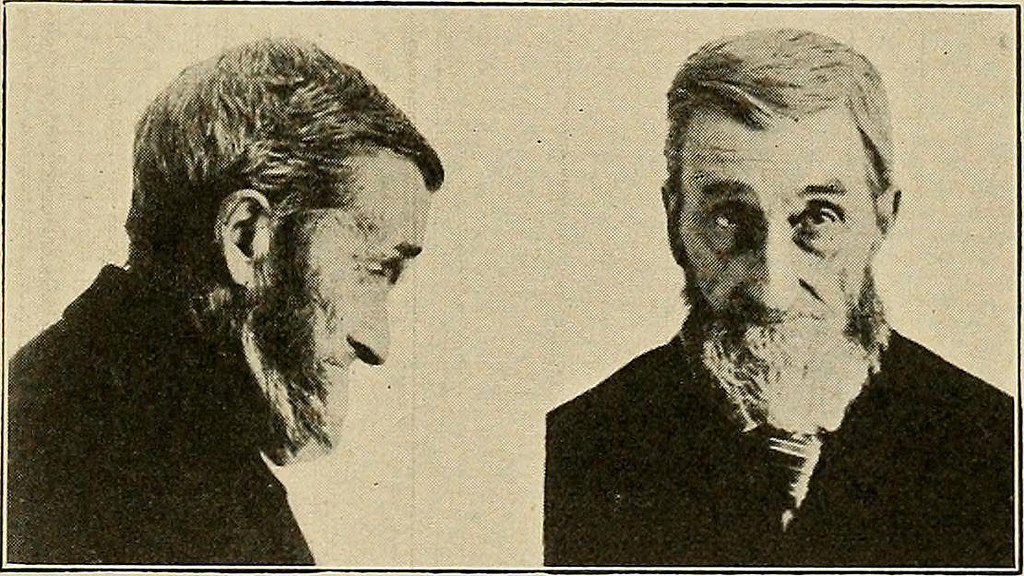

Emil Kraepelin (1896-1927) was a German psychiatrist and is widely understood to be the founder of modern-day psychiatric diagnostic systems and psychopharmacology. Kraepelin famously took the position that mental illnesses are biological entities and his diagnostic system promised that identifying a common etiology, psychological form, development, course, and outcome for each mental illness would eventually be possible.

However, Kraepelin-inspired diagnostic systems existing today, such as the DSM-5, have been met with significant criticism (see MIA report), despite their widespread use. In their article, Kendler and Engstrom depict how these six historical criticisms of Kraepelin’s nosology reverberate in our current day debates.

While some criticized the validity of Kraepelin’s procedures, clinical samples, and subsequent claims, he was most notably criticized for the gaps in his assertion that mental distress is connected to distinct diseases. Kraepelin distinguished between two primary diagnoses: “dementia praecox,” which corresponds to modern definitions of “schizophrenia,” and “manic-depressive insanity,” a definition that corresponds to today’s use of mood or affective disorders, including bipolar disorder or depression.

Adolf Meyer (1896-1927) questioned Kraepelin’s assumption that his diagnostic categories were independent of external influence. Further, he critiqued the homogeneity of these diagnostic categories and the fact that these diagnoses were defined independently from psychological systems.

Similarly, Friedrich Jolly (1896) criticized Kraepelin for his inconsistency in defining disorders. Sometimes he would emphasize course as the defining factor of dementia praecox or manic-depressive insanity, and other times he would emphasize symptoms. The diagnostic categories also came under fire for being too broad and for running the risk of overdiagnosis.

“It is not obvious why cases of melancholy that arise in climacterium should, in fact, be melancholy and not something else and why it suffices to characterize them primarily according to symptoms, whereas in other phases of life conditions that manifest an identical course should call for an entirely different interpretation.”

The authors quote Jolly: “To what extent has he created ‘diseases’ or, at least, to what extent are his diseases distinct entities from the point of view of pathology…?”

Even in responding, not all of these critics wholly discarded Kraepelin’s nosology. Some, for example, Eugenio Tanzi (1905), identified limitations and offered alternative conceptualizations to improve the clarity and accuracy of diagnostic systems. Kendler and Engstrom describe Tanzi’s position:

“Tanzi saved his strongest criticism for Kraepelin’s concept of manic-depressive insanity. Kraepelin, he wrote, contends that melancholia and mania … occur in a pure state only in a periodic form, and for the most part promiscuously—in other words, they are not two acute and distinct diseases, but constitute a single, chronic, constitutional disease, with two different aspects.”

Other critics regarded Kraepelin’s textbook as “nothing more than a passing fad,” that had successfully gained attention owing to Kraepelin’s status and skillful writing instead of any substantial empirical support. Alfred Hoche (1912) took this position. He wrote:

“Underlying all these busy efforts is the unassailable belief that even in the field of psychiatry it must be possible to discover clearly defined, pure, and uniform forms of illness. This is a belief that is carefully nourished by the analogy to physical medicine without any consideration being given to the fact that the nature of the relationships between symptom and anatomical substrate … affords no basis for any comparison between them.”

Similarly, Karl Jaspers (1913) criticized three main points that were central to Kraepelin’s nosology: (1) that the clinical observation of mental phenomena could validate the hypothesis that mental disorders are independent disease entities, (2) that common outcome are evidence of a common disease, and (3) that the “disease entity” concept could fully be established.

The authors describe Jaspers’ position:

“Citing the German philosopher Kant, Jaspers insisted that disease entities were not attainable goals but rather regulative ideas that served to orient scholarly research. He gave Kraepelin credit for recognizing that the idea of disease entities helped spawn productive lines of psychiatric research, but he warned of the danger of assuming that nosologic categories such as dementia praecox or manic-depressive insanity represented objectively true, natural entities.”

Jaspers additionally took issue with Kraepelin’s textbook because he saw it as failing to provide a coherent picture of individual patients. He referred to it as an “endless mosaic.”

Finally, upon evaluating the success of Kraepelin’s efforts, Willy Hellpach (1919) “concluded that this effort had failed to live up to expectations.” More specifically, he criticized his methods, again critiquing the focus on the course and outcome of the disease. The diverse symptoms of each case were obscured with those of any other case, becoming one indistinguishable conglomerate that offered little utility.

Kendler and Engstrom summarize this major point:

“By piling symptom upon symptom in the interest of greater subtlety and objectivity, Kraepelin had implicitly suggested that clinical evidence was more important than it actually was. Students could therefore hardly avoid the dubious conclusion that nosology was nothing more than purely “specialized fiddling” (49, p. 344) with the evidence and that, in their day-to-day practice, psychiatrists were reduced simply to diagnosing madness.”

****

Kendler, K. S., & Engstrom, E. J. (2017). Criticisms of Kraepelin’s Psychiatric Nosology: 1896–1927. American Journal of Psychiatry, appi-ajp. (Link)

It Dr. Tom Insel’s RDC, decades earlier.

““Citing the German philosopher Kant, Jaspers insisted that disease entities were not attainable goals but rather regulative ideas that served to orient scholarly research. He gave Kraepelin credit for recognizing that the idea of disease entities helped spawn productive lines of psychiatric research, but he warned of the danger of assuming that nosologic categories such as dementia praecox or manic-depressive insanity represented objectively true, natural entities.””

Report comment

Remember Les Miserables? Inspector Jalvert would have made a great shrink.

Once a thief always a thief. Once a schizophrenic always a schizophrenic.

Psychiatric diagnosis are really moral judgments. Some of these “symptoms” are bad behaviors. But by labeling the person as hopelessly depraved they are socially marginalizing them–declaring them irredeemable. Doing their best to prevent any reformation of character.

Psychiatry is not only morally bankrupt, but encourages such in our society as a whole.

Report comment

It transformed my life when I began medical school, after many years of science and arts, and learned of the concepts such as anxiety, depression, paranoia ect, that I suffered from. I also learned that, thanks to Freud, it was possible to get help, and to learn how to help others.

Luckily this was in 1952, before supposedly effective drugs began teaching physicians that mental illnesses were really due to physical causes, as Kraepelin had surmised.

When I began psychiatric residency I tried to get to know my patients and found that their traumas explained and relieved their symptoms, and this simple discovery led to a 50 year career. Part of me paid attention to the psychiatric diagnosis, but a much larger part was interested in the drama of their lives and pursuing this to the core of the problem, as science had taught me.

By total accident I also discovered that it was possible to penetrate the brick wall of thought disorder that psychotic patients suffer from.

Unfortunately I wasn’t able to penetrate the brick wall of psychiatry and psychoanalysis, to let them know of our successes.

Report comment

Too bad for a lot of people edchilde.

Report comment